Issue of the Week: Disease

A World Gone Viral, National Geographic, November 2020 issue

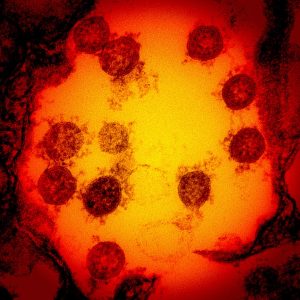

As we write, with the US presidential election eleven days away, the Covid-19 pandemic is about to hit all time highs in infections in the US and is ramping up further around the world, with 42 million infections and 1.1 million deaths in the past nine months and getting worse by the day.

The new November issue of National Geographic Magazine is dedicated to the issue of the pandemic worldwide. It cannot be missed.

The link to the cover article, which links to numerous other articles, is below. It has moving reports and extraordinary photographs from a number of nations worldwide:

GLOBAL PANDEMIC. We’ve been reading and hearing these words for more than seven months now. Sometimes the limits of human imagination are a blessing: If we actually possessed the ability to visualize the globe’s people during this crisis—the same grief and fear spread across so many different settings, cultures, languages—we might not be able to endure it.

But these international photographers’ dispatches, gathered in five different countries over 2020’s spring and summer, begin to distill the enormity and variety of the pandemic experience. Cédric Gerbehaye, his native Belgium at one point registering the world’s highest per capita COVID19 death rate, spent weeks documenting overwhelmed Belgian medical and nursing home workers. Nichole Sobecki, an American who has lived for nearly a decade in Nairobi, photographed the hustle and anxiety of her adopted city’s grapple with quarantine.

In Jordan, new resident Moises Saman explored the country’s massive population of refugees as pandemic lockdown and recession added one more hardship to their existence. An Indonesian travel ban kept Jakarta photographer Muhammad Fadli from making the annual Ramadan visit to his parents’ village; he took his cameras into the streets instead. (How the coronavirus outbreak grew from a few cases in China to a global pandemic in less than three months.)

CÉDRIC GERBEHAYE dressed as advised by the medical workers around him: face mask, face shield, body suit, double bags over his shoes, double gloves over his hands. The outer gloves were plastic, taped to seal out virus. He learned to hold and work his camera through plastic. In a Brussels nursing home he watched an aged woman look into the eyes of the nurse who had come to test her for COVID-19. “J’ai peur,” the woman said.

The nurse took her hands, leaned in close, and said: I’m scared too. She and her team were testing nearly 150 people on that day alone. When she turned to Gerbehaye afterward, her voice was thick in a way that stays with him still; she sounded broken, tough, grieving, and furious, all at once. “No one else can come close to these people,” she said. “If I don’t do this, who will?”

Gerbehaye is 43, the grandson of Belgian and Dutch survivors of the Second World War. It is not uncommon for him, as a photojournalist, to stand in the presence of armed conflict and death. But as he lingered last spring inside hospitals, eldercare facilities, and corpse-transport vans, Gerbehaye understood that Belgians of his generation were witnessing for the first time, as their grandparents had, their own nation in crisis and afraid.

J’ai peur. Belgium’s pandemic numbers were famous for a few March and April weeks, when the country’s per capita COVID-19 fatality rate looked to be the highest in the world. Were Belgian authorities simply counting more honestly, as some contended, than everyone else? In any case the casualties Gerbehaye saw, as he followed undertakers and hospital staff in Brussels and two smaller cities, were also among the living: women and men at the front, caring for the stricken, improvising, overwhelmed.

Outside a hospital in Mons two nurses sat near him one afternoon, silent, slumped, smoking cigarettes on their break. When one rested her head on the other’s shoulder, Gerbehaye thought of the phrase faire corps, which literally means make a body, join together as one. They reminded him of small animals curling into each other for warmth. I have seen your sisters at clinics in Gaza after bombings, he said to himself; like them you’re part of history, even though you’re too tired to care. He raised his camera. The nurses did not look up.

THE PANDEMIC CRIPPLED the mudik, which is what Indonesians call the great holiday migration of city people traveling to see their families in villages and the countryside. Indonesia’s Muslim population is the world’s largest, and the Ramadan mudik is massive. In an ordinary year, as the month of daily fasting comes to a celebratory close, photographer Muhammad Fadli would buckle his wife and daughter into the family’s Nissan van and brave the traffic out of the capital, Jakarta. The trip to Fadli’s hometown takes 36 hours by winding roads and ferry, but his parents are there. Fadli is their only child.

