“How Martin Luther King Jr. Changed His Mind About America”, Time Magazine

By Kermit Roosevelt III, January 17, 2022

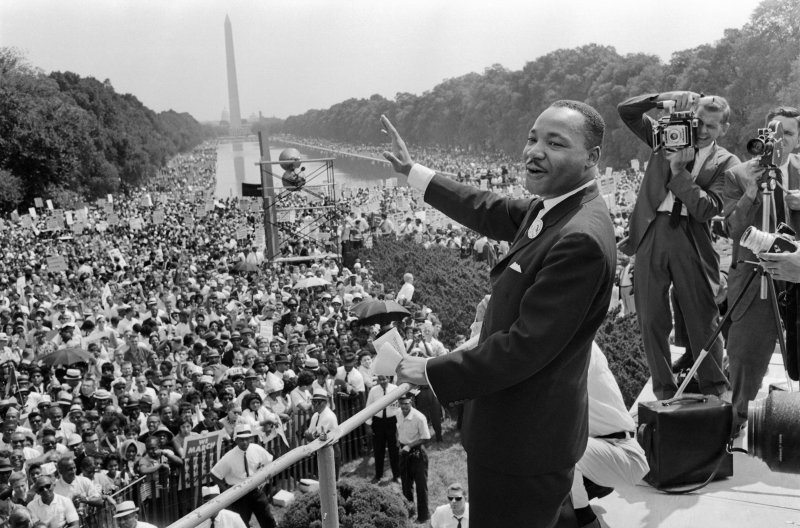

More than fifty years after his death, Martin Luther King Jr. remains a towering figure in the history of American civil rights. As with most influential thinkers, there is a certain amount of ambiguity in the public understanding of King and his legacy. White Americans were very skeptical of King while he was alive, but as his reputation and popularity grew, advocates of very different positions tried to claim him for their own. Nowadays conservatives are fond of invoking his most famous speech, 1963’s I Have a Dream, with its vision of a world in where people “will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Progressives are fonder of The Other America, a more radical speech from 1967, where he said that we may “have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words of the bad people and the violent actions of the bad people, but for the appalling silence and indifference of the good people who sit around and say ‘wait on time.’”

Those two Kings are ones we know, but there are other Kings we need to listen to as well. The I Have a Dream speech gives us the standard story of America. According to this story, America starts with the Declaration of Independence, which states our foundational values, particularly equality. The Founders’ Constitution turns these values into law—imperfectly at first, but American history is a progress towards redeeming the “promissory note” of the Declaration, and one day we will “live out the true meaning of … ‘all men are created equal.’”

This story is comforting and reassuring, but it is actually a barrier to progress, as the King of The Other America came to see. For one thing, it supports what he called the indifference of the good people, the idea that social progress “rolls in on the wheels of inevitability.” For another, it tells us to look to Founding America and the Declaration of Independence as the source of our fundamental ideals. But doing that tells us that those ideals can co-exist with white supremacy. The truth is that Founding America was not a nation dedicated to our idea of equality. The Betsy Ross flag shows us thirteen stars in a circle, and every star represents a state where slavery was legal.

The idea that the Declaration provides the way forward is deeply problematic. A younger King saw this. As a junior in high school in 1944, competing in a debate contest, he delivered a speech called The Negro and the Constitution. Like I Have a Dream, this speech examined whether the treatment of Blacks in America was consistent with American values. But unlike I Have a Dream, it did not locate those values in the Founding. “America gave its full pledge of freedom seventy-five years ago,” King said: in 1868, when the 14th Amendment was ratified. The Civil War and Reconstruction created a “new order,” he said, “backed by amendments to the national constitution.” It is these amendments, not the Declaration, that promised equality.

Roosevelt is a professor of constitutional law at the University of Pennsylvania Carey School of Law and the author of The Nation that Never Was: Reconstructing America’s Story. He is a great-great-grandson of United States President Theodore Roosevelt and a distant cousin of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The focus on Reconstruction gives us a different origin story. This one tells us our mission is to take up the struggle of a war for liberty and a remaking of society in pursuit of justice and equality. It is less reassuring, which is presumably why King abandoned it in I Have a Dream, seeking to enlist white moderates in his cause. But the allies he won turned out to be the“good people” of The Other America who sat by and counseled patience. And if this story is more divisive, it is also more true. In the Civil War, the U.S. issued an emancipation proclamation—in the Revolution, the British did. In the Reconstruction Constitution, the U.S. banned slavery—in the Founders’ Constitution, they protected it. And it is more inclusive; it locates our values not in documents written by white slaveowners but by those who fought to end slavery, blacks as well as whites.

This is a better story. And it is the story that King came back to. The day before his assassination in 1968, he spoke in Memphis, where sanitation workers were striking for decent wages and working conditions. King was ill that night and had asked a friend to speak in his place, but when he heard that hundreds of supporters were waiting to hear him, he went to the Mason Temple, took the stage, and spoke extemporaneously. I’ve Been to the Mountaintop starts by considering the question of what moment in human history King would like to live in. He considers some of the high points of antiquity—classical Greece and Rome, the Renaissance. He ignores the Founding entirely—the first moment of American history that gets a reference is the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. In the end, King says he would like to live just where he is, because “Something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And … the cry is always the same: ‘We want to be free.’”

We march for freedom, King told his listeners, and we will win if we stick together. He knew that freedom had a cost. “I may not get there with you.” But “we, as a people, will get to the promised land.” And he sent the audience out into the night with one final spur, invoking the great clash where white and black Americans fought together for the freedom of all. The last line of the last speech that King ever delivered is not from the Declaration or the Constitution. It is from the Civil War; it is the first line of The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

That is when our America was born, not with the Revolution and the Founding but with the Civil War and Reconstruction. The values we must carry forward are not those of Thomas Jefferson and the Framers of the Constitution; they are the values of Abraham Lincoln and the Reconstruction Congress. It is time for us to see this. It is time for us to join that march.

Kermit Roosevelt III is a professor of constitutional law at the University of Pennsylvania Carey School of Law and the author of The Nation that Never Was: Reconstructing America’s Story. He is a great-great grandson of United States President Theodore Roosevelt and a distant cousin of United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt.