Issue of the Week: Human Rights, Disease, Environment, Hunger, Economic Opportunity, Population, War, Personal Growth

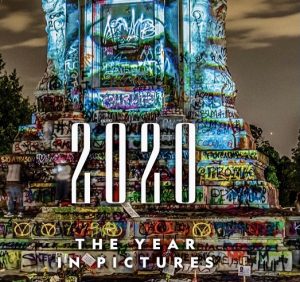

2020: The Year In Pictures, National Geographic, January 2021 Special Issue

The introduction for the cover piece in the January 2021 Special Issue of National Geographic, posted online 9 days ago notes:

In our 133 years, National Geographic has never singled out one year for a retrospective like this. But if ever a year demanded that, 2020 does.

What else could be said after that? Here it is, in photography, video and text:

54 PHOTOGRAPHS FROM AN UNFORGETTABLE YEAR

BY SUSAN GOLDBERG

Many superlatives can be applied to 2020, most of them negative. “Worst year ever,” I’ve heard people say—a subjective judgment we each would make differently. But it was unquestionably a harrowing year, marked by COVID-19’s tragic death toll, the hurtful racial strife, and the divisive political environment.

In this special issue, “The Year in Pictures,” we’ve documented 2020 through the work of some of the world’s most gifted photographers. In our 133 years, National Geographic has never singled out one year for a retrospective like this. But if ever a year demanded that, 2020 does.

In some respects, making this issue was not hard. We added more than 1.7 million images to the National Geographic archive last year—likely fewer than usual because the pandemic complicated travel assignments, but still a wealth of material. The challenge was narrowing that to fewer than 60 images that most powerfully capture this astonishing year.

As we chose photos, the underlying themes of 2020 began to emerge. The year tested us in more ways than we can list, from the still growing body count of the pandemic to disasters around the globe: hurricanes, wildfires, locusts. It isolated us from one another: Schools and offices closed, and we were behind masks, socially distanced even from our own families. Yet it was a year that also empowered us, as the death of a man named George Floyd at the hands of police sparked an urgent, diverse movement for social justice.

When you look through the images of 2020, you can find hope too, if you care to see it—if not for this moment, then for a brighter future. I see it in the glowing horizon in a photo of a storm sweeping across Lake Michigan, by Keith Ladzinski. I see it in Davide Bertuccio’s photograph of a couple getting married in Italy, the veiled bride behind a white lace mask.

We won’t miss 2020. We won’t forget it. And together, we greet 2021.

Thank you for reading National Geographic.

VIDEO: Go behind the scenes with National Geographic editors to see and hear how this issue came together—from selecting the most powerful photographs to deciding on the themes, design direction, and cover.

THE YEAR THAT TESTED US

VIRUS, PROTESTS, AND CLIMATE CHANGE RESHAPED OUR WORLD

TARGETING SYMBOLS OF OPPRESSION

09.08 TUSKEGEE, AL A monument to the Confederacy stands at the heart of Tuskegee, the site of the historically Black university where Booker T. Washington was president and the Tuskegee Airmen trained. After the statue was vandalized, officials of the majority Black city covered it with a tarp while they figured out how to remove it.

A BACKLASH AGAINST SYSTEMIC RACISM

06.18 RICHMOND, VA The statue of Robert E. Lee is transformed into a Black Lives Matter monument with a projection of George Floyd’s portrait. “It’s time for the healing to start,” tweeted Levar Stoney, Richmond’s mayor. “For public safety, for our history, for our future— the monuments to the Lost Cause are coming down.” Lawsuits attempted to block removal of the statue.

IN ANGER AND PAIN, PEOPLE TAKE TO THE STREETS

05.29 MINNEAPOLIS, MN The killing of George Floyd by city police officers ignited protests across the United States and around the world against police brutality. David Guttenfelder covered the demonstrations close to his home in Minneapolis. “There’s not one protester, not one attitude—it’s all driven by grief,” he says. “Grief over this man but also grief of a lifetime of this pain.” Four days after Floyd was killed, protesters set fire to the precinct building where the officers were stationed. The police fired rubber bullets and tear gas at the crowd. Amid the anger and chaos, Guttenfelder heard someone shouting: “We’re hurting. We’re hurting.” The following day, a protester received first aid after being struck near the eye during another clash.

WORLD IN CHAOS

BY CYNTHIA GORNEY

Merriam-Webster, the dictionary company, keeps track of words people look up most frequently online—not necessarily because the inquirers don’t know what the words mean, but because a formal definition sometimes helps sharpen our understanding of events. In 2020 “apocalypse” surged early. So did “calamity,” “pestilence,” “panic,” “hunker down,” and “surreal.”

