Zhang’s frozen unconscious body had been found by a passing shepherd who’d wrapped him in a quilt and carried him over his shoulders to safety. He was one of the lucky ones.

In May this year, 21 competitors died at an ultra-running event in northern China hit by extreme weather conditions: hail, heavy rain and intense gales caused temperatures to plummet, and nobody seemed prepared for it.

Only a small number felt comfortable talking about what happened – and some have been threatened for doing so.

The sun was out on race day in Baiyin, a former mining area in China’s Gansu province. Some 172 athletes were ready to run 62 miles (100km) through the Yellow River Stone Forest national park.

The organisers were expecting good conditions – they’d had mild weather the previous three years. They had even arranged for some of the competitors’ cold-weather gear to be moved forward along the course so they could pick it up later in the day.

But soon after Zhang arrived at the start line, a cold wind began to blow. Some runners gathered in a nearby gift shop to take shelter, many of them shivering in their short-sleeved tops and shorts.

Zhang started the race well. He was among the quickest to reach the first checkpoint, making light work of the rugged mountain trails. Things started to go badly wrong just before the second checkpoint, some 20km into the course.

“I was halfway up the mountain when hail started to fall,” he later wrote in a post on Chinese social media. “My face was pummelled by ice and my vision was blurred, making it difficult to see the path clearly.”

Still, Zhang went on. He overtook Huang Guanjun, the men’s hearing-impaired marathon winner at China’s 2019 National Paralympic Games, who was struggling badly. He went across to another runner, Wu Panrong, with whom he’d been keeping pace since the start.

Wu was shaking and his voice was trembling as he spoke. Zhang put his arm around him and the pair continued together, but quickly the wind became so strong, and the ground so slippery, that they were forced to separate.

As Zhang continued to ascend, he was overpowered by the wind, with gusts reaching up to 55mph. He’d forced himself up from the ground many times, but now because of the freezing cold he began to lose control of his limbs. The temperature felt like -5C. This time when he fell down he couldn’t get back up.

Thinking fast, Zhang covered himself with an insulation blanket. He took out his GPS tracker, pressed the SOS button, and passed out.

Closer to the back of the field, another runner, who goes by the alias Liuluo Nanfang, was hit by the frozen rain. It felt like bullets against his face.

As he progressed he saw somebody walking towards him, coming down from the top of the mountain. The runner said it was too cold, that he couldn’t stand it and was retiring.

But Nanfang, like Zhang, decided to keep going. The higher he climbed, the stronger the wind and the colder he felt. He saw a few more competitors coming down on his way up the mountain. His whole body was soaking wet, including his shoes and socks.

When he finally did realise he had to stop, he found a relatively sheltered spot and tried to get warm. He took out his insulation blanket, wrapping it around his body. It was instantly blown away by the wind as he’d lost almost all sensation and control in his fingers. He put one in his mouth, holding it for a long time, but it didn’t help.

As Nanfang now started to head back down the mountain, his vision was blurred and he was shaking. He felt very confused but knew he had to persist.

Halfway down he met a member of the rescue team that had been dispatched after the weather turned. He was directed to a wooden hut. Inside, there were at least 10 others who had decided to withdraw before him. About an hour later that number had reached around 50. Some spoke of seeing competitors collapsed by the side of the road, frothing at their mouths.

“When they said this, their eyes were red,” Nanfang later wrote on social media.

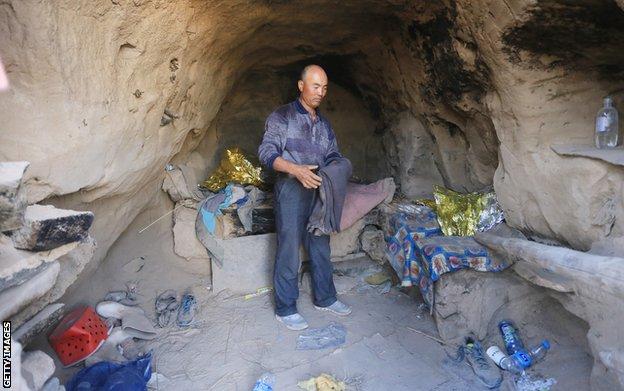

Zhang, meanwhile, had been rescued by the shepherd, who’d taken off his wet clothes and wrapped him in a quilt. Inside the cave, he wasn’t alone.

