Issue of the Week: Human Rights, Personal Growth

On June 17, 1994, if you were alive in the US and of mid-grammar school age and above, you likely remember exactly where you were and what you were doing. With 100 million Americans (and many others worldwide) you were watching, non-stop, for hours, OJ Simpson driving with a friend on the LA freeways in a white Bronco threatening to kill himself as the LAPD was in pursuit.

Nothing like this had ever happened before in media or in the culture, on many levels. And the trial that followed of Simpson accused of murdering his former wife and her friend, was a two year non-stop reality TV event that had no precedent. Every day, it was all OJ, all the time.

It’s affected everything in the culture and media ever since.

All of this has hit the nation and the world again, with much reflection, because OJ Simpson died today.

The ongoing impact of what happened 30 years ago will receive more attention from us to come. The points to be made have been made relentlessly by us already. But the impact of this event deserves more focus.

Not the least reason being the extraordinary convergence of multi-dimensional issues involved which are about so many of the most critical issues facing our society. We put the issue under Human Rights for multiple obvious (hopefully) reasons. But we also put it under Personal Growth because it marked a downward plunge from the opposite of growth to multiple levels of regression (as well as highlighting personal and social ills that had alreasdy been there for a long time) in the culture at large.

Before proceeding, we need to mention the ESPN documentary, “OJ: Made in America”, which is linked in the articles below.

It is a several part series that is one of the finest documentaries ever made. It’s not just riveting, it’s consuming, even if you knew nothing about the subject, especially if you knew nothing. It was made by Ezra Edelman, the son of Marian Wright Edelman, the inspiring child activist for decades and Peter Edelman, Bobby Kennedy’s aide. As one of our Issues of the Week in February 2016 noted, Peter “went on, among other things, to become president of the eminent National Center for Youth Law, which joined …[two of us at Planet Earth Foundation at the time] as an amicus curiae in a personal case on behalf of the best interest of sexually abused children that reached the Washington State Supreme Court and was won unanimously on all counts with the decision written by the Chief Justice–a precedent to this day.” We were judges in the Independent Spirit Awards that year and voted for “OJ: Made in America” as best documentary, which it won, as it did at the Academy Awards the next day.

As we said at the time: “Don’t miss it. A journey through America on race and everything else from the 60’s until now in so many ways never revealed so well.”

We start with the basics, the front page obituary and deeply perceptive articles posted tonight and dated tomorrow in The New York Times and CNN:

“O.J. Simpson, Football Star Whose Trial Riveted the Nation, Dies at 76”

By Robert D. McFadden, Front Page, April 11, 2024

He ran to football fame and made fortunes in movies. His trial for the murder of his former wife and her friend became an inflection point on race in America.

O.J. Simpson, who ran to fame on the football field, made fortunes as an all-American in movies, television and advertising, and was acquitted of killing his former wife and her friend in a 1995 trial in Los Angeles that mesmerized the nation, died on Wednesday at his home in Las Vegas. He was 76.

The cause was cancer, his family announced on social media.

The jury in the murder trial cleared him, but the case, which had held up a cracked mirror to Black and white America, changed the trajectory of his life. In 1997, a civil suit by the victims’ families found him liable for the deaths of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald L. Goldman, and ordered him to pay $33.5 million in damages. He paid little of the debt, moved to Florida and struggled to remake his life, raise his children and stay out of trouble.

In 2006, he sold a book manuscript, titled “If I Did It,” and a prospective TV interview, giving a “hypothetical” account of murders he had always denied committing. A public outcry ended both projects, but Mr. Goldman’s family secured the book rights, added material imputing guilt to Mr. Simpson and had it published.

In 2007, he was arrested after he and other men invaded a Las Vegas hotel room of some sports memorabilia dealers and took a trove of collectibles. He claimed that the items had been stolen from him, but a jury in 2008 found him guilty of 12 charges, including armed robbery and kidnapping, after a trial that drew only a smattering of reporters and spectators. He was sentenced to nine to 33 years in a Nevada state prison. He served the minimum term and was released in 2017.

Over the years, the story of O.J. Simpson generated a tide of tell-all books, movies, studies and debate over questions of justice, race relations and celebrity in a nation that adores its heroes, especially those cast in rags-to-riches stereotypes, but that has never been comfortable with its deeper contradictions.

