“Survey confirms hunger in South Africa is escalating in the wake of the Covid-19 lockdown”, Daily Maverick

By Yul Derek Davids, Benjamin Roberts, Narnia Bohler-Muller, Ngqapheli Mchunu, Samela Mtyingizane and Carin Runciman, Maverick Citizen Op-Ed, Johannesburg, 15 October 2020

Friday 16 October is National Food Day and October has been declared the Food Security Month, but hunger has been growing under lockdown, despite the government’s commitment and efforts to help those in need. These are some of the key findings from the University of Johannesburg-Human Sciences Research Council Covid-19 Democracy Survey.

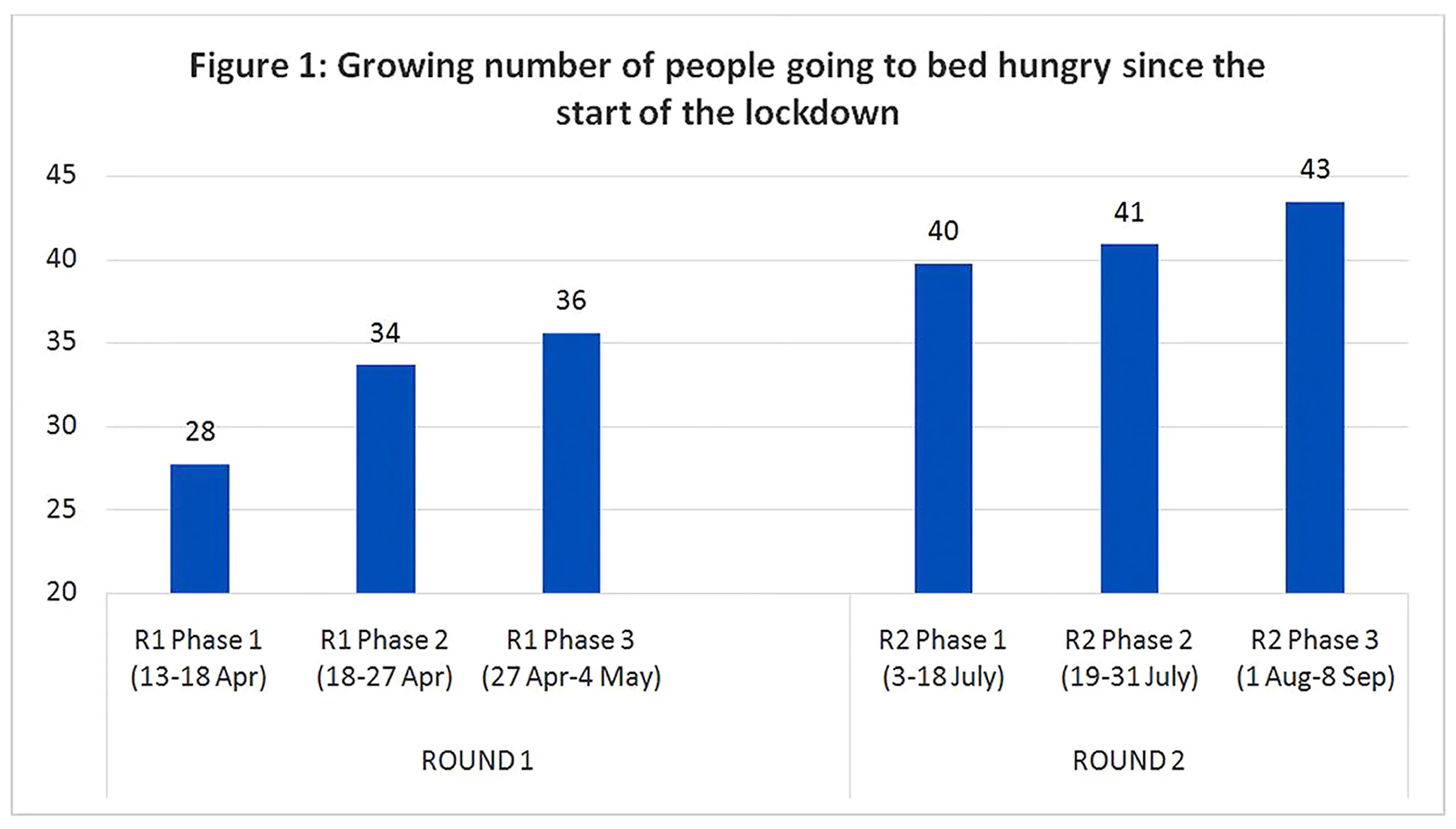

In the initial phases of the hard lockdown, in April this year, we reported that 28% of people were going to bed hungry. By July, this had grown to 40%, and between August and September increased slightly to 43% (Figure 1). This rise in hunger demonstrates the continuing economic hardship that many people are facing in the wake of the economic turmoil of the lockdown.

