“The Battle of High Hill”, The Atlantic Magazine

By Jeffrey E. Stern, photographs by Ian Allen for The Atlantic, October 2021 Edition

When two megafires converged on a small town in Oregon, the community faced a choice. People could flee, leaving the town to its fate. Or they could stay and fight.

At 6:58 p.m., a network of ground-based triangulation sensors began registering electrical pulses near a watercourse known as Beachie Creek. An electrical storm was passing through. There would be nine lightning flashes in a 42-minute period. The surge of current when lightning strikes a tree instantly turns moisture and sap to gas. Trees can shatter. Fires can start. Pinpointing specific origins can be difficult, but the storm on July 27 is a likely cause of what came to be known as the Beachie Creek Fire. Whatever the explanation, the fire did not immediately make itself known.

In real time—for almost three weeks—no one was aware of it. The United States was in the midst of the most active wildfire season ever recorded, fueled by high temperatures and widespread drought. Global climatic conditions were unprecedented. More than 3 million acres would soon be burning across California. More than 1 million would be burning throughout the Pacific Northwest. All told, wildfires would claim 10 million acres in the U.S. in 2020, more than double the acreage of the previous year.

[Your guide to life on a warming planet. Discover Atlantic Planet, a new section devoted to climate change and the ways it will reshape our world. Explore.]

Many small fires never amount to much. Others hide, nesting underground in root systems and feeding on “duff,” a layer of underbrush and leaves that have decayed and dried into slow-release fuel.

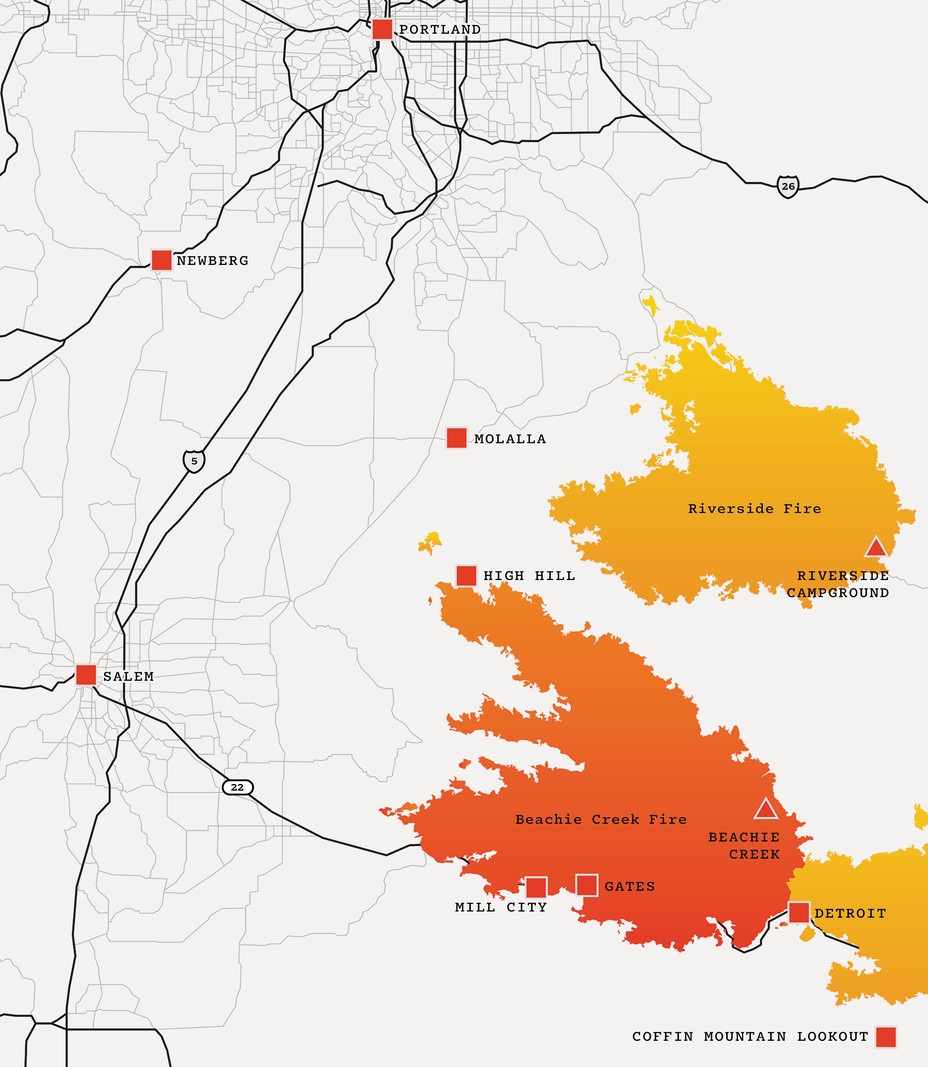

The Beachie Creek Fire was hiding. When it emerged, it became one of the biggest wildfires in the country—and was soon joined by another wildfire almost as big. The two megafires, angling toward each other, achieved maximum threat at a moment when most available firefighting resources were dispatched elsewhere. Left to oppose them were the citizens whose homes and towns stood in the fires’ path.

