Message of the Day: Disease, Human Rights, Personal Growth

Are Your Choices Making the Pandemic Worse?, Politico Magazine, 11/25/20

Yesterday was the Thanksgiving holiday in the US, kicking off the holiday season countdown to Christmas and the New Year. A season unlike any before it, after a presidential election unlike any before it, and a pandemic upending the world for most of the year.

A season, as we have written before, detached from its meaning long ago, hopefully to regain it in the universal values of peace, justice and equality being applied. As always, we’ll be back to that.

But for this season, this year, tragically, it could aptly be named the superspreader season.

The day before Thanksgiving, Politico Magazine gave us the gift of an in-depth yet succinct look at where we are in the pandemic, where we are going depending on our behavior and that of those with governing responsibility, and why.

Here it is:

Are Your Choices Making the Pandemic Worse?

By Jack Stanton, 11/25/20 Politico Magazine

How does an epidemiologist think through the little decisions each of us make during the coronavirus pandemic? Boston University’s Ellie Murray explains.

The global coronavirus pandemic can be seen many ways: as an act of God, a consequence of a shrinking world, a biological fluke. But if you’re an epidemiologist, looking at the grim moment America finds itself in right now, you also see it another way: This was a choice.

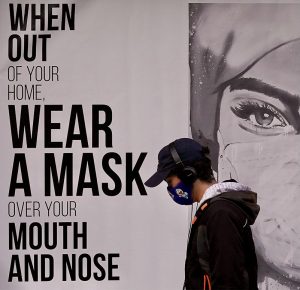

For months, each of us has made a cascade of seemingly small decisions about how to live during the pandemic—whether or not to wear a mask, whether or not to quarantine, if and how to socialize, whether to travel for holidays or stay home. And then there are the choices that we have made as a country. Politicians have chosen to require masks, or push safety messages, or close bars—or they’ve chosen to ignore the virus and do none of those things.

Cumulatively, those decisions have added up to the moment we’re in. As families gather for Thanksgiving throughout the U.S., the country teeters on the brink of a coronavirus catastrophe. Records are being shattered by the day as new coronavirus cases and Covid hospitalizations surge upward throughout the country—and, because people are about to choose to spend holiday dinners with family, it’s likely to get worse.

“The Thanksgiving increase [in Covid cases] is going to roll into a Christmas increase and a New Year’s increase,” says Dr. Ellie Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University. “The current wave we’re in may not peak until sometime in — maybe — February.”

At Boston University, Murray leads the epidemiology department’s Causal Lab, which focuses on helping to improve and expand the use of evidence-based decision-making in everyday life. With Thanksgiving upon us and the holiday season at the doorstep, she wants people to pause and take time to talk with their families and loved ones about the Covid-related decisions they’re making in their own lives.

How does an epidemiologist think through those choices? And what exactly are we facing in the weeks and months to come? To talk through it, POLITICO Magazine spoke with Murray. A condensed transcript of that conversation is below, edited for length and clarity.

In terms of the coronavirus, given both the sharp increase in cases and widespread travel over Thanksgiving — and given the incubation period for the virus — what should we expect in two or three weeks?

Right now, across most of the United States, cases are trending up, hospitalizations are trending up and deaths are trending up. That’s a really bad situation to be in going into the holidays.

I’ve seen people say things like, “We just need to get through the next week, and then cases will start coming down.” No. If there are transmissions on Thanksgiving, those will start to be recorded as cases over the following 14 days, then reflected in hospitalizations a week or so after that, and in deaths around Christmastime. Even if everyone stops what they’re doing today, we’re still going to see an increase in cases for the next two weeks, because those transmissions have already happened.

There’s no plan for a coordinated national lockdown or anything like that. And that means the Thanksgiving increase is going to roll into a Christmas increase and a New Year’s increase. The current wave we’re in may not peak until sometime in—maybe—February. There will be a lot of illness and hospitalization and death. It’s a really bad situation. That’s the pessimistic view of what to expect.