There were many in the Simpson saga. Yellowing old newspaper clippings yield the earliest portraits of a postwar child of poverty afflicted with rickets and forced to wear steel braces on his spindly legs, of a hardscrabble life in a bleak housing project and of hanging with teenage gangs in the tough back streets of San Francisco, where he learned to run.

“Running, man, that’s what I do,” he said in 1975, when he was one of America’s best-known and highest-paid football players, the Buffalo Bills’ electrifying, swivel-hipped ball carrier, known universally as the Juice. “All my life I’ve been a runner.”

And so he had — running to daylight on the gridiron of the University of Southern California and in the roaring stadiums of the National Football League for 11 years; running for Hollywood movie moguls, for Madison Avenue image-makers and for television networks; running to pinnacles of success in sports and entertainment.

Along the way, he broke college and professional records, won the Heisman Trophy and was enshrined in pro football’s Hall of Fame. He appeared in dozens of movies and memorable commercials for Hertz and other clients; was a sports analyst for ABC and NBC; acquired homes, cars and a radiant family; and became an American idol — a handsome warrior with the gentle eyes and soft voice of a nice guy. And he played golf.

It was the good life, on the surface. But there was a deeper, more troubled reality — about an infant daughter drowning in the family pool and a divorce from his high school sweetheart; about his stormy marriage to a stunning young waitress and her frequent calls to the police when he beat her; about the jealous rages of a frustrated man.

Calls to the Police

The abuse left Nicole Simpson bruised and terrified on scores of occasions, but the police rarely took substantive action. After one call to the police on New Year’s Day, 1989, officers found her badly beaten and half-naked, hiding in the bushes outside their home. “He’s going to kill me!” she sobbed. Mr. Simpson was arrested and convicted of spousal abuse, but was let off with a fine and probation.

The couple divorced in 1992, but confrontations continued. On Oct. 25, 1993, Ms. Simpson called the police again. “He’s back,” she told a 911 operator, and officers once more intervened.

Then it happened. On June 12, 1994, Ms. Simpson, 35, and Mr. Goldman, 25, were attacked outside her condominium in the Brentwood section of Los Angeles, not far from Mr. Simpson’s estate. She was nearly decapitated, and Mr. Goldman was slashed to death.

The Complex Life of O.J. Simpson

- Acting Fame: Before O.J. Simpson became synonymous with the sensational murder trial that riveted the nation in the mid-1990s, he was a football star turned Hollywood fixture who played roles as varied as an astronaut, a comic detective and a fake priest.

- A Turbulent Era: From the car chase to the verdict, the murder case became an inextricable part of Los Angeles history in the 1990s, and Angelenos to this day still ponder what happened.

- Living With the Aftershocks: Simpson tried to shed his Blackness, a writer muses, but his all-consuming murder trial put the historically lurid American psyche on full display.

- The Kardashian Connection: Long before the Kardashians became a star attraction on reality television, the family name first came to prominence when Simpson was on trial.

The knife was never found, but the police discovered a bloody glove at the scene and abundant hair, blood and fiber clues. Aware of Mr. Simpson’s earlier abuse and her calls for help, investigators believed from the start that Mr. Simpson, 46, was the killer. They found blood on his car and, in his home, a bloody glove that matched the one picked up near the bodies. There was never any other suspect.

Five days later, after Mr. Simpson had attended Nicole’s funeral with their two children, he was charged with the murders, but fled in his white Ford Bronco. With his old friend and teammate Al Cowlings at the wheel and the fugitive in the back holding a gun to his head and threatening suicide, the Bronco led a fleet of patrol cars and news helicopters on a slow 60-mile televised chase over the Southern California freeways.

Networks pre-empted prime-time programming for the spectacle, some of it captured by news cameras in helicopters, and a nationwide audience of 95 million people watched for hours. Overpasses and roadsides were crowded with spectators. The police closed highways and motorists pulled over to watch, some waving and cheering at the passing Bronco, which was not stopped. Mr. Simpson finally returned home and was taken into custody.

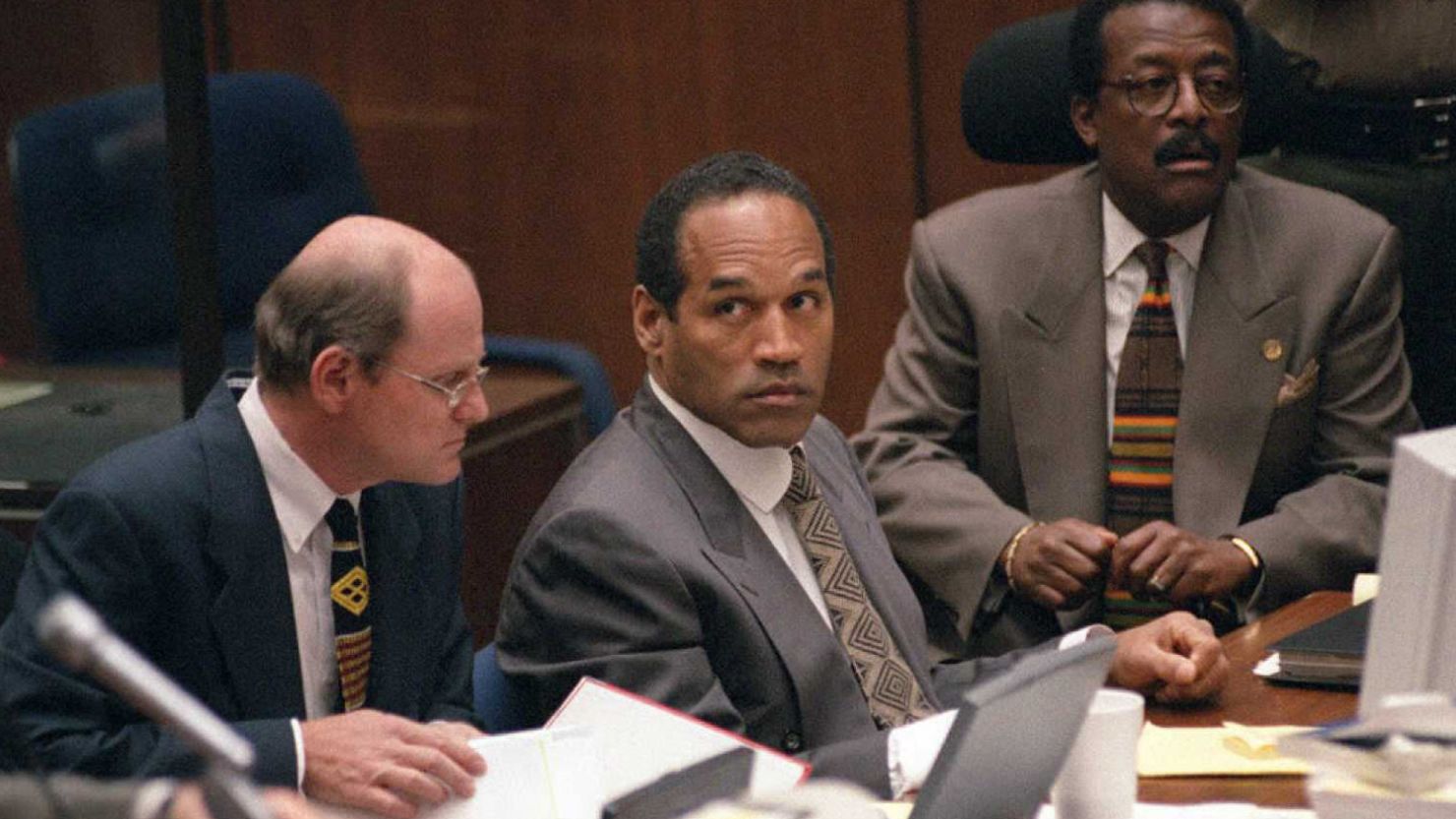

The ensuing trial lasted nine months, from January to early October 1995, and captivated the nation with its lurid accounts of the murders and the tactics and strategy of prosecutors and of a defense that included the “dream team” of Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., F. Lee Bailey, Alan M. Dershowitz, Barry Scheck and Robert L. Shapiro.

The prosecution, led by Marcia Clark and Christopher A. Darden, had what seemed to be overwhelming evidence: tests showing that blood, shoe prints, hair strands, shirt fibers, carpet threads and other items found at the murder scene had come from Mr. Simpson or his home, and DNA tests showing that the bloody glove found at Mr. Simpson’s home matched the one left at the crime scene. Prosecutors also had a list of 62 incidents of abusive behavior by Mr. Simpson against his wife.

But as the trial unfolded before Judge Lance Ito and a 12-member jury that included 10 Black people, it became apparent that the police inquiry had been flawed. Photo evidence had been lost or mislabeled; DNA had been collected and stored improperly, raising a possibility that it was tainted. And Detective Mark Fuhrman, a key witness, admitted that he had entered the Simpson home and found the matching glove and other crucial evidence — all without a search warrant.

‘If the Glove Don’t Fit’

The defense argued, but never proved, that Mr. Fuhrman planted the second glove. More damaging, however, was its attack on his history of racist remarks. Mr. Fuhrman swore that he had not used racist language for a decade. But four witnesses and a taped radio interview played for the jury contradicted him and undermined his credibility. (After the trial, Mr. Fuhrman pleaded no contest to a perjury charge. He was the only person convicted in the case.)

In what was seen as the crucial blunder of the trial, the prosecution asked Mr. Simpson, who was not called to testify, to try on the gloves. He struggled to do so. They were apparently too small.

“If the glove don’t fit, you must acquit,” Mr. Cochran told the jury later.

In the end, it was the defense that had the overwhelming case, with many grounds for reasonable doubt, the standard for acquittal. But it wanted more. It portrayed the Los Angeles police as racist, charged that a Black man was being railroaded, and urged the jury to think beyond guilt or innocence and send a message to a racist society.

On the day of the verdict, autograph hounds, T-shirt vendors, street preachers and paparazzi engulfed the courthouse steps. After what some news media outlets had called “The Trial of the Century,” producing 126 witnesses, 1,105 items of evidence and 45,000 pages of transcripts, the jury — sequestered for 266 days, longer than any in California history — deliberated for only three hours.

Much of America came to a standstill. In homes, offices, airports and malls, people paused to watch. Even President Bill Clinton left the Oval Office to join his secretaries. In court, cries of “Yes!” and “Oh, no!” were echoed across the nation as the verdict left many Black people jubilant and many white people aghast.

In the aftermath, Mr. Simpson and the case became the grist for television specials, films and more than 30 books, many by participants who made millions. Mr. Simpson, with Lawrence Schiller, produced “I Want to Tell You,” a thin mosaic volume of letters, photographs and self-justifying commentary that sold hundreds of thousands of copies and earned Mr. Simpson more than $1 million.

He was released after 474 days in custody, but his ordeal was hardly over. Much of the case was resurrected for the civil suit by the Goldman and Brown families. A predominantly white jury with a looser standard of proof held Mr. Simpson culpable and awarded the families $33.5 million in damages. The civil case, which excluded racial issues as inflammatory and speculative, was a vindication of sorts for the families and a blow to Mr. Simpson, who insisted that he had no chance of ever paying the damages.

Mr. Simpson had spent large sums for his criminal defense. Records submitted in the murder trial showed his net worth at about $11 million, and people with knowledge of the case said he had only $3.5 million afterward. A 1999 auction of his Heisman Trophy and other memorabilia netted about $500,000, which went to the plaintiffs. But court records show he paid little of the balance that was owed.

He regained custody of the children he had with Ms. Simpson, and in 2000 he moved to Florida, bought a home south of Miami and settled into a quiet life, playing golf and living on pensions from the N.F.L., the Screen Actors Guild and other sources, about $400,000 a year. Florida laws protect a home and pension income from seizure to satisfy court judgments.

The glamour and lucrative contracts were gone, but Mr. Simpson sent his two children to prep school and college. He was seen in restaurants and malls, where he readily obliged requests for autographs. He was fined once for powerboat speeding in a manatee zone, and once for pirating cable television signals.

In 2006, as the debt to the murder victims’ families grew with interest to $38 million, he was sued by Fred Goldman, the father of Ronald Goldman, who contended that his book and television deal for “If I Did It” had advanced him $1 million and that it had been structured to cheat the family of the damages owed.

The projects were scrapped by News Corporation, parent of the publisher HarperCollins and the Fox Television Network, and a corporation spokesman said Mr. Simpson was not expected to repay an $800,000 advance. The Goldman family secured the book rights from a trustee after a bankruptcy court proceeding and had it published in 2007 under the title “If I Did It: Confessions of the Killer.” On the book’s cover, the “If” appeared in tiny type, and the “I Did It” in large red letters.

Another Trial, and Prison

After years in which it seemed he had been convicted in the court of public opinion, Mr. Simpson in 2008 again faced a jury. This time he was accused of raiding a Las Vegas hotel room in 2007 with five other men, most of them convicted criminals and two armed with guns, to steal a trove of sports memorabilia from a pair of collectible dealers.

