“Remembering The Arch: Can the example of his life help us restore our broken politics?”, Daily Maverick

By Mcebisi Jonas, Johannesburg, 30 Dec 2021

Archbishop Desmond Tutu died last week, perhaps the last great representative of a generation of giants. What lessons in leadership can we take from his life in a new and less stellar era in our politics? Because if we cannot understand and recover what we have lost, then we will struggle to find the way forward.

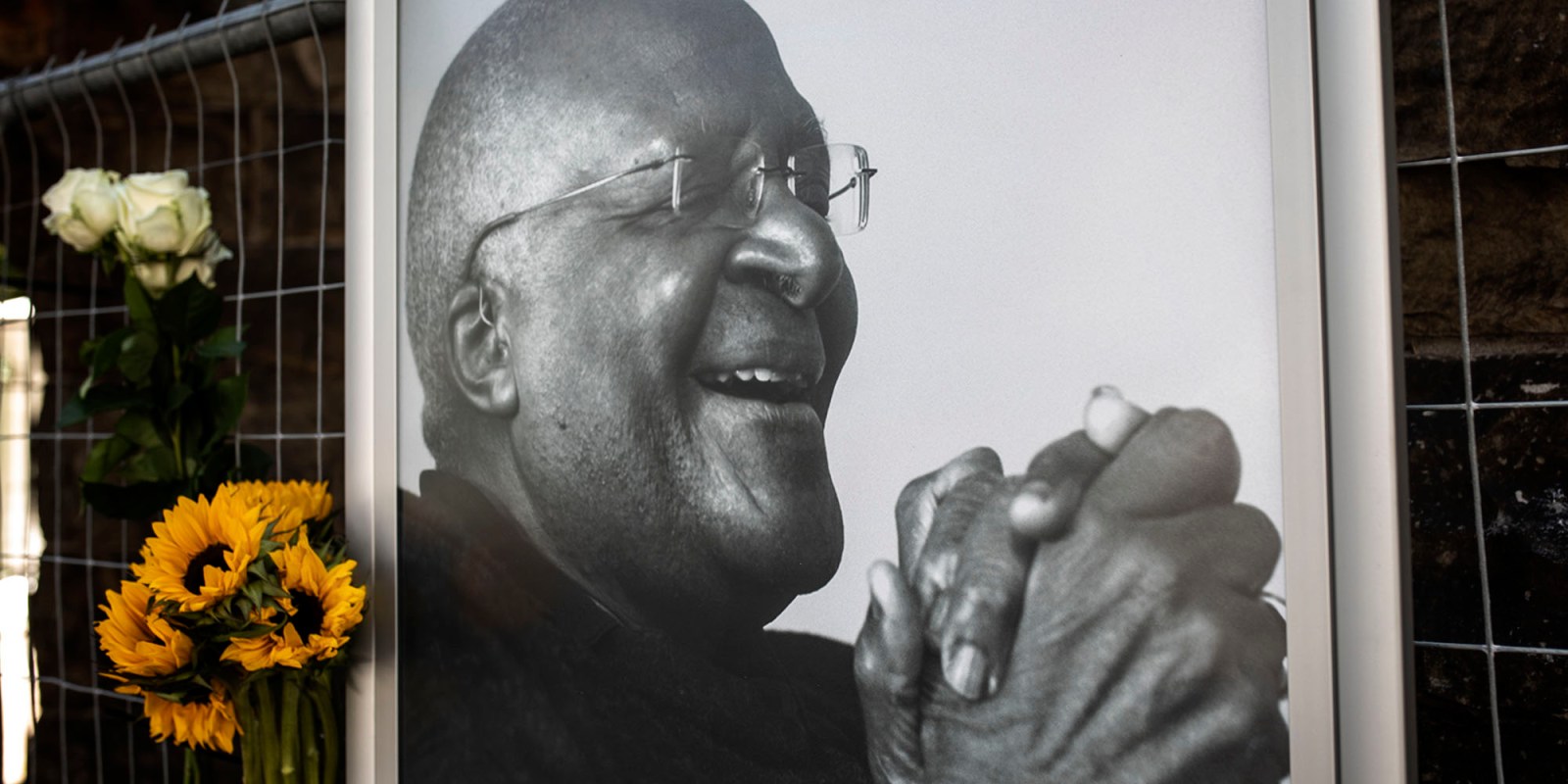

DESMOND MPILO TUTU (7 OCTOBER 1931 – 26 DECEMBER 2021)

Desmond Tutu, first and foremost, had a spine of steel. He had not just the moral courage to speak truth to power when he saw injustice or wrong – be it against the apartheid regime in South Africa, or the apartheid state in Israel – but extraordinary physical bravery. No one who witnessed it will ever forget how he threw his diminutive frame into the middle of angry mobs to prevent the lynching or necklacing of alleged informers at mass funerals.

