“Lessons for South Africa from the global insurrection playbook”, Daily Maverick

By J Brooks Spector, Age of Anarchy, Johannesburg, 15 July 2021

The ongoing civil disorder and looting in SA encourages us to look at other relevant riots, looting, protests, and insurrections around the world. What are the underlying similarities and what lessons might be drawn from those examples?

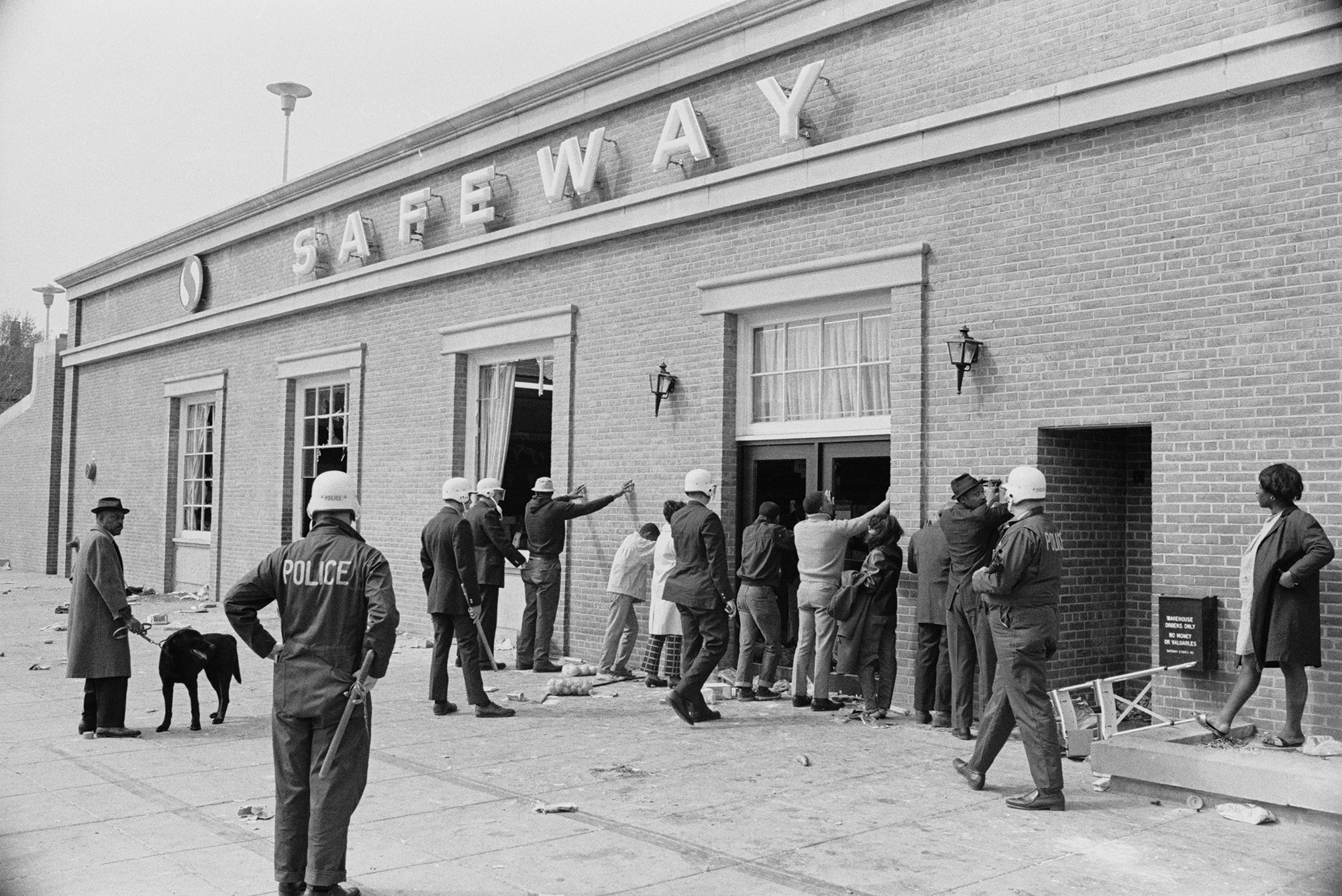

The army is called out during riots in Washington, DC, following the assassination of civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. (Photo: Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images)

The current national trauma South Africans are experiencing encourages us to try to look deeper to understand the nature of social insurrection. Where does it come from, how does it take hold, and how does it finally end? And perhaps the best place to start is with the personal.

