Issue of the Week: Human Rights, Personal Growth

The Long Read in The Guardian in London, Solidarity and strategy: the forgotten lessons of truly effective protest, is a critical historical review and reminder of what an organized ongoing protest movement requires to succeed, versus a protest by itself, no matter how large or popular.

We don’t agree with every characterization in the article, but in the main, we agree wholeheartedly. And agreeing isn’t really the point. The facts are the point,

The article begins:

Nothing appears more surprising to those, who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit submission, with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers,” the Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote in his 1777 essay Of the First Principles of Government. Centuries later, his observation still holds. Despite having numbers on our side, the vast majority of people continue to be dominated by a small subset of the population. Why?

Today, an oligarchic minority rules because they have extreme wealth. The 2022 World Inequality Report found that the richest 10% today take over 52% of all income, leaving the poorest half just 8.5%. The same year, the bottom half of US citizens, or more than 160 million people, held a mere 2% of the country’s total wealth. An upper class owns most of the land and capital, which allows them, in turn, to exert control over politics and pass on enormous fortunes to their offspring, effectively establishing a modern-day aristocracy.

In opposition to the power of money stands the power of the many – at least in theory. In practice, things are more complicated. As Hume noted long ago, power does not flow from sheer numbers alone. What matters is not merely absolute numbers but organised numbers. Without solidarity and organisation, numerical advantage doesn’t mean much. It doesn’t matter if there are thousands of workers and only a handful of bosses if those workers lack a union, or if there are millions of citizens and one dictator if people are too atomised and afraid to try to topple the regime.

However, there is much better news in lengthy examples in the piece of historic accomplishments. And a blue print for one of the critical avenues to changing the world.

Here it is:

Solidarity and strategy: the forgotten lessons of truly effective protest, by Astra Taylor and Leah Hunt-Hendrix, The Guardian, The Long Read, March 2024

Organising is a kind of alchemy: it turns alienation into connection, despair into dedication, and oppression into strength

‘Nothing appears more surprising to those, who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit submission, with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers,” the Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote in his 1777 essay Of the First Principles of Government. Centuries later, his observation still holds. Despite having numbers on our side, the vast majority of people continue to be dominated by a small subset of the population. Why?

Today, an oligarchic minority rules because they have extreme wealth. The 2022 World Inequality Report found that the richest 10% today take over 52% of all income, leaving the poorest half just 8.5%. The same year, the bottom half of US citizens, or more than 160 million people, held a mere 2% of the country’s total wealth. An upper class owns most of the land and capital, which allows them, in turn, to exert control over politics and pass on enormous fortunes to their offspring, effectively establishing a modern-day aristocracy.

In opposition to the power of money stands the power of the many – at least in theory. In practice, things are more complicated. As Hume noted long ago, power does not flow from sheer numbers alone. What matters is not merely absolute numbers but organised numbers. Without solidarity and organisation, numerical advantage doesn’t mean much. It doesn’t matter if there are thousands of workers and only a handful of bosses if those workers lack a union, or if there are millions of citizens and one dictator if people are too atomised and afraid to try to topple the regime.

Yet history has shown time and again that even a proportionally small number of people, if they are well organised, can have an outsized effect. People getting organised is what brought down slavery and Jim Crow, outlawed child labour in the US and elsewhere, and overthrew the legal subjugation of women. If it wasn’t for people acting in concert, universal suffrage would not exist, and neither would the eight-hour workday or the weekend. There would be no entitlement to basic wages, unemployment insurance, or social services, including public education. It would still be a crime to be gay or trans. Women would still be under the thumb of their husbands and at the mercy of sexist employers, and abortion would never have been legalised, however tenuously. Disabled people would lack basic civil rights. The environment would be totally unprotected and even more polluted. Without collective action, colonised people would never have ousted their oppressors, Indigenous people would not have survived attacks from genocidal settlers, and apartheid would not have been overthrown.