Mr. Simpson claimed that he was only trying to retrieve items stolen from him, including eight footballs, two plaques and a photo of him with the F.B.I. director J. Edgar Hoover, and that he had not known about any guns. But four men, who had been arrested with him and pleaded guilty, testified against him, two saying they had carried guns at his request. Prosecutors also played hours of tapes secretly recorded by a co-conspirator detailing the planning and execution of the crime.

On Oct. 3 — 13 years to the day after his acquittal in Los Angeles — a jury of nine women and three men found him guilty of armed robbery, kidnapping, assault, conspiracy, coercion and other charges. After Mr. Simpson was sentenced to a minimum of nine years in prison, his lawyer vowed to appeal, noting that none of the jurors were Black and questioning whether they could be fair to Mr. Simpson after what had happened years earlier. But jurors said the double-murder case was never mentioned in deliberations.

In 2013, the Nevada Parole Board, citing his positive conduct in prison and participation in inmate programs, granted Mr. Simpson parole on several charges related to his robbery conviction. But the board left other verdicts in place. His bid for a new trial was rejected by a Nevada judge, and legal experts said that appeals were unlikely to succeed. He remained in custody until Oct. 1, 2017, when the parole board unanimously granted him parole when he became eligible.

Certain conditions of Mr. Simpson’s parole — travel restrictions, no contacts with co-defendants in the robbery case and no drinking to excess — remained until 2021, when they were lifted, making him a completely free man.

Questions about his guilt or innocence in the murders of his former wife and Mr. Goldman never went away. In May 2008, Mike Gilbert, a memorabilia dealer and former crony, said in a book that Mr. Simpson, high on marijuana, had admitted the killings to him after the trial. Mr. Gilbert quoted Mr. Simpson as saying that he had carried no knife but that he had used one that Ms. Simpson had in her hand when she opened the door. He also said that Mr. Simpson had stopped taking arthritis medicine to let his hands swell so that they would not fit the gloves in court. Mr. Simpson’s lawyer Yale L. Galanter denied Mr. Gilbert’s claims, calling him delusional.

In 2016, more than 20 years after his murder trial, the story of O.J. Simpson was told twice more for endlessly fascinated mass audiences on television. “The People v. O.J. Simpson,” Ryan Murphy’s installment in the “American Crime Story” anthology on FX, focused on the trial itself and on the constellation of characters brought together by the defendant (played by Cuba Gooding Jr.). “O.J.: Made in America,” a five-part, nearly eight-hour installment in ESPN’s “30 for 30” documentary series (it was also released in theaters), detailed the trial but extended the narrative to include a biography of Mr. Simpson and an examination of race, fame, sports and Los Angeles over the previous half-century.

A.O. Scott, in a commentary in The New York Times, called “The People v. O.J. Simpson” a “tightly packed, almost indecently entertaining piece of pop realism, a Dreiser novel infused with the spirit of Tom Wolfe” and said “O.J.: Made in America” had “the grandeur and authority of the best long-form fiction.”

In Leg Braces as a Child

Orenthal James Simpson was born in San Francisco on July 9, 1947, one of four children of James and Eunice (Durden) Simpson. As an infant afflicted with the calcium deficiency rickets, he wore leg braces for several years but outgrew his disability. His father, a janitor and cook, left the family when the child was 4, and his mother, a hospital nurse’s aide, raised the children in a housing project in the tough Potrero Hill district.

As a teenager, Mr. Simpson, who hated the name Orenthal and called himself O.J., ran with street gangs. But at 15 he was introduced by a friend to Willie Mays, the renowned San Francisco Giants outfielder. The encounter was inspirational and turned his life around, Mr. Simpson recalled. He joined the Galileo High School football team and won All-City honors in his senior year.

In 1967, Mr. Simpson married his high school sweetheart, Marguerite Whitley. The couple had three children, Arnelle, Jason and Aaren. Shortly after their divorce in 1979, Aaren, 23 months old, fell into a swimming pool at home and died a week later.

Mr. Simpson married Nicole Brown in 1985; the couple had a daughter, Sydney, and a son, Justin. He is survived by Arnelle, Jason, Sydney and Justin Simpson and three grandchildren, his lawyer Malcolm P. LaVergne said.

After being released from prison in Nevada in 2017, Mr. Simpson moved into the Las Vegas country club home of a wealthy friend, James Barnett, for what he assumed would be a temporary stay. But he found himself enjoying the local golf scene and making friends, sometimes with people who introduced themselves to him at restaurants, Mr. LaVergne said. Mr. Simpson decided to remain in Las Vegas full time. At his death, he lived right on the course of the Rhodes Ranch Golf Club.