This was in the winter and early spring, when the daily effort to grasp what was happening around us seemed already beyond our imagination. In the summer, after the killing of George Floyd, “racism” lookups spiked. “Fascism.” “Empathy.” “Defund.” In September: “mental health.” The western United States was on fire by then, the southeastern states so rain-battered that the National Hurricane Center exhausted its usual storm names list and started in on Greek letters. Winds blew toxic wildfire smoke across thousands of miles. One morning thick smoke turned the sky deep orange around San Francisco Bay; it stayed that way all day, like a biblical plague of darkness.

Swarms of locusts? We had those too, ravaging swaths of Africa and Asia. As this issue was being finalized, the global pandemic was nowhere near contained in the U.S. and many other parts of the world; for those of us who have survived, there were weeks—months—when the entire year felt like some demented experiment in emotional carrying capacity. We know humans can be terrified, heroic, bewildered, grateful, vicious, mournful, selfless, hopeful, cynical, furious, and resolute. It took 2020 to make some of us understand the extent to which each of us can be so many of those things at once.

THE ANXIETY OF BLACK MOTHERS

01.25 LITTLE ROCK, AR In his project “Stranger Fruit,” Jon Henry poses Black mothers with their living sons in the form of a pietà, in which a grieving Mary holds the dead body of Christ. The work is his response to police violence against the Black community and to memories of his mother’s incessant worrying as he was growing up. Henry asked his subjects to reflect on these scenes. “I feel sad—sad that mothers actually have to go through this,” one woman said. “My son was able to get up and put back on his clothes. Others, not so much.” This family is in front of Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas, scene of a confrontation over school integration in 1957.

EXTREME MEASURES AND SHORT SUPPLIES

04.23 BOGALUSA, LA The pandemic caught many health-care systems short of emergency supplies, a situation exacerbated by uneven government responses to the crisis. Physician Gerald Foret dons a protective mask before seeing COVID-19 patients at Our Lady of the Angels Hospital in Bogalusa. The hospital was running low on N95 masks, so Foret used a spare respirator that was on hand. The full-face mask offered nearly complete protection from airborne particles when he entered the negative pressure unit where coronavirus patients were treated.

ON THE FRONT LINES IN A GLOBAL CRISIS

04.14 ISTANBUL, TURKEY A city employee disinfects a street in Beyoğlu, a tourist district empty of tourists. When communities shut down across the world, many people could retreat to their homes. Others, newly deemed essential, had to keep working. Like many countries, Turkey sent out armies of workers in protective gear to spray the streets, hoping to contain the virus and, perhaps, reassure its citizens that action was being taken. The World Health Organization later warned that this method was ineffective at halting the spread of the coronavirus and that the disinfectants could potentially harm people’s health.

ATTEMPTING TO IDENTIFY THE SICK

05.02 TIERRA DEL FUEGO, ARGENTINA Governments have struggled to halt the spread of coronavirus in their communities. In Ushuaia, the capital of Tierra del Fuego, one of the hardest hit regions in Argentina, the local government tried installing thermal scanners at the entrances of the two biggest supermarkets. As the only shops open during lockdown, the stores drew people from across town; officials thought the cameras would help identify those with a fever. A doctor and a city official monitored each device and sent home customers with elevated temperatures. But the scanners weren’t effective at identifying the sick: They only measure skin temperature, which fluctuates with the external environment.

DESPERATION AMONG THE MOST VULNERABLE

05.06 LUCKNOW, INDIA Financially, the pandemic landed hardest on low-income people. In India an estimated 139 million people are internal migrants, having moved from their rural homes to cities to work for daily wages. When the country went into lockdown, millions lost their jobs. Afraid of food shortages, many tried to return home. Public transportation was shut down, so they walked or biked or caught a ride on a truck, like this one near Lucknow. Eventually the government arranged for trains and buses to transport migrant workers. The International Labour Organization said the pandemic will push 400 million of India’s informal workers deeper into poverty.

LOSING LOVED ONES, UNABLE TO MOURN

06.15 DETROIT, MI In April, Elaine Fields lost her husband, Eddie, and her mother-in-law, Leona Fields, to complications from COVID-19. Two months after Eddie’s death, she stood by his grave in Detroit and cried. The inability to gather family members for a funeral weighed on Elaine, who also hadn’t been allowed to be with her husband of 45 years when he died. “Our mourning has been stunted,” she said.

NOT JUST A STATISTIC

06.10 DETROIT, MI “She was more than a number—she was a person,” Biba Adams said of her mother, Elaine Head, who died of COVID-19 complications at age 70. Standing outside her home in Detroit with her daughter, Maria Williams, and granddaughter, Gia, Adams grieves for the family she lost in the pandemic, including her grandmother and aunt.