Late this past April, with infection numbers soaring and Ramadan about to begin, the Indonesian government restricted region-to-region travel for six weeks: a “mudik ban,” the Jakarta Post called it. Stuck in the city, Fadli kept working. A photographic assistant drove him through streets that were empty and still, until the morning they rounded a corner and saw a throng—stopped cars, motorbikes, women and men on foot packed shoulder to shoulder, all shoving urgently toward something.

“Pull over,” Fadli said. He pushed up his face mask and hurried out. What is happening? he asked, and without glancing at him, people said, “Bantuan sosial.” Social aid. Rice, masks, and fermented soy cakes, all being handed out by uniformed men on the other side of a closed gate.

The military men kept shouting, “Tolong sosial distancingnya,” please stay apart; we won’t give anything until you stay apart! Useless. Need and anxiety are propulsive forces, especially in a crowd. As the men gave up and swung open the gate, Fadli felt the weight and blessing of his own family’s modest comforts. They had enough to eat. He had work. Indonesians were defying the travel ban already, spreading virus the length and breadth of the archipelago, but he knew the home of his parents was empty of guests: somber, quiet, safe.

A sign points cars and motorbikes to an improvised drive-through: two nurses, waiting to draw blood on the spot for COVID-19 antibody tests. Like the U.S., Indonesia offered sparse, sometimes bungled testing during early pandemic weeks. Portrait artist Sigit Parwanto, carrying samples, counted on orders from tourists at Java’s popular Parangtritis Beach—until last spring, when the visitors vanished.

Fadli’s Ramadan visit would take place by cell phone video chat, and he could picture it even now: his mother’s festive clothing stored away, her hair uncovered with no need for hijab among close family, his father beside her on the couch. They’d greet each other in the Indonesian Ramadan way: “I sincerely request that you forgive my past wrongdoings.” Then they’d settle in to talk.

AT FIRST THE GOVERNMENT shut down nearly everything: borders, businesses, schools, civilian presence on the streets. Tanks and army trucks backed up an around-the-clock lockdown—no exceptions, even to shop for food and medicine. Amman is built on hills, and from his kitchen, photographer Moises Saman could hear the echoes of citywide sirens, the kind used for air raid warnings. He stayed inside with his family until the curfews began to ease, during prescribed daylight hours only, for certain approved purposes only. Then he went to find the places where refugees live.

About 750,000 recent refugees are in Jordan now, grouped into designated camps or scattered into settlements and neighborhoods. They come from as far away as Somalia and Sudan, but the vast majority are Syrians escaping civil war. Photographing inside makeshift dwellings and urban apartments last spring, often in the company of UNICEF workers, Saman saw that the terrible scenarios initially envisioned in the settlements’ crowded quarters—the coronavirus spreading uncontainable sickness and death—had been averted. Jordan’s strict lockdown measures, along with aggressive contact tracing, appeared to have kept the pandemic at bay: Only 15 COVID-19 deaths were confirmed as of late August.

The lockdown’s aftermath, especially for people desperate enough to have fled their home countries, was more complicated. Layers of hardship can accumulate until it’s hard to separate one from another. The pandemic slammed the economy, wiping out informal work that many refugees depend upon. The abruptly closed schools and community centers had been safe places of support for refugee children—especially girls, for whom an ongoing education is the surest protection against early marriage. When lessons moved online and began airing on national television, children with no computer access were trying to complete schoolwork and take exams on their household’s only screen: the family mobile phone.

For refugee and other marginalized children, such as these girls from Jordan’s Dom ethnic minority community, schools and help centers provide support lifelines. But those facilities closed for months during the pandemic.

For Syrian refugees, pandemic repercussions added one more burden to an already tough existence. In the Mafraq settlement, a mother watches her sons with contents of a UNICEF donation box. Their father’s work as a laborer, like much of the informal work done by refugees, vanished during the shutdown.

Smartphone homework uses data; replenishing it costs money. To the list of donation items made crucial in this pandemic—soap, buckets, pencils—UNICEF added a very modern form of aid: data allowances, loaded from afar, to help determined children stay in school.

FROM THE KENYAN CAPTIAL, two voices on Nairobi and the pandemic.