From his youth, Mr. Simpson was a natural on the gridiron. He had dazzling speed, power and finesse in a broken field that made him hard to catch, let alone tackle. He began his collegiate career at San Francisco City College, scoring 54 touchdowns in two years. In his third year he transferred to Southern Cal, where he shattered records — rushing for 3,423 yards and 36 touchdowns in 22 games — and led the Trojans into the Rose Bowl in successive years. He won the Heisman Trophy as the nation’s best college football player of 1968. Some magazines called him the greatest running back in the history of the college game.

His professional career was even more illustrious, though it took time to get going. The No. 1 draft pick in 1969, Mr. Simpson went to the Buffalo Bills — the league’s worst team had the first pick — and was used sparingly in his rookie season; in his second, he was sidelined with a knee injury. But by 1971, behind a line known as the Electric Company because they “turned on the Juice,” he began breaking games open.

In 1973, Mr. Simpson became the first to rush for over 2,000 yards, breaking a record held by Jim Brown, and was named the N.F.L.’s most valuable player. In 1975, he led the American Football Conference in rushing and scoring. After nine seasons, he was traded to the San Francisco 49ers, his hometown team, and played his last two years with them. He retired in 1979 as the highest-paid player in the league, with a salary over $800,000, having scored 61 touchdowns and rushed for more than 11,000 yards in his career. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985.

Mr. Simpson’s work as a network sports analyst overlapped with his football years. He was a color commentator for ABC from 1969 to 1977, and for NBC from 1978 to 1982. He rejoined ABC on “Monday Night Football” from 1983 to 1986.

Actor and Pitchman

And he had a parallel acting career. He appeared in some 30 films as well as television productions, including the mini-series “Roots” (1977) and the movies “The Towering Inferno” (1974), “Killer Force” (1976), “Cassandra Crossing” (1976), “Capricorn One” (1977), “Firepower” (1979) and others, including the comedy “The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad” (1988) and its two sequels.

He did not pretend to be a serious actor. “I’m a realist,” he said. “No matter how many acting lessons I took, the public just wouldn’t buy me as Othello.”

Mr. Simpson was a congenial celebrity. He talked freely to reporters and fans, signed autographs, posed for pictures with children and was self-effacing in interviews, crediting his teammates and coaches, who clearly liked him. In an era of Black power displays, his only militancy was to crack heads on the gridiron.

His smiling, racially neutral image, easygoing manner and almost universal acceptance made him a perfect candidate for endorsements. Even before joining the N.F.L., he signed deals, including a three-year, $250,000 contract with Chevrolet. He later endorsed sporting goods, soft drinks, razor blades and other products.

In 1975, Hertz made him the first Black star of a national television advertising campaign. Memorable long-running commercials depicted him sprinting through airports and leaping over counters to get to a Hertz rental car. He earned millions, Hertz rentals shot up and the ads made O.J.’s face one of the most recognizable in America.

Mr. Simpson, in a way, wrote his own farewell on the day of his arrest. As he rode in the Bronco with a gun to his head, a friend, Robert Kardashian, released a handwritten letter to the public that he had left at home, expressing love for Ms. Simpson and denying that he killed her. “Don’t feel sorry for me,” he wrote. “I’ve had a great life, great friends. Please think of the real O.J. and not this lost person.”

Alex Traub contributed reporting.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at nytnews@nytimes.com.Learn more

Robert D. McFadden is a Times reporter who writes advance obituaries of notable people. More about Robert D. McFadden

. . .

“O.J., Made in America, Made by TV”

By James Poniewozik, Chief TV critic for The New York Times, April 11, 2024

In O.J. Simpson’s life and trials, television was a spotlight, a microscope and a mirror.

One of the strangest quotes I can remember associated with O.J. Simpson came from the broadcaster Al Michaels during the notorious freeway chase in 1994. Michaels, a sports commentator now covering the flight from the law of one of America’s biggest celebrities, said that he had spoken with his friend Simpson on the phone earlier. “Al,” Michaels recalled him saying, “I have got to get out of the media business.”

For a man who was about to be arrested and charged with the murder of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ron Goldman, it was an odd statement. But it was accurate. Simpson, during and after his pro football career, was a creature of the media business. With the freeway chase, and the acrimonious trial on live TV, he would essentially become the media business. Simpson, who died Wednesday at age 76, was one of the most-seen Americans in history.

What did people see when they looked at O.J. Simpson? A superstar, a killer, a hero, a liar, a victim, an abuser, an insider, a pariah — often many of these at once. In his fame and infamy, he was an example of what celebrity could make of a person and a symbol of what the media could make of a country.\

Simpson’s football career made him a TV star in itself, as he became the first N.F.L. running back to rush for more than 2,000 yards in a season, with the Buffalo Bills. But he found his way into mass-market stardom during the commercial breaks, doing endorsements for RC Cola, Chevrolet and, most famously, Hertzrental cars.

As the documentary “O.J.: Made in America” would later detail, race was a subtext of Simpson’s fame, even in his pitchman days. There was a sense of social relief in having white America, after the civil-rights battles of the 1960s, embrace a charismatic Black star. It felt good for the country to like O.J.

The Complex Life of O.J. Simpson

- Acting Fame: Before O.J. Simpson became synonymous with the sensational murder trial that riveted the nation in the mid-1990s, he was a football star turned Hollywood fixture who played roles as varied as an astronaut, a comic detective and a fake priest.

- A Turbulent Era: From the car chase to the verdict, the murder case became an inextricable part of Los Angeles history in the 1990s, and Angelenos to this day still ponder what happened.

- Living With the Aftershocks: Simpson tried to shed his Blackness, a writer muses, but his all-consuming murder trial put the historically lurid American psyche on full display.

- The Kardashian Connection: Long before the Kardashians became a star attraction on reality television, the family name first came to prominence when Simpson was on trial.

But it also required a complex negotiation, particularly in his most famous ad campaign, for Hertz. There was anxiety over how white viewers would take the image of a powerful Black man running through an airport — would it be thrilling or threatening? The commercials made sure to include white onlookers cheering “Go, O.J., go!” as if to validate his passport to mainstream stardom.

Acting roles followed, in “Roots,” the “Naked Gun” movies, the early HBO sitcom “First and Ten.” His fictional and pitchman roles would play up his image of innocuous charisma — an image that would echo surreally in his televised trial and the public reaction to it.

The murder case would show electronic media’s power to bring a country together and to rip it apart. The low-speed chase on the Southern California freeway was one of those where-were-you-when monoculture moments, like an earthbound perversion of the moon landing. It happened on a Friday night, interrupting Game 5 of the N.B.A. finals, riveting tens of millions of viewers, none of them — at home or in the broadcast studios — knowing if they were about to witness a death on live TV.

But amid this classic mass-media, global-village moment, there were signs that the case was already becoming something more surreal and disjointed, a macabre carnival that would consume TV. People showed up on the freeway with signs and cheers, as if to an N.F.L. playoff game. A prank caller, evidently a Howard Stern fan, got on the air on ABC and saluted the anchor Peter Jennings with a hearty “Baba Booey.”

The trial, once it began, was the biggest series on TV, although even that feels like an understatement. What part of TV, in 1994 and 1995, wasn’t the O.J. Simpson trial? It was “The Tonight Show,” “Larry King Live” and Norm Macdonald’s “Weekend Update” on “Saturday Night Live.” It was the first topic of conversation in the morning and the last, on cable news, at night. It inspired a “Seinfeld” episode and a fantasy sequence on “Roseanne” in which the prosecutor Marcia Clark (Laurie Metcalf) crawls out of the TV to talk to Roseanne Conner (Roseanne Barr), who provides her with the missing murder weapon.

The trial was all TV. It was every kind of TV. It was a soap opera. It was a legal thriller. It was an interactive whodunit before the age of murder podcasts. It was a social drama that exposed racial chasms and the flaws of the legal system. It was a dark comedy with buffoons, villains and comic-relief figures.

It was a tragedy too, of course, and viewers could not agree which part of it was a tragedy, and that too was the tragedy.

It was also a preview of coming attractions. It was the model for the all-in immersion coverage that 24-hour news would apply to everything from wars to missing-persons cases to sex scandals. All-O.J.-all-the-time would seamlessly become all-Clinton-Lewinsky-all-the-time, complete with legal commentators reprising their roles.

But even as the Simpson case showed the media’s power to plunge us all into the same story, it also revealed how different communities could inhabit different realities. We could watch the same trial, with the same testimony, but disagree not just on the proper verdict but on the stakes of the case.