A MOTHER AND SON FUNERAL

06.05 LONDON, ENGLAND Relatives and friends gather for the double funeral of 104-year-old Alexteen Alvira Roberts and her son, Brandis Metcalf Roberts, 79. Brandis died from COVID-19 complications in a nursing home. Alexteen, who came to the U.K. from Jamaica in 1955, died of natural causes. In England and Wales, Black people have been roughly four times as likely as whites to die from the virus, according to the Office for National Statistics. The high death rate reflects centuries of inequalities that minority groups have faced.

A FINAL BLESSING

04.17 NOVARA, ITALY A priest in the northwestern Italian city of Novara blesses coffins arriving from Bergamo, one of the early centers of Italy’s outbreak. Morgues and crematoria were at capacity there, so the Italian Army was dispatched to move bodies elsewhere in the region to prepare them for cremation or burial. For some families, weeks went by before they found out where their deceased relatives had been taken. Funeral home employees became frontline workers, struggling to cope with the mental and physical toll of a virus that devastated their communities.

EXPLOSION FUELS CALLS FOR CHANGE

08.12 BEIRUT, LEBANON In August an explosion of stored ammonium nitrate in Beirut’s port tore across historic neighborhoods, leveled buildings, killed some 200 people, and injured 6,500. Ariana Sursock, 18, was in her family’s home, the 1870 Sursock Palace, with her 98-year-old grandmother, who later died from injuries caused by flying glass and debris. The explosion, linked to a lack of government oversight of safety protocols, led to protests and calls for political change. “I’m not going to start the restoration before we know where we are going [as a country],” said Roderick Sursock, Ariana’s father.

AN APOCALYPTIC FIRE SEASON

09.10 LAKE OROVILLE, CA California’s North Complex fire scorched more than 200,000 acres in just 24 hours this past September. The conflagration started as two separate fires in August during a powerful lightning storm that swept across Northern and central California. Weeks later, the fires, stoked by vicious winds, merged and exploded in size. The North Complex fire quickly destroyed much of the town of Berry Creek and killed 15 people—a grim reminder of the catastrophe that struck Paradise, California, just 40 miles to the northwest, in 2018. Cal Fire, a statewide firefighting and emergency services agency, says that fires in California and the West have grown larger, hotter, faster, and more dangerous, particularly in the past several years. There are a few reasons for this: A century of overzealous fire suppression ignored the role of natural fires in maintaining forest health. In addition, a population boom during the past half century has seen homes and towns proliferate on the edge of wild areas. Years of drought left dead trees to fuel the fires, and climate change gave California its hottest August ever recorded.

ON THIN ICE

02.29 NEAR MADELEINE ISLANDS, QUÉBEC Blood stains the ice where harp seals give birth in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Pups need solid ice to survive, but a warming world and shortage of stable ice in recent years have led to a rise in pup deaths. The situation could eventually prompt this population of harp seals to leave the gulf in search of increasingly elusive ice nurseries.

IN EAST AFRICA, A STORM OF INSECTS

03.05 BARSALINGA, KENYA In a year of plagues, East Africa got an extra one: desert locusts. The swarms, which began moving into the region in late 2019, became a terrifying threat to Africa’s farmers. In January, Kenya had its worst locust outbreak in 70 years. The insects flourish when arid areas get heavy rain and blooms of vegetation, triggering a population boom. Winds from the Arabian Peninsula push the swarms into the Horn of Africa, leading to hunger for millions of people. A single swarm can swell to 70 billion locusts and destroy more than 300 million pounds of crops a day. Even a smaller swarm of 40 million can eat as much in a day as 35,000 people.

LOCKED DOWN, STRESSED OUT; OUR SOCIALLY DISTANT WORLD

A KING IS LOST TO THE VIRUS

07.04 NEW ORLEANS, LA The crown from Larry Hammond’s 2007 reign as Mardi Gras Zulu king rests on a chair at his New Orleans home. The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club crowns a king each year in a tradition that stretches back officially to 1916. Hammond died on March 31 of complications from COVID-19. He was a Vietnam veteran and retired U.S. Postal Service worker. Long before Hammond was king of the carnival, famous New Orleans residents such as Louis Armstrong held the title. The virus hit the 800-member social club particularly hard, killing at least eight members and sickening dozens more.

THE EMPTY SCHOOL

03.10 KRAKÓW, POLAND Jagiellonian University, founded in 1364, has survived religious upheaval, annexations, and world wars, in addition to the deportation of 155 academics to a German concentration camp in 1939. On March 10 the school suspended lectures and closed many campus operations, emptying one of the world’s oldest and most resilient learning institutions. The main reading hall, shown here, turned desolate. Schools around the globe made similar accommodations. From preschools to law schools, educational leaders are grappling with how to reopen safely. For those at Jagiellonian, the 2020-21 school year is a blend of online and in-person learning.