Overall, between April and September, the percentage of those going to bed hungry increased by 10 percentage points. There were also distinct differences between who was reporting hunger between Round 1 and 2 of the survey.

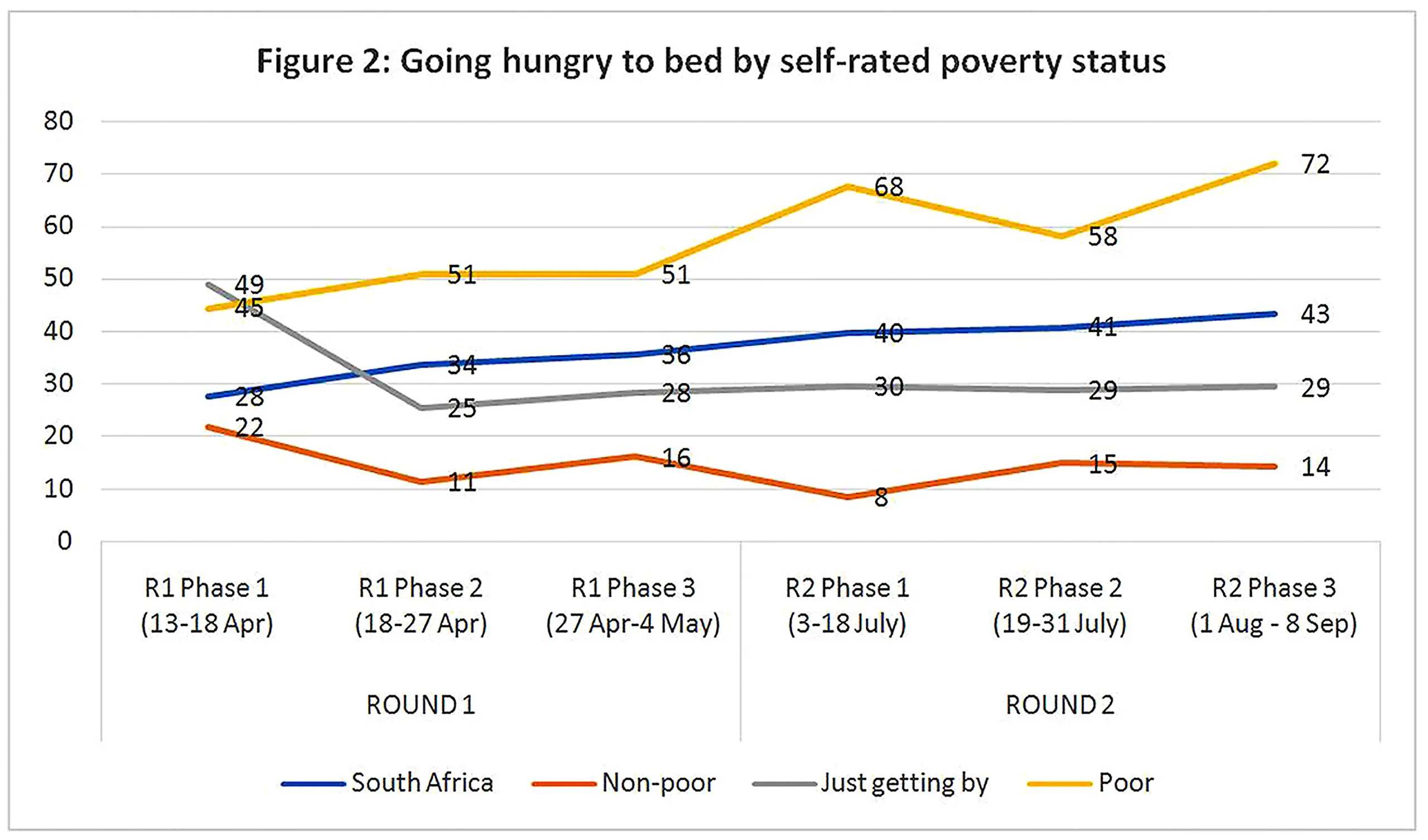

The biggest increase in experiences of hunger from Round 1 to Round 2 is among those survey respondents who indicated that they are employed part time (17%) compared with the unemployed that are looking for work (13%), employed full time (10%), self-employed (7%) and employed in casual work (5%). Big increases in hunger were also found among the participants 45 to 54 years old (16%) and 35 to 44 years old (15%) when we compare them with the 25 to 34 years old (10%) and over 55 years (1%). Figure 2 shows that the self-rated poor (14%) participants experience an increase in hunger more than those categorised as just getting by (5%) and the non-poor (2%). Those respondents earning less than R1,000 a month (14%) also experience hunger more than those who earn R1,001 to R2,500 (2%).