Daniel Owino Okoth: My aka name is Futwax. I’m a recording artist, a sound engineer, a community leader, and I was learning music production. I have a family: a son and a wife. In Kibera we have many stories to tell about how we are living our lives, you know? We tell them through music, through art, and I was doing gigs, traveling outside the county, performing in schools. Teaching people about Kibera, about ghettos around the world. Things were good when the corona was not around. I was hoping to do music videos, but then the corona came.

Nichole Sobecki: Kibera is one of more than a hundred informal communities, as I call them, in Nairobi. I know people use the word “slum,” but these are named places that are deeply creative and entrepreneurial. Kibera is one of the biggest in Nairobi, and on a normal day commercial streets would be bustling with businesses, restaurants, hotels, and shops selling vegetables and meat and used clothing. Energy and hustle. Nairobi is built on hustle. I’ve called this city home for nine years, and it’s a very exciting place to be. Futwax is a great example: He’s a former Mr. Kibera—that’s an annual contest they hold. If you know Kibera, you know Futwax, and early into the pandemic, he realized this was going to be a very real issue for his community.

Daniel: We can’t travel, so it messed up my gigs. And here in Kibera, we don’t have “social distance.” We share toilets. We share entrances and exits of houses. We share where we iron our clothes after washing. We don’t have supermarkets; we share kiosks. We saw people who were taken away by ambulance, people from the slums who were put into government isolation centers, you know? So I decided to take responsibility in my own hands. I went to the management at Kibera Town Centre.

Nichole: The Town Centre opened a few years ago, in the heart of Kibera. It’s a community-operated space—clean water, laundry, bathrooms, skills training, access to credit and computers. It’s also a gathering spot, with a surrounding market, so they’ve set up speakers outside for music and messages. Now Futwax is often on the decks there or walking through the community with a megaphone, talking about the coronavirus and how to keep one another safe.

Daniel: The center has a recording studio where I was learning music production, and at the beginning of the pandemic, they closed it. But I said we could record corona radio jingles in different languages. They said OK, if you are careful to bring people in only one at a time and disinfect in between. So with people who speak Luo, Luhya, Swahili, Kisii, and Nubian—we have many languages here—I recorded them saying: Please wear a mask! If you are sneezing, kindly sneeze on your elbow or arm! If you are talking with someone, kindly talk from a distance!

For this father and son, self-quarantine means practicing swings from the roof of their Nairobi apartment building. The exclusive Muthaiga Country Club, where they usually golf, announced a temporary closure last spring, “to keep our country safe.”Determined to help propel Kenya’s vigorous fashion industry despite pandemic restrictions, stylist Wambui Thimba models in her apartment for roommate and photographer Barbara Minishi. Thimba’s ensemble is a creation by Kenyan designer Laviera, who explains the garment on Instagram: “You really don’t have to do much with a statement blazer. It does all the work for you.”

Nichole: His own song is really catchy, and it’s been being played not only in Kibera but around other parts of Nairobi as well. He understands people’s concerns here and speaks Sheng, among other languages. Sheng is Nairobi’s urban language, a dynamic Swahili-based slang that can vary neighborhood by neighborhood, month by month. We often see imposed public health messaging, outsiders trying to come in and educate a community—but actually, what he’s doing resonates so much more powerfully.

Daniel: People who said they didn’t want to sanitize, to wear a mask—this hurt me in the heart. I’m asking people: What responsibility are you taking as a citizen? As a businessman, when you are serving your customers, are you telling your customers to pay the electronic way? Do you have a handwashing station? So I went into the studio and expressed it in lyrics. I’m sensitizing the community, mixing my languages, some good Swahili, some English—and I’m talking that Sheng. A mama mboga is a small businesswoman who sells vegetables. A wochi is a watchman. Wewe means you, like, “Hey wewe, Nichole!”

“Have You Sanitized?” by Futwax (chorus)

Have you sanitized, mama mboga wewe?

Have you sanitized, wochi wewe?

Have you sanitized, businessman?

Have you sanitized, ghetto gal, ghetto boy boy?

Have you sanitized, president, policeman, traffic police?

Have you sanitized, preachers preachers?

Have you sanitized, worldwide worldwide worldwide worldwide worldwide?