A COVID-19 VICTIM BECOMES A MODERN MUMMY

04.18 INDONESIA The body of a suspected coronavirus victim, wrapped in plastic, awaits a body bag in an Indonesian hospital. The multiple layers were part of a hospital protocol to help suppress the spread of the virus. As is the case with most victims, family members were not allowed to say goodbye. The uproar over this photo, first published in July by National Geographic, thrust photographer Joshua Irwandi into the spotlight. Celebrities and government officials in Indonesia had denied that COVID-19 was an issue in the country, which had lifted many social restrictions. This picture said otherwise. “It has galvanized and renewed discussions of COVID-19 in Indonesia just as the country was then preparing for a ‘new normal,’” said Irwandi. It laid bare a reality in a country where more than 200 health professionals have now died of COVID-19. “It was our wake-up call,” said Irwandi. “It illustrated the statistics that we seemingly grew numb towards.” For Irwandi, the photograph and its aftermath were reminders of the power of a single image.

TOGETHER, ALONE

BY NINA STROCHLIC

Some isolations are intentional—think astronauts, mountain climbers, monks—but for most of us, social interaction is a life-giving electric charge. The year 2020 pulled that plug. In March the world tiptoed into isolation: Gatherings were banned, schools and offices closed. Stay-at-home orders cast an eerie silence over the world. Any setting that fostered interaction was imbued with fear.

The era of coronavirus challenged our definitions of isolation. Was it being separated from our friends and family? Stuck outside our country, or kept from our work and education?

As Brazil became a focal point of the pandemic, residents of the Copan apartment building, in São Paulo, shut themselves inside, afraid of how easily the virus could engulf Latin America’s largest residential structure. Even in the midst of 1,160 homes filled with artists, architects, and designers, life grew quiet and lonely.

Staying home was a privilege. Essential jobs and sheer necessity forced many to choose between their health and their responsibilities. In Bergamo, Italy, one of COVID-19’s early epicenters, funeral director Antonio Ricciardi so feared infecting his family that he slept on the sofa bed in his office for two months. “I was afraid of dying,” he recalls. “I have never experienced this fear before.”

Death, too, became a solitary event. The funeral for Marie Therese Wassmer, 89, was held outside the small city of Mulhouse, a flash point of the outbreak in France. She hadn’t been tested for the virus, but was buried like a victim. Under lockdown, neither her friends nor her family attended the funeral. As a priest and four undertakers laid her to rest in a sealed coffin, the undertakers prayed over her, as though they were family.

NURSES PUSHED TO EXHAUSTION

05.01 MONS, BELGIUM Taking a brief break during ceaseless frontline work treating patients with the coronavirus, nurses Caroline Quinet (at left) and Yasmina Cheroual rest outside CHU Ambroise Paré hospital. The pair, who had known each other for only a few months, pulled long shifts in the intensive care unit. Like many medical facilities around the world, Belgian hospitals initially were overwhelmed by a rush of patients with the virulent, ever changing new disease. These nurses, pulled from their standard duties, were thrown into full-time COVID-19 work—reinforcement troops for a long, exhausting battle.

THE LITTLE GESTURES

05.09 MOSCOW, RUSSIA “It was shocking inside the hospitals,” said photographer Nanna Heitmann, who documented Moscow under lockdown. At Hospital Number 52, medical staff like this nurse handed out flowers to World War II veterans and other elderly patients to commemorate Victory Day in May. One doctor brought a guitar and serenaded the residents with old Soviet war songs.

OUR NEW WORLD: CONNECTING BY VIDEO

04.03 BOULDER, CO A birthday Zoom call is reflected in Brendan Davis’s glasses, under a foam crown he donned for the celebration. As happy hours, holidays, and work meetings became virtual, “Zoom fatigue” entered our lexicon. Health experts warned that our brains were ill equipped to handle long, emotional, and social-cue-filled interactions online.

A ‘NEW NORMAL’ LUNCHTIME

03.23 WUHAN, CHINA Auto factory workers eat a socially distanced lunch under new restrictions to halt the spread of COVID-19. The virus likely first emerged in November 2019 in Wuhan, a hub of steel and auto manufacturing. A strict curfew was put in place in January 2020. More than two months later, after a drop in daily infections, residents were allowed to slowly restart their lives, though not without careful precautions: Workers, like these employees of Dongfeng Honda, were required to wear masks, undergo temperature checks, and maintain safe distances. “We still need to remind ourselves that as Wuhan is unblocked, we can be pleased, but we must not relax,” People’s Daily, a state-run paper, warned.

A TRIP TO NOWHERE

03.19 PARIS, FRANCE With many flights canceled, the train from the city center to Charles de Gaulle Airport is nearly empty. When stay-at-home orders were issued in mid-March, Paris became one of the first iconic cities to shut down in the face of the coronavirus. William Daniels observed that he had never seen his city so quiet. “One day when I was shooting at the main entrance of Les Halles, one of the biggest commercial malls in Europe, I heard birds singing,” he said. “I’d never realized there were birds at Les Halles of all places. It gave me hope.”