Often, the powerful like to take credit for social change after the fact, portraying progress as the inevitable result of economic development and enlightened, beneficent leadership. We praise President Franklin Delano Roosevelt for forging the New Deal, with its wealth of social programmes and labour protections, instead of paying tribute to the militant labour movement that forced his administration’s hand, inflicting real costs on bosses and investors through thousands of work stoppages, picket lines and strikes. Similarly, the civil rights legislation of the 1960s did not come about because of Lyndon B Johnson’s bravery, but rather because a militant and well-organised minority fought boldly against a hostile and often violent majority, pushing them to shift their behaviours, if not their beliefs.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the labour movement and the civil rights movement had a complex relationship, but ultimately collaboration strengthened them both. The 1963 March on Washington was a march for “jobs and freedom”, and many of the signs held aloft during that historic gathering bore the stamp of the trade unions that helped fund the event and provided critical logistical support. In the decades that followed, there was a steep decline in the membership bases of unions and civic associations, as the right wing began a concerted campaign to undermine their legal ability to organise.

Scholars have since documented the way the late 20th century was, for the activist left, characterised by a shift to a shallow, professional and often philanthropically funded model of “advocacy”, one that elevates self-appointed leaders and elite experts to speak on behalf of constituencies to whom they are not directly accountable. Rather than organising people to fight for themselves, these groups promote professionals who attempt to exert influence inside the halls of power. Instead of protests, they publish white papers; in place of strikes, they circulate statements; instead of cultivating solidarity, they seek access to decision-makers.

These kinds of elite strategies can occasionally produce positive results, but the approach is often counterproductive, and certainly not democratic. This top-down approach puts its faith in the persuasive abilities of a tiny few, and denies the fact that politics is a power struggle – and that engaging and organising more people gives your position more leverage.

The sociologist Theda Skocpol uses the phrase “diminished democracy” to describe this shift from membership to management-led initiatives. A similar trend of diminishing democracy is apparent in the growing number of people who think of themselves as allies or activists, but who are not connected to political organisations. Millions of concerned citizens support social justice causes – they want an end to racism, a shift toward ecological sustainability, better treatment for workers, and so on – and they raise awareness by sharing on social media, committing random acts of kindness, voting for progressive candidates and showing up at rallies. And yet, they are not actually organised.

The diminished organisational capacity in American civic life is reflected in the weakness of social movements that appear, on the surface, to be robust. The 21st century has witnessed the biggest protests, and the most popular petitions, in history, yet they have produced comparatively small effects. On 15 February 2003, across the world, an estimated 10 million people came out in opposition to the impending war in Iraq. Since then, in the US, protests have only become bigger. In 2017, the Women’s March, held the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration, attracted an estimated 5 million people, taking part in at least 400 actions worldwide, from large cities to small towns. In the autumn of 2019, teenagers called for a global climate strike, which inspired more than 6 million people to protest at 4,500 locations in 150 countries. In 2020, the protests against racism and police brutality continued the trend, rapidly becoming the largest movement in the country’s history. After the murder of George Floyd, an estimated 15 to 26 million people demonstrated nationwideover a one-month period.

Of course, there is much to cheer about here, especially when people move from the sidelines to the streets. During the anti-police brutality protests of 2020, half of those who protested reported that it was their first time ever doing so.

But we’ve seen again and again that size alone doesn’t guarantee success. President George W Bush dismissed the anti-war actions as a “focus group”, and barrelled ahead with an illegal war that would cost more than 1 million lives; protesters never unleashed the kind of sustained resistance that played a role in ending the war in Vietnam. The Women’s March protests were meaningful and inspiring to the participants, and offered a vital outlet for dissent that fed the electoral energy that deposed Donald Trump, but failed to deeply shift policy or the patriarchal status quo. The youth leaders of the global climate strike hoped for something more confrontational – teenage organiser implored adult allies to walk off the job and escalate the fight – but the few grownups who skipped work didn’t do so in a coordinated fashion. If the adults had organised as the teenagers did and halted business as usual around the world, more might have come of it. The racial justice protests of 2020 were historic and changed the terms of the national debate, and many local groups and electoral campaigns harnessed the movement’s momentum to important effect – but the scale of these victories hardly matches the massive outcry and depth of public support the numbers in the streets indicate. What might have happened had a larger fraction of the tens of millions who demonstrated been channelled into member-based organisations to work toward common goals?