At 11:30 a.m., a seasonal firefighter at a hilltop lookout station spotted the first small sign that something was wrong: a thin coil of smoke rising above Beachie Creek. The smoke looked delicate—like fine strands of cotton caught in the treetops. The firefighter called the U.S. Forest Service’s dispatch center in Springfield, Oregon. “Smoke report,” he said. “Looks like it’s in the wilderness area,” meaning Opal Creek Wilderness, within the national forest. That was a problem. “Wilderness area” meant that, under the provisions of the Wilderness Act of 1964, road access was limited. No clearing had been done. The Opal Creek Wilderness was thick with old-growth trees that had been left alone. Some had fallen. Others, still standing, were rotted or dead. The area was layered densely with underbrush. Beachie Creek was especially hard to reach.

A week after it was detected, the Beachie Creek smolder covered no more than 20 acres. Even so, officials at the Willamette National Forest worried that it had the potential to spread. They requested help, but little was forthcoming. The forest where the fire had ignited was too thick for “initial attack” firefighters to penetrate. A team of smoke jumpers mobilized in Redmond, Oregon, to parachute in, but a reconnaissance flight found no place for them to land: The canopy was too heavy, the ridge too steep. Next, a team of rappellers was called in. They planned to slide down lines dangling from helicopters into the wilderness area. This time the concern was as much getting out as getting in: No place nearby could be cleared for an emergency landing zone.

A team of hotshots arrived—the most experienced and fearless wildland firefighters. Team members each carrying 40 pounds of gear hiked to Beachie Creek from the nearest road. They spent two full days bushwhacking up and down ridges until they found the fire on the knife-edge of a hill. Fighting fire on an upward grade is something to avoid. Flaming treetops tend to break off and come screaming downhill. Fire kills plants, and dead plants loosen their grip on the soil, sending boulders rolling. The hotshots declined the assignment. For a time, helicopters did bucket duty, dropping water to cool things off. But by late August, firefighters all over the West were overwhelmed. A 20-acre smolder deep in the wilderness was not a top priority. Requests for special assistance came back with the response “Unable to fill.” The helicopters were diverted to emergencies elsewhere.

Temperatures in western Oregon were rising at a time of year when they should have been starting to fall. The mountain snowpack, usually still melting in late summer—and feeding moisture into the forest—was already gone.

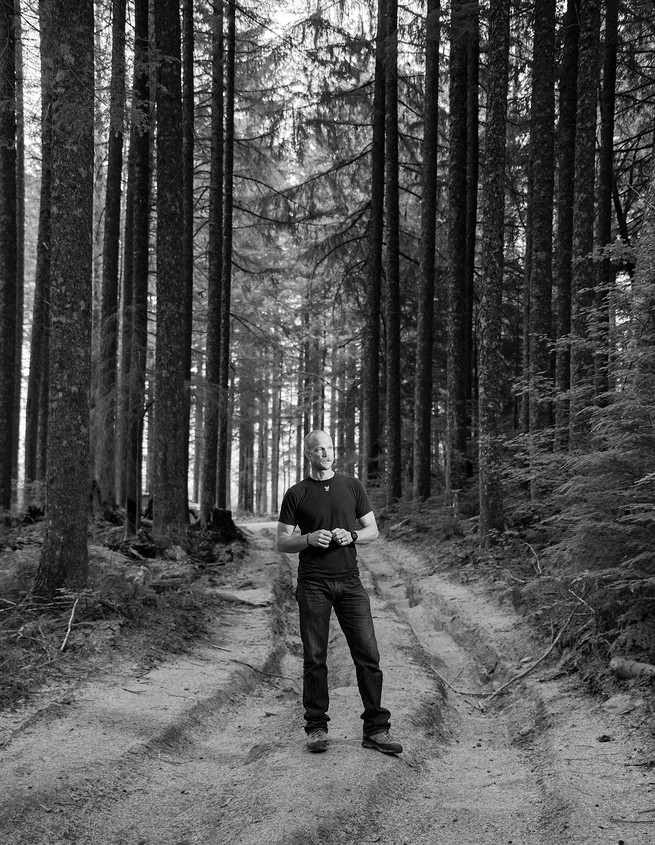

Ninety miles northwest of Beachie Creek, Dan Liechty watched a drone buzzing high above an excavation site. The company Liechty worked for, D+T Excavation, was grading a lot for a 244-unit subdivision in Willamette Valley wine country.

The drone was gathering topographical data to help workers move earth more efficiently. The brute excavation was done by bulldozers, backhoes, and retrofitted military-surplus trucks from the M809 and M939 series: massive six-wheel-drive vehicles, known as “five-tons,” that could traverse terrain at absurd angles on tires four feet in diameter. They carried water tanks and an assortment of hoses for mixing cement or moistening the soil so that it could be managed and shaped.

The company had more and more use for the five-tons, Liechty had noticed. In recent years, the soil seemed to be getting dry faster and earlier. The forests were, too. Liechty lived in a timber town called Molalla and spent much of his free time hunting and camping with his wife, Amanda, and their three children. He could sense the change. The smell of hemlock and fir was different—stronger, almost chemical. The snap of fallen branches underfoot was sharper. The air was so dry, it sometimes felt dusty.