ALONE AND SO FAR FROM HOME

05.21 AMMAN, JORDAN Fatima Mohammad, 37, a Sudanese refugee, stands near her sleeping three-year-old son, Sami. Jordan hosts the second highest number of refugees per capita in the world, after Lebanon. More than 100,000 displaced people live in camps, while 542,700 live in cities and towns. These urban refugees have been hardest hit by the lockdown. Non-Syrian refugees in Jordan aren’t allowed work permits and receive no financial support from Jordan’s government. As a result, refugees from countries such as Sudan, Yemen, and Somalia struggle to eke out a living. The day after this photo was taken, a three-day lockdown was announced to stem the spread of COVID-19, barring nonessential workers from leaving their homes.

ART WITHOUT ITS AUDIENCE

04.25 MILAN, ITALY The figures in Antonio Canova’s 19th-century The Three Graces cling to each other in an empty rotunda of Milan’s Gallerie d’Italia last spring, when Italy’s museums were closed to the public. European museums are reopening slowly, with social distancing rules, temperature checks of visitors, and restrictions on attendees. For small, privately owned attractions, ticket revenue loss poses an existential threat. Up to a tenth of the world’s museums now say they may be forced to permanently close, according to the International Council of Museums.

EMPTY SKIES, EMPTY ROADS

04.25 YOGYAKARTA, INDONESIA One day after a temporary freeze on commercial flights and sea travel, nothing stirred at Yogyakarta International Airport. The new facility in Central Java was built to handle 20 million travelers a year. But less than a month after it formally opened in April, the government announced strict travel restrictions. Travel was halted into and out of Indonesia as COVID-19 spread around the world. The skies were, briefly, vacant. The airport reopened in August with the president’s promise it would be the nation’s busiest, once a COVID-19 vaccine was developed.

A PANDEMIC COULDN’T MASK THE CALLS FOR CHANGE

STANDING UP FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

08.28 WASHINGTON, DC Alem Bekele (left), her sister Herani Bekele (center), and Bayza Anteneh, young professionals from the Washington, D.C., area, stand in front of the Lincoln Memorial during the march on the National Mall in August. “We’re out here because we’re tired of injustice, and we’re here to make a difference for future generations,” said Alem Bekele, echoing the concerns of many protesters. Each of them was involved in D.C. protests last summer. “With the killing of George Floyd, a switch went off. I would log off work early and go to a protest,” Anteneh said. “It lit everybody up.”

DEMANDING JUSTICE

05.31 NEW YORK, NY The protests after George Floyd’s death while in police custody in Minneapolis sparked a global conversation about race, policing, and social justice. Here, a man who goes by the name Royal G stands above a phalanx of police officers at a protest in Brooklyn. “I have a five-year-old daughter … whatever I do today might help her one day,” he said.

A DAYLONG SHOW OF COMMITMENT

08.28 WASHINGTON, DC Fifty-seven years to the day after Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial, another march for civil rights and social justice drew thousands of people to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Organizers dubbed it the Commitment March: “Get Your Knee Off Our Necks,” a reference to George Floyd’s May 25 killing by police. To capture this scene, Stephen Wilkes photographed from a single fixed camera position on an elevated crane, making images at intervals throughout a 16-hour period. He then edited the best moments and blended them seamlessly into one image. Watch a behind-the-scenes video of the making of this photograph.

DEMANDING

JUSTICE

BY RACHEL JONES

Call it the year the world boxed 12 rounds with fear, was left gasping and battered, but won by a decision—the decision to use crisis as fuel.

It was the year the phrase “I can’t breathe” had multiple meanings, from overflowing hospital wards around the globe to deadly interactions on city streets. It morphed from an anguished plea to a battle cry as we squared our shoulders and we rose up.

A dam of anger and grief broke open as the life was squeezed out of a man named George Floyd, sparking a global revolution.

We battled the fear of being too close. Or too disconnected. Some raged at long-standing inequality. Months of confinement ignited the need for escape, not just for recreation but for proclamation.

High school seniors lifted their diplomas and lofted their caps from their front lawns as family and friends drove past, determined to claim public credit for their achievements.

From capital cities to the smallest towns, we reclaimed our voices. We came together in a show of strength in the name of justice. People gathered, most wearing masks as armor against an airborne enemy.

The year yielded profound body blows through the deaths of beloved American icons like Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Congressman John Lewis, who both embodied the country’s fight for equality. We vowed to carry on their work.

The ballot box became a measure of the nation’s appetite for change. In 2020 we fought bare-knuckled for the power to inhale justice and exhale fear.

