A thesis that informs my argument is the belief that the certainty of death, and our efforts to resist and postpone it, are what permit meaning in life. It follows from this thesis that obscuring our relation to this certainty obscures the true stakes and significance of living. The parents who believe that it should not be their child who fights in a war, or their child who forgoes some special advantage, or their child who opts out of today’s careerism at the call of conscience, is no different from the politician or pundit who tells us we cannot “afford” to act on climate change. Generalized and applied to society at large, these self-exempting principles make us weaker, poorer, and more likely to die. For fear of death, they teach us, we cannot afford to protect life.

In the same way, by paying rhetorical homage only to the suffering that climate violence is sure to bring, and neglecting, as perhaps in bad taste, the potential promise in a fight we can’t avoid, we perpetuate a form of the dishonesty that got us here. This is the belief that how we talk about something—whether guided by ideological or moralistic convictions—affects its underlying reality: that by insistence we can freight the unconscious world with our moral schemas. But nature is dispassionate, and we are not being punished. No amount of atonement or misgiving makes any difference. We have a practical crisis on our hands, and it is the first truly universal project in which all of us—all living things—are on the same side.

One promise in this fight—if we address it with the pragmatic clarity one needs in a war—is that it will force us to learn exactly how we relate to the world beyond us and how irrelevant the ego’s preferred myths are to achieving anything tangible. At its best, war has been a tonic that disabuses such idle myths: simplistic equations, for example, about how competitiveness, self-reliance, and self-gratification redound to prosperity, strength, and happiness. Nowhere does war root out more misguided thinking than in the realm of economics, since of all the things whose costs we are told we can’t afford, the expensive diversion of human and industrial capacity to the project of explicit destruction would seem to be first in its class. But going to war rests on the argument that forgoing its expense would be more costly still.

In this way, war helps put the economics of fighting climate change in perspective. It reminds us that words such as “cost” and “afford,” when applied to society as a whole, do not describe objective conditions but rather implicit arguments about how we should expend our energy and resources: which activities and investments today are going to be worth it in the long run.

The preservation of life would seem to be a no-brainer, yet even in the years leading up to America’s entrance into World War II, when the threat posed by a fully mobilized Germany and Japan was clear, the Roosevelt Administration had trouble securing the modest appropriations it sought. Members of Congress, pundits, and other political figures inveighed against the cost and practical impossibility of the war mobilization. When Roosevelt announced that he would like to see the nation producing fifty thousand warplanes a year, Charles Lindbergh dismissed the figure as “hysterical chatter.” To many, he had a point. According to Arthur Herman’s book Freedom’s Forge, aircraft manufacturers in 1938 were supplying the U.S. military with only about ninety planes a month.

Across virtually every industry, as Herman’s book details, the intended expansion of military capacity and the time frame expected to achieve it appeared impossible, and yet, despite all manner of opposition, naysaying, and bureaucratic headwind, the targets were routinely met and exceeded. The production of tanks, in one instance, went from thirteen to more than a thousand per month. Mammoth shipbuilding endeavors sprang up in mudflats and marshes, and new industries, such as synthetic rubber, went from producing virtually nothing to hundreds of thousands of tons of material. The vast majority of these initiatives ratcheted up to full capacity in only eighteen months.

Herman tells the story of how the private and public sectors worked together through the war years to create an “arsenal of democracy.” In three years, beginning effectively from a standing start, the industrial capacity of the nation would overtake that of the Axis powers and go on to produce two thirds of all the military equipment used by the Allies. The war created more than half a million new American businesses, Herman writes, while simultaneously jolting thousands of existing businesses out of the doldrums of the Depression.

The ultimate outlay required of the United States would top $300 billion. Consider that in 1939, U.S. defense spending eclipsed $1 billion for the first time since 1918. The difficulty in funding the mobilization reflected the belief among politicians that such expenditures could not be afforded, or else, after a decade-long depression, could be put to better use. But this wartime spending—deficit spending that as a percentage of GDP exceeded anything before or since—underwrote a booming economy that grew, for certain years of the war, in excess of 17 percent and nearly doubled from the start of the war to its end. Not only did the United States emerge from the war anything but crippled with debt—the growth and shared prosperity the country experienced in the subsequent decades would prove unparalleled.

No one, looking back, would say that the need to confront Germany and Japan did not justify the immense redeployment of resources. The same logic of downside risk applies every bit as much to climate violence. But the larger point is that we emerged from the war years not just better off because a dangerous enemy had been defeated, but better off in absolute terms.

This should give pause to critics of climate action who continue to invoke its cost. It is hard to see how a revolution in technologies that promise limitless clean energy could fail to underwrite the next chapter of human prosperity. Wartime research and development returned extraordinary dividends in postwar technologies, and consistently high spending on forward-looking research during the Cold War repaid the investment handsomely, resulting in the internet, satellites, cell phones, and GPS technology. Clean energy would be no different.

These are the benefits: revolutionary technologies, new industries and jobs, an industrial age founded on the promise of meaningful work. What happens if we consider the cost of inaction?

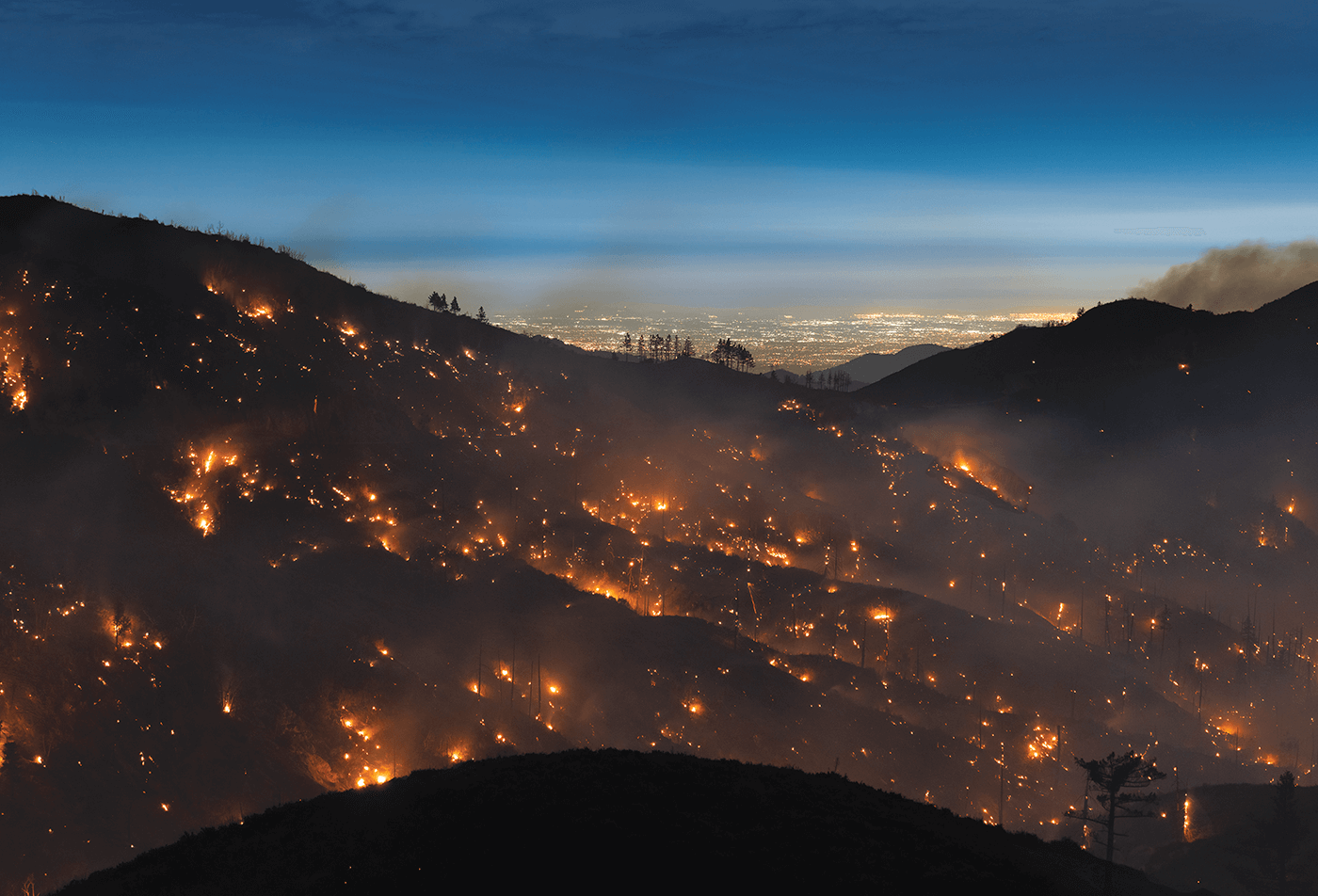

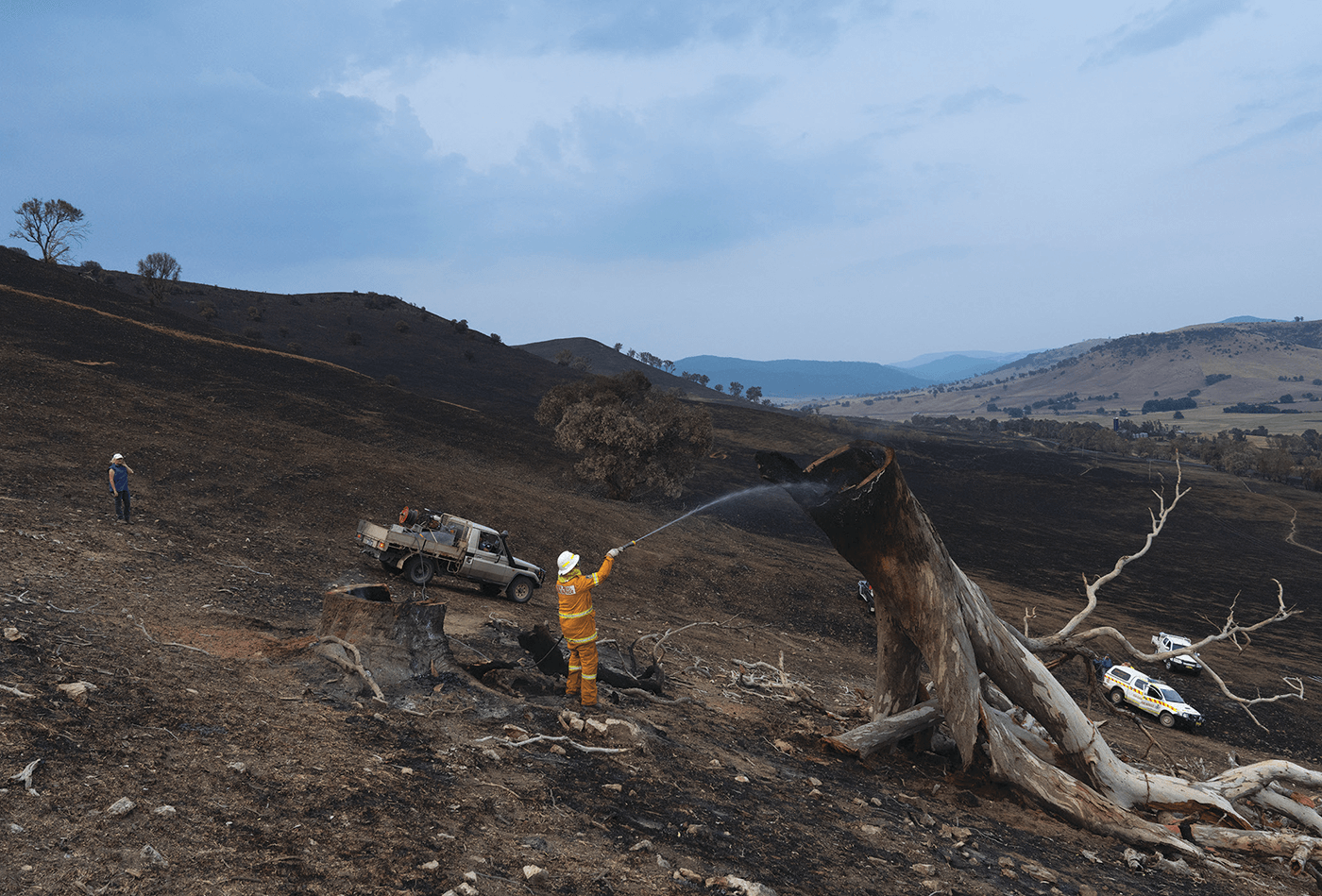

The price of a warming planet is hard to quantify precisely, since it involves accounting for compounding factors and assigning monetary value to human life. Nonetheless, even conservative estimates are high, cleaving whole percentage points and hundreds of billions of dollars from annual growth. One study concluded that the costs associated with 3.7 degrees of warming—extreme heat, drought, water stress, flooding, reductions in crop yield, increased exposure to malaria and dengue fever, and sea-level rise—would be $551 trillion worldwide. That is substantially more than the global wealth that currently exists. The 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, California, affected a large but fairly sparsely populated area (0.006 percent of total U.S. land) and still managed to cause more than $16 billion in damage, twice the annual budget of the EPA.

Regardless of how one estimates the financial burden of massive refugee flows, failing cropland, lost coastline, disease, and crippling storms, the cost of taking mitigating steps today pales in comparison. The current price of insurance, in other words, is cheap. The problem is that no person, company, or nation can take out a policy on its own. We have to go in on it together or it won’t work.

How expensive is too expensive? When we are talking about deaths in the hundreds of millions and damages in the trillions, one could argue that there is no price too great. It takes capital to plant crops in the spring, after all, but there is no price at which we could afford not to produce food. Having a habitable planet is no different, and what we avoid paying today, with claims that we can’t afford it, may make the future wholly unaffordable, no matter how much we have saved.

Consider drinking water. In many countries water is currently plentiful and cheap. But if water grew scarce, there is no limit to how expensive it could become, since without water a person quickly dies. At a certain degree of scarcity, there is no price you can pay for water, since it is in no one’s interest to sell. Likewise, if grain became scarce enough, a wheelbarrow of cash would be insufficient to buy a loaf of bread. What does it mean, then, to have saved money years before?

The way we talk about saving and spending leaves out the fact that what people and countries save and spend today affects the availability of things in the future. As we all know, the ultimate supplier of everything we use is the planet, and the earth cannot be bribed or cajoled at any price. Money means nothing to it, since it knows money isn’t real.

The more climate change turns the earth into a desert island, the more we will learn that wealth can be lost, permanently. It does not conserve itself like energy or momentum, and it cannot always be turned into the things we want if the things we want are too hard to come by. Humans are ingenious and adaptable, but they aren’t magicians: They can’t reap, mine, or harvest what doesn’t exist. If our foundation corrodes—if it falls away into the sea—we will simply lose all the wealth it props up, hoarding gold coins and paper bills until that is all we have left to build with, write on, eat, and drink.