He was a unifier, a trait in short supply in these times of political factionalism and rancour.

His entire life was built on selflessness and humility. While we do not expect our leaders to behave like monks, few would dispute that many of our problems result from a hunger by the new elite for power and material wealth at the expense of the common good.

The Arch had a sense of humour. The feminist author bell hooks, who died the week before Tutu, wrote that “we cannot have a meaningful revolution without humour”.

The jokes were not all that funny. Back in the eighties he had audiences in stitches when he spoke about a land where toilets were reserved for people like him with large noses and where, to attend the Large Nose University, one had to get permission from the Minister of Small Nose Affairs.

Through these stories he deployed a common language to communicate the pain, the hurt and the absurdity of apartheid and to open us up to a deeper humanity.

Tutu has been described in eulogies this week as South Africa’s moral compass. Nelson Mandela famously said he was the voice of the voiceless.

In this conventional understanding, he stands outside politics. Indeed, it was an iconic moment on 12 February 1990 when he joyfully stepped aside at Bishopscourt for the newly released Mandela and his comrades to take over the political project. His role, he emphasised, had merely been as a caretaker while others were locked up or banned.

Tutu’s standing in the democratic South Africa was framed by his extraordinary leadership at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. After that his relations with the Mbeki and Zuma presidencies grew increasingly tetchy and culminated, at least initially, in his being disinvited from Mandela’s funeral at Qunu in 2013.

The tension between church and state is an age-old phenomenon, one that is driven by the fact that men of the cloth have of necessity a different perspective than politicians. But in South Africa, the detachment of the “moral” universe from the political one has perhaps gone too far.

It would be wrong however to reduce Tutu to simply being a troublesome priest – shades of Archbishop St Thomas à Becket, who was murdered in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170.

It is important to remember that the work Tutu and other church leaders did in fighting oppression and mobilising the people was always political.

For too long we have tended to downplay or minimise their role in shaping the narrative of liberation as a struggle between good and evil and a march towards the promised land. Not for nothing is Nkosi Sikele i’Afrika our national anthem.

The theologian John de Gruchy wrote that, “Tutu journeyed into the suffering of people and tried to find meaning in the darkest of times”. Tutu tapped into the spiritual energy of a deeply religious people.

His faith sprang from a belief in the fundamental worth of ordinary people – in the great spirit of the oppressed and in the hope that even those who hate could be reached with reason and love. And in many ways, it was this vision that won our democracy.

The extent to which we have become unmoored from that vision can be seen in the angry young voices, not even born when the new South Africa was created, accusing Tutu this week of being a sell-out.

Much of it can be blamed on the vacuousness and ignorance of social media, accentuated by the growing depoliticisation of politics, and the weakening of parties and any philosophical ideas that they might represent.

At the same time, we have to acknowledge that part of the rage is founded upon profound frustration that instead of the promised land, so many of our people are mired in poverty, joblessness and despair.

Many believe that the very concept of reconciliation was a sop to white fears and therefore stunted the true transformative purpose of liberation. But does this discontent arise from the shortcomings of the vision that lay behind the compromise of 1994 or the failure of our politics in the years since, including the damage wrought by the State Capture years?

Of course, the TRC was not merely designed to forgive white people their sins. Its animating power was that it went to far-flung parts of the country and gave voice to many thousands of victims of the apartheid system and its security forces. It was about bearing witness; its extensive archive stands as a document of significance in the founding of our nation second only to our democratic constitution.

Tutu played an enormous role in the framing of our experiment in democracy. But the word ubuntu is overused these days and the rainbow nation, a term attributed to Tutu, has also fallen on hard times. We need to find a new unifying vocabulary for a different moment.

There is an element of a nation that is both spiritual and moral in nature – and this was especially the case in the founding of South Africa – and it is that which we are in danger of losing.

Tutu once said that, “Our world is in the grips of a transformation that continues forward and backward in ways that lead to despair at times but ultimately redemption.”

This sounds a lot like the words of another pastor, one whom he admired and revered, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr who said the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.

Our country – and indeed much of the world – is crying out for visionary leadership. We will not find it among the demagogues or populists.

If we are to manage a reset, we could use a little bit of Desmond Tutu’s bravery, his call to act, and stand on principle and his optimism that despite all the evidence, it is still in our power to make the world a better place.