That may be a pessimistic view, but do you think it’s also the realistic view?

Yeah. You know, at any time, there could be a set of lockdowns put in place, and if they are long enough and severe enough, that would force the curve down. After about 14 days of a lockdown being initiated, we start to see the case curve trend down or at least plateau. But it seems unlikely we’ll have any kind of federal lockdown before January 20 [Inauguration Day].

One might hope that states—as they get overwhelmed and our hospital systems get completely inundated—will start instituting more local-level or state-level lockdowns. And if that happens, we’ll start to see the curves come down. Really, whatever happens with the case trajectory is about what politicians decide to do.

In the spring, we heard a lot of concern that the number of Covid patients who needed to be hospitalized would completely overwhelm hospitals. For the most part, we ended up avoiding that. Are we looking at the realistic possibility of that starting in the next couple of weeks?

Definitely. We’re hearing from a number of areas in the country where hospitals are already overwhelmed, where all of their Covid or ICU beds are full.

In the spring, a couple of things made it possible for us not to not get to that point. One was the lockdowns, which helped flatten the curve. But another is that the outbreaks were relatively localized, so health care workers in New York could be supplemented with health care workers from the Midwest or Florida or California, who could come to New York and provide respite.

So you’re saying that because Covid is now so widespread, it’s not localized. And that means that there isn’t a surplus of doctors and nurses we can ship in from another state, right?

Exactly. When the outbreak is everywhere in the country, there’s nowhere for help to come from. There’s nowhere for backup to come from.

Places to put people who are sick? That’s something we can potentially find: In the spring, New York was able to build field hospitals and have Naval hospital boats come in. But people who are trained to care for the critically ill? That’s a really limited resource, and those people are exhausted. They’ve been doing this since January, February, March. A lot of them have gotten sick and died themselves. Many who survived are dealing with grief from watching so many people die, including their friends and co-workers.

That’s really the biggest concern: We are burning through our capacity in terms of personnel and their resources, energy and resilience levels. There’s nobody else to come in and help—unless maybe if the federal government were to say that nurses and doctors licensed in Canada or Spain or wherever can come and supplement our workforce. But the government would have to make that decision—health care workers who aren’t licensed in the U.S. are not necessarily able to work here.

The public appetite for “flattening the curve” has abated. Why do you think that is?

I think there are a couple of reasons. The public health community viewed lockdowns and flattening the curve as having two goals: one, preventing hospitals and health care systems from getting overwhelmed in the spring; and two, to buy us time to implement and ramp up more concerted, coordinated public health responses—widespread testing, contact tracing, isolation and quarantine of people who are either exposed or known to be infected.

But in general, a lot of those ramp-up things didn’t happen—definitely not in a coordinated way at the national level. And because a coordinated public health response wasn’t put in place federally during the lockdowns, for a lot of people, they didn’t see “flattening the curve” as doing anything. People were giving up a lot. Many lost their jobs. They couldn’t interact with their friends and family, and it was starting to be nice and summery outside, and everyone wanted to get back out there. And if we’d done what we were supposed to do, they could have. But we didn’t actually do that. So that was one problem: People got sick of lockdown.

I think December 31 was the first time I saw anything about this “unexplained pneumonia.” It was like, “OK, this is something to pay attention to. Any minute now, the established set of processes is going to kick in, and it’ll be dealt with.”

Days went by. Then weeks, then months, and it was like there was … nothing. There’s a process that should have been activated. And it wasn’t. There was no response. We started hearing that even the stockpiles of masks didn’t actually have any masks in them, or they’d expired. Things that should have been relatively straightforward were not. That is so different than I expected.

We kept coronavirus cases low in the spring, but [lacking a coordinated national response,] we kicked the can down the road into summer. Then we had a summer peak and a little bit of an attempt to control that, but mostly just kicked the can down the road into the fall. And now, all of our bills are coming due.

