“Ukrainians Are Defending The Values Americans Claim To Hold”, The Atlantic

By George Packer, Illustrations by Sergiy Maidukov, cover story, October 2022 Magazine

“You cannot just remain silent, you cannot remain still. You have to do something.”

Sergiy Maidukov

I had no business going to Ukraine. The country didn’t need another reporter to cover the war. Ukrainian journalists were already doing that much better than I could hope to, and so were plenty of foreigners. I had never set foot in Ukraine; I spoke neither of its languages; I was, my children told me, too old to be a war correspondent again. It would be completely pointless to get killed over there. But selfishness is an underrated motive among journalists. I told myself and others that Ukraine is the most important story of our time, that everything we should care about is on the line there. I believed it then, and I believe it now, but all of this talk put a nice gloss on the simple, unjustifiable desire to be there and see.

Because these motives seemed dubious, I looked for another way to be useful. Fortunately, a friend who had started an organization called Assist Ukraineneeded a courier to bring medical supplies to combat doctors in Lviv and Kyiv. The group sent me its contacts in Ukraine along with the supplies: a dozen junctional tourniquets and 40 pairs of holstered Raptor shears. The tourniquets, which came in khaki-colored nylon pouches and cost $350 each, looked like high-tech seat belts, with a compression pad on either end and a black rubber hand pump attached. Cinched and inflated under the armpits or around the hips, they’re designed to stop massive bleeding from major arteries where the body’s limbs join the trunk.

I also received a thick batch of homemade cards from a Ukrainian Catholic elementary school in Chicago, with messages of encouragement in English and Ukrainian and cheerful drawings of sunflowers and blue-and-yellow flags, to be distributed to random soldiers. Some of the schoolchildren were refugees, and many had relatives in the fight. I set out with exactly 50 pounds of donated supplies in a battered black suitcase that I’d been trying to lose.

Journalism that waves the banner of moral clarity makes me uneasy. Moral clarity can be blinding, and most subjects worth writing about are complicated. But a few things are morally clear: slavery, and genocide, and Russia’s attempt to destroy Ukraine. The suitcase full of medical supplies didn’t trouble my professional conscience. Nor did the Ukrainian flag my daughter and I painted on white paper and taped to our living-room window. Nor, I have to admit, did the money I sent to Razom, a Ukrainian American charity, and Come Back Alive, a volunteer outfit in Kyiv that provides nonlethal equipment such as night-vision goggles to Ukraine’s armed forces—though by now certain media ethicists would have barred me from going anywhere near Ukraine.

It’s absurd to approach this war from a position of neutrality. As a journalistic stance, neutrality is worthless, and usually spurious, because everyone is a partisan of some kind. Objectivity is different: the necessary effort, always doomed to fall short, of rendering reality exactly, like a carpenter striving for plumb, level, and square. What’s most crucial is independence: refusing to surrender your judgment of the truth for the sake of a political cause. Journalism doesn’t require an anesthetized moral faculty. It ought to be possible to want Ukraine to win this war and still tell what you see and hear there honestly.

After the Russian invasion, some commentators in the United States expressed a hope that Ukraine’s fight for survival might inspire Americans to rededicate ourselves to renewing our own democracy. Polls showed that a war in Eastern Europe was doing what the pandemic and global warming had failed to do: bring Americans together across partisan lines. You could find the same blue-and-yellow flag planted in the front yard of a ranch house in rural Maine and hung from a parking sign on my Brooklyn street. A country that hardly anyone here knew anything about seemed to offer a model of what we all believe to be good and want for ourselves—courage and freedom and unity. But the model had this power only because it was far away, and its flag’s colors weren’t ours.

In the days before my trip, I had a feeling of nausea that I recognized as dread. Not of the place I was going, but of the place I was leaving behind, of the let’s go brandon signs and the school-board showdowns and the next mass shooting, the prospect that our experiment in people coming from all over to run their own affairs together was finished. For the first time in my life, I felt hopeless about America. And because I have no transcendent beliefs, the loss of this earthly one left a void of meaning that made me sick.

Here was another motive—the strongest and most dubious of all. I wanted a gulp of Ukrainian air. I wanted to breathe its hope. What a thing to ask of people fighting for their lives.

“ah!” olesya vynnyk closed her eyes and inhaled the factory odor of new nylon from my black suitcase. “I can already smell the American tourniquets!”

We were standing by the open trunk of her Audi, on a cobblestone side street near the center of Lviv. Olesya is 31 years old (“same age as Ukraine”), a doctor in internal medicine, with long dark hair and black-framed glasses and skinny jeans and a droll smile. She woke up on the morning of February 24 to the Russian invasion. “My first thought,” she told me, “was that I have to do something.” She threw on some clothes and got in her car and started driving, with no idea where to go. She ended up in downtown Lviv, where she saw someone she knew in the bright-yellow jacket of Motohelp—a local civic group of first responders on motorcycles who reach the scene of accidents ahead of ambulances.

“Hey!” Olesya shouted to the Motohelp guy. “Let’s do something!”

By the next day she had set aside her medical practice and joined a group of doctors who were instructing the first civilian volunteers of the Territorial Defense Forces in combat medicine. Olesya helped organize Lviv’s Volunteer Medical Battalion, the unit that would receive the junctional tourniquets.

“That was the common idea, that’s who Ukrainians are,” she told me. “We just have to move and do something if we really need it. If the war comes to your home, you cannot just remain silent, you cannot remain still. You have to do something.”

On our way to the battalion’s compound, I asked what she was fighting for.

“Democracy, a new nation, survival—all together,” Olesya said. “This is a sacred war. It’s everything good against pure evil.” And Ukraine would win, she assured me. She was relentlessly optimistic.

At the compound—a children’s recreation center in a residential neighborhood—Olesya gave me a tour of classrooms where medical dummies lay bloody on the floor, and of improvised storage rooms stacked high with cardboard boxes of donated supplies. In the courtyard I met a young truck driver and an even younger graphic designer. At the start of the invasion, both of them had returned from jobs in Poland to volunteer.