Elsewhere in the world we see a similar problem. The protests of the Arab spring brought out huge numbers of people across the Middle East, from Tunisia and Egypt to Bahrain and Syria. The numbers sparked significant political consequences in some cases, but the lack of organisation around clear alternatives meant that the results were not necessarily improvements. Syria devolved into a devastating and protracted civil war; Egypt saw its authoritarian leader resign, only to eventually be replaced by a military dictatorship; Tunisia was the lone nation in the region that adopted democracy, but a decade after the 2011 protests, its president was already reconsolidating power, expanding his executive powers, and diminishing checks and balances, undermining the reforms that the revolution initiated.

Uprisings can sometimes create a mirage of popular power, but without the organisation, strategy and vision necessary to influence what follows, the presence of large numbers is insufficient to produce transformative results, leaving more disciplined and mercenary formations to fill the void.

It’s worth lingering on this dilemma, because it is tempting to think that the problem is that our movements aren’t big enough. This is where the question of organisation comes in. It’s not enough to pursue numbers alone. If material transformation is your goal, it may well be better to have a dozen staunch supporters than 1,000 fair-weather friends; 100 dedicated organisers will probably accomplish more than 100,000 email contacts or retweets.

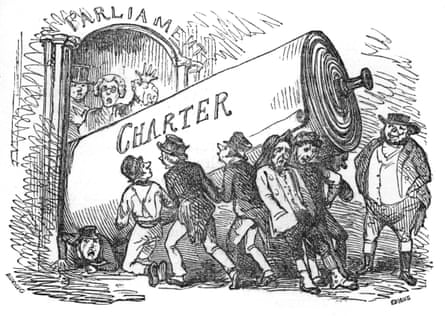

Consider what it took to compose and deliver a petition two centuries ago. In 1839, the London Working Men’s Association presented a People’s Charter to the British parliament, demanding electoral reforms including universal male suffrage and annual elections. They gathered more than 1,280,000 names, representing workers of every imaginable occupation and background, on a massive scroll that was three miles long. Simply transporting it across town was a feat that demonstrated the dedication and ingenuity of the ringleaders, and the depth of popular support. When the petition was rejected by parliament, public outcry inspired organisers to try again. They presented a second charter in May 1842, signed by more than 3 million people, which was also ignored, and then a third petition delivered in 1848. Today, the UK parliament’s official website recounts this history, noting that while the Chartist movement formally disbanded before it succeeded, it helped catalyse change, including the electoral reform bills of 1867 and 1884, and that by 1918 “five of the Chartists’ six demands had been achieved”. Today, a million virtual petition signatures are an indication of good digital marketing skills, not the devotion of the organisers or the signatories to a cause.

This is why labour unions are so critically important. They organise people to come together in the real world and to engage in a series of collective actions that ultimately can’t be ignored. At their best, unions facilitate collective discipline and long-haul dedication, enabling people to use a clear form of leverage: the withholding of labour.

To make a real and lasting mark, transformative solidarity must involve expanding the number of supporters while also strengthening the relationships between participants. Consider the civil rights movement. Today, everyone knows about the Montgomery bus boycott led by Rosa Parks, but few realise it lasted 381 days, and we rarely acknowledge the years of organising that laid the groundwork, nor do we recall earlier efforts that helped hone the boycott in Montgomery, including the Baton Rouge bus boycott of 1953. Similarly, we have vague inklings that the suffragettes struggled to secure the right to vote, but we often fail to grasp the tireless decades of meetings, planning and petitioning, or we forget the fact that their tactics included property destruction: bombing, arson and breaking windows. These organisers didn’t confine themselves to civil debate, or seek unity with racist and patriarchal authorities who viewed Black people and women as subhuman. They engaged in an unremitting, high-stakes confrontation.

An excellent example of the power of radical imagination in building transformative solidarity is the movement for disability justice. The idea that disabled people occupy a distinct social category first began to take shape amid the large-scale social changes of the 19th-century industrial era. This was the period when workers began to see themselves as a cohesive group with a unique form of social power, and when women and also gay people, particularly gay men, began to understand themselves in new ways.

