Issue of the Week: War

Biden’s Surreal and Secretive Journey Into a War Zone, The New York Times, 2.20.23

Today in the U.S. is the President’s Day holiday and today the president of the United States, Joe Biden, astounded the world and created history in a new way by secretly travelling to Kyiv, Ukraine.

The story follows in the two front page stories in The New York Times and reports from CNN and BBC News:

“Biden’s Surreal and Secretive Journey Into a War Zone”

Peter Baker and

President Biden traveled covertly to the besieged Ukrainian capital of Kyiv, hoping to demonstrate American resolve to help defeat the Russian forces that invaded a year ago this week.

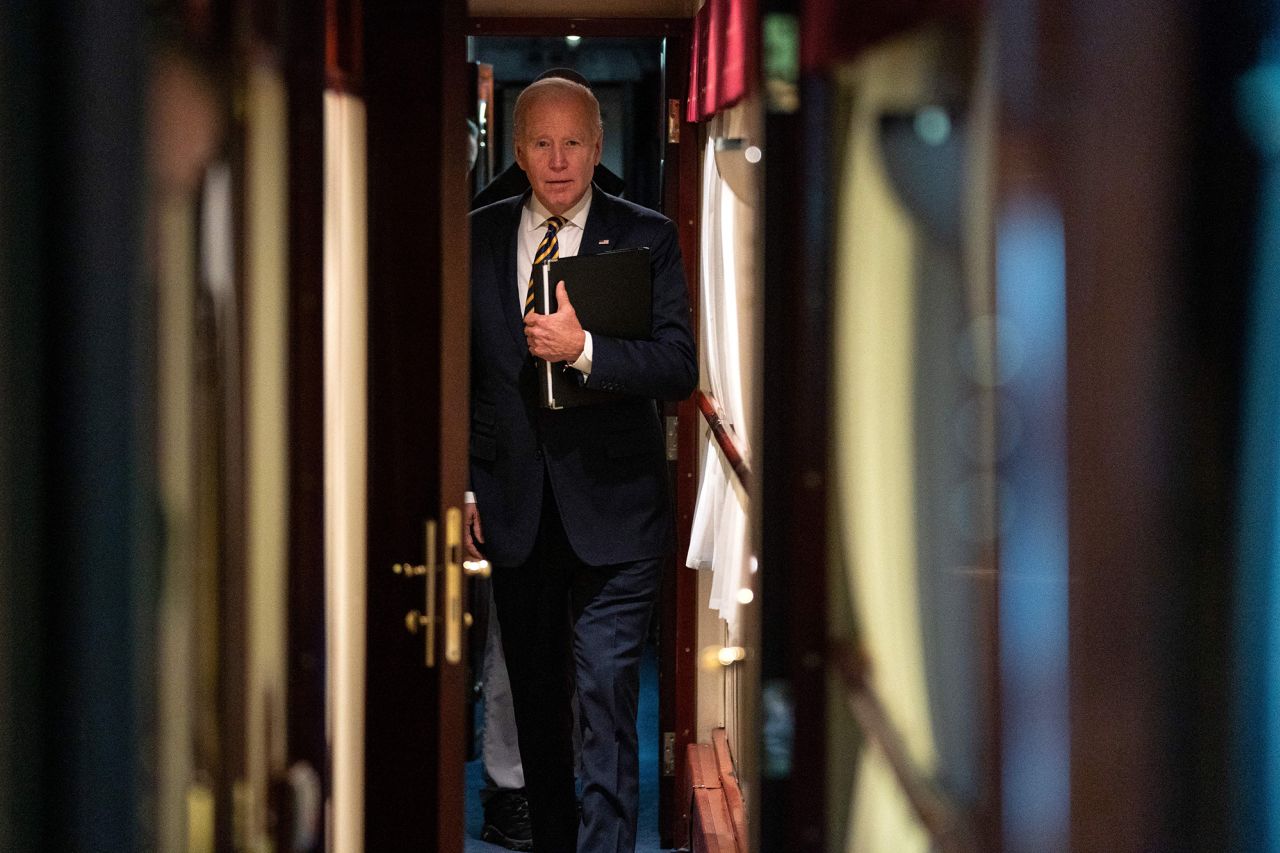

WASHINGTON — As the train rumbled across the Ukrainian countryside through a long night, the view outside the window left little to see, just the occasional streetlight or shadows of buildings in the distance. But neither could those watching the train go by see who was inside, nor would they likely have guessed had they stopped to wonder.

Huddled aboard the anonymous train were President Biden and a skeleton team of advisers accompanied by armed and edgy Secret Service agents, embarking on a secret mission to visit Kyiv. As far as the world was concerned, Mr. Biden was back in Washington, home for the evening after a date night at an Italian restaurant.

In fact, he was on a journey unlike any other taken by a modern American president.

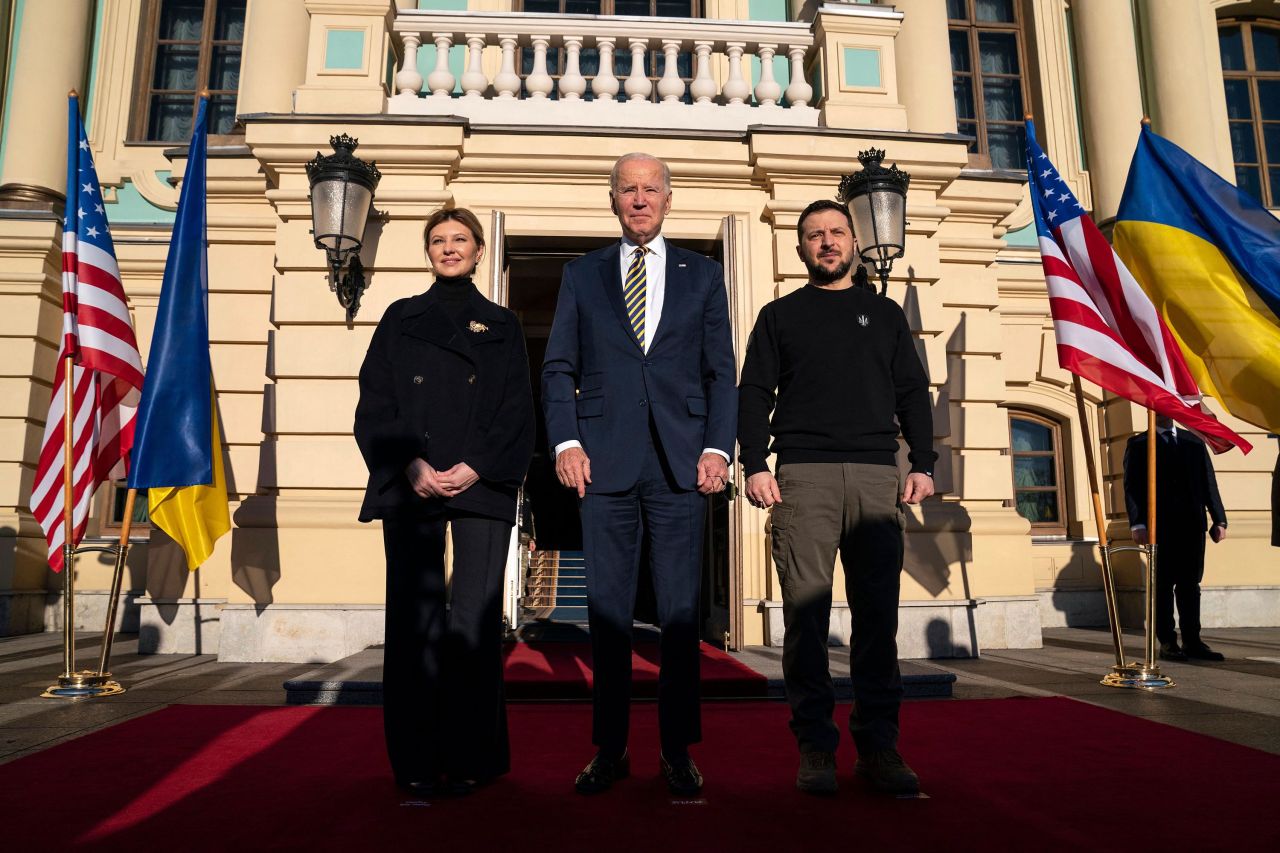

In an audacious move meant to demonstrate American resolve to help Ukraine defeat the Russian forces that invaded a year ago this week, Mr. Biden traveled covertly to Kyiv to meet with President Volodymyr Zelensky and promise even more weapons for the country’s defenders. The visit produced an indelible image of the two presidents striding to a memorial for fallen soldiers in broad daylight even as an air-raid siren blared, a show of defiance of Moscow quickly beamed around the world.

“I thought it was critical that there not be any doubt, none whatsoever, about U.S. support for Ukraine in the war,” Mr. Biden said during his five hours on the ground in Kyiv before leaving again. He was speaking, in effect, not just to President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia but to fellow Americans back home doubting his decision to invest so deeply in Ukraine’s war. “It’s not just about freedom in Ukraine,” he said. “It’s about freedom of democracy at large.”

Never in Mr. Biden’s lifetime had a president ventured into a war zone that was not under the control of American forces, much less on a relatively slow-moving locomotive that would take nine and a half hours to reach its destination. During that time, he was potentially exposed to circumstances beyond the control of the hypervigilant security phalanx that normally seeks to shield a commander in chief from every conceivable physical danger and minimize his time outside a hardened shelter.

For much of the past year, in fact, most of the people around the president resisted any urge to go, on the assumption that it was too risky. But nearly a year after the Russian invasion, with Ukrainian troops faring far better than anyone expected at the start and other American and European leaders having made the trip, Mr. Biden and his team gambled that he could get in and out safely.

The State of the War

- Biden Visits Kyiv: President Biden traveled covertly to the besieged Ukrainian capital, hoping to demonstrate American resolve and boost shellshocked Ukrainians. But the trip was also the first of several direct challenges to President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia.

- Portending a Global Rift: Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken said that China is strongly considering giving military aid to Russia, a move that would transform the war into a struggle involving three superpowers.

- A Russian Mole in Germany?: A director at Germany’s spy service was arrested on suspicion of passing intelligence to Russia. German officials and allies worry just how deep the problem goes.

“Of course there was still risk, and is still risk, in an endeavor like this,” Jake Sullivan, the president’s national security adviser, told reporters by phone from the train as it departed Kyiv for the return trip to Poland. “And President Biden felt that it was important to make this trip because of the critical juncture that we find ourselves at as we approach the one-year anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.”

It was a long journey and a surreal one. This was not how Mr. Biden was used to seeing Ukraine. He visited six times as vice president — three times in a six-month stretch — arriving in an American jet, gazing out the window in daylight to take in the sights of Kyiv from above. Now he was sneaking in under cover of darkness, arriving shortly after sunrise.

The trip had been in the works for months, aides said, as just a trusted few officials at the White House, Pentagon, Secret Service and intelligence agencies weighed the threat assessments. In meetings, Mr. Biden focused on the risk his visit could pose to others, not himself, one aide said.

Finally, the decision came to a head on Friday, when the president gathered with a handful of top advisers in the Oval Office and consulted with others by phone. He opted to go.

Mr. Biden was already set to travel to Poland for the anniversary. Often when presidents make secret stops in uncertain locations, the visits are added to the end of an existing trip. In this case, the White House decided to put it on the front end in hopes of keeping the secret.

The president played his part in the ruse. On Saturday evening, he and Jill Biden went to Mass at Georgetown University, then stopped by the National Museum of American History and finally went out to dinner at the Red Hen restaurant, where they enjoyed the rigatoni, widely considered the best in the nation’s capital. When the couple arrived back at the White House, most people might have assumed they were in for the night.

But a few hours after midnight, Mr. Biden was spirited out of the mansion and taken to Joint Base Andrews in the Maryland suburbs, where a small coterie of aides, security agents, a medical team, a White House photographer and two journalists awaited him.

The two journalists, Sabrina Siddiqui from The Wall Street Journal and Evan Vucci from The Associated Press, had been summoned to the White House on Friday and sworn to secrecy. They were told to wait for further information in an email whose subject line would read: “Arrival instructions for the golf tourney.”

The two-person journalism pool was a radical departure from even other security-sensitive presidential trips, when the usual complement of 13 reporters and photographers was taken. But it would not be the only unusual feature of the trip.

Since Abraham Lincoln rode to the front lines outside Washington to watch battles in Northern Virginia during the Civil War, no sitting president has gotten that close to combat. Franklin D. Roosevelt visited North Africa; Lyndon B. Johnson went to Vietnam; Bill Clinton toured the Balkans; George W. Bush and Barack Obama traveled to Iraq and Afghanistan; and Donald J. Trump went to Afghanistan.

But in all those cases, they went to countries or areas under control of American forces or after hostilities had eased. In this case, the United States military would not be present in Ukraine, nor would it control the airspace. American military planes were spotted hovering in eastern Poland near the border during the trip, but officials said they never entered Ukrainian airspace out of concern that it would be taken as the sort of direct American intervention that Mr. Biden has avoided.

Arriving at Andrews on early Sunday morning, the two journalists surrendered their phones, not to be returned for 24 hours. They were taken not to the usual blue and white Boeing 747 designated as Air Force One when the president is on board but to an Air Force C-32, more typically used for domestic trips to airports with shorter runways. The plane was parked in the dark next to a hangar with shades drawn.

Mr. Biden arrived about 4 a.m., and the plane took off at 4:15 a.m. for the flight across the Atlantic. Mr. Biden was joined by a handful of aides — Mr. Sullivan; Jen O’Malley Dillon, a deputy chief of staff; and Annie Tomasini, the director of Oval Office operations. The plane touched down at Ramstein Air Base in Germany at 5:13 p.m. local time, where, with its shades down, it was refueled before taking off again at 6:29 p.m. It then made its way to Rzeszów-Jasionka Airport in Poland, landing at 7:57 p.m.

Mr. Biden was put in a motorcade with roughly 20 cars and driven without sirens for about an hour along a mostly empty highway to the small city of Przemyśl and taken to the train station where many thousands of refugees have arrived from Ukraine over the past year. Arriving at 9:15 p.m., the travelers found few people there and the stalls closed.

The motorcade pulled right up to a mostly purple train, with several cars painted blue with a yellow stripe along the middle to resemble the Ukrainian flag. Rarely does a president ride in any vehicle other than those of the Secret Service or American military, but flying into Ukraine is not deemed safe.

The train pulled away from the station without ceremony at 9:37 p.m. and crossed the border into Ukraine around 10 p.m. The White House was so intent on keeping the secret that it lied to reporters back in Washington. About four hours after Mr. Biden crossed the border into Ukraine, his office back in Washington issued a public schedule falsely stating that the president was still in the nation’s capital and not planning to leave for Europe until Monday evening.

Dressed in casual clothes, Mr. Biden had a hard time sleeping during the long train ride, according to a senior official who asked not to be identified describing the trip. The president spent the ride recalling his previous trips to Kyiv, including a speech to the Ukrainian Parliament and his remarks on his final trip in 2017. He read a briefing memo on the history of Kyiv back to its founding and reflected on his history with the city.

Talking with aides, Mr. Biden recounted his telephone call with Mr. Zelensky on Feb. 24 last year as Russia’s invasion began, marveling about how the Ukrainian leader told him at the time that he was not sure when they would speak again. Now, Mr. Biden mused to aides, here they were a year later about to meet face-to-face in Kyiv.

After the all-night trip, the train pulled into Kyiv-Pasazhyrsky station at 8 a.m. local time. The platform had been cleared. On a sunny day with blue skies and a brisk chill in the air, Mr. Biden disembarked, now wearing a blue suit with a tie featuring Ukrainian colors. He was greeted by Bridget A. Brink, the American ambassador.

“It’s good to be back in Kyiv,” he said.

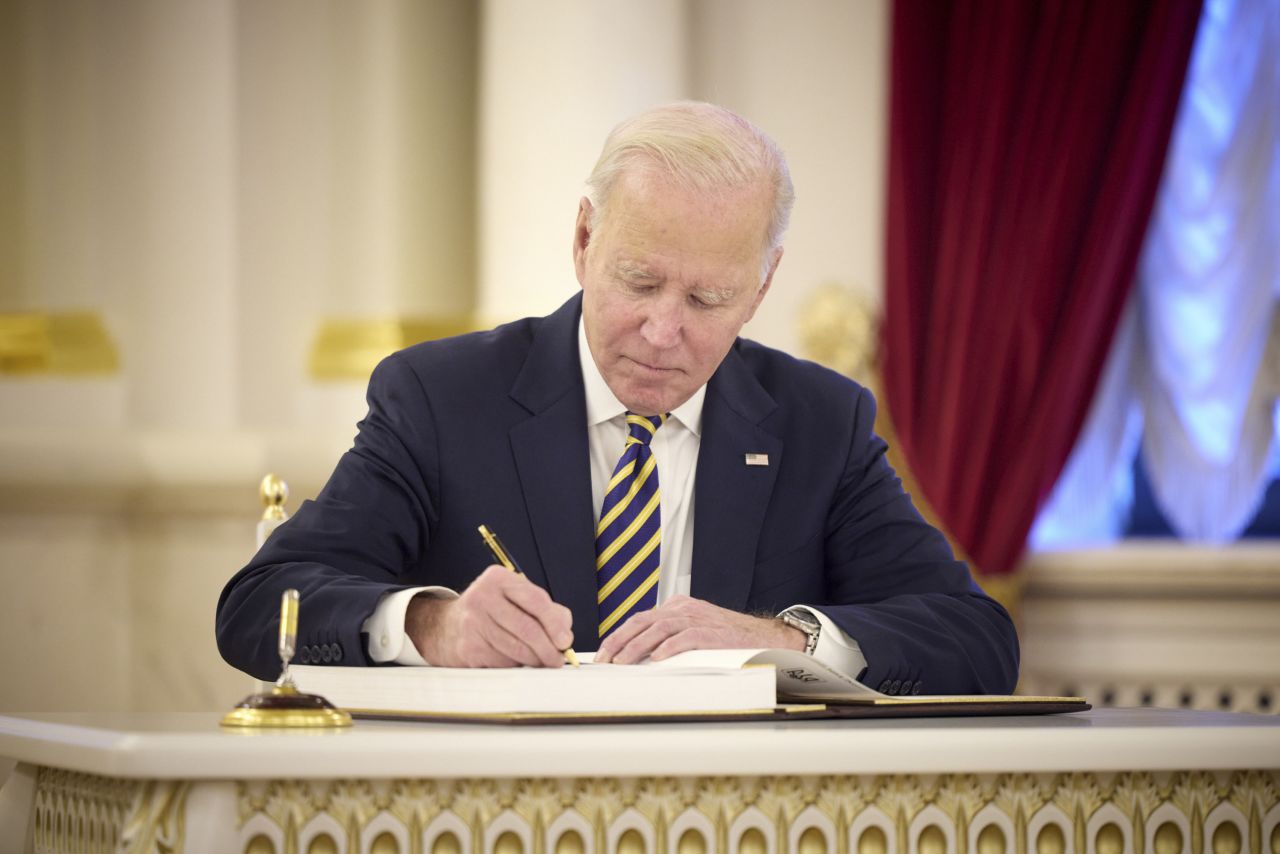

During his five hours in the city, he met with Mr. Zelensky at Mariinsky Palace, joined him in laying a wreath at the Wall of Remembrance at St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery and stopped by the United States Embassy to meet with its staff.

Then he headed back to the same train station, departing at 1:10 p.m. On the long meandering train ride back to Poland, the senior official said the president issued a series of directions on military, economic and diplomatic areas to help Ukraine. He was seized with the meetings he had just had. Once again, he could not sleep much.

He arrived at the Przemyśl Główny station at 8:45 p.m. local time, and he headed back to the airport for a flight to Warsaw, where he will deliver a speech on Tuesday. His mind, aides said, remained on his last stop.

“Kyiv,” he had said before leaving, “has captured a part of my heart, I must say.”

Peter Baker reported from Washington, and Michael D. Shear from Warsaw.

Peter Baker is the chief White House correspondent and has covered the last five presidents for The Times and The Washington Post. He is the author of seven books, most recently “The Divider: Trump in the White House, 2017-2021,” with Susan Glasser.

Michael D. Shear is a veteran White House correspondent and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner who was a member of team that won the Public Service Medal for Covid coverage in 2020. He is the co-author of “Border Wars: Inside Trump’s Assault on Immigration.

“In Biden’s Unannounced Visit to Kyiv, a Preview of an Increasingly Direct Contest With Putin”

David E. Sanger and

The vastly different world views of President Biden and President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia will become vividly apparent in a rare split-screen moment on Tuesday.

David Sanger attended the Munich Security Conference over the weekend and is covering the president’s Warsaw trip. Anton Troianovski covers Russia and reported on Vladimir V. Putin’s descent into authoritarianism.

WARSAW — President Biden’s sudden appearance in Kyiv’s presidential palace on Monday morning was intended first as a morale booster for shellshocked Ukrainians in the midst of a bleak winter of power outages and a bitter war of attrition.

But it was also the first of several direct challenges on this trip to President Vladimir V. Putin, who a year ago this week believed the Ukrainian capital would become Russian-controlled territory again in a matter of days, moving Mr. Putin closer to his ambition of restoring the empire of Peter the Great.

“Putin’s war of conquest is failing,” Mr. Biden declared from the palace, his very presence there, alongside President Volodymyr Zelensky, meant to symbolize Russia’s failure to take a capital that today remains brimming with life, its restaurants overflowing even as warning sirens blare.

“One year later,” he said, “Kyiv stands. And Ukraine stands. Democracy stands.”

The war in Ukraine is about power and the principle of territorial sovereignty, and whether the Western-designed global order that Americans thought would prevail for decades will, in fact, survive new challenges from Moscow and Beijing. But it is increasingly a contest between two aging Cold Warriors, one 70 years old and another who just turned 80, who have been circling each other for years, and now are engaged in everything short of direct battle.

On Tuesday the vastly different world views of these two leaders will become vividly apparent in a rare split-screen moment. They will both deliver speeches, several hours and 800 miles apart, vowing to stick with the war until the other retreats. Mr. Putin will go first, marking the first anniversary of his ill-fated invasion with what, by all indications, will be a renewal of a strategy that has already led to 200,000 Russian casualties, by British and American estimates, and as many as 60,000 Russians killed.

Mr. Putin will make the case anew that he is not only saving Ukraine from “Nazism,” but saving Russia itself from being overrun by NATO — a claim that seems ridiculous to Europeans but that has become a rallying cry in Moscow. If the past year is any guide, he is almost certain to cast his war as a battle for the restoration of Russia’s historic lands. American intelligence officials say they are picking up indications that he may soon mobilize more Russians into the military, adding hundreds of thousands to the 300,000 already called up.

Hours later, from Warsaw’s ancient Royal Castle, on a hill over the Polish capital, Mr. Biden is expected to build on the case he made in Kyiv on Monday morning, that in the battle between democracy and autocracy, the former has emerged the winner of the first year of what promises to be a long conflict.

Mr. Biden was in Kyiv on Monday for less than six hours before the Secret Service whisked him out of the city. (Notably, the White House informed the Kremlin of Mr. Biden’s impending visit before the president arrived, not as a diplomatic courtesy but for what Mr. Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, called “deconfliction purposes” — essentially, to avoid a Russian strike, accidental or otherwise. Mr. Sullivan added, “I won’t get into how they responded.”)

The covert nature of the Kyiv visit, and the vastly different world views the speeches will represent, underscore the degree to which the battle between these two men has echoes of exactly what Mr. Biden said he wanted to avoid: a replay of the worst days of the Cold War.

. . .

“Months of planning and days of secrecy led to Joe Biden’s historic trip to Kyiv”

By and , CNN, February 20, 2023

Warsaw, Poland CNN —

Around 7 p.m. ET on Saturday night, President Joe Biden was out in Washington on a Valentine’s week date-night, lingering over rigatoni with fennel sausage ragu before returning with his wife to the White House.

The next time he was seen in public was 36 hours later, striding out of St. Michael’s Cathedral in Kyiv into a bright winter day, air raid sirens wailing a reminder of both the risks and reason for visiting Ukraine as it nears a second year of war.

Cloaked in secrecy and weighted with history, Biden’s trip was the work of months of planning by only a small handful of his senior-most aides, who recognized long ago the symbolic importance of visiting the Ukrainian capital a year after Russia tried to capture it.

“One year later, Kyiv stands,” Biden declared Monday. “And Ukraine stands. Democracy stands.”

Yet it was more than symbolism that drove Biden to endure the significant risk of visiting an active war zone without significant US military assets on the ground.

In conversations behind closed doors at the Mariinsky Palace on Monday, Biden sought to engage President Volodymyr Zelensky in a detailed and urgent discussion about the next phase of the war, which US officials describe as having arrived at a critical juncture.

How the war advances in the coming months will depend in large part on the continued support of the United States, which Biden pledged Monday would be unceasing. If his message was meant as a reassuring one for Ukrainians, it was also intended as a reminder to Americans that the stakes of the conflict extend well beyond Ukraine’s borders.

A secret until the last minute

“This is so much larger than just Ukraine. It’s about freedom of democracy in Europe, it’s about freedom and democracy at large,” he said, his blue-and-yellow tie an overt nod to his Ukrainian hosts.

Keeping Biden’s plans secret required extraordinary measures on the part of the White House. In the weeks leading up to Biden’s travel, he and top aides repeatedly shot down the possibility of a trip to Ukraine. Every effort was made to maintain that position in the hour leading up to Biden’s surprise arrival in Kyiv.

That was in part due to the fluid nature of the trip itself. Even as the small circle of White House officials looped in on the planning grew confident it was an achievable undertaking, the realities of sending a president into a war zone where the US had no control over the air space were daunting.

The final decision was made in an Oval Office meeting on Friday evening, when Biden gave the final green light. Once the trip was on, US officials took steps to notify Moscow of their plans, an attempt at “deconfliction” meant to avoid unthinkable disaster while Biden was on the ground.

In Washington, however, the secrecy had to be maintained to actually pull it all off.

No notice was given to reporters on Sunday that Biden was no longer in Washington. The official White House schedule, released Sunday evening, still listed his departure for Poland at 7 p.m. ET on Monday.

His top national security spokesman denied there was a possibility the president would visit Ukraine in an interview that aired Sunday morning.

“We’re going to continue to use our convening power, to marshal the world, to galvanize support for Ukraine, but there are no plans for the president to enter Ukraine on this trip,” NSC spokesman John Kirby said in an interview on MSNBC’s “The Sunday Show with Jonathan Capehart.”

But at that point, Biden had already lifted off from Joint Base Andrews hours before, not in the usual plane that is synonymous with Air Force One, but instead in a smaller Air Force C-32.

Aboard was only a small clutch of senior advisers, one reporter and one photographer – whose electronic devices were taken from them before departure.

A 10-hour train ride through Ukraine

There would be a stop to refuel at a US base in Germany before continuing the flight into Poland. As he jetted eastward, Biden’s focus was plotting out his conversations with Zelensky, hoping to use his limited time wisely in discussing the coming months of fighting.

Biden landed in Rzeszow, the Polish town where he’d stopped in March of last year to visit US troops deployed near the Ukrainian border and humanitarian efforts supporting Ukrainian refugees. During that visit 11 months ago, he alluded to what became a long-running desire to extend his journey just a little further into Ukraine.

“I’m here in Poland to see firsthand the humanitarian crisis and quite frankly, part of my disappointment is that I can’t see it firsthand like I have in other places,” Biden said then. “They will not let me – understandably, I guess – cross the border and take a look at what’s going on in Ukraine.”

This time around, with an expanded set of US air assets overhead keeping close watch at the Polish border, he would make the trip. Biden, his small contingent of advisers and Secret Service that traveled with him boarded the train to Kyiv for the roughly 10-hour trip to the center of the war-torn country.

It was the culmination of a process that began months earlier, as Biden watched as a parade of his foreign counterparts each made the journey into Ukraine.

They first began visiting Kyiv in March 2022, when the prime ministers of Poland, Slovenia and the Czech Republic all arrived by train. Then-British Prime Minister Boris Johnson visited April 9, followed by visits from Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, French President Emmanuel Macron and then-Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin visited Kyiv on April 25 to meet Zelensky, at that point the top US officials to visit. Even first lady Dr. Jill Biden paid a surprise visit on Mother’s Day last year to a small city in the far southwestern corner of Ukraine. She met with Ukrainian first lady Olena Zelenska.

A risk Biden ‘wanted to take’

In the planning stages for this trip, Biden was presented with a range of options for a visit to Ukraine but decided that only the capital Kyiv made sense as a venue, a person familiar with the matter said.

The President never seriously considered any other locations – if he was going to go to Ukraine, he wanted to go to Kyiv.

As Biden was briefed over several months on the planning for a potential visit, the person said that Biden only once expressed concern about the risk of a visit to Ukraine – but that was about the extent to which his visit could endanger others, rather than about his own safety. Other officials were extremely concerned about Biden’s own safety and prepared a series of security contingency plans for the trip.

“This was a risk that Joe Biden wanted to take,” said White House communications director Kate Bedingfield. “It’s important to him to show up, even when it’s hard, and he directed his team to make it happen, no matter how challenging the logistics.”

On Monday, after the trip concluded, national security adviser Jake Sullivan declined to say whether Biden had to overrule Secret Service or military officials in order to proceed with the trip.