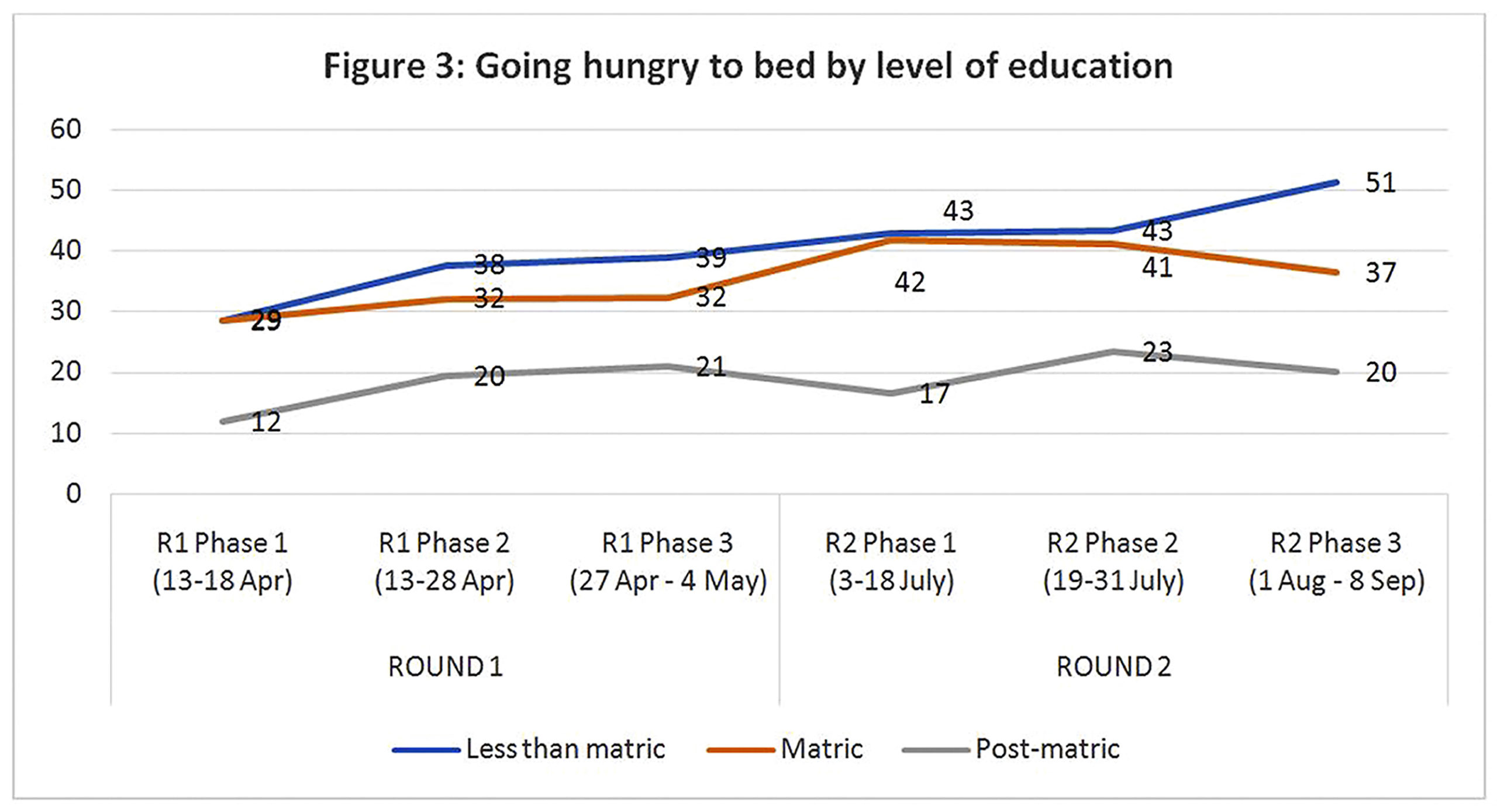

Those indicating that they have gone to bed hungry also increased, mostly among coloured (14%) respondents than black (10%), white (8%) and Indian or Asian (8%). Figure 3 demonstrates that a clear educational divide exists, with those without a matric qualification (12%) indicating a higher increase in hunger from Round 1 to Round 2 than those with matric (9%) and a post-matric qualification (4%).

This rise in hunger comes despite the government’s attempts to cushion the economic impact of lockdown. These included: an extra R250 for all social grant beneficiaries for six months, an extra R300 for those who receive child support grants in May, and an extra R500 thereafter from June to October. In addition, a R350 social relief of distress grant for unemployed citizens who are not receiving any other form of social grants or UIF payments will be provided to citizens for six months, commencing in May, ending in October.

However, a review of the Auditor-General’s report on Covid-19-related expenditure showed that some of the interventions by the government have fallen short. The report enlisted several transactions as red flags that needed further investigation. The report further states that the distribution of food parcels became more expensive, and prone to corruption and fraud, than it should have been, due to Sassa’s decision to use services of service providers instead of calling on non-profit organisations that were already involved in such initiatives. Corruption Watch also indicated that many accessible communities across the country have not received the necessary help because corruption and greed have hindered the distribution of food.

The concerns about hunger were also observed in responses to an open-ended question in our Covid-19 Democracy Survey: “For you, personally, what is the worst thing about the lockdown?”

A young 18- to 24-year-old black man from Limpopo indicated that the worst thing for him was the “shortage of food. Corruption related to the food parcels has resulted in a very bad way in my life.”

A Indian woman older than 55 from Gauteng said: “There is still corruption manifesting itself at its worst in levels of government. Stealing food parcels, ignoring the local context in Covid responses.”

Hunger is not new in South Africa. In 2017, about 6.8 million people experienced hunger, despite the fact that the right to access food is a constitutional right. More now than ever there is a need to evaluate the effectiveness of the current strategies and interventions to address hunger.