I asked if they expected to win.

“We don’t even think about anything else,” the graphic designer said. “We need victory. Not-victory is not even in the mind. We have no choice.”

“It’s up to the outside world to help or not,” Olesya said. “But we will still win this war. It will be much easier with the help of the international friends. We’re trying to do a really huge thing: to build a new country while we fight the war. When we win, it will be beautiful.”

Didn’t they feel angry and tired?

“We are angry,” the graphic designer said. “We are tired.”

“We are doing this, but with a huge cost to the life of our soldiers,” Olesya said. “Sometimes it feels like too much. We will cry a bit later, after we win the war.”

Lviv, a lovely Habsburg town, had been turned into a refugee center and logistics hub, with tent camps in open fields, windows of 18th-century buildings sandbagged, and donated material piled up everywhere. It was all a little helter-skelter—no central department masterminded orders, inventory, or distribution. An ancient Greek Catholic church stored flak vests in a room off the entryway and boxes of boots in a loft next to the defunct organ. Father Andrew, the youthful priest, sometimes changed out of his black cassock into street clothes and drove military materiel some 700 miles across Ukraine, to the front. In the first 80 days of the war he had officiated at almost 70 funerals.

A whole society mobilized: This was my first, and most lasting, impression. The mayor of Lviv, Andriy Sadovyi, described Ukraine in crisis as “a beehive.” Nearly everyone I met had looked for something to do as soon as Russia attacked—some way to be useful without waiting for instructions from a higher authority. In Lviv a young behavioral scientist and serial entrepreneur named Sviatoslav Hnizdovskyi used his professional network to create the Open Minds Institute, beginning a campaign of phone calls to ordinary people in Russia, family members of soldiers fighting in Ukraine, with the aim of slowly puncturing the Kremlin’s bubble of lies. On the day the invasion started, Vira Krutilina, a sculptor, and Dmytro Levenko, a theatrical-lighting designer, went to volunteer at a local Territorial Defense post in Kyiv and were given instant training in the use of AK‑47s. Neither had ever fired a gun in their life, but within 24 hours they were standing on a rooftop in the north of the capital, scouting the streets below for the first Russian tanks. Vira described these early months of the war as “a magical time. People are connected with each other in a way we normally aren’t, and connected to people we would never be connected to.” She admitted that, on some level, she dreaded the day when the air-raid sirens would no longer go off.

The word Ukrainians use for all this spontaneous activity is self-organization.

“I think self-organization comes from an idea of community which is very deep in our culture,” Volodymyr Yermolenko, a philosopher and journalist, told me. “In Ukrainian we call it hromada. The idea is that politics is about horizontal relations between people and not about vertical relations of power.” He traced the political concept to a circle of 19th-century intellectuals in Kyiv, and the spirit of community even further back, to the self-governing Cossacks of the 17th-century steppe.

“I wouldn’t dig so far back as the Cossacks—maybe go back to the Soviet time,” Stanislav Lyachynskyy, an activist who works on projects to strengthen Ukrainian civil society, told me. This tradition of self-organization came from the “mutual networks of survival from the 1980s, when there was a deficit of goods, and from the ’90s, when the old economy collapsed.” Both Lyachynskyy and Yermolenko observed that Russia, from the czars through the Soviet Union to the revanchist reign of Vladimir Putin, has always ruled its vast empire of nations from an authoritarian center, with power strictly vertical. In Ukraine, where the struggle for an independent identity was repressed for centuries, suspicion toward central power runs deep.

In 2014, when Ukrainians in Kyiv’s Maidan rallied to overthrow their corrupt Russian-backed president, Viktor Yanukovych, pressure from below for sweeping reforms intensified—for the rule of law, against corruption. But the Revolution of Dignity was far from universally popular. Not even Russia’s subsequent annexation of Crimea and the eight-year separatist insurgency in the Donbas region could fully overcome the historical divisions in Ukraine’s conflicting pulls toward democratic Europe and autocratic Russia.

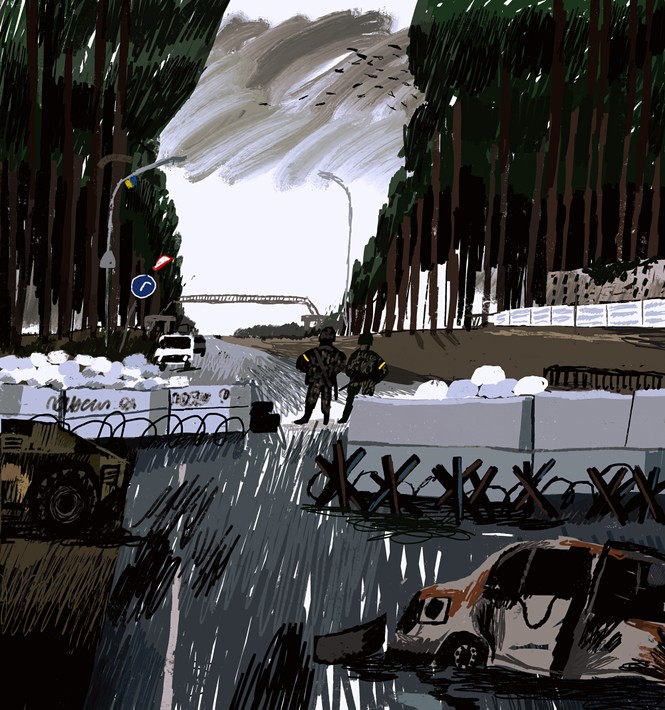

Then came February 24. From the first hours of the Russian invasion, self-organization characterized the response. Towns and villages spontaneously set up what Ukrainians call “block posts,” manned by armed civilians in Territorial Defense units. When Lyachynskyy drove his family three hours south from Kyiv to the relative safety of his sister’s house in central Ukraine, they passed 15 or 20 of these block posts. Some were built with sandbags, others with tires, lumber, concrete blocks, even steel anti-tank obstacles. “Every block post is unique,” Yermolenko said.

