Issue of the Week: War

The lost tablet and the secret documents, BBC News, 11 August 2021

Much of what goes on in the world–in wars, crimes against humanity, nationalism, classism, tribalism, racism, sexism and all the fights for power by those who seek to have it or keep it over the majority of people at the expense of their basic needs and human rights–is shadowy.

The BBC News Long Read, The lost tablet and the secret documents, publshed today (8.11.21 in London) is an incredible investigative piece. If you want a look at how the world works where you can’t see it, here it is:

The lost tablet and the secret documents

By Nader Ibrahim in London and Ilya Barabanov in Moscow, 11 August 2021, BBC News Arabic and BBC News Russian

Clues pointing to a shadowy Russian army

Wagner is a Russian mercenary group whose operations have spanned the globe, from front-line fighting in Syria to guarding diamond mines in the Central African Republic. But it is notoriously secretive and, as such, difficult to scrutinise.

Now, the BBC has gained exclusive access to an electronic tablet left behind on a battlefield in Libya by a Wagner fighter, giving an unprecedented insight into how these operatives work.

And another clue given to us in Tripoli – a “shopping list” for state-of-the-art military equipment – suggests Wagner has probably been supported at the highest level despite the Russian government’s consistent denials that the organisation has any links to the state.

It was late one night in early February when I received the call in London. It was one of my contacts in Libya with some extraordinary news – a Samsung tablet had been retrieved from a battlefield in western Libya.

Russian mercenaries had been fighting there in support of Libyan renegade general Khalifa Haftar, against the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA). It’s believed the tablet had been left behind when the fighters retreated in the spring of 2020.

There had long been reports that Wagner had been operating in Libya. This surveillance footage, filmed by GNA fighters in December 2019 and shared with the BBC, is believed to show Wagner fighters.

But we had little direct information. The Wagner group is one of the most secretive organisations in Russia. Officially, it doesn’t exist – serving as a mercenary is against Russian and international law. But up to 10,000 operatives are believed to have taken at least one contract with Wagner over the past seven years.

After various verification processes, a BBC team brought the tablet to London. I immediately put it in a signal-blocking bag, so it couldn’t be tracked or wiped remotely.

Remarkably, the information on it was easy to access. I discovered dozens of files – ranging from manuals for anti-personnel mines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), to reconnaissance drone footage. A number of books had been uploaded – including Mein Kampf, A Game of Thrones, and a guide to making wine.

But it was a maps app that stood out – layers of military maps of the front line, all marked in Russian. Most of the location dots were clustered in the suburb of Ain Zara in south Tripoli, where Wagner fighters had battled with the GNA between February and the end of May 2020.

The maps corresponded with drone footage of Ain Zara, also on the tablet. The video showed the suburb deserted – its residents having fled.

Looking through the files and apps on the tablet, there is nothing to identify the owner – but zooming in closer on the maps, words can be seen written next to some of the red dots.

My BBC colleague Ilya – who has been investigating Wagner for the past four years from Moscow – realised they were codenames, possibly comrades of the tablet’s owner. Ilya cross-referenced them with a database of Wagner fighters set up by Ukrainian volunteers, and a leaked UN report listing Wagner fighters in Libya.

We believe one of the fighters – labelled ‘Metla’ on the tablet – is a 36-year-old Russian called Fedor Metelkin from the North Caucasus.

His personal Wagner number, published on the Ukrainian database, is below 3,000. This suggests he joined Wagner fairly early in its operations – five or six years ago – when it was fighting in eastern Ukraine in support of Russia-backed separatists. From what we understand, it’s usual for the same fighters to move from one foreign conflict zone to another.

The tablet does not give clues about the identity of other mercenaries, but the BBC has since gained rare access to two former Wagner fighters – on condition of anonymity – who confirmed that many of those who started out in Ukraine went to oil-rich Libya.

One told the BBC that there were as many as 1,000 fighters in Libya at any one time over the 12-14 months of active fighting in the country from September 2019 to July 2020.

The former fighters explained that men are not recruited to an organisation called Wagner, but instead apply for short-term contracts – for example as oil rig workers or security personnel – with numerous shell companies.

Watch: Haftar’s Russian Mercenaries: Inside the Wagner Group

They undergo physical tests and background security checks before moving to Wagner’s unofficial training ground near Krasnodar in southern Russia, which is next to a Russian army base.

They are then sent abroad, on the understanding that if they are killed, Wagner may not be able to repatriate their bodies.

One ex-fighter stressed that both the organisation and individual fighters are motivated by financial gain. The BBC understands that most of the men come from small towns, far away from major cities, where employment opportunities are scarce.

They can make up to 10 times the average salary by signing up with Wagner, one of the former fighters said, describing his ex-comrades as “modern-day Vikings”.