A MARCH FOR CHANGE

08.28 WASHINGTON, DC Tamaj Bulloch raises his small fist as Alena Battle of Charlotte, North Carolina, holds her son during the “Get Your Knee Off Our Necks” Commitment March on Washington in August. Held on the 57th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the event drew thousands who risked the threat of COVID-19 to demand criminal justice reform and an end to police brutality. Speakers included the son and granddaughter of Martin Luther King, Jr., and relatives of those killed by police.

FOR ‘WE THE PEOPLE’

06.06 WASHINGTON, DC Maria Modlin, 55, from Washington, D.C., was one of thousands of protesters who converged on the White House on the ninth day of protests following the death of George Floyd. “I am so happy to be … part of this great movement. It’s we the people. Not them the people. Now it’s our turn.”

CELEBRATION AS PROTEST

05.30 MINNEAPOLIS, MN Datelle Straub (center) and friends Avery Lewis (left) and Titan Harness-Reed, graduates of Patrick Henry High School in Minneapolis, protested in their graduation caps and gowns following the killing of George Floyd. “Because of COVID we couldn’t walk the stage, so we decided to put our robes on to show that there is Black excellence in our community,” Straub said. When he saw police approaching, Straub lifted his diploma. “As we were walking, cops jumped out of a van and aimed their guns at me and my friends and put a red dot on our chests. It’s just frustrating that they are OK with killing the future.”

‘WE HAVE TO BE OUR OWN SOLUTION’

04.01 NAIROBI, KENYA Musician Daniel Owino Okoth, known as Futwax, sings his song “Have You Sanitized?” with his four-year-old son and apprentice keyboardist, Julian Austin. From his home in Nairobi’s Kibera neighborhood, Futwax wrote and recorded the song to encourage safe health practices during the coronavirus pandemic. “I’m a community leader and icon here, and people listen to my music across Kenya,” he said. “So it’s my duty to make sure that everyone knows what’s happening and are doing what they can to try and stay safe. We have to be our own solution.” Futwax, who walked through town with a megaphone promoting safety, noted that social distancing is not an option for Kibera’s residents. “We share toilets. We share entrances and exits of houses. We share where we iron our clothes after washing. We don’t have supermarkets; we share kiosks. We saw people who were taken away by ambulance, people from the slums who were put into government isolation centers, you know? So I decided to take responsibility in my own hands.”

RECLAIMING THEIR POWER

02.03 WAITANGI, NEW ZEALAND Bronwyn Clifford, 16, stands with other Maori women on New Zealand’s Waitangi Day, which is observed each February to commemorate the Treaty of Waitangi, signed by some 500 Indigenous leaders and the British in 1840. Today Maori youth use social media to mobilize support for the return of ancestral land confiscated during the colonial era and to build momentum for the political partnership between Maori and Europeans envisaged by the treaty.

RALLYING IN SUPPORT OF THE PRESIDENT

11.02 AVOCA, PA The day before the U.S. election, supporters of Donald Trump wait for the president at the Wilkes-Barre/Scranton International Airport in northeastern Pennsylvania. The rally took place not far from the childhood home of Joe Biden, who defeated Trump in the election. “The atmosphere was one of anticipation. It was one of the last rallies and the stakes were really high. People were scanning the sky for his arrival in Air Force One,” photographer Natalie Keyssar said.

HONORING HERITAGE AT THE POLLS

10.31 ORLANDO, FL Barbara Liz Cepeda, 44, of Kissimmee, Florida, leads bomba dancers at an early polling place, entertaining voters as they wait in line. Born in Puerto Rico, Cepeda has lived in Florida for 17 years. The eighth-generation bomba dancer started a dance school to honor her mother, Tata Cepeda, and continue a family legacy. Bomba is an Afro-Puerto Rican dance form developed in that U.S. territory by enslaved people who were brought there from West Africa.

THE POWER OF VOTING

03.12 WASHINGTON, DC Before Howard University student Winter BreeAnne from Riverside, California, was eligible to vote, she developed a program to help young people understand that voting matters. “That’s how we elect the people who represent us,” she said. “If we aren’t voicing our opinion that way, when we have the ability and not everybody is afforded that right, we are relinquishing a lot of political power.”

INSPIRATION, NOW

11.07 WILMINGTON, DE “Our country has sent you a clear message: Dream with ambition,” Kamala Harris said, as she and Joe Biden gave victory speeches. Dressed in white to honor women suffragists, she became the first woman, first Black person, and first Asian American to win the vice presidency. “Every little girl watching tonight sees that this is a country of possibilities.”

THE YEAR THAT HOPE ENDURED

AMID TRAGEDY, WE FOUND NEW WAYS TO LIVE, THINK, AND HEAL

RELISHING NATURE

04.06 JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA Flowers brighten a barbed wire fence in a Johannesburg township. People here often don’t have space for gardens, but they find beauty in unexpected places, says Lindokuhle Sobekwa. “Growing up, there were always some flowers that grew near a dumping site, that we used to pick and play with.”