I’m curious, and feel free not to answer if this is too personal: Is it depressing to be an epidemiologist at this moment?

[Pause] It’s really … Yes, it’s depressing. It’s frustrating. People ask me all the time: “What’s changed? What’s new? What’s the new solution?” The solutions right now are the same solutions they were in January, February and March. We just need to implement them.

Yes, we’re developing vaccines, and those vaccines are using a slightly different technique than in the past, and that has allowed us to develop them more rapidly. And yes, we’re learning which treatments work and which don’t, and we’re getting a better idea of how Covid itself is transmitted. But you don’t need to understand all those things to respond successfully to an infectious disease outbreak.

New Zealand has done a fantastic job. Vietnam has done a fantastic job. Mongolia has had no local transmission and no deaths because really early on, they recognized the severity of the problem and put into place the things that have worked for public health outbreak-response for the last 400 years.

There’s this village in the UK called Eyam. During the Black Plague, it was the northernmost point in the country that the plague reached, because when it got there, the people made a decision as a town that they were going to lock down and completely cut off contact with the outside world. At the border of the town, there was a stone with a depression in it, and they poured vinegar in that and would leave money in the vinegar [which they intended to use as a disinfectant]. People from the nearby town would bring them supplies and leave them by the stone and take the money. And a huge number of people in Eyam died of the black plague, but it didn’t spread beyond its borders.

This was before we even had even an understanding of the germ theory of disease! They didn’t know what caused the plague. They certainly didn’t know that fleas were responsible for transmitting it—it was a mystery. But the town is still there. It’s vibrant, and there are people whose families have lived there for hundreds of years.

We have better medical treatments now. We understand what a virus is and how viruses work. But our general public health response tools are basically the same: If you might be infected, don’t come into contact with people who are not infected. It’s frustrating that is still so hard to implement.

That example really shows an understanding of causal relationships. You do a lot of work on that topic. With coronavirus, when it comes to causal relationships, most things are not 100 percent dangerous or 100 percent safe. How should we think through those decisions and weighing risks?

A lot of times, really loud messages try to make things black and white—“always wear a mask” or “never wear a mask,” instead of “wear a mask if you’re going to be within 6 feet of somebody or if you’re going to be in a shared indoor space”—but really, there are two aspects to think about.

First, there’s the risk of getting infected and transmitting that infection to somebody else. I still don’t think it’s widely understood that you can transmit infection even if you feel totally fine. A lot of people think, “If I feel sick, I’ll just stay home.” But you can feel totally healthy, infect grandma or your neighbor, and realize a couple of days later that you were sick. We need people to get more comfortable thinking about that.

Second, which activities are risky, and how risky are they? This is where the idea of a continuum comes in. There’s a rhyme that [epidemiologist] Bill Miller from the Ohio State University came up with for the four dimensions to think about: “Time, space, people, place.”

Time: How much time are you spending doing this activity? The more time you spend, the more chance there is for transmission. The less time you spend, the less chance.

Space: How much personal space do you have? Are you able to get a distance from people? Is it 6 feet or not? If you’re singing or cheering, you’ll need more space because your respiratory particles can travel further than 6 feet. The more personal space, the better. If you’re out in the woods by yourself with no one around, you don’t need that mask on, because there’s no one to transmit to or get infected by.

People: How many people are there? Are these people you see regularly? Are they part of your core bubble, or strangers? It’s safer to spend time with mostly the same group, and safer to have fewer people in that group.

Place: Where is this? Certain places are more conducive to transmission. A small room where everyone’s packed in together is riskier than a large space. A museum is typically a much larger space than a bar, which is generally smaller with a low ceiling. Outdoors is safer than indoors. Indoors with the windows open is safer than indoors with the windows closed.

Think through all of that. What are the activities that I must do? What are the activities I just want to do? How risky are they? How can I make them a little bit safer?

