The JRB Francophone and Contributing Editor Efemia Chela travels to Mozambique with Mia Couto’s novel Confessions of a Lioness.

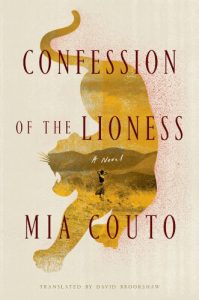

Confessions of a Lioness

Mia Couto (translated by David Brookshaw)

Harvill Secker, 2018 (originally published in English 2015)

You do not choose the book. The book chooses you. That’s why it feels easier to buy books in a bookshop. The books are better able to single you out based on your physical presence. Of course, we are now mostly homebound in the not-so-great indoors, ‘the days have gone by, dense but empty like the clouds in winter’, as Mia Couto writes, and trips to the bookshop are few and far between.

Confessions of a Lioness, translated from the Portuguese by David Brookshaw and ‘inspired by real facts and people’, found me via a Kindle ad at a time uncannily like the life on its pages. In the novel, a community is being ravaged by an unknown evil. The village of Kulumani, located on the River Lideia and surrounded by a forest, has a pride of lions hemming it in and picking off its residents (twenty-one, so far).

The book features many of Couto’s calling cards—the tight plaiting of magic with ‘reality’, real or invented African proverbs as a prefiguring of events, the very setting of Mozambique, where most of his writing takes place, and the physical and spiritual inheritances of war. It also seems very Couto-esque in a different, more indefinable way—through the hint of a feline legacy, perhaps. The author, António Emílio Leite Couto, has gone by Mia, Portugese for ‘miaow’, since childhood. In an interview with The Guardian, he said:

My parents took photos of me when I was three, sleeping and eating with the cats on the veranda. I didn’t just like cats; I thought I was a cat. Every child feels that more open borderline between themselves and other beings and creatures.

Even before the lions arrive, the residents of Kulumani live on a borderline, that between life and death. Mariamar’s three dead sisters, Silência, Uminha and Igualita, haunt her family. She is the only surviving offspring of her father, Genito Mpepe, and her mother, Hanifa Assulua. To borrow a horror movie trope, she’s the final girl.

We learn about the strangeness of life in the village from Mariamar. (For example: one of her neighbours regularly makes love to generations of departed spirits.) She is a potential victim of the lions, who only take female victims in their mouths and kill them during the night. Mariamar says of her home:

In Kulumani, all living things are trained to bite. Birds devour the sky, branches rip the clouds, rain bites the earth, the dead use their teeth to reap revenge on their fate.

Then why do the recent deaths rattle the community so much? This is one of the book’s central concerns. How do competing forms of violence shape lives? How do they transmogrify people?

Mariamar’s version of events is crosscut with the testimony of the hunter from the city who is brought into the fix the problem, Archangel Bullseye. He has his own tragic past which exists presently as a fistful of love letters and a brother sequestered in a mental institution. Archie is a sensitive man, who holds babies in his left hand because he can’t bear to hold them in the hand with which he kills. ‘Hunting is witchcraft,’ he remarks, ‘the last piece of witchcraft to be permitted by law.’

Conspiracy theories abound, not about masks and vaccines, but rather about how and why the lions descend on the village. Some believe they’ve been tempted by pigs reared for food in Kulumani, some insist they are lionesses, not lions, others simply don’t believe they exist at all. After some time spent with the villagers and their fear and the pompous administrator who wants to turn the slaying of any lions into a PR opportunity—plus cryptic whispers from Naftalinda, the administrator’s wife—Archie Bullseye posits his own theory:

And I think: Everything that we have carefully built over centuries in order to remove ourselves from our animal nature, everything that language has covered over with metaphors and euphemisms (our arms, our faces, our waists), in one instant can be converted back to its naked, brutish substance: flesh, blood, bone. The lion doesn’t just devour people. It devours our very humanity.

We speak in violence: ‘We are fighting the virus’, ‘This is a war on illness’, ‘Our bodies are being attacked’. We live in defensive rituals—elbow taps, masks, disinfectant spray, gloves, chemical warfare, sanitising every minute frontier, the metal door handle, the groceries delivered from the warehouse, the smudged phone touched, every minute. We believe the war on Covid-19 in South Africa started when we were forced to lock down in mid-March, but what about the conflicts that were ongoing before? The illnesses people were already trying to endure? We divide life into wartime and peacetime, but what if peace is an illusion, a shared dream certain classes insist is real?

Professor Srila Roy, in her work on the Naxalbari movement in India, writes about how we tend to distinguish between ‘extraordinary’ and ‘ordinary violence’ and view them as separate. Instances of revolutionary, terrorist or state-led violence are marked in history, but ordinary violence, which ‘lurks within the textures of interpersonal relationships’, is ‘subject to practices of wilful forgetting’, it is part of the everyday. This ordinary violence also enables and creates the pretext for more extreme forms of violence. Thus all violence exists on a continuum.

Confessions of a Lioness reveals that women living in a village on the edge of modernity, in a deeply patriarchal society, just a few years after the end of Mozambican Civil War, have in fact never known peace—because of their gender. Couto, whose overarching literary project is to unite contradictory worlds, interrogates the uneasy peace in the village and its latest eruption in the form of lions/lionesses with his trademark wistful and richly allegorical language. The narrative tension between the dual confessions of Mariamar, an insider, and Archangel Bullseye, an outsider, make for a pleasantly disorienting anti-detective novel, where the lines between the hunter and the hunted are mystically blurred.

- Temporary Sojourner is a series of articles by Contributing EditorEfemia Chela on fiction from around the African continent. Reading is the cheapest way to travel, after all. This is the eleventh article in the series, which draws its name from the eponymous collection of short stories, first published in 1989 and reprinted in 2011, by Editorial Advisory Panel member Tony Eprile.