A MILESTONE LAUNCH FOR U.S. ASTRONAUTS

05.30 KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FL The SpaceX Crew Dragon lifts off for the International Space Station (ISS), launching a new era of spaceflight in which “more space is going to be available to more people,” said NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine. Strapped inside were Robert Behnken and Douglas Hurley, the first astronauts to launch from U.S. soil since the last space shuttle in 2011—and the first to fly on a SpaceX mission, part of a new commercial space program. “We’ve longed to be a part of a test mission,” said Behnken. “It’s something we maybe dreamed about.”

… AND A HISTORIC WALK IN SPACE

07.21 INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION Some seven weeks into his stint aboard the ISS, Behnken (at left) and Chris Cassidy exited the station to conduct a space walk to install a toolbox for a Canadian Space Agency robot and perform other maintenance tasks. The five-and-a-half-hour exercise marked the 10th space walk for the veteran astronauts and the 300th by Americans. Hurley, Behnken’s partner on the Crew Dragon, snapped their photo from inside the ISS. Twelve days later, Behnken and Hurley ended their mission with a splashdown in the Gulf of Mexico.

RENEWING HOPE

BY RACHEL HARTIGAN

“Sing a song, full of the hope that the present has brought us.” James Weldon Johnson wrote those words for “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” known as the Black national anthem, toward the end of the 19th century in Florida—a state that then had one of the highest rates of lynchings and where most Black men could not vote. Yet he found reasons to hope. We can too—and we have.

We found hope in the doctors and nurses who worked beyond endurance to save lives. We found hope in learning new ways to connect with loved ones. We found hope in the extraordinary developments—the scientific discoveries, the conservation victories, the social awakening—that occurred amid the pandemic and natural disasters. And we’ve found hope in the change that this year of calamity might bring.

“There will be a renewal of optimism in a better world that we know is possible,” Sylvia Earle, the legendary oceanographer, said in August shortly before her 85th birthday. “That we can, through our individual and collective actions, turn to a new era of respect for the natural systems that keep us alive, and for one another.”

We’re already seeing positive change. “Just like in wartime, we’ve moved quickly and tried new things,” Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates said in an interview with Editor in Chief Susan Goldberg, citing six promising COVID-19 vaccines in the works.

As wrenching as the turmoil has been, it’s forcing people across all walks of life “to assess whether we are where we need to be,” Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza said over the summer, “and what we need to do to get to where we’re trying to go.” There’s still hope that we’ll get there.

DISCOVERING VIRUSES THAT DO US GOOD

09.23 PALO ALTO, CA Not all viruses lead to global pandemics. Some have evolved to our benefit. An ancient virus called HERV-K may protect human embryos from other viruses, according to Joanna Wysocka, a professor of both chemical and systems biology and of developmental biology at Stanford University. When an embryo reaches the eight-cell stage (as projected here), HERV-K is activated and may nudge the cells to build proteins that shield them from infection. It turns off when the embryo implants in the uterus. Ancient viruses make up nearly 8 percent of human DNA, with HERV-K joining an ancestor’s genome more than 30 million years ago. Scientists like Wysocka are continuing to untangle how viruses have become a part of us.

A DAM IS REMOVED, AND A RIVER REVIVES

05.28 WESTBROOK, ME Alewives—a kind of river herring about 10 inches long—crowd Mill Brook on their way to spawn in Highland Lake, near Portland, Maine. Alewives are anadromous fish—they live in the ocean but migrate to freshwater to reproduce. Yet for more than 250 years, alewives and other migratory fish found their passage to the lake blocked by a dam on the Presumpscot River. In 2002 the dam was removed. Hoping to restore the migratory life cycle to the river system, biologists stocked Highland Lake with the fish. The alewives made their way from lake to brook to river to ocean and back again. The run of alewives has increased every year since and now numbers more than 60,000 fish. Their resurgence benefits other creatures as well: Seals and whales, eagles and ospreys, mink and skunks all feast on alewives. People enjoy them too. Six miles of Mill Brook are now protected with streamside trails, which in late spring are filled with visitors eager to catch a glimpse of the resilient alewives.

WILDLIFE PERSEVERES

09.18 MARA RIVER, KENYA Every year more than a million wildebeests rumble north across the Serengeti in a migration that is one of the world’s great spectacles. In 2020 it was no different. Herds followed seasonal rain from northern Tanzania to Kenya’s Masai Mara. During one summer sunset several thousand wildebeests gathered at the edge of the Mara River and spilled down its banks. Crocodiles awaited them in the water and hyenas on the other side of the river. Fresh green grass did too, and so they pushed forward, as they always do.