When he came to, about an hour later, there were other runners also taking refuge there, some of whom had also been saved by the shepherd. The group had been waiting for him to wake up so they could descend the mountain together.

At the bottom, medics and armed police were waiting. More than 1,200 rescuers were deployed throughout the night, assisted by thermal-imaging drones and radar detectors, according to state media.

The following morning, authorities confirmed that 21 people died, including Huang, who Zhang overtook, and Wu, the runner he’d kept pace with at the start of the race.

A report later found that organisers failed to take action despite warnings of inclement weather in the run up to the event.

As news of the deaths broke on social media, many people questioned how the tragedy could have happened. Some competitors, such as Zhang and Nanfang, chose to write about their experiences online to help people understand what it was like.

But Zhang’s post, written under the name ‘Brother Tao is running’, disappeared shortly after it was published.

When Caixin – a Beijing-based news website – re-uploaded his testimony, a new post appeared on the account a week later, begging the media and social media users to leave him and his family alone.

It later transpired that Zhang had suspended his account after people questioned his story. Some accused him of showing off for being the sole survivor at the front of the pack, others had sent him death threats.

“We don’t want to be internet celebrities,” he wrote online, adding that the man who saved him had also faced pressure from the media and “other aspects”.

“Our lives need to be quiet,” he wrote. “Please everyone, especially friends in the media, do not disturb me and do not question me.”

The survivors weren’t the only ones to find themselves put under pressure.

One woman, who lost her father in the race, was targeted with social media abuse on Weibo after questioning how her father was “allowed to die”. She was accused of spreading rumours and using “foreign forces” to spread negative stories about China.

Another woman, Huang Yinzhen, whose brother died, was followed by local officials who she claimed were trying to keep relatives from speaking to each other.

“They just prevent us from contacting other family members or reporters, so they keep monitoring us,” she told the New York Times.

In China it’s typical for relatives of those who have died in similar circumstances – where authorities face blame – to have pressure placed on them to remain silent. For the government, social media attention on any possible failings is not welcome.

A month after the race, in June, 27 local officials were punished. The Communist Party secretary of Jingtai County, Li Zuobi, was found dead. He died after falling from the apartment in which he lived. Police ruled out homicide.

The Baiyin marathon is just one of many races in a country that was experiencing a running boom. Its tragic outcome has brought the future of these events into question.

According to the Chinese Athletics Association (CAA), China hosted 40 times more marathons in 2018 than in 2014. The CAA said there were 1,900 “running races” in the country in 2019.

Before Covid hit, many small towns and regions attempted to capitalise on this by hosting events in order to bring more tourism into the area and boost the local economy.

After what happened in Baiyin, the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection accused organisers of some of the country’s races of “focusing on economic benefits” while they are “unwilling to invest more in safety”.

With Beijing’s hosting of the 2022 Winter Olympics just months away, China has suspended extreme sports such as trail running, ultramarathons and wingsuit flying while it overhauls safety regulations. It is not yet clear when they will restart. There have been reports that not even a chess tournament managed to escape the new measures.

But without events like these, people wishing to get involved, perhaps even future star athletes, are finding themselves frustrated. In some cases, as Outside Magazine points out, athletes could take matters into their own hands, venturing into the mountains without any regulation whatsoever and putting themselves at risk.

Mark Dreyer, who runs the China Sports Insider website, wrote on Twitter: “If this incident has removed the top layer of the mass participation pyramid – as seems likely – there’s no telling what effect that would have at the lower levels.

“The long-term effects of this tragic – and avoidable – accident could also be significant.”