Still, Liechty thought of his home environment more as rain forest than as fuel—the same lush ecosystem that had greeted pioneers on the Oregon Trail back in the 1840s. After struggling across the Cascades, most kept going farther west, toward the coast. But some laid eyes on the forests in the foothills and saw all they wanted. Molalla was named for the Native Americans the town largely displaced. Hemmed in by higher ground, it grew over the years, but not by much. The population only recently surpassed 9,500. Timber was king. People worked as tree fallers, or they drove logging trucks, or they turned fir into board at the mills.

But Molalla had begun to change. Conservation efforts had taken many forest tracts out of production. Several mills had shut down. Into the town came a trickle of people—blue-collar workers and coders and sportswear executives—who commuted every day to Portland, 40 miles north.

As he watched the drone, Liechty was anticipating the Labor Day weekend ahead. He was not thinking about a fire in the wilderness. Beachie Creek was some distance away, on the far side of the slopes. Wildfires didn’t happen in climates like Molalla’s, in the wet, western shadow of the Cascades. Besides, the rainy season would soon blow in from the Pacific.

Hundreds of miles above the North Pole, a weather satellite picked up an anomaly: a mass of Arctic air that was no longer above the Arctic. In the previous weeks, a series of tropical depressions had formed in the western Pacific and grown into typhoons—three in the span of two weeks. They had struck the Philippines, Japan, and Korea, and after hitting the Asian landmass they had spun north toward the pole, knocking the jet stream out of sync and unsticking a disk of cold air that usually sits over the Arctic. It was now on the move, sliding down across Canada, where snow was falling in strange places.

A dish array picked up the satellite reading and relayed it to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration supercomputer. The computer combined the satellite’s data with information coming in from thousands of other sources—balloons, ships, commercial aircraft, hobbyists tinkering in garages—and generated a weather model. This made its way to NOAA field offices all over the country, including one in Medford, Oregon, where a meteorologist named Brian Nieuwenhuis had just arrived at work for a weekend shift. At 3 p.m. he sat down in front of his five-monitor computer array, saw the latest weather model, and said out loud, “Oh no.”

Nieuwenhuis was looking at a once-in-a-career extreme weather event. The model showed a cold-air system that would soon be due east of him. Cold air meant dense air: particles packed together. Dense air meant high pressure. And high pressure meant wind, as air rushed to low-pressure areas. But the problem wasn’t just the abnormally high pressure to the east. It was also the abnormally low pressure to the west. Months of drought and record-breaking temperatures had cooked the air along the Pacific Coast.

Meteorologists who knew the Pacific Northwest expected September to bring gentle wind off the Pacific. The region was about to get the exact opposite. The winds would not be gentle—they would be hurricane-force. They would also be very dry. And they would not be blowing off the coast. They would be blowing toward the coast.

Nieuwenhuis issued a “critical fire weather” alert—the highest alert possible—for all of western Oregon. He then started working his way down a call sheet. He called state foresters, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management. He called coordination centers that distributed firefighting equipment across the state. Most wildland firefighters in the Northwest—and across America—were fighting fires already. Stretched-thin agencies had canceled time off. On one conference call, a fire manager in Rogue Valley, in southwest Oregon, cut to the chase. If there’s significant fire activity, he said, “no one is going to be able to come and help you.”

Other fire managers had trouble registering the scale of the threat. After one briefing by Nieuwenhuis, a wildfire dispatch officer asked, “Where do you expect those winds to be?”

Nieuwenhuis replied, “Everywhere. They’re going to be everywhere.”

As the Labor Day weekend came to an end, an unfamiliar breeze picked up in northwest Oregon. It seemed to be coming from an entirely different climate. In the Cascades, gusts began curling over mountaintops and running downhill to the west, gaining speed and losing moisture as they squeezed through ravines and accelerated through canyons. Trees were soon bending under winds that rose to 50 miles per hour, then gusted to 75 or more. In late afternoon, hot, dry, hurricane-force winds hit a patch of superheated forest floor near Beachie Creek. The smoldering fire detonated. It flattened and began to run. It threw up so much smoke from old-growth trees holding centuries of pitch that the fire itself disappeared under a smoke screen.

At the Coffin Mountain Lookout, a Forest Service employee was acting as a “human repeater,” transmitting radio messages between teams on either side of a ridgeline. She knew that the Beachie Creek Fire was on the move—it now covered some 500 acres. But even though the fire was in front of her, she couldn’t see the flames. All she could see was a thickening wall of smoke.

She was of no use up at the lookout. She hiked down to her Forest Service vehicle and drove to a ranger station in the town of Detroit as windblown branches clattered across the road.

At his home in Molalla, Dan Liechty was spending the end of the weekend with his 7-year-old son, the two of them tinkering with Liechty’s 1976 Ford pickup. Liechty noticed the wind—from the east, oddly. Spots started to appear on his clothing. They looked like snowflakes. His son made a face. It took Liechty a moment to recognize the spots as fallen ash.

Drawn from various agencies, a government team had been set up to coordinate the response to the Beachie Creek Fire. Brian Gales, from the Fish and Wildlife Service, was the incident commander. The fire was still relatively small, and deep in the wilderness. Gales and the interagency team had found a place to set up headquarters in the town of Gates, along Highway 22, an east-west road through the Cascades. The site was a Christian camp called Upward Bound. The staff had moved in, tacked up their maps, and plugged in their computers and printers. The command post was 10 miles from the fire.