PROTECTING A WONDER OF NATURE

06.11 EMPIRE, MI As the sun sets, a curtain of rain descends from storm clouds near Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore on the northeastern shore of Lake Michigan. Far to the south, the city of Chicago has begun one of the world’s largest civil engineering projects, a massive tunnel and reservoir system to prevent raw sewage from discharging into the lake. The five Great Lakes contain more than a fifth of all the surface freshwater on Earth, and their shores, shaped by glaciers, have hosted humans for thousands of years.

SLOWING THE SPREAD

04.14 SEOUL, SOUTH KOREA At the H Plus Yangji Hospital in Seoul, a walk-in testing clinic is set up like a row of phone booths to prevent contact between patients and medical staff. Nose and mouth swabs take less than three minutes, and test results can be returned in four to six hours. Experience with previous disease outbreaks prepared South Korea for the COVID-19 pandemic. The country already had a legal framework for contact tracing, and most residents stayed home and wore masks in public. The government worked with the private sector to swiftly ramp up testing. There are hundreds of testing sites throughout the country.

COVID-19 TREATMENTS ARE GETTING BETTER

05.09 MOSCOW, RUSSIA One of the most helpful therapies for COVID-19 is one of the simplest: turning patients, such as this intensive care patient in Moscow, onto their stomachs, which improves the lungs’ ability to get oxygen into the blood. Nearly a year into the pandemic, doctors are getting a handle on which medications and techniques best treat the disease. They’ve learned that the antiviral remdesivir shortens recovery time, while the steroid dexamethasone cuts the risk of death by a third in patients requiring ventilation.

THERE IS NEW LIFE

04.29 NEW YORK, NY At the height of the pandemic in New York City, Kimberly Bonsignore learned that the hospital where she planned to give birth wasn’t allowing family members inside. She chose to have her baby at home, with her husband and toddler—and midwife Cara Muhlhahn and doula Angelique Clarke to help. Clarke set up a birthing pool in the family’s living room and texted Muhlhahn when Bonsignore’s water broke. In less than two hours, Suzette was born. The baby was unresponsive at first, but when Muhlhahn performed CPR, the newborn let out a wail. Moments later, they all heard the nightly sound of New Yorkers clapping to show their appreciation for first responders.

IN LOCKDOWN, A CHANCE TO GET CLOSE

03.30 KUALA LUMPUR, MALAYSIA Photographer Ian Teh spends much of his working life on the road. The pandemic allowed him to stay home with his wife, Chloe Lim, in Kuala Lumpur. “My partner and I are lucky that both our families are safe,” he says. “The pandemic has been an opportunity for us to connect with our loved ones, virtually.” One day he took a self-portrait: “We are sitting by our favorite spot in our apartment, looking out to the nearby houses and greenery. It’s peaceful.”

TIME TOGETHER

03.25 SANTIAGO, CHILE A self-portrait shows Tamara Merino with her son, Ikal, during their first week of quarantine. “An unexpected joy is that I have been spending 24/7 with my baby, and that is priceless,” says Merino. Her mother is also with her. “It is an endless circle, since she is the beginning of my own motherhood. And today we are sharing experiences that we would never have lived together if it weren’t for the isolation.”

KEEPING IN TOUCH WITH FRIENDS

04.06 SANTA ROSA, CA Whether through Zoom happy hours, backyard gatherings, or socially distanced walks, people have found ways during the pandemic to connect with the people they care about. “My daughter, Catalina, misses her friends very much, so we did the rounds in our car and visited her best friends from far away,” says Alessandra Sanguinetti. “Here she’s breaking the rules and touching fingertips with her best friend, Avery.”

A HUMAN TOUCH, WRAPPED IN PLASTIC

05.24 WANTAGH, NY After more than two months of social distancing, Mary Grace Sileo (at left), her daughter, Michelle Grant, and other family members found a way to safely touch their loved ones. They hung a clothesline in Sileo’s yard and pinned a drop cloth to it. With one on each side, they embraced through the plastic.

A FAMILY’S FAREWELL

04.25 DETROIT, MI Jerry Lovett releases a dove to symbolize his brother Chester’s spirit. A retired Detroit mail carrier with 10 children, Chester died of COVID-19 complications. Under pandemic rules, only 10 people at a time could attend his funeral, but some of his family members were able to gather outside to watch the dove take flight.

See more of 2020’s best photography, including discoveries, animals, travel, and moments we’ll never forget.

- “UN inquiry finds Russia’s deportations of 20,000 Ukrainian children amounts to crimes against humanity “, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Reuters

- “Brooks and Capehart on Trump’s decision to launch strikes on Iran”, PBS NewsHour

- Issue of the Week: War

- “The Original”, The New Yorker

- “Big Change Seems Certain in Iran. What Kind Is the Question”, The New York Times

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017