A number of Ukrainians blamed the local and national governments for failing to arm civilians in advance in towns—Bucha in the north, Kherson in the south—that fell immediately. Where early resistance succeeded, it was partly due to the ability of Ukraine’s armed forces and civilian defenses to seize advantages without waiting for orders from higher up. Where Russian troops became occupying forces, as in Kherson, they were faced with a local population that they couldn’t understand. “They didn’t know the real active leaders on the ground, so they pulled people off the street in huge numbers,” Serhiy Danylov, a researcher who spent years working in Kherson, told me. “The Russians asked the same questions of the activists they arrested: ‘Who is the organizer? Who is paying for all this? Who is behind it?’ They didn’t believe in spontaneous protest and self-organization.”

Later, when the war shifted to an artillery duel in the east, where Russia flattened entire towns and Ukrainian forces were badly outmatched, self-organization was less effective. But the Russian invasion has elevated the idea of hromada from local communities to the whole country. By killing Ukrainians regardless of their region or language or politics, Russia is helping forge Ukraine into something it’s never been—a national community.

Olesya vynnyk commandeered nine of the tourniquets, as well as the 40 pairs of Raptor shears. The next day, another volunteer would drive them across the country to troops on the Donbas front. My instructions were to take the remaining tourniquets to Kyiv.

Before going there, I spent a day following Olesya around Lviv’s hospitals. I was told not to take pictures, or even name the hospitals, for fear of identifying them as targets for missile attacks. (Russia has destroyed or damaged hundreds of medical facilities across Ukraine, along with schools, libraries, theaters, and cultural centers.) Some hospitals were still in decrepit, post-Soviet condition, but others were being renovated to European standards, with state-of-the-art cardiology facilities and MRI machines. All of this improvement was going on in spite of the fact that it could be obliterated in an instant.

One hospital I visited was caring for dozens of wounded soldiers and civilians from the east. The hospital director asked me not to interview the fighters: Most of them were suffering from trauma and extremely depressed to be stuck here, away from their units. So instead I went room to room with my batch of homemade cards. It was a rather mortifying errand. Soldiers in their underwear, lying or sitting on hospital beds in bare-bones rooms, faces bandaged, white tape wrapped around shrapnel wounds in their legs and arms, glanced up without interest or with resentment at a stranger intruding on their private pain. They took the cards I handed out and opened the envelopes, showing glimmers of curiosity. They tried to make sense of the handwritten scrawl, most of it in English, of Chicago schoolchildren. I left a few of them faintly smiling.

In a room with yellow walls and a view of the suburban hills there was an old couple, Ivan Yakovenko and Nataliia Sukhina, who had just been evacuated from a town in the Donbas called Popasna. Their house no longer existed, and neither did their town. At the start of the invasion they had waited too long to flee—“We thought it would be like 2014,” Nataliia said: “Some houses damaged, but not on this scale.” For two months they were trapped in their house, without electricity, windows shattered, caught in the cross fire of constant shelling. They lost all contact with their children and grandchildren, who lived on the side of town under Russian occupation. A 67-year-old neighbor was taken away at gunpoint and deported to Russia. Ivan, a retired factory worker, drove part-time for a funeral service, and for a few weeks he collected bodies around town that had begun to decompose.

Before dawn on April 26, a shell landed on their house and buried them in rubble. Popasna had by then become the small-scale Stalingrad that Russian forces created everywhere. The couple was dug out and evacuated to Lviv. They had no money, no clothes, nothing.

Ivan, bearded, missing most of his teeth, a flannel shirt hanging off his skinny shoulders, sat on a bed in utter bewilderment. “We don’t know where we’re going next,” he said. “There’s nothing to go back to.” The trauma had left his wife unable to walk, and she lay under a bedsheet from which a catheter extended. Her left arm was covered in bruises, her left hand was missing two fingers, and her cheeks were wet. But Nataliia was not too broken to fume. When I asked what she thought of Putin’s promise to “liberate” Russian speakers like them in the Donbas, her blue eyes hardened, the red in her cheeks deepened, and she answered, for the first time, in Ukrainian: “Let him drop dead. We had a good life without him.”

Ivan and Nataliia, like the soldiers separated from their units, were alone, and being alone and helpless rendered their suffering meaningless. Self-organization connected people to one another with a purpose that made the war more bearable. It shaped an expression that I associated with Ukrainian faces: open, direct, uningratiating, a little tough but on the verge of being amused—alive. People walked fast. Armed men and women in uniform were a natural part of the population, hardly separable from civilians, and it was strange to be constantly in their presence, on trains, in cafés, and feel no danger except from the sky. In America a uniformed soldier among civilians is a curiosity, and a young man with a semiautomatic weapon is not a welcome sight. I needed a few days to realize why a Ukrainian city felt somehow less tense than an American one: It was because you knew no Ukrainian was going to shoot you, and everyone you met was on the same side.

While I was with the wounded, Olesya disappeared to see a military friend who had suffered a serious head injury at the front. When she returned, her easy smile was gone. As we drove back to town, she played a music video that had been posted to YouTube in April by the armed forces—clips of badass military action set to a heavy dubstep score. The song’s title, and its refrain, was “Don’t Fuck With Ukraine.” Olesya, a devout Greek Catholic, apologized for the language but said she found the song helpful.

I had come from a country where the bonds of trust have been worn down to nothing, where earnest declarations about building a new country while winning a war can’t be swallowed without a heavy dose of irony, and where cynicism is a protective reflex against these losses. So, as an American, I had begun to question Olesya’s cheerful optimism. Yet almost every Ukrainian I met shared it: “We will win.” And also: “No compromise.”