And then, suddenly, it wasn’t. The wind became intense, knocking down trees and power lines all around the command post. Small blazes started everywhere. On the perimeter of the campus, the wind drove heavy debris into a chain-link fence. Wires sparked off the metal, and the debris caught fire. Members of the team put on their Nomex yellows, grabbed chain saws, and ran outside. They saw almost immediately that the task was hopeless.

Gales gave the order to evacuate. Staff members ran for their cars. Most had to abandon their equipment. The team fled west on Highway 22, intending to regroup in Mill City, three miles ahead of the fire. Before they could assemble, flames bore down on Mill City. The team fled farther west, to Stayton and then to Keizer. The fire followed, then slipped down into Little North Santiam Canyon, where residents who had gone to bed thinking danger was many miles away awoke to thumps on the roof. The fire was lobbing tree branches like mortar rounds. Embers lit the ground. The sky glowed orange. The fire was growing by nearly three acres a second, sucking oxygen out of the canyon.

Falling trees and whirling branches blocked escape by car. Those trying to run found the asphalt so hot that it burned through their shoes. Some people were overcome by lack of oxygen. The fire would soon claim its first lives. The state forestry office in Santiam Canyon was overtaken and destroyed. Up-to-date information was scant. The firefighters and Forest Service workers evacuating Detroit initially fled toward the fire rather than away from it.

The very nature of wind-driven fires added to the confusion. Although a satellite view might look almost orderly—Beachie Creek’s progress was clearly aligned with the wind—to those on the ground, wind-driven fires can foil any sense of direction. Flames seem to move every which way. Trapped gases blasting through pores in the wood generate explosive noise. The wind itself is loud. People standing face-to-face have to scream to be heard.

The fire continued its surge northwest, traveling so fast that local sheriffs skipped two levels of warning and jumped right to Level 3: “GO NOW.”

The Beachie Creek Fire spread to 100,000 acres in a matter of hours. And now a second catastrophe was developing.

At the Riverside Campground in Mount Hood National Forest, east of Molalla, sparks ignited the underbrush. No lightning strike had been recorded. The likely source was a human one—a fire left unextinguished by Labor Day campers. The Riverside Fire was out of control almost immediately. Driven by wind, it became a “running fire” with a well-defined leading edge and astonishing speed. Within minutes it was expanding west through the Clackamas River basin.

As the fire moved toward population centers, local fire departments deployed municipal crews to protect homes and businesses in their towns from spot fires. But few firefighters were available to fight the larger wildland fire. The Riverside Fire covered 40,000 acres within hours of ignition. It traveled nearly 20 miles in a single day. And it was heading for Molalla.

Meanwhile, to the south, the Beachie Creek Fire had by dawn grown to 130,000 acres. It, too, was heading for Molalla, pushing north into the foothills that marked a boundary zone between the town and the burning wilderness.

Matt Meyers was having a chaotic night when his cellphone buzzed. Normally he worked as a substation foreman for Portland General Electric, but the windstorm was wreaking havoc in Oregon’s largest city. Trees were down, power lines were down, and tens of thousands of people were without electricity. All of this was happening amid the months-long demonstrations in the city after the killing of George Floyd, in Minneapolis. Some clashes between protesters and counterprotesters, and between protesters and police, had turned violent. Federal officers had been deployed, over the objections of Oregon’s governor and Portland’s mayor. And then came the wind.

Portland General Electric had a storm center with a “wire down” desk, which forwarded reports to the field. Meyers led a team that took those calls. He was well suited to the work, with his orderly mind and instinct for organization. On the job, he had developed the habit of jotting detailed notes to keep track of his crew. There were a dozen ways to get hurt in an electrical substation, not to mention out in a windstorm with power lines coming down. He logged the problems and logged the personnel, and matched one to the other. He always knew where his people were.

Now, suddenly, in the early-morning hours, he had to leave. His wife, Lacey, had called from their home on the outskirts of Molalla.

“There’s a wildfire burning down the canyon from our house,” she said.

That couldn’t be right.

“You need to come home. They’re evacuating the neighbors.”

That couldn’t be right either. Fire near Molalla? Meyers had spent his whole life in the forest around the town. You didn’t get wildfires in Molalla. Eight months of the year, you couldn’t walk through the forest without coming away drenched. There was so much moss that the trees near his home seemed coated with tennis-ball fuzz.

Meyers made the 40-minute drive south, into the intensifying wind. He passed through Molalla’s town center and continued up into the foothills, toward his home. Coming over a rise, he saw his property, and the threatening glow just beyond. How could there be fire here? Why was there no official guidance? Why had the only alert come from his wife?

He did not know that the incident-command team monitoring the fire was on the run. He did not know that the northwestern United States had virtually exhausted its firefighting capacity.

Before sunrise, Dan Liechty drove from Molalla to the D+T Excavation site in Newberg. He intended to spend the day on the job. Earlier, Liechty’s wife, Amanda, had shaken him awake after receiving a text alert: “The mill’s on fire.” The mill was RSG Forest Products, a few miles away. Timber waiting to be milled was also burning—a massive pile, 30 logs high and a few hundred yards long. Smaller blazes flared around town, though the full force of the Beachie Creek and Riverside Fires remained some distance away. It did not occur to Liechty that his home was in danger. The mill fire was impressive, but an outlier. The spot fires seemed easy enough to control.