HOW MANY NUMBERS have you tried to absorb in the months since this began? How many case tallies, risk percentages, per capita infection rates, daily updates in the counting of the dead?

A pandemic is a story told in torrents of numbers. In the newsroom of the Detroit Metro Times, where she worked as a writer, Biba Adams took in one number after another as the new coronavirus spread—out of China, across Europe, into the United States, into Michigan. During the second week of March, health authorities confirmed the first COVID-19 cases in Detroit. A few days later, Adams’s mother developed a cough.

Wayne Lawrence met Biba Adams in June, as he visited three U.S. cities photographing the pandemic-bereaved: women and men who told him about losing a loved one to COVID-19 or its complications. By that time the virus had killed Adams’s mother. It killed her aunt too, and her grandmother. Radio and television programs put Adams on the air, and whenever she spoke, she was direct about both her grief and her fury. If political leaders had behaved differently starting with the earliest warnings, Adams said over and over, then her family members—her mother was a 70-year-old working woman, part of a law firm, a lover of gospel music—might be alive today.

“To lose one’s mother is one thing,” Adams said in a phone conversation in late July, as the U.S. pandemic death totals were pushing past 150,000. “To lose her as one of 150,000 people is even more painful. I don’t want her to just be a number. She had dreams, things she still wanted to do. She was a person. And I am going to lift her name up.”

Elaine Head. That is the name of Biba Adams’s mother. All the portraits Lawrence made, in these centers of concentrated COVID-19 damage, are of the individually bereaved—because their faces, like the names of the dead, are as important as the numbers. The young man in a tie, with his arm around his fiancée, is a Louisiana chemical plant boilermaker named Derrick Chaney; he says his big brother Marsha Chaney was 35 when he died of COVID-19 in a hospital intensive care unit. Counting Marsha and Derrick, nine siblings were in the family home, in the small town of Greensburg, northeast of Baton Rouge. Marsha was a truck driver. He’d been a high school football star, studied engineering in college. “We didn’t have friends,” Derrick says. “We had us. He was, like … the pick of the litter, the chosen one. He was the one who kept everybody together.”

The two young women with their mother’s arms around their waists—those are the Segui sisters, Morit and Chloe. Their father, Yves-Emmanuel Segui, had emigrated from the Ivory Coast, where he trained as a pharmacist. Daily life there is in French; in New Jersey, as he raised his family, Segui kept failing the English-language pharmaceutical licensing exam. Every time he failed, he began studying again to retake it. The reason the New York Times could headline the obituary “Indomitable Bronx Pharmacist,” after COVID-19 killed him at 60: On his eighth try Segui passed the exam, and he finally had found a pharmacy job, to which he commuted by bus and train from Newark, three hours each way.

The woman in a white sweater, her head erect as she weeps—that’s Elaine Fields, whose husband, Eddie, was 68 when he died in April in a Detroit hospital. He was a retired General Motors plant worker, an excellent bowler, a classic car aficionado restoring a 1949 DeSoto. The woman whose pandemic mask bears the face of a beautiful little girl—that’s Detroit police officer LaVondria Herbert, married to Detroit firefighter Ebbie Herbert. They’re the parents of Skylar Herbert, gymnast and math whiz. June 3 would have been her sixth birthday. She was their only child.

Tragedies are commonplace, a song by the late gospel artist Walter Hawkins begins.All kinds of diseases. People are slipping away. When Biba Adams collected her mother’s possessions from the hospital, she found the printed lyrics folded up in Elaine Head’s wallet. Hawkins wrote the song many years ago; it’s about gratitude, not disease, and the chorus thanks Jesus. But the lament in its verses presages a virulent modern contagion, a rickety national health system, and a deeply stratified society, all working together to smite with extra ferocity America’s racial minorities and the poor. People can’t get enough pay. No place seems to be safe.

The lyrics aren’t precisely true, amid the pandemic of 2020. Some people can get enough pay. Some places are safe, or at least safer than others. And some tragedies are not common at all.

Adams framed the lyrics and hung them on her dining room wall. In July she finally was planning the memorial for her mother; she wanted it in her own backyard, where masked guests could listen to Hawkins’s song and reminisce. She’d ordered a package of live butterflies to release into the air—her mother would have liked that, Adams thought. “I need to have this service,” she said. “I need to close this passage.”

(Too see the majority of photographs and additional commentary go to the link.)

. . .