After the hospital, as we drove through Lviv’s pretty, sunlit streets to the beat of “Don’t Fuck With Ukraine,” I understood a bit better. The song—Olesya called it “the music of war and marching”—made her feel brave and resolute. It was like that bit of bravado from the war’s first days, “Russian warship, go fuck yourself,” which had practically become a national motto, printed on posters and chocolate wrappers and inspiring a collectible stamp. Ukrainians need to be brave and resolute, because they face immense odds against winning and terrible consequences if they lose, and meanwhile every day brings crushing loss. There can be no compromise because the alternative, they’ve learned, is annihilation. Shouts of “Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!” might make certain European bureaucrats and American pundits smile with uneasy condescension, but Ukraine under invasion is not a place where the clever refinements of a detached intelligence have much use.

In “Radio Atlantic,” Jeffrey Goldberg and Anne Applebaum report on their journey to Kyiv to meet with Ukraine’s president:

In kyiv one night, I was invited to dinner by the Svystovych family. They were staying in the apartment of friends who had left at the start of the war. The Svystovychs’ home—in Irpin, the northern suburb that, along with Bucha, had been a front line of occupation and become the site of mass killings before the Russians were repelled—lay in ruins. Mykhaylo Svystovych was a business consultant and civic activist with unruly gray hair and a middle-aged belly and squinting eyes behind thick glasses. He had participated in every popular movement since the 1990 student hunger strike that helped lead to Ukraine’s overwhelming vote for independence from the Soviet Union. Myroslava, his wife, was a real-estate agent, with the wide cheekbones and long straight hair of so many Ukrainian women. She had once served briefly as Irpin’s mayor before being voted out (she said she was pushed out for standing up against corrupt land deals). Their son, Yaroslav, was 24 and studying IT. Their daughter, Lada, 22, was still recovering from a Russian bullet wound in her side; she smiled throughout the meal but didn’t say a word. The family also had two dogs, including a pointy-eared stray they’d adopted at the start of the invasion, and a black cat missing its left eye. The pets turned out to be the key to the story the family told me over borscht, lamb, rice, and Bison Grass vodka, while a television in the corner aired continuous war news.

In Irpin they had lived in two cramped rooms on the ground floor of a two-story complex. When the Russian invaders approached from Belarus, the Svystovychs decided to stay put, because the Ukrainian forces seemed to be holding their own. The Svystovychs didn’t want to abandon their elderly neighbors. And anyway, the family had no car.

Many Ukrainians I asked, like Afghans in Kabul just before the arrival of the Taliban, simply didn’t believe that the Russians would start a full-scale war. There’s a profound resistance to imagining the end of everything you know. Some people from the Donbas who had already fled the Russians once, in 2014, refused to run again. Some Ukrainians couldn’t imagine the brutality that lay in store for them until it was too late. “You always wait until you have only 15 minutes,” Stanislav Lyachynskyy, the civic activist in Kyiv, said. “You see the otherness of your flat, your world. You are still here, but your previous life is just faded away. And you have 15 minutes.”

By March 6, the Svystovych family had no power or water. That day, a shell exploded in the yard, 75 feet from their apartment. Myroslava was standing by the stove at the moment the kitchen window blew in and filled her hair with bits of glass. Mykhaylo had just taken a step back from the bedroom window, and shrapnel peppered the walls around him. A piece ricocheted off a wall into the bathroom and chipped the bathtub, just missing Lada. Given the tiny size of the rooms and the thousands of flying glass and metal fragments, it was miraculous that no one was hurt, except the cat, which took a piece of glass in the eye.

A few hours later a second shell landed in the yard, doing more damage to the building’s exterior. The apartment was now too cold for habitation, and the family spent the night with others in the basement of a jewelry shop. Even then, they didn’t intend to leave. But the next day they could find no veterinarians left in town. Lada insisted that they had to evacuate the wounded cat to Kyiv.

On the afternoon of March 7, the Svystovych family tried to get out of Irpin. Their phones were almost dead, so they didn’t know that Russian troops were only 200 yards away. The family split up into three evacuation cars driven by volunteers—Yaroslav with the stray, Mykhaylo with the other dog, and Myroslava and Lada with the wounded cat in a carrier. But on the way out of Irpin the women’s car left the convoy and ran straight into Russian troops. Suddenly the windshield exploded. Myroslava screamed for Lada to get down. The driver fell out through his door—he’d been shot—and the car rolled half a mile downhill until it slowed enough for Myroslava to jump out. She shouted for Lada to do the same, but the cat carrier was in the way and Lada had trouble moving—there was something heavy in her right side. When the car finally stopped, she managed to get out, bringing the cat with her.

Myroslava couldn’t reach Mykhaylo—his phone was dead—so she tried to call a friend. Russian troops, their faces masked, were approaching on foot. Myroslava cried out for help.

“Who are you calling?”

“My husband.”

A soldier took her phone and crushed it under his boot.

The Russians ordered Myroslava and Lada to walk to a nearby road where they were picked up by an evacuation car. By then it was clear that Lada had been shot. She was weakening fast, and at the Irpin River she had to be carried over the temporary wooden crossing that had replaced the blown-up bridge to Kyiv. Lada was taken by ambulance to a city hospital, where doctors repaired her perforated intestine just in time to save her life.

A few weeks later, Ukrainian forces pushed the Russians out of the area around Kyiv, and the Svystovych family returned to check on their apartment. It was in ruins, along with much of the suburb. Neighbors told them that Russians had defecated on the floors. One neighbor found the amputated leg of a Russian soldier in his house. He brought the leg to the local authorities, but no one knew what to do with it, so the neighbor wrapped it in plastic and left it between the bars of a fence. Eventually someone took the Russian leg away, as if this part of the tale had been invented by the Ukrainian native Nikolai Gogol himself.

As the family told their story over dinner and vodka, they kept exchanging glances and laughing, amazed and relieved at having survived the ordeal, and the two dogs prowled around the table for handouts, and the one-eyed cat dozed in a chair, and the TV news reported that the siege of Mariupol was ending, and there was an incongruous lightness in the room, even when Mykhaylo laid on the table a fistful of rust-colored, jagged-edged pieces of Russian shrapnel from the apartment in Irpin. He placed one in my hand. I have it beside me now.