“He got a full presentation of a very good and very effective operational security plan. He heard that presentation, he was satisfied that the risk was manageable and he ultimately made a determination (to go),” Sullivan said.

CNN’s Jeremy Diamond contributed to this report.

. . .

“Biden visits Zelensky in Kyiv and says Putin ‘dead wrong’ on Ukraine war”

By James Waterhouse, Alice Cuddy and Kathryn Armstrong in Kyiv & London, 20 Feb 2023, BBC News

The US will back Ukraine in its fight against Russia for “as long as it takes”, US President Joe Biden has said on an unannounced visit to Kyiv.

“We have every confidence you’re going to continue to prevail,” he said.

Mr Biden’s first trip to Ukraine as president came days before the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion.

He said that Russia’s President Vladimir Putin had been “dead wrong” to think Russia could outlast Ukraine and its Western allies.

He met Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and the pair visited a memorial to soldiers who have died in the nine years since Russia annexed Crimea and its proxy forces captured parts of the eastern Donbas region.

Mr Biden’s presence was intended to reaffirm America’s “unwavering commitment to Ukraine’s democracy, sovereignty, and territorial integrity”, according to a White House statement.

He had taken a 10-hour train journey from Poland to reach Kyiv in secret, later returning to Poland. Russia was informed about the trip a few hours before President Biden’s departure for “deconfliction purposes”, a US official said.

After the visit, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced a new package of security assistance for Ukraine valued at $450m (£373m), including ammunition for howitzers and the Himars rocket system, Javelin missiles and air surveillance radars.

The US will also provide Kyiv with an extra $10m in emergency assistance to maintain Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, Mr Blinken said.

A new wave of sanctions against individuals and companies “that are trying to evade or backfill Russia’s war machine” will also be announced later this week.

Mr Zelensky said Ukraine’s victory over Russia depended on resolve and that he saw such determination in Mr Biden.

“It is now and in Ukraine that the fate of the world order, which is based on rules, on humanity… is being decided,” he said.

He also said that the two leaders had discussed the possibility of sending other weapons. Mr Zelensky has repeatedly called for F-16 fighter jets, something the US and other allies have so far stopped short of approving.

Commenting on the trip, Russian foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova said failure would befall those who, as she put it, “sold their souls to the Americans”.

In a scene that added drama to the most high-profile visit to Ukraine since the war began, air raid sirens wailed while President Biden and Mr Zelensky were in St Michael’s Cathedral in central Kyiv. The sirens sound regularly in the city.

While other world leaders have visited Ukraine over the past year, the US president’s appearance in Kyiv during a war in which American soldiers are not fighting is a show of unity at a time when Russia says Western support for Ukraine is waning.

The visit was welcomed by Ukrainians in Kyiv.

“I’m so grateful for his support – it means so much to us,” Roksoliana Gera told the BBC. “I appreciate his courage, that he took on this challenge and came to show the support of the American nation.”

Oleksandra Soloviova said the visit showed Russia that “the US supports us and will continue supporting us, with sanctions and military equipment”.

The Ukrainian president’s chief of staff, Andriy Yermak, said the visit had been strategic as well as historic. “Many issues are being solved and those that have stalled will be accelerated,” he said.

The US is one of Ukraine’s biggest allies and the state department has so far announced $24.9bn in military assistance.

In January, Mr Biden announced that the US would send 31 battle tanks and longer-range missiles are also on their way.

However, there is a growing political divide in the US over the amount of aid Kyiv should receive in future.

President Biden’s visit to Kyiv came ahead of a three-day visit to Poland where he will meet the country’s President, Andrzej Duda, and east European members of the Nato military alliance.

In another development, China’s foreign minister has said Beijing is deeply worried by the escalation of the war in Ukraine and the danger it could spiral out of control.

“We will continue to urge peace and promote talks and provide Chinese wisdom for a political solution to the crisis in Ukraine,” Qin Gang told a forum in Beijing.

“Together with the international community, we will jointly promote dialogue, negotiate and address the concerns of all parties and seek common security. In the meantime, we urge certain countries to immediately stop fuelling the fire, stop shifting the blame to China and stop hyping up Ukraine today, Taiwan tomorrow.”

Earlier, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken suggested China was considering supplying weapons and ammunition to Russia for the war – a claim strongly denied by the Chinese.