Something similar was true of disabled people. Of course, mentally and physically impaired people have always existed, but the nature of the barriers and prejudice disabled people face, as well as the ways disability is understood, have changed as underlying conditions have evolved. While religious superstition and persecution of disabled people were common during the middle ages, preindustrial economies also permitted many people with a disability to contribute to their household’s economic survival; they lived and worked alongside family members at home or in nearby farms and workshops, doing tasks that their bodies could accomplish. As production industrialised, this ceased to be the case. Piecework and factory lines demanded rote precision, and people’s bodies were increasingly valued for their ability to make precise mechanical movements. “Industrial capitalism thus created not only a class of proletarians but also a new class of ‘disabled’ who did not conform to the standard worker’s body and whose labour-power was effectively erased, excluded from paid work,” observe scholars Marta Russell and Ravi Malhotra. “As a result, disabled persons came to be regarded as a social problem and a justification emerged for segregating them out of mainstream life and into a variety of institutions, including workhouses, asylums, prisons, colonies and special schools.”

In a world of rapidly increasing inequality and cutthroat competition, disability came to signify dependence and inferiority as eugenicist ideas gained ground. Social Darwinism, a popular form of eugenics thinking in the 19th century, rationalised discrimination against people with physical and mental impairments as well as other marginalised populations, to whom disabilities were attributed. Women, Black people, Jewish people, gay people and immigrants were all said to lack the physical and mental capacities required for full equality and inclusion – they were emotional, feeble-minded, degenerate, diseased and so on. Sadly, members of these groups too often reinforced the ableist stigma, distancing themselves from disabled people in an attempt to assert their full humanity and prove their relative worth.

Given these pervasive prejudices and other barriers, it’s no wonder solidarity was slow to build among (and with) disabled people. And yet, if there is any oppressed group that has numbers on its side, it ispeople with disabilities, who make up the world’s largest minority – and a growing one, given the fact that every able-bodied person lucky to live long enough faces the prospect of joining those ranks. (One might imagine that would be grounds for a robust alliance of the able-bodied and disabled, yet the typical attitude of the able-bodied toward disabled people remains pity, not solidarity.)

In the 1970s, the disability justice movement took off in earnest when people began to apply insights from the movement for racial equality to their own lives: perhaps they too were part of a constituency that was also entitled to civil rights? The mere possibility of a world that embraced every individual, regardless of physical or mental ability or health, provided motivation.

Part of the challenge, in those early days, was that many disabled people didn’t necessarily identify as such. Instead, they saw themselves as individuals with distinctive embodiments or medical conditions. It wasn’t obvious to people with different impairments that they were part of the same “Us”. For solidarity to develop between a deaf person, a blind person, a person with cerebral palsy, a person with polio, a person missing a limb, a person with Down’s syndrome, and a person with autism or another form of neurodivergence, a shift in consciousness was required, an act of radical imagination.

In the early days of the disability rights movement, organising work was even more challenging than it is today. Countless obstacles blocked the way, many of them physical, such as the existence of stairs where there could be a ramp. Even when disabled individuals embraced solidarity in principle, they had a difficult time physically joining with others to put their values into practice. When the call for disability rights first rang out, dropped kerbs and wheelchair lifts on public buses were rare or nonexistent in the US, and channels of communications were similarly inaccessible, which meant getting the word out could be as hard as getting out into the streets. Fortunately, activists understood that a small number of participants could have an outsised impact if they used the right tactics and had the right strategy. And so they began coordinated and confrontational campaigns of civil disobedience to vividly dramatise their oppression and demand public services and equal protection under the law.

In 1977 in San Francisco, about 150 disabled radicals occupied the fourth floor of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare for 25 days. “Blind people, deaf people, wheelchair users, disabled veterans, people with developmental and psychiatric disabilities and many others, all came together,” leader Judith Heumann later recalled. “We overcame years of parochialism.”

The demonstrators held their ground despite great physical discomfort – the space was not meant to be lived in, and certainly not by people with a wide range of functional needs – and demanded that officials clarify and enforce existing rules protecting disabled people from discrimination under certain circumstances. Knowledgable disabled spokespeople sparred with lawmakers about legislative proposals in televised broadcasts, and the organisers sent a delegation to Washington to further lobby officials. Brad Lomax, a member of the Black Panther Party who had multiple sclerosis, was responsible for the party bringing hot meals to the sit-in each day. The pivotal protest helped strengthen government regulations and provided an example for organisers around the country to follow. In Denver the next year, 19 disabled activists, the Gang of 19, got out of their wheelchairs and lay down to stop traffic, demanding accessible public transportation. That event directly led to the creation of the Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit, Adapt, which organised similar protests across the country and brought a further degree of militancy and national visibility to the movement.