The next day I accompanied Mykhaylo and his friend Serhiy Glynianyi, a former Irpin councilman, on a mission to bring supplies to elderly people in their town. On the road out of Kyiv, where sandbags and anti-tank obstacles marked the farthest point of the Russian advance on the capital, we stopped to buy groceries. One minute we were in a modern European supermarket, with a brightly lit cheese counter and shoppers unloading their carts at the checkout belts and cashiers efficiently scanning items. A few minutes later we drove into a cozy suburban neighborhood that had become a scene of destruction. Broken stucco walls, gabled roofs caved in, tan brick facades blackened by fire, wrecked furniture in rooms open to the sky, a pile of corrugated iron in a yard, someone’s car left by the roadside with flat tires and shattered windshields, its body riddled with bullet holes.

Every street was like this.

On some streets one house lay in rubble while its next-door neighbor 10 feet away was perfectly intact, as if the victims had been determined by some malevolent lottery. “It seemed like they had to hit one house in every neighborhood,” Ighor Glynianyi, Serhiy’s son, said when we stopped by his house. His neighbor’s house was in ruins, while his had sustained only light damage. “Keep away from the fields,” Ighor, a recruiter for Ukrainian technology companies, told us. “They mined everything—even children’s pianos and toys.” There were skull-and-crossbones warnings at the edge of the forest. Recently, an old man had ventured down a path into the woods and stepped on a mine.

We drove along Dostoyevsky Street. Someone had spray-painted black over the Russian author’s name on the sign.

Three old women were sitting in the yard outside Mykhaylo’s flat. He handed out bags of provisions and medicine, and the women kissed his hand. In the apartment, the food Myroslava had been preparing when the shell hit still lay scattered about the kitchen. Water was leaking from a broken pipe onto the floor. Mykhaylo ignored it. He had more errands. A bag with cooking oil and water for an old woman who was waiting for him in a veterinary office. Thyroid medicine for a younger woman we encountered on a shopping street. Pills for an old bald man in a tiny, sour-smelling seventh-floor apartment. Anatoly Sherstyuk had been unable to evacuate because his wife is paralyzed. He had been an artilleryman in the Soviet army, and now he had Russian shrapnel in his foot from a shell that landed nearby while he was cooking on an open fire in the yard. Limping to the door, he chuckled at the irony.

We crossed over into Bucha. According to Mykhaylo, the Russians had killed 300 people in Irpin—there were still unidentified bodies in the morgue and graves being discovered. In Bucha the number killed was more than 450. Both suburbs had become shorthand for Russian war crimes.

On a bench outside a high-rise complex I spoke with a Bucha councilwoman named Kateryna Ukraintseva. She had short black hair and tired green eyes, and she wore the green fleece of the Territorial Defense Forces. She’d spent the first two weeks of the invasion as a spotter on her rooftop, reporting the movement of Russian troops and helicopters that were landing at nearby Hostomel Airport, and guiding evacuation convoys. When the water was cut off, she and her neighbors drank melted snow. She told me that Bucha fell quickly, and that was why the physical destruction wasn’t as great as in Irpin, though the human losses were worse. When her activities were discovered, she went into hiding, and then escaped the town.

“We need Javelins,” she said, referring to American-made anti-tank missiles, “to cover Hostomel Airport.”

Did she think the Russians might come back?

“They might. You never know.” She smiled wryly. “We need the U.S. to do a bin Laden operation.”

It took me a moment to realize whom she intended as the target of the operation.

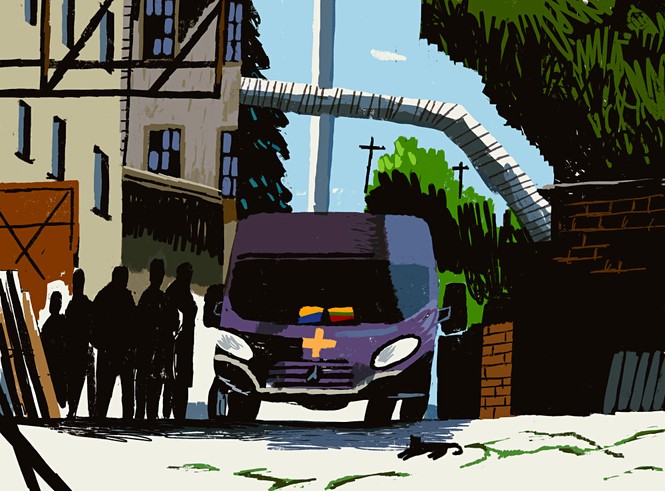

I spent the next day in another Kyiv suburb, Brovary, to the east. The villages around it had endured weeks of occupation. Special police investigators from Lithuania were filming a destroyed school to gather evidence of war crimes. Even the unoccupied neighborhoods were in ruins from random artillery fire. In one village a man showed me how his house had been spared thanks to the community library across the street, which had stood in a shell’s path and taken a direct hit. Its broken walls exposed a mass grave of books.

“These targets have no military value,” the lucky homeowner pointed out, superfluously.

After two days in Kyiv’s suburbs, buildings in rubble began to seem normal, while an intact street looked artificial, like a deceptively pretty painting, and the sight of a child anywhere around the capital was almost startling. Compared with Kharkiv or Mariupol, the scale of this destruction was fairly small. The cost of rebuilding Ukraine will be staggering—some estimates put it at $1 trillion—and so will the effort to revive its shattered economy. The Russian way of war is a form of shock and awe whose intended effect is not just to leave cities and towns uninhabitable and undefended, but to overwhelm the survivors and render them utterly passive, as if they are facing not a recognizable human enemy but a force of nature, or some kind of supernatural power, an impersonal god that destroys whatever it touches.