“Whenever there is some kind of armed conflict somewhere, Wagner soldiers talk about it. ‘We could go to this one, that could be one for us.’ Because every contract and every country is money. If you don’t have a contract you sit there in reserve with no money.”

He said many Wagner operatives – including himself – have a criminal record, making it hard for them to join the regular army.

There is little doubt they kill prisoners – something he freely admits.

“No-one wants an extra mouth to feed.”

The other former fighter told us the organisation does not issue any code of conduct for its operatives.

In the Libyan village of Espiaa – which is marked on the tablet’s maps as a Wagner position – we met a man who told us that three members of his family were killed by men speaking Russian.

The murders are being actively investigated as a war crime, according to Libyan military prosecutor Mohammed Gharouda, who works for the country’s ministry of defence.

The village is 45km (30 miles) south of Tripoli, and when we visited in April this year the man – who we are not naming – related what happened on the afternoon of 23 September 2019.

He said he met an armed group on the road, who started shooting into the air. He was followed back to his father’s house, and six or seven foreigners forced their way in. He and his relatives were searched, and then were driven to Qasr bin Ghashir, about a 20-minute drive away.

According to the GNA, Qasr bin Ghashir was a Wagner base at the time. The man said he and his relatives were blindfolded, and their hands were tied. They were driven around in a truck for several hours before arriving back that night at a farm in Espiaa.

At around six in the morning, he said, they were taken to a small outhouse in the village. Some of the men then climbed back in the car, but two remained outside the outhouse armed with Kalashnikovs.

“One of them took [out] his weapon,” he said. “At this moment I understood. I knew that he was going to shoot. When he started shooting, I fell on my side and pretended to be dead.”

One of his brothers also survived.

The man said that at one point, he was able to catch sight of his captors.

When we showed him several Wagner fighters who were photographed in Qasr bin Ghashir at the time, he recognised one as being among the men who abducted and shot at him and his family. We have identified him as Vladimir Andanov. An undated photo of him walking around Qasr bin Ghashir was posted online by GNA soldiers just hours after the killing.

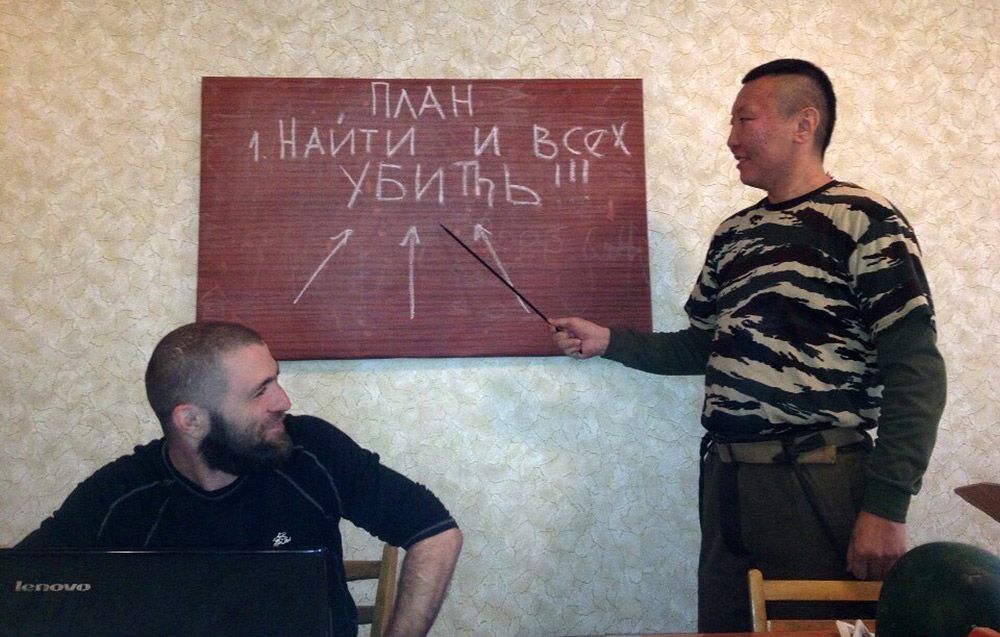

Social media account of ‘Vakha Donbass’

The board reads: 2016 – ‘The plan. 1. Find and kill everyone’

Ukrainian activists have identified his most recent location as North Africa. But some of those claiming to be his friends have denied on social media that he went to Libya with Wagner. They say he’s at home in Russia.

The BBC has also collected testimony of other civilian killings attributed to the Wagner group in Libya. It relates to those who have strayed into an active front line. The evidence suggests about a dozen civilians may have been killed by Wagner fighters during the Tripoli offensive. The casualties reportedly included three men and two women in civilian cars, who came under sniper fire.