Liechty clocked in at work but couldn’t get anything done—he was getting too many calls and text messages from friends back home tracking the fires in the area. Liechty left work before lunch. By mid-afternoon, the narrow road home would be swollen with traffic escaping the other way: tourists in RVs, locals with livestock. A woman who made artisanal cheese drove a Subaru full of goats, packed butt to snout. Some vehicles held prisoners: Local penitentiaries were evacuating inmates.

When Liechty got home, the calls and messages continued. Some people needed an extra truck to move livestock or valuables; others needed help putting out small fires that threatened their homes or their timber. Liechty went to them.

Amanda called. “Where are you?” she asked. “We need to go.” Above the house, the sky had turned a wounded red. Amanda loaded the kids and the dogs into the SUV. Liechty went home to pack up items from the house. What to take: Food? Photo albums? Guns? He piled everything he could think of into his truck and met Amanda down at the elementary school, where evacuated families had begun to gather. Farmers brought animals to the parking lot, then went back to rescue more. An untethered horse galloped madly across the pavement.

Liechty checked his phone. Brock Ellis, a friend from a prominent Molalla family, was trying to reach him. The Ellis clan sold ranching and forestry equipment, and owned property all through the foothills. Brock explained that a fire was approaching the edge of his property. Liechty got into his truck and drove back up the road.

At his own home, also in the foothills, Matt Meyers, the power-company foreman, was packing a truck. Burning leaves fell to the ground around him. He felt helpless. Meyers called 911 and gave his location. The dispatcher said, “You absolutely need to get out of there.” Meyers sent his family to safety but stayed behind a little longer. If he was going to lose his home, he would at least bear witness.

He would later remember images of the area around his home. A forest tract that had been logged—now a prairie of stumps—had been flash incinerated. Heat from the fire had polished the stumps into onyx statuary. But Meyers’s house survived the night. In the morning, his phone rang. A voice said, “Meyers, this thing’s out of control.” It was Ben Terry, a friend from Molalla who now lived in Missoula, Montana, a nine-hour drive away. He and Meyers had been out of touch. But Terry still had family in Molalla. He also had a small flatbed truck with a 500-gallon water tank. And he had just bought some heavy-duty hoses. Terry said, “I’m loaded up. I’m headed your way. We’re going to fight this thing.”

As the Beachie Creek and Riverside Fires continued to grow, Oregon Governor Kate Brown held a press conference. “Let me start by bracing all of you for some very difficult news,” she said. “We are currently facing a statewide fire emergency. Over the last 24 hours, Oregon has experienced unprecedented fire, with significant damage and devastating consequences across the entire state. I want to be up-front in saying that we expect to see a great deal of loss, both in structures and in human lives. This could be the greatest loss of human lives and property due to wildfire in our state’s history.” Then, later, more bad news: “We are not getting any relief from weather conditions. Winds continue to feed these fires and push them into our towns and cities.”

Just out of view of the town, the Beachie Creek Fire had now surpassed 180,000 acres. It was at zero percent containment. The fire seemed to be pausing, as if to gather strength, on the far side of the foothills from Molalla, its leading edge sending fingers toward a summit outside town known as High Hill. The Riverside Fire, also just out of view, now covered 120,000 acres. It was also at zero percent containment.

High Hill became a natural point of convergence for Meyers, Liechty, and an initial group of about 20 other volunteers. They became aware of one another gradually and began to self-organize. To the south, the Beachie Creek Fire had already devastated five towns. Above them, smoke blotted out the sun. All around: ridges that fires could climb, government land laden with uncleared fuel, and timber-company tracts at the exact wrong moment in a 40-year rotation, densely packed with skinny trees not quite ready for “pre-commercial thinning.” As Meyers saw it, all that stood between the two fires in front of him and the town behind him were, in effect, hundreds of thousands of vertical matches.

Trained wildland firefighters were still busy elsewhere. Helicopters and air tankers were grounded because of the smoke. In the course of the day, the number of volunteers on High Hill fighting the Beachie Creek Fire would rise from about 20 to about 30 and then keep growing as word began to spread through town about neighbors trying to hold a line in the forest. Groups of volunteers mustered in other towns as well, directing their efforts at the Riverside Fire or at different fronts of Beachie Creek. It wasn’t just Molalla that the volunteers were protecting. Only a few miles to the northwest lay Canby (population 18,000) and Wilsonville (population 25,000); only a few miles due north lay Oregon City (population 37,000).

The volunteers had hand shovels, chain saws, and utility vehicles. Bulldozers and excavators began showing up from area companies. But the only water they had was from the 500-gallon tank on Ben Terry’s truck, and that wasn’t going to be anywhere near enough.

Tom Sleight, a diesel mechanic and fourth-generation farmer, solved the water problem with a Facebook message.

During the days of fire, the morning sounds from Sleight’s property became those of a small factory: engines being repaired, pumps being tested, rusted machinery being scraped back to life. Sleight was an apostle of self-reliance, a large, lumbering man with nimble fingers and a gift for tinkering. He was frustrated with the government—not an unnatural sentiment in Molalla. Criticism of forest management was widespread. Sleight’s interaction with federal officials consisted of little more than watching them show up to fence off parts of the forest, then disappear, leaving the fuel load to itself.