But one evening something happened that put me in a different frame of mind. I was walking back to my hotel along Khreshchatyk, the main avenue that runs through Kyiv’s Maidan. The streets were nearly empty as the 10 o’clock curfew approached. An air-raid siren began to wail. Few Kyivans paid the alarms much attention anymore, but I quickened my pace. I passed two women in the orange uniforms of city workers. At this hour, they were sweeping out the gutters. I suddenly realized that Kyiv’s streets were incredibly clean, with hardly a scrap of trash anywhere. A lot of effort went into keeping the city, with its broad squares and grand facades in pale blues and pinks and yellows, orderly and pleasing. Everywhere you looked, lilac bushes were in bloom—they were blooming all around the ruins of Irpin and Bucha, too, and along the embankments of the railroad tracks between Lviv and Kyiv—and chestnut trees were covered in shaggy white flowers, and beds of red and yellow tulips spread out around monuments. None of this was natural, any more so than the destruction that artillery and missiles rained down on innocent people going about their lives. Human hands had tried to ruin the city, and human hands were keeping the ruins beautiful.

I had heard that so many people wanted to help clear the rubble from Ukraine’s destroyed cities, wait lists were needed to organize all the volunteers. But somehow it was the sight of those two women sweeping the street just before curfew that brought home to me the obscene wrongness of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Here was a country with a tragic history that had at last begun to build, with great effort, a better society. What made Ukraine different from any other country I had ever seen—certainly from my own—was its spirit of constant self-improvement, which included frank self-criticism. For example, there’s no cult of Volodymyr Zelensky in Ukraine—a number of Ukrainians told me that he had made mistakes, that they’d vote against him after the war was won. Maxim Prykupenko, a hospital director in Lviv, called Ukraine “a free country aspiring to be better all the time.” The Russians, he added, “are destroying a beautiful country for no logical reason to do it. Maybe they are destroying us just because we have a better life.”

Shitting on the floor of a newly renovated house after killing or driving out its owners—that, in an image, is Russia’s war against Ukraine.

babyn yar, where the Nazis killed 33,771 Kyivan Jews on September 29 and 30, 1941, is a stretch of urban parkland cut through by a series of ravines that were once part of an immense pit. In 1976, after decades of silence, the Soviet Union built a monument there to “Soviet” victims of the Nazis. After independence, memorials to other victims—children, Romani, Ukrainian nationalists—were added to the site. The fact that most of the dead were Jewish is acknowledged only by a single monument in the shape of a menorah, placed by Ukrainian Jews in 1991. To this day Ukraine has not looked the Holocaust—and the collaboration of Ukrainians who participated in the mass killings—fully in the face.

In 2016, the Ukrainian government announced plans for a $100 million state-of-the-art museum and research center that would supposedly do justice to Babyn Yar. Much of the funding would come from Jewish oligarchs, who had ties to Russia. The first elements, by international artists such as Marina Abramović, were a travesty of narcissistic kitsch. Olena Styazhkina, a historian from Donetsk, told me that she saw the project not as an honest memorial but as Russian propaganda—a cynical attempt to highlight the crimes of the past as a way to suggest that present-day Ukraine remained anti-Semitic. The Russian-backed project would help buttress the falsehood that Ukraine was a neo-Nazi state, which became Russia’s chief pretext for invading.

On the street outside the unfinished research center, as if to remind visitors that innocents continue to be slaughtered here, were the remains of a fitness club and an ice rink—twisted steel and tangled wires, fallen branches and blackened tree trunks, all stinking of char—where, in the first days of the invasion, a Russian rocket had missed its intended target, the television tower across the road. Much more than the park’s smorgasbord of monuments, the bitter smell of things not meant for burning made me think of cruelty and death. In the woods at the far edge of Babyn Yar, a few hundred yards and 80 years away, a steep brown gash in the earth had the same effect.

I asked Alla Zamanska, a Jewish television director in her 60s, how Babyn Yar should be memorialized. “It has to be an empty place, with only a menorah where there’s a natural ravine,” she said, “and people can bring candles, and that’s enough.”

Alla lives with her husband, Mark Belorusets, who is also Jewish, in a narrow, book-filled apartment in central Kyiv. My friend with Assist Ukraine, the group that had given me the tourniquets, asked me to bring the couple some basic supplies—pain-management kits, catheters—as a way for them to thank the Kyiv hospital that had just removed part of Mark’s cancerous lung. He sat at the kitchen table, gaunt and fragile, with his bald head in his hands, while Alla served tea and pastries.

They had stayed here throughout the invasion. “I couldn’t have left,” Alla said, “knowing some people would be killed, some places destroyed in this city where I’m so attached.”

Alla exists only because her mother was evacuated from Kyiv to Tajikistan at the start of the German invasion; her father fled Ukraine to serve with the Red Army in the Arctic Circle. By the vagaries of Soviet history, Alla had been born in Siberia and spoke Russian. “From the very moment of independence in 1991,” she said, “Ukrainian anti-Semitism has started to disappear.”

“Diminish,” Mark corrected.

“Face-to-face it continued, but not from the state. No Jews could work for the U.S.S.R.-era state radio. But our daughter worked there.”

“Ukraine has a historical anti-Semitism,” Mark insisted.

Alla explained that each republic in the Soviet Union had a “titular nation”—the dominant ethnic group that gave the republic its name. Until very recently, Ukrainian nationalism had been based on Ukrainian ethnicity. It was strongest in the west of Ukraine, and it excluded Jews, Poles, Tatars, and Ukraine’s second-largest ethnic group, Russians. The Revolution of Dignity in 2014 began to change the idea of the nation’s identity from an ethnic to a civic one. “During Maidan, the first person killed was ethnic Armenian; the second was from Belarus,” Alla told me. “This somehow erased the Soviet idea of the ‘titular nation.’ ” In 2019, Ukrainians voted overwhelmingly to elect a Jewish president.

Ukraine’s democratic transformation is far from complete, but the invasion greatly accelerated and was, in a way, motivated by it. The idea of a nation that includes all of its citizens as equals directly threatens Putin’s Russia—as a model of a post-Soviet democracy, a challenge to Russian imperialism, and a refutation of the “neo-Nazi” charge with which Putin justified his invasion. Ukraine’s far right has a much greater presence in Russian propaganda than in Ukrainian politics. Right-wing nationalists won barely 2 percent of the vote in the 2019 parliamentary election, far lower than their shares in most European countries; the paramilitary units that arose with the start of the war in 2014, such as the notorious Azov Battalion, have mostly assimilated into the country’s regular armed forces.