On 4 April 1968, US civil rights leader the Rev Martin Luther King Jr was killed while he was standing on the balcony of his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. He had gone to Memphis to support a strike by municipal rubbish collectors. But he was also trying to reignite his role as first among equals in the civil rights struggle. His visit to Memphis was thus also in response to challenges from younger activists whose significantly black power-driven agendas often differed from King’s more universalist posture.

Regardless of any rivalries, King’s death set off a wave of both anger and despair among – but not limited to – African Americans. But more than such understandable emotions, it also triggered arson, looting, and robbery in or near predominately black neighbourhoods, in cities across the country, including the national capital.

In Washington, DC, the police were initially overwhelmed in efforts to control the violence as whole streets of retail businesses were wiped out. Soon enough, National Guard units were called up to help restore public order, and then, eventually even regular army units were deployed, including a detachment stationed at the Capitol building.

The front pages of the nation’s newspapers showed soldiers, complete with a machine gun or two at the ready, manning a barricade of sandbags. Soon enough too, even as the fires of looted stores were still burning, other military detachments were stationed on major roads in and out of the city, and vehicles on those roads were stopped, the people in them were questioned, and the vehicle was searched – presumably for weapons or petrol in containers.

In the midst of this chaos, there I was, together with several other university debate squad members, travelling in my old, banged up Volkswagen, as we rode to the venerable Willard Hotel, located just down the street from the White House. The hotel hosted the opening night dinner and keynote speech for the national university debate tournament we were participating in. The tournament was obviously being held under more stringent security arrangements than are usual for such an event, but things seemed reasonably calm inside the hotel, despite the ongoing problems just outside. Later in the evening, though, as we were leaving, we heard police sirens wailing as those vehicles were speeding to another outbreak of violence or looting.

As we left the hotel, driving up 16th Street, the major north/south thoroughfare in Washington, DC, that begins at the White House towards our university, we proceeded very cautiously. Suddenly, from the semi-darkness, there were signal lanterns and then abrupt orders: “Stop, turn off your engine. Identify yourselves. What are you doing and where are you going?” One lesson from this moment was: you don’t argue with soldiers when they are holding their weapons at the ready, giving you a fishy eye.

Ultimately, of course, the republic stood, and even those sustained riots proved not to be an existential threat to the government. But they did terrible damage to whole retail streets in many cities as the business owners fled to safer areas, or simply ceased trading entirely. What had happened in those days, moreover, was a consequence of decades – even centuries – of failed promise to the African American population on employment, education, and social and political equality, despite continuing the process of sweeping away legalised inequality with measures like the 1964 and 1965 Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. It just required one incident to set things in motion.

A week or so later, I was at “ground zero” of the damage. I was there to research and then write a student magazine article about the “Poor Peoples’ Campaign” encampment on the Mall (the vast greensward that stretches from the Capitol on through to the Lincoln Memorial) that had still gone ahead, despite the death of its initiator, King. At the intersection of 14th and U streets NW, I was seeking an interview with the campaign’s organisers, before going to the actual encampment, designed to protest poverty and racism. 14th Street had been a busy commercial area, but now it was lined with burnt-out stores, and the smell of devastation lingered on. It actually took decades before the street returned to something approaching its former health, although by then the process of gentrification had changed the demographics of the entire neighbourhood.

Soon enough, for many, this anger and despair coming out of King’s death increasingly was merging with the larger national distress over the growing US military involvement in Vietnam that required the drafting of thousands of young men for military training – a disproportionate number of whom turned out to be African Americans – and then the cauldron of Vietnam.

While it is true this rebellion from below never truly threatened the national government, it became yet another wound to the administration of President Lyndon Johnson. The sad irony of the times was that a fear on the part of many white Americans that there might yet be worse to come out of the black community then helped generate support for Richard Nixon in the 1968 presidential election. That victory then guaranteed four more years of US fighting in Vietnam – and many years more of sweeping that black anger back under the rug.