The acres around Sleight’s home resembled a steampunk sculpture garden. Some of the machines were semi-operational; some were losing a battle against nature. Sleight had a weakness for good deals on things he had no immediate use for: tractors, a bulldozer, tanker trailers, and a U-Haul long past its return-by date, a gift from a friend. Neighbors saw junk. Sleight saw independence.

As the Beachie Creek and Riverside Fires roared toward town, Sleight’s brother, Jon, had joined the volunteers. He saw firsthand that, without water, they stood no chance. Jon called his brother. He said, “Those tankers you’ve got—can you get them on the road?”

Yes, he could. He could get two tankers he’d bought off an old employer, Willamette Egg, on the road right away. The 6,000- and 3,000-gallon vehicles had been used to transport liquid egg but could handle water just as easily. Sleight had a few other prospects out in his yard, but he couldn’t reanimate them by himself. He got on Facebook and sent out a call for help. Then he climbed into the larger of the egg tankers, headed into town, broke into a fire hydrant, and drew water from the Molalla water main.

Sleight drove 10 miles south, into the hills, and found a staging area, a patch of gravel near Hansen’s Christmas-tree farm. The second tanker would come later. A plan was forming. The tankers would serve as mother ships, feeding smaller vehicles that could take water right to the fire. Now Sleight just needed the smaller vehicles.

He left the tanker behind and rode with his brother back down the hill. Nearing his property, he saw that three service trucks and seven or eight pickups were gathered, idling. As he drew closer, he began to recognize the people inside. They were friends with skills: welders, machinists, fabricators. The Facebook message had worked.

He went to his safe, took out $12,000, and began handing it out. “Anyone who can,” he said, “run down to Harbor Freight and buy pumps and hoses and valves.” A friend from a farm nearby had dropped off at least a dozen large totes—pallet-size, 275-gallon bladders used for various purposes on farms. Sleight installed a bladder or two in the back of each pickup, hooked the bladders up to pumps and hoses, and sent the fleet of makeshift fire trucks to the Christmas-tree farm. The trucks filled up at the tankers and then made for the fire.

A continuous supply of water was going to take more than two tankers. Sleight made some calls. A local company, Molalla Sanitary, filled trucks with water and sent them up to the Christmas-tree farm. A friend of Sleight’s had a 40-year-old fire truck that had been repurposed to pump liquid manure for his dairy. The pump wasn’t working, but the truck had a tank. Sleight had a friend climb inside and fix the pump.

On High Hill, Matt Meyers had slipped naturally into the foreman role. He jotted down names of arriving volunteers and always knew who was where. As Sleight’s makeshift fire trucks began to arrive, it was Meyers who knew where to send them.

A four-wheel ATV became his command post. He laid a map out on the seat. He had three radios. The smoke was so thick, the terrain so steep, and the forest in places so dense that he often couldn’t see more than a few meters in any direction. But as volunteers radioed in their positions, he began to get a sense of the fire’s shape. He could picture its leading edge, and he knew it had to be about three miles wide. He figured out which parts of the fire would be easiest to reach, thanks to old logging roads, and which parts would be hard or impossible to get to. His overall strategy was simple: Attack ground fire and flare-ups with water—a holding action—and put most of the muscle into digging fire lines. The idea was to block the entire three-mile front.

Most of the volunteers were familiar with the concept of fire lines: removing fuel in a fire’s path. Some, like Dan Liechty, had spent a summer fighting wildland fires. Removing fuel meant clearing roots, underbrush, branches, and duff. It often meant felling trees. It meant clearing a path some 10 feet wide and several miles long, and then clearing another behind it as insurance, and sometimes even a third contingency line behind that one.

The interagency response team was at last back in business, having set up at a community college in the state capital. Brian Gales, the incident commander, got his fire-behavior analyst and his meteorologist on an urgent conference call with law enforcement and state officials.

On the call, Gales asked the meteorologist for the forecast. Computer models suggested that the wind, though beginning to ease, would persist for several more days. The fire-behavior analyst weighed in. He had been studying models of the fuel and the topography. The landscape offered no natural holding features. No body of water or clearing. No break in the fuel supply.

The two fire systems were not just moving on an unobstructed path. They were also moving toward each other. They were going to merge. When they did, convection would accelerate. Air and vapor would shoot upward until they reached the colder temperatures high above, possibly condensing into pyrocumulonimbus “fire clouds.” The merged fire could create its own lightning. It could create tornadoes. It could expand in every direction at once.

The experts on the call agreed that evacuation levels across northwest Oregon had to be raised immediately. They sent out a relay of alarms. One local fire chief received word from a state official, who warned of a “plume-driven fire event.” Asked to put that another way, the state official said, “Apocalyptic fire behavior.”

In Clackamas County, firefighters heard the alarm over the radio: “Disengage all firefighting activities.” In Portland, whose southeastern suburbs were potentially threatened by the wildfires, Mayor Ted Wheeler declared a state of emergency. In Molalla, the municipal fire department was evacuated. The state forestry department was evacuated. Police cars rolled down Main Street, loudspeakers repeating a single message: “You need to evacuate the city. Evacuate now.”