It is impossible to know what public opinion is like in the occupied regions, but Russian behavior can hardly have won the hearts and minds of Ukraine’s Russian speakers in the east and south. Ukraine’s present unity is unprecedented, but war—always intolerant of complexity and ambivalence—is pushing Ukrainians to construct an identity that is simpler than the country’s history. The war will not resolve the abiding question of what it means to be Ukrainian.

just outside the wall of Lychakiv Cemetery in Lviv, where military and cultural heroes from history are buried, there’s a field with dozens of fresh graves dug since February: mounds of dry dirt covered in flowers, small bottles of colored glass, crosses, portraits and names of the dead. here rests soldier kmitb yaroslav romanovych 04.06.2004–05.04.2022. eternal memory. They are decorated with the ubiquitous blue-and-yellow flags, as well as a few red-and-black ones. These are the flags of the armed wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, an insurgent movement of the ’30s and ’40s in what is now western Ukraine, which fought against first Polish and then Soviet rule. A stone’s throw from the new graves, actual members of that movement lie buried against the cemetery wall.

Their leader was a radical nationalist named Stepan Bandera. In 1941 he and his fighters collaborated with the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. But when the OUN sought Hitler’s blessing for an independent and ethnically pure Ukrainian state, Bandera was arrested by the Nazis and spent most of the rest of the war in a concentration camp near Berlin, while in western Ukraine his insurgent army massacred Poles and Jews. Years after the war, Bandera was murdered by a KGB agent in Munich. By almost any definition he was a fascist, but he still has a passionate following among some western Ukrainians, who have erected Bandera statues and museums throughout the region. At the same time, he’s a useful tool for Russian propaganda.

Alla Zamanska was the one who put me in touch with Vira Krutilina and Dmytro Levenko, the sculptor and lighting designer. They worked together at a cultural center named after Les Kurbas, a theater director of the ’20s and ’30s who belonged to the Executed Renaissance—a generation of anti-Stalinist writers and artists in Ukraine who were murdered by the Soviet regime. A play of the same name had just been performed in the center’s basement—for safety reasons—in a room now crowded with boxes of food that five young actors were busily assembling into delivery bags. Outside, Vira and Dmytro were having a smoke on a small fenced-in terrace. They were surrounded by a dozen identical plaster busts, made by Vira, of a man with a weak chin, stern frown, and fanatically staring eyes. I immediately recognized Stepan Bandera.

Smiling, slouching, hands in the pockets of her torn and plaster-spattered jeans, Vira didn’t seem like a fascist. When I asked about Bandera’s views, she had little to say. To her he was just a symbol of resistance—the plaster equivalent of “Don’t Fuck With Ukraine” and “Russian warship, go fuck yourself.” The more Russia invoked Bandera as a pretext for “de-Nazifying” Ukraine, the more popular he became. Vira could hardly keep up with requests from Territorial Defense units. The busts were a contribution to the war effort.

When I mentioned Vira’s Bandera project to Alla, she wasn’t bothered. “He’s no longer seen as a historical person,” she said. “He’s become a myth, made by Russia.”

Babyn Yar and Bandera are bound up together in Ukraine’s unresolved history. Decades of Soviet repression, then decades of a chaotic and contested independence, made it almost impossible to grapple openly with their meaning. The Russian invasion brought a surge of civic feeling, but along with solidarity and self-organization came a burning hatred of all things Russian, whether Putin or Pushkin, and open contempt for the Russian people, who are widely regarded as Putin’s slaves. Streets and landmarks named after famous Russians have been rechristened, the special status accorded Russian literature is fading, and in Kyiv, a largely Russian-speaking city (in the Soviet system, Russian was the language of career advancement), Ukrainian is becoming dominant, especially among the young.

Olena Styazhkina, the historian from Donetsk, fled the Donbas amid heavy shelling not long after the start of the pro-Russian insurgency in 2014. She asked herself how, if she lost and regained consciousness, she would know she was safe: “If the people around me spoke Ukrainian.” She called Russian, her native tongue, “a weapon of death and blood. I don’t want to speak Russian anymore.” Instead she has taught herself to speak and write in Ukrainian. Styazhkina predicted that Russian would gradually disappear from Ukraine.

I wondered how postwar Ukraine would make a place for its uprooted, its occupied, its citizens with lingering attachments to Russia. Would people who had survived the Russians in Donetsk or Mariupol come under suspicion as collaborators? Would there have to be—as one Ukrainian told me—large population transfers, questionable Ukrainians sent to Russia and others resettled in their place, like in the old days of the Soviet Union? Then what would be left of the democratic struggle that continued alongside the war?

None of these questions—which are about the country’s past as well as its future—can be answered while Ukraine is fighting for survival. But I took some hope from the responses I heard whenever I asked what the war was about. “From the Ukrainian perspective, and also from the Russian perspective, this is certainly not about religion, not about a piece of land, not about natural resources,” Oleksandr Sushko, the executive director of the International Renaissance Foundation, an organization promoting democracy in Ukraine, told me. “Normally war is about something like this. But here it is not. It is not even about the ethnicity. But it becomes very clear what this conflict is about if you talk about democracy to the people who represent different sides of this war.” Someone on the Russian side, he went on, would tell you that democracy was a manipulative fairy tale. But “when you ask a Ukrainian what this battle is about, he will tell you this is not about ethnic belonging but this is about freedoms, free choice, and the right to determine your life.”