For instance, numerous appeals have been made over the past two decades to the South African government to support a basic income grant/guarantee for poor, unemployed citizens. Our previous findings demonstrate that there is widespread support for such an intervention, suggesting that the call by the C19 People’s Coalition to extend the social relief of distress grant beyond October would be popularly supported. Similarly, a group of more than 80 civil society organisations, including Cosatu and Saftu, have demanded that the government “extend the period ofsocioeconomic relief to the poor”. Supporting the 80 civil society organisations, the Nedlac community constituency has requested to meet with President Cyril Ramaphosa to discuss this looming humanitarian crisis.

Our findings indicate that without continuing support from government, it is likely that hunger will continue to grow, especially as unemployment may continue to rise from the 2.2 million jobs believed to have been lost in 2020. In addition, the emerging health and socioeconomic consequences of what is being called “long Covid” have not been accounted for and may compound the challenges we face. The findings highlight that certain sociodemographic groups are more disadvantaged than others and interventions that target the young and unemployed are needed most as we face an uncertain future. DM/MC

Yul Derek Davids is a Chief Research Specialist in the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division at the HSRC. Benjamin Roberts is a Research Director and Coordinator of the South African Social Attitudes Survey in the DCES research division at the HSRC. Narnia Bohler-Muller is Divisional Executive in the DCES research division at the HSRC and adjunct Professor of Law, University of Fort Hare. Ngqapheli Mchunu is a PhD Intern in the DCES research division at the HSRC. Samela Mtyingzane is a PhD Intern in the DCES research division at the HSRC. Carin Runciman is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Social Change, University of Johannesburg.

Data are being collected in the online multilingual University of Johannesburg-Human Sciences Research Council Covid-19 Democracy Lockdown Survey from all willing respondents in South Africa aged 18 or older. It is accessible using the #datafree Moya Messenger App on the #datafree biNu platform, or alternatively using data via https://hsrc.datafree.co/r/ujhsrc. Results are weighted by age, population group and education, making them broadly representative of the population. The survey will be running for one more week and readers are invited to complete the questionnaire.