Tom Sleight was calling again. As he worked to keep his water convoy up and running, he had found an ally in Ashley Bentley, asking her to find more pumps, hoses, and valves. Now he wanted a magnetic light to put atop his vehicle. Because of the smoke, up on the front lines, it was always dark.

Bentley had a powerful voice honed as a ministry singer, and a pragmatic and adaptable spirit. She and her husband, Brian, had taken the business his family had built for farm animals and turned it into one that could also meet the needs of suburbanites’ designer dogs. Just about everyone in Molalla had animals, whether livestock or pets. As the fire drew closer, the century-old Bentley Feed Store became a nerve center.

Bentley learned that none of the volunteers had chain-saw chaps. A lot of them were working without hard hats. They were also going through boots fast, because the ground was so hot. She contacted a supplier called Coastal Farm & Ranch; with help from the people of nearby Albany, the supplier provided crucial protective gear. Bentley dispatched runners to other stores for supplies. She sent the volunteers energy drinks. Lotion for poison oak. Lip balm. Visine. Chewing tobacco.

Bentley used older people in town as delivery drivers. Some supplies came from far away. As time went on, donations seemed to arrive from everywhere. Once, several well-dressed women stepped out of a shiny black SUV. “From the LPGA,” one of the women said. The Cambia Portland Classic golf tournament had been cut short because of the fires. The women had hamburgers and boxed lunches to give away.

To keep track of what had to be delivered where, Bentley marked bins with the names of various battlefronts: Redhouse Road, Leabo Road, Ramsby Road, Maple Grove. She filled the bins with what the volunteers at each front needed.

The volunteers didn’t know about the merge threat. On High Hill, they were mostly out of cellphone range. But they were functioning like an experienced team: cutting down trees, digging out duff, and making their way onto federal, state, and private property. Matt Meyers couldn’t provide GPS devices, but he could speak in shorthand that drew on local lore. Meyers grabbed an old friend: “Remember where Brian Ferlan killed his first buck? I need you to take a crew and a truck over there.” He directed another team to “the second Port Blakely gate”—a timber-company tract—“right across from John and Barb’s.”

Meyers began to sense, from the changing map in his mind’s eye, that the team was making progress. Fingers of fire shot up everywhere, but the 30 volunteers had swelled to 60. The number would soon grow to more than 100. One early volunteer had shown up on a small bulldozer, her border collie riding shotgun. Another, a wildland firefighter from Molalla deployed elsewhere in the state, left his post to join the volunteers in his hometown. Meyers had everyone spread out along the hills to positions ranging more than two miles on either side of him. They cleared a dozen miles of fire lines in zigzagging paths in front of the fire’s leading edge.

Tom Sleight’s makeshift fire trucks—the pickups with the farm bladders—were getting into smaller and smaller patches. That was good. But they couldn’t get into some of the most thickly forested areas or up and down the steepest grades. Those were the places where fighting fire was most dangerous, and thus places where fire was most likely to slip through. Volunteers with hoses and backpack sprayers did what they could.

Conditions were difficult. Meyers knew enough about wildfires to know that the greatest risks weren’t always the obvious ones. It wasn’t just entrapment—finding yourself suddenly overtaken by flames and having nowhere to go. There were gravity hazards to contend with: falling trees and branches, tumbling rocks. There was smoke inhalation, and the danger posed by extreme physical exertion under extraordinarily hot conditions. You have trouble staying hydrated. Your core body temperature rises. Your heart pumps faster. Wildland firefighters sometimes succumb to sudden cardiac events. Sustained physical exertion without rest can cause muscles to dump so much protein into the bloodstream that kidneys fail, and active young men and women end up on dialysis. One of the biggest dangers was simply riding in heavy vehicles off-road; getting to a fire can be as dangerous as fighting it.

Tom Sleight went gunning toward the front lines. He had just heard from his ex-wife, Dawn, who worked at a nearby state forestry office and said that the two fire systems were about to merge, right here, just outside Molalla. Sleight was desperate to warn the volunteers—he knew they’d likely have no idea. The first person Sleight ran into, a mile or so from the front line, was from the state forestry office, one of the few responders on the scene from any government office. Sleight asked if he’d heard that the fires were about to merge.

“That’s just Facebook crap,” the forester said.

“No, this is legit,” Sleight said. “This is from Dawn.” He persuaded the forester to go as far down the hill as he needed to find cellphone service and check with headquarters. The call changed the forester’s mind. Sleight set off to warn the volunteers. The forester set off to warn any official responders.

Eventually the two of them caught up with Meyers, who could reach almost everyone by radio. Meyers didn’t want to believe what he was hearing. He was convinced that the volunteers were finally beating this thing, that they had it under control. The state forester said, “You need to know that these fires right now are so big, and so hot, that there’s smoke they can see from satellite radar as far away as Hawaii. And then it circles up to the north and is dropping all the way into New York City.”

The ping of a voicemail message woke Meyers from a fitful sleep. He was at a friend’s house. He had barely slept in four nights. Still, he rose every half hour to see if flames had reached the town. He figured his home in the hills was gone by now.

Then came the voicemail message.

Dan Liechty, sleeping in a trailer, had received one too.

A few volunteers with homes near High Hill had stayed close to the fire. One of them had come down into cellphone range to report to the team. The fire lines they had dug were holding. The two fires had not yet merged. And it felt like the wind was doing something—changing, easing, just a little.