But for this impressionable university student, April 1968 ensured I began to understand that governments are not inevitably stable. And citizens can become so angry – in ways they may not even be able to explain calmly – they will destroy the very enterprises they depend on for their daily lives in their own neighbourhoods. That should be a lesson for those of us in South Africa watching events here, now. A bit further along, we will also take a look at a newer civil insurrection in the US. That, of course, is the one that culminated in the 6 January attack on the Capitol building.

Six years after the rioting and looting in Washington, in 1974, I found myself in Jakarta, Indonesia, now a newly-minted foreign service officer, working in my first overseas assignment. Just a few years earlier, Indonesia had been rid of that economically disastrous, dangerously performative politics of President Sukarno. He had kept his country in the world’s headlines as he threatened neighbouring Malaysia and the Philippines, and railed against the two neo-imperialist, neo-colonialist nations, the US and Britain.

Now leading the country was another mono-monikered leader, General Suharto, who, amidst the Byzantine politics of Indonesia, had survived an initial coup attempt, then led a counter-coup, and eventually taken full control of the nation, reversing the political and economic orientations of the national polity. Gingerly embracing former enemies, Suharto openly encouraged foreign investment, joined regional international associations, and followed a pathway towards economic growth endorsed by international financial and economic organisations (although levels of corruption grew as more and more money flowed into the country).

But the growing presence of Japanese and other investors in major industrial and commercial projects began to rankle many. The glitter of the top tier’s lives, and especially the corruption of officials who seemed connected to the growing investment was a glaring irritant as the country’s poor seemed unable to benefit from the boom times.

Potentially dangerous for national stability, much of this growth was taking place, hand-in-hand, with key elements of the resident Chinese community, many of whose families had lived in Indonesia for generations, but for many ethnic Indonesians still remained an alien presence. It was probably only a matter of time before antagonisms within the ruling elite (perhaps over divisions of the spoils) melded with the larger economic discontents in the country. There was inevitably, too, rising anger about youth unemployment. Some of that should sound disturbingly familiar to South African readers.

In the days leading up to the explosion, newspapers had been pointing to the corruption and connivances, and in early January 1974, a rebellion against the ruling elite, the resident Chinese, and their foreign investor allies broke out. Anyone driving a Japanese-made or branded vehicle was pulled out of it, the vehicle was unceremoniously destroyed, and then those mobs moved on to shopping malls where the majority of stores were owned by local Chinese merchants. The malls were looted, the buildings were burnt, and it seemed inevitable that a much larger revolt was about to break out – that is until elite military units were sent out into the streets to confront the mobs and attempt to bring the disorder to a sullen end.

For this young officer, it was a sobering experience to escort a senior Washington official from his hotel where a mob’s confrontation with the army was just a few hundred metres away, complete with tear gas, stun grenades, and, eventually, live ammunition. With trepidation, we made our way to the home of a senior embassy staffer for a working lunch where some invited guests had suddenly been detained for questioning, while those who had made it had had to negotiate their way past tanks blocking a nearby intersection and troops manning barricades.

So here was another lesson learned. It is not inevitable that rapid economic growth means people will embrace the government because of that growth – if many believe the fruits of that growth are going to a predatory elite and their, ulp, foreigners. Instead, that growth can mean support for the government, and its legitimacy can disintegrate under pressure.

Earlier this year, on 6 January, an insurrection broke out in the US. It came at the culmination of angry feelings of loss of status versus minority ethnic and racial groups and over longer-term economic trends that have drained jobs from their states, a deep dislike of what they believed was their disparagement by the better educated, and a fear their interests no longer mattered. It exploded at the instigation of politicians – especially by the then-president – that they must take back “their” nation. As a result, a violent mob insurrection tried, and nearly succeeded, in overrunning the national legislature’s deeply symbolic headquarters. The continuing public strong presence of such beliefs delivers yet another lesson. This one is that a government may comprise many different strands of ideas, but unprincipled leaders, especially fake populist rabble-rousers, can easily find ways to exploit such beliefs for their own benefit, despite harms to the larger society.

Then, just the other day, we discovered that Cuba has begun to learn such lessons – and some others – as well. With the island now ruled by an increasingly sclerotic Communist Party, but with its first non-Castro-named president since 1960, it has now entered an increasingly treacherous economic landscape. The disappointing level of sugar exports, its leading agricultural commodity, and the collapse of the international tourist industry because of Covid restrictions on travel have been particularly devastating. (Yes, a US economic embargo has contributed to the country’s general economic circumstances, but that policy cannot easily be blamed for the current severe downturn as it has been policy in various ways for more than half a century.)

Growing shortages of food, fuel, electricity, and even piped water have further bothered people in the course of their daily lives, even if changes in government policy over the past few years had begun to allow individuals to run small, independent businesses. (Of course, businesses dependent on the tourist stream with their forex earnings have been devastated as the cruise ships are simply not arriving.) Even stores selling otherwise scarce foods and only accepting payment in foreign exchange have shortages now. As a result, a growing sense of popular dissatisfaction, albeit one with no leaders or obvious organisers, has sprung up, as chances for improving economic opportunities now seem thwarted by a government unable to solve these problems.

One other factor, however, deserves mention as well: 3G mobile phone technology has now become accessible for many Cubans, thereby allowing social media messages of support or encouragement for protests to circulate well beyond government control, as long as the network is still operating. This phenomena is new for Cuba, even though the power of mobilisations via social media first came into view two decades ago when opponents of an incumbent Philippine president were able to summon vast crowds for rallies by sending SMSes to supporters, asking initial recipients to send the message on to others, generating exponential growth in the number of transmissions – and eventually triggering the resignation of that president.

Rallies of crowds of people opposing the Cuban government sprang up in cities and towns across the country in a spontaneous efflorescence that seems to have stunned the government. In the aftermath of those initial rallies, the government sent out police units to arrest the presumed ringleaders, they clamped down on social media generally, and, inevitably, they blamed US agents provocateur for the events, even if US government sources seem to have been about as surprised by the events as the Cuban government was.

In this, there are echoes of the “Arab Spring”. Right up to the end of 2010, analysts had argued that civil upheavals were probably inevitable in the Arab world, but virtually no one expected that the suicide of a despondent fruit and vegetable vendor would be the spark that ignited it all, from to the Syrian civil war, to the removal of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and then much else across the region.

And so, in this, there is yet another lesson. This is where we recognise that communications can easily be the ultimate disrupting factor affecting weak, incompetent, or authoritarian regimes attempting to reform or respond in some way to growing economic and civil distress and tensions.

And so, finally, we circle back to South Africa, even as its current convulsions are ongoing. Commentators and analysts point to a whole roster of underlying causes for the country’s desperate circumstances, as well as identifying precipitating causes that have led to the looting. In fact, all the lessons from these case studies seem to apply, combined with the trigger of the political crisis arising from the incarceration of the former president, along with all the actors who hope to exploit his arrest.

But then there are the underlying angers and despairs in a population increasingly affected by the nation’s poor economic circumstances (together with the paralysing impact of the Covid-19 pandemic), the real sense of grievance over the unequal distribution of economic benefits, and the impact of a communications revolution that allows virtually instantaneous communication between people without regard for distance, and among large numbers of people powered by the growing access of cellphones. (Some estimates say there are more cellphones than people in the country at this point.)

The real question, then, is not why this has happened in South Africa, now in July 2021. Rather, the right question is why anyone could have believed the country was not precariously poised near the lip of a caldera, and that it might only take one politically potent event to light the fuse of a national calamity. This calamity will reverberate for days, weeks, months, and years to come. There will be continuing political, economic, and social aftershocks. And it will likely cause a deep crack in the country’s already foundering international reputation. DM

J Brooks Spector

Spector settled in Johannesburg after a career as a US diplomat in Africa and East Asia. He has taught at the U. of the Witwatersrand, been a consultant for an international NGO, run a famous Johannesburg theatre and remains on its board, and been a commentator for South African and international print/broadcast/online media, in addition to writing for The Daily Maverick from day one. Post-retirement, Spector has also been a Bradlow Fellow of the SA Institute of International Affairs and a Writing Fellow of the University of Johannesburg’s Institute for Advanced Studies. Only half humourously, he says he learned everything he needs to know about politics from ‘Casablanca.’ Maybe he’s increasingly cynical about some things, but a late Beethoven string quartet, John Coltrane’s music, and a dish of soto ayam (one of Indonesia’s great culinary discoveries) will bring him close to tears.