Is there anything that has surprised you about the way people have been making decisions during this pandemic?

Yes and no. It’s not necessarily the way people have been making decisions; it’s that I hadn’t really grasped how little anyone outside of epidemiology really understands about public health.

Epidemiology and public health, they’re not widely taught. They’re not taught in high school or elementary school. Until very recently, they weren’t even taught in undergraduate college. We see news stories about, for instance, someone who was told to quarantine, and it turns out they had 100 people over to their house for a party, and they say, “But I didn’t leave the house.” Well, that’s not what “quarantining” means. Quarantining means you don’t leave the house and nobody comes into the house and you don’t have contact with anyone.

It didn’t occur to me that people didn’t already deeply understand the concept of quarantine. And almost always, “quarantine” is used in the media when really it should be “isolation.” In public health, “isolation” is the term we use when talking about restricting the contacts of someone known to be infected. But people, if you poll them, think “quarantine” is for sick people, and “isolation” is for people who are not sick—it’s the opposite.

This is an example of something we in epidemiology have to grapple with. We have really specific terminology that mean really specific things—and it’s often counterintuitive, almost the opposite of what nonepidemiologists might think. If you’re not an epidemiologist, then you don’t hear our epidemiologist-specific meaning. But how can we expect the general public to understand our messages when we’re basically talking in a secret code where words they think have one meaning actually have a different meaning when we use them?

A lot of times, I’ll see something and think, “What are people doing?” Their decisions surprise me until I step back and think about what we did wrong in communicating about it.

Over the past few weeks, we’ve had a lot of positive news about coronavirus vaccines. Are you concerned that the prospect of vaccines in the coming months will make people more flippant about following Covid guidelines?

This is always a concern in public health, and it’s actually pretty hotly debated. It falls under this idea of “risk compensation”—that people have a certain level of risk that they’re comfortable with, and the question is, if you create circumstances where they perceive that something they’re doing is now safer, will they take more risks?

To a lot of people, this sounds like a thing that theoretically probably happens. But when we actually look at data, it doesn’t appear that people really do that—at least not in a clear, measurable way. On a population level, it’s still a bit of an open question. You might think about, for example, when there were lockdowns, we all stayed in our houses, but when it was said that masks can make us safer, people put on masks and went outside their homes and cases spiked.

It feels like it should be a thing. But the bottom line is we really don’t know.

Last question: With Thanksgiving this week, whether we gather with family in person or remotely via video conference, what should we have in mind while discussing the pandemic?

I hope that people will be thinking and talking—especially with their families—and being really open about what precautions they are and aren’t taking, and that they’ll be comfortable sharing that information and accepting what the other person is going to do in response.

I hear a lot of people say things like, “I stayed home for two weeks, then went to see my grandma, and my uncle showed up. And it turns out he’s been visiting her every day after going to the bar. I had thought I was safe in that room.” Or people who say, “I showed up at a gathering that I thought was going to be small, but when I got there, it was a much bigger crowd, and no one else was wearing a mask.”

People are getting an idea of what they themselves are comfortable with, and that’s helpful. But we now need to get comfortable talking about it with each other: What are you doing? Is that something I am comfortable with? If not, then you need to be OK with me saying, “Sorry, let’s just chat on the phone or on FaceTime.”

We need people to be upfront and open and honest about what risks they are and aren’t taking, and what risks they are or aren’t comfortable with each other taking. That’s the next step, especially over the holidays, when what people are doing in terms of gathering with each other can be emotionally fraught.

- “UN inquiry finds Russia’s deportations of 20,000 Ukrainian children amounts to crimes against humanity “, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Reuters

- “Brooks and Capehart on Trump’s decision to launch strikes on Iran”, PBS NewsHour

- Issue of the Week: War

- “The Original”, The New Yorker

- “Big Change Seems Certain in Iran. What Kind Is the Question”, The New York Times

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017