The Riverside Fire now covered 130,000 acres. Beachie Creek was approaching 190,000. This was not the moment to stop. It was time for one more push.

Before sunrise, up in the foothills, the volunteers gathered.

Meyers was back on his ATV, map spread out, the three radios connecting him to all parts of the operation. He sent local volunteers out to spray-paint numbers on remote roads and landmarks—guidance for those less familiar with the terrain. There were more such people, as the ranks of volunteers continued to grow. Meyers would get on a radio: “Drive up the road ’til you see the 2 and go down about a quarter mile. You’ll find Brian. He’s on a four-wheeler, and he’ll tell you what he needs.”

On a four-mile stretch of High Hill, the length of fire lines dug by the volunteers grew to 30 miles. The Beachie Creek Fire kept trying to creep over the ridge, angling toward the Riverside Fire. The volunteers fought back. Another crew, on Ramsby Road, to the northeast, worked to contain Riverside’s aggressive reach. As the hours went by, the volunteers on High Hill protected their flank by driving fire lines progressively to the east, holding Beachie Creek in check where the threat of a merge with Riverside was greatest.

But the defenses had a weakness. On the steepest sides of the hills, the extreme grade made digging fire lines impossible. The makeshift fire trucks could not get close enough to direct water at the flames. In one area, volunteers tried going in with bulldozers, but the sector was so hot that one of the machines caught fire. Those steep sides represented a serious vulnerability. If the fire could break through there, none of the other work would matter.

Liechty was working near the crest of High Hill, in a cleared area, when he happened into a trace of cell service and his phone rang. It was Tim Ellis, Brock’s father. He was wondering about the six-wheelers in Newberg—those five-ton military-surplus trucks retrofitted with water tanks, spray nozzles, and hoses. Would D+T Excavation give them up? In all the chaos, Liechty hadn’t given the five-tons a thought. Standing inside that tenuous circle of cellphone service, Liechty called his boss. D+T agreed immediately to send two trucks and two drivers.

Within a few hours, they were on the scene. The five-tons trundled to life. The water tanks were filled. For the first time in their post-military lives, the five-tons had a frontline mission. They could follow the fire lines, wetting down trees and underbrush on either side. They could also bushwhack and make their own trails. Their giant tires and six-wheel drive took the trucks over downed logs and boulders, through the most thickly forested part of the hills, and up near-vertical ridges. The drivers could get the five-tons right up to the leading edge of the fire and into some of the hottest spots. From inside each cab, a lever was shifted that took the truck out of gear and diverted engine power to a water pump. The driver stepped on the gas and flipped a row of switches on a console. Water sprayed from nozzles on the front, sides, and rear. From a nozzle on the roof, it came blasting out as if from a water cannon, reaching nearly 100 feet into the maw of the fire.

The fire lines held. And over the next week, outside help finally started to show up in significant numbers: hotshot crews, state foresters, and U.S. Forest Service personnel. Private firefighting crews began to arrive, sent by insurance companies—a benefit many homeowners hadn’t known they’d had. The crews cut burnable vegetation from around houses, sprayed fire retardant on walls and roofs, and filled gutters with water. Everyone relied on Tom Sleight’s tankers. By the next week, upwards of 1,000 people were fighting fire on the slopes, in Molalla and other towns. Teams and equipment arrived from beyond Oregon; 260 firefighters even arrived from Canada.

At least as important, nature itself began to cooperate. Wildland firefighters can’t “put out” a megafire. At best they can contain the fire until the weather changes or it runs out of fuel. That is what the volunteers had done. Now, at last, the winds were diminishing. Temperatures were dropping.

It would take another six weeks before the Beachie Creek Fire was declared fully contained. The Riverside Fire was not declared contained until December. The damage was without precedent. Over the previous five years, Oregon had lost 93 homes to wildfires. In the year 2020 alone, the state lost more than 4,000 homes, nearly all of them during those few days in September. Eleven people had perished. Many more would have died, and even more damage would have been done, if the Beachie Creek and Riverside Fires had merged. Miraculously, Matt Meyers’s house in the hills escaped the blaze. So did Tom Sleight’s junkyard. So did Dan Liechty’s house in Molalla, along with the entire town.

When the incident-management team working out of Chemeketa Community College looked back at the event, its members understood that disaster had been averted with help from a band of private citizens. Fire officials are vocal in discouraging amateur firefighting—it puts lives in danger. They want people to evacuate when told to do so. But the circumstances involved in the Beachie Creek and Riverside Fires had been exceptional. So had the response. Fire officials explained as much to Governor Brown when she toured the devastation in northwest Oregon.

The governor held another briefing about the state’s worst-ever wildfire season. She closed her remarks by highlighting the volunteers who had held fast on the high ground outside Molalla and elsewhere—“the real heroes of the Beachie Creek Fire.” The governor’s spokesperson later elaborated, citing the “many miles of containment lines” that were dug and hacked by volunteers “when all state and national firefighting resources were tapped out.”

Two days after that press conference, Matt Meyers woke up to a morning as dark and gray as every smoke-filled day for the past two weeks had been. When he stepped outside, he noticed that the ground was wet. A month overdue, the rains had finally come.

This article appears in the October 2021 print edition with the headline “The Battle of High Hill.”