A GNA fighter, Mohammed al Kahasy, also told us that four men fighting alongside him have been missing since they were intercepted in December 2019.

In addition to the red location dots on the tablet’s maps, black dots indicate another deadly legacy of Wagner’s presence in Libya – mines.

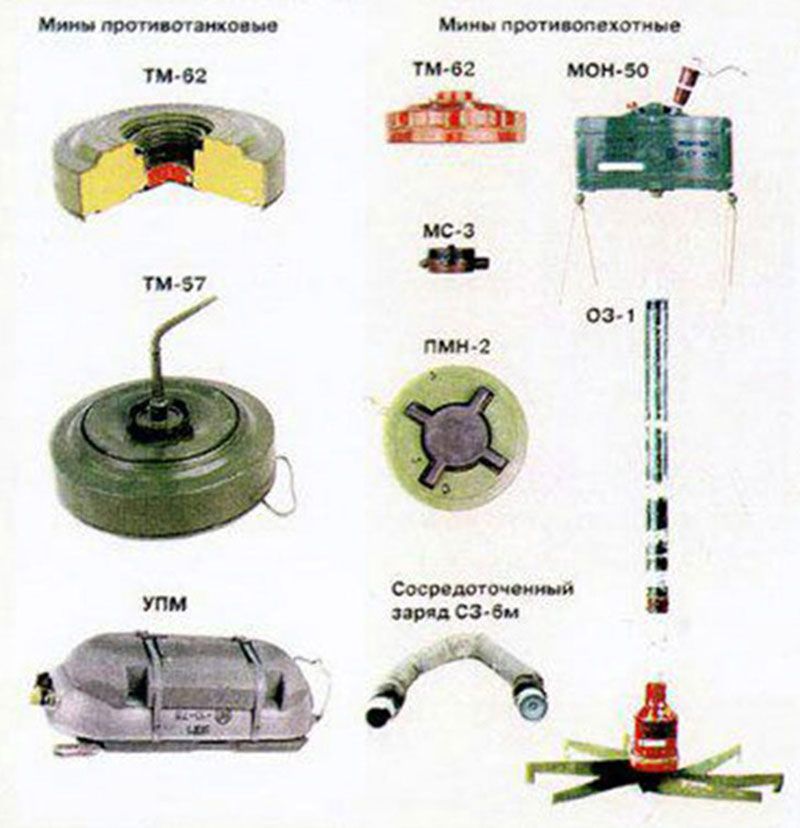

Many of the labels refer to specific types of mine – such as MON-50 or OZM. There are also positions marked as “mined district”, “remote controlled mine” or “stretched out” – which we understand to be slang for booby trap.

Like the red dots, some of the black dots are also labelled with the codenames of fighters, suggesting they may have been in control of those particular mine positions. The word Metla – Fedor Metelkin’s codename – appears again in this context.

All of the 35 mine positions marked on the tablet are in the residential district of Ain Zara.

Also stored on the tablet are illustrations of the MON-50 mine – and two other devices of Russian and Soviet origin, the POM-2 and the PMN-2. These weapons are all highlighted in a Human Rights Watch report which points out that none of them have previously been seen in Libya – where there has been an arms embargo for the past decade.

On the tablet was a diagram of different mines – including the MON-50 (top right)

A diagram of a POM-2 mine was found on the tablet

The BBC has heard testimony from local residents about the extent of mines and booby traps hidden in residential areas, and seen photos and videos of the devices.

We have contacted a de-mining charity working in Libya to alert them to Wagner mine positions which might not yet be officially documented.

The letters DU also appear on the Libya documents

When contacted for comment, Russia’s foreign ministry directed us to previous statements.

It said information about the presence of Wagner employees in Libya is mostly based on rigged data and is aimed at discrediting Russia’s policy in Libya. “Russia is doing its utmost to promote a ceasefire and a political settlement of the crisis in Libya.”

Wagner first emerged in eastern Ukraine in 2014, springing up alongside private military companies and volunteer brigades, backing pro-Russian separatists.

But it was in Syria in 2016, with its operations against the Islamic State group, that it became more prominent.

As for Wagner’s presence in Libya, the tablet with the cracked screen has shed new light on the group’s covert operations there – from troop movements to booby-trapping civilian neighbourhoods. Its owner and his comrades may be long gone from the locations marked on the on-screen maps, but the BBC understands from civilian testimony and open-source evidence that – despite a ceasefire – fighters are still in the country and continue to destabilise peace efforts.

Credits

Authors:

Nader Ibrahim – @nader_sm

Ilya Barabanov – @barabanch

Additional photos: Getty, Alamy

Published: 11 August 2021