It wasn’t hard to meet American volunteers in Ukraine. In a hospital corridor in Lviv I ran into an anesthesiologist and Navy veteran from Chicago named Rom Stevens. In a cemetery in Irpin, where the civilian victims of Russian atrocities lay buried alongside fallen soldiers in rows of fresh graves, I met a retired paratrooper from Portland, Oregon, named Paul Wall; the International Legion had declined to admit him, so he was driving supplies to Ukrainian troops on the Kherson front. On a long train ride I fell into conversation with a former Green Beret from Texas named Ramiro Carrasco Jr., who had just spent 10 weeks training Ukrainian snipers at a base outside Kyiv. These men were in their 50s and 60s. They had left behind families and jobs, and paid their own way to Ukraine.

The reasons they gave for coming were simple and personal. When Ukraine didn’t fall at the start of the invasion, Carrasco thought: I’m here sitting in my beautiful home watching this on TV, and they’re over there fighting to save their home. “I needed to go,” he told me. Stevens had been about to embark on a two-month sailing trip with a Navy buddy when they looked at each other and said: “We can’t go sailing when people are fighting and dying and we can do something to help.” Unlike humanitarians, these men had chosen sides. Europe seemed to have something to do with it—they didn’t go off to risk their lives on behalf of Ethiopians or Yemenis. “Wars in Africa—we don’t really assimilate them,” Wall said. “But I lived in England, it’s Europe, we’re all brothers.” Racial identity has played an undeniable role in the outpouring of Western support for Ukraine, and perhaps it tarnishes the value of the support. All of us should care more when those doing the dying aren’t blond-haired and blue-eyed or parking a bike share as the missiles explode.

But the motives of these men were, broadly speaking, political. A tyrannical Goliath was trying to kill a democratic David. That’s why Ukraine was worth the risk. Anyone with a human heartbeat who came and saw knew it. “They’re fighting for an ideal,” Stevens said: to “determine their own government, their religion, their culture.” Carrasco put it in more basic terms. “Slaves can never defeat free people—it can never happen,” he said. “Putin made a big mistake. He didn’t know these people. Once a man tastes the taste of freedom, he won’t let anyone take it from him.”

I didn’t know what these men thought of American politics, and I didn’t want to know. Back home we might have argued; we might have detested each other. Here, we were joined by a common belief in what the Ukrainians were trying to do and admiration for how they were doing it. Here, all the complex infighting and chronic disappointments and sheer lethargy of any democratic society, but especially ours, dissolved, and the essential things—to be free and live with dignity—became clear. It almost seemed as if the U.S. would have to be attacked or undergo some other catastrophe for Americans to remember what Ukrainians have known from the start.

Volodymyr Rafeyenko, one of Ukraine’s most important novelists, fled west to Kyiv from his hometown, Donetsk, in 2014; in March he had to flee west again, this time from his temporary home in a friend’s cottage in Bucha. Rafeyenko has lost almost everything to Russia’s war. “It’s a bad idea to have to face invasion in order to remember values,” he told me when we met in Ternopil, his latest dwelling place. “Not recommended by those who experience it.” He added that, by arming Ukraine, Americans might regain the values they’ve lost without having to endure war. Rafeyenko was offering democratic renewal at a reasonable price.

But Ukraine can’t solve America’s problems. We wouldn’t know what to do with their values, and they don’t need ours. What Ukraine needs is our weapons.

The U.S. has provided just enough of them just fast enough to keep Ukraine alive, but not enough to give it a chance of winning. For months, the Biden administration, not wanting to provoke Russia, delayed sending long-range precision rocket launchers that Ukraine desperately sought. The administration finally agreed to send the equipment, and it arrived in late June, but soon after that Russia achieved a breakthrough in the Donbas, seizing all of the region of Luhansk and much of Donetsk. With the help of the new weapons, Ukraine began to turn the tide, but the needless delay had a high cost in lives, territory, infrastructure, and momentum.

before i left ukraine, Olesya Vynnyk put me in touch with her friend Ighor Kholodylo, a paramedic and sergeant in the National Guard. We met outside his battalion headquarters and went to have coffee at a nearby hole-in-the-wall. He had a trim salt-and-pepper beard and keen eyes, and was about to return to the front after two weeks off. I gave him the last three tourniquets.

“This is an artillery war,” Ighor said. “They have 220-millimeter shells; they can cut trees in half. I’ve been looking for these for such a long time.” He met my eyes. “We lost troops because we didn’t have these.”

I don’t know if Ukraine can win this war, but I know it must. Putin’s Russia is committing crimes that have not been seen in Europe since Hitler and Stalin—leveling cities, terror-bombing civilian populations, creating millions of refugees, using rape and torture to break the will of those under occupation, separating families, detaining and interrogating at least 1 million Ukrainians and sending many to far-off internment camps, preparing to annex entire regions, erasing their language and culture, burning crops, using vital food and energy supplies to blackmail the world. If Western leaders are too afraid of Putin and their own voters to stop him and punish him for these crimes, he’ll know that the West is as weak and pleasure-seeking as he’s always believed. He’ll go on taking more of Ukraine, and then the region, in his quest to be another Peter the Great. The anti-Western, antidemocratic partnership that China and Russia proclaimed at the Beijing Olympics will look like a map of the 21st century. Authoritarians in Ankara and Tehran and Beijing will understand that history is on their side. The much-abused “rules-based international order”—the idea that might does not make right—will no longer stand for anything, not even hypocrisy.

But if Ukraine can push Russia back at least to the February 24 borders, deplete Putin’s military machine, keep Russia sanctioned and isolated, avoid a split in NATO, and retain the support of Western publics, then the idea that human life and freedom have value will be strengthened everywhere. Declining democracies won’t suddenly come off oxygen, but Ukraine will stand as an example for people around the world who refuse to accept a future of brutality and lies.

But I won’t pretend that these geopolitical arguments are my main reason for wanting Ukraine to win. Instead it’s Olesya Vynnyk I’m thinking of, Ivan and Nataliia, Lada and her family and pets, Alla and Mark, the cleaning women in orange uniforms. I can’t stand the idea that, after so much loss, they might lose everything. It would be so unfair.

This article appears in the October 2022 print edition with the headline “On Democracy’s Front Lines.”