Once disabled people began to organise to build transformative solidarity, they changed the landscape of the US at an astonishing pace. In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed, a groundbreaking piece of legislation that, in many ways, is more far-reaching than its civil rights-era predecessor, for it requires not only that establishments open their doors to previously excluded groups, but that they remake the entrance, widening the frame and adding a ramp or an elevator.

Today, we take dropped kerbs, wheelchair lifts, accessible bathroom stalls and closed captioning for granted, but each of these adaptations was hard-won. During the lead-up to the ADA’s passage, disabled activists secured critical support from key Republican officials, finding common ground with individual politicians who had disabled loved ones whose rights they felt called to protect. At the same time, activists refused to play into attempts to divide and conquer by homophobic conservative politicians who wanted the legislation to deny protections for people with HIV and Aids. Society has been dramatically transformed as a result of strategic organising by disabled people who imagined a world where discrimination wasn’t sanctioned by the state, and where people with a wide range of embodiments would be able to move around not only unimpeded, but actively and creatively assisted.

Where disability rights are concerned, incredible progress has been made, but much remains to be done. Today, resources are funnelled into youth- and life-extension therapies, instead of into planning for the unavoidable reality of human difference, ageing and fragility. We obsess over personal wellness while sidelining the issue of public health. We focus on cures for impairments and illness, when we should also work to make the world more hospitable to those who are disabled or unwell. Meanwhile, we fail to examine how our economic system maims and sickens millions – think repetitive stress injuries on the job, how poverty negatively impacts mental health, or asthma or cancer caused by poisoned air – while denying people treatment and care.

Instead of submitting to this injury and devaluation, we should heed disability theorist Alison Kafer’s call to organise toward what she calls an “accessible future” – one that values and makes space for a multitude of bodies and modes of moving, thinking and being. As some early theorists of solidarity recognised more than a century ago, we are all interdependent, and we all begin and often end our lives in states of total dependency. Instead of marginalising disabled people and vilifying vulnerability, a society founded on the principle of solidarity would understand human variation and mutual reliance as the basis of a decent and desirable society.

The kind of solidarity required to secure a more accessible and inclusive future will not appear spontaneously. It needs to be organised into being. Real organising is a kind of alchemy: a process that turns alienation into connection, despair into dedication, and oppression into strength while fashioning a whole that is stronger than its parts.

Again and again, people build solidarity and leave the world a better place, as the examples of movements for labour, civil and disability rights all show. And yet we still struggle to tell these inherently collective stories. Too often the tale of “Us” gets whittled down into a tale of an “I” – a story about a visionary liberator or self-sacrificing saint who changed the world. We turn a handful of protesters and rebels into icons, but hear comparatively little about the organising communities that shaped and supported them, or the ones that they tried to build to carry their efforts forward.

Our simplifying, celebrity-obsessed culture distorts the legacies of talented organisers and historical figures while also amplifying a handful of contemporary telegenic activists – the latter too often possessing a knack for social media and self-promotion, but lacking a commitment to an organised base they are accountable to. This emphasis on lone heroes is a kind of flipside to the fixation on increasing numbers for their own sake, or on notching bigger protests rather than better ones. An unhelpful binary emerges as a result: social movements are imagined to consist of charismatic individuals on the one side and nameless masses on the other.

But real organising is something else entirely. Every successful effort to challenge the status quo has required a multitude of people playing a wide range of roles. Allowing for this diversity is one way to grow both numbers and meaningful organisation. When we come together in an organised fashion – forging new self-conceptions, embracing radical visions and acting strategically – we can wield the power of numbers to disrupt business as usual, wrest concessions and pave the way for future victories.

Adapted from Solidarity: The Past, Present, and Future of a World-Changing Idea, published by Pantheon Books

Follow the Long Read on X at @gdnlongread, listen to our podcasts hereand sign up to the long read weekly email here.

- “Brooks and Capehart on Trump’s decision to launch strikes on Iran”, PBS NewsHour

- Issue of the Week: War

- “The Original”, The New Yorker

- “Big Change Seems Certain in Iran. What Kind Is the Question”, The New York Times

- “Trump Says War Could Last Weeks and Offers Contradictory Visions of New Regime”, The New York Times

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017