It was open-and-shut or it was built on fraud. It was about domestic violence against women or it was about racism. It was about how the rich and famous were above the law or about how Black defendants were beneath it. It was about the crimes of a person or the crimes of a system.

Like the home audiences caught reacting to the verdict, some cheering and some wailing, we would become a split-screen nation. Eventually, with TV news augmented by partisan outlets and social media, people would come to many more stories — elections, wars, pandemics — encased in their own ecosystems, listening to their own experts, believing their own facts.

As for the Simpson case, TV would eventually catch up with the more complicated reality. In 2016 both the “Made in America” documentary and the mini-series “The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story” laid out the case against Simpson as well as the trial’s racial-historical context. Taken together, they suggested that you could believe Simpson guilty without believing the system innocent.

Nuance and complexity are still possible. But they tend to work on the slow, patient timetable of history. As far as the daily news is concerned, on the other hand, we still live in the world that the Simpson trial created. This week, O.J. Simpson finally left the media business. The rest of us are stuck with it.

James Poniewozik is the chief TV critic for The Times. He writes reviews and essays with an emphasis on television as it reflects a changing culture and politics. More about James Poniewozik

. . .

“How OJ Simpson’s ‘trial of the century’ opened the door to Trump’s presidency”

Analysis by Oliver Darcy, April 11, 2024, CNN

The O.J. Simpson trial changed the media landscape. AFP/Getty Images

Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared in the “Reliable Sources” newsletter. Sign up for the daily digest chronicling the evolving media landscape here.New YorkCNN —

O.J. Simpson gripped the nation’s attention for a final time Thursday.

As breaking news banners and push alerts crashed onto screens from coast to coast, stunning millions with news of the former National Football League star’s death, the moment produced one last Simpson-centric collective event for the national consciousness.

But the impact the former Heisman Trophy-winning running back, who spellbound the nation as he was tried and ultimately acquitted for the gruesome murder of his ex-wife, left imprinted on America’s media environment will endure long beyond his death.

In fact, it is not out of the question to wonder: Would Donald Trump have ever risen to political power and become president without Simpson?

On its surface, that might seem far-fetched. But the impression that Simpson’s all-consuming trial had on shaping the modern media environment cannot be overstated. From the moment Simpson led police on a low-speed chase down a Los Angeles freeway after being charged with the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman, the media landscape was never the same.

Simpson’s ensuing trial in 1995 drew astonishing audience interest, with an unprecedented 150 million people tuning in on October 3 to watch the stunning verdict delivered live on television. The extraordinary attention the case generated helped launch the careers of a generation of household media stars, including Jeffrey Toobin, Nancy Grace, Greta Van Susteren, Dan Abrams, Harvey Levin, Gregg Jarrett and scores of others.

California Highway Patrol chase Al Cowlings, driving, and O.J. Simpson, hiding in rear of white Bronco on the 91 Freeway, just West of the I5 freeway. The chase ended in Simpson’s arrest at his Brentwood home. Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

The trial was also a milestone for the use of live TV cameras in the courtroom, transforming a typically closed-to-the-public process of justice into a cultural and entertainment spectacle that is still widely known as the Trial of the Century. Judge Lance Ito’s decision still resonates to this day, with judges often criticizing the “circus” atmosphere created by the trial as they weigh whether to allow the public to view such proceedings.

But the most consequential effects the trial had on American life were far broader. Simpson’s trial gave way to a media landscape dominated by salacious reality television and talking head-driven cable news.

Not only did Simpson’s trial catapult Robert Kardashian (and thus the entire Kardashian family) to fame, it also served as the first major reality television show to hypnotize the nation, giving way in later years to a number of programs aimed at capitalizing off unscripted high-drama.

Meanwhile, the wall-to-wall coverage of Simpson’s legal showdown, having entranced the nation, delivered a hefty viewership boost to outlets such as CNN and Court TV, helping to cement cable’s role as a destination for live news. Prior to the legal drama, Americans generally relied on the nightly newscasts for their daily dose of headlines. But the Simpson trial produced endless hours of courtroom theater, prompting viewers to tune in before the likes of Peter Jennings and Tom Brokaw made their way to air.

RELATED VIDEOO.J. Simpson’s death: the case that marked the 20th Century

In fact, according to a 1995 report in The New York Times, the surge in cable television viewership was so significant that it actually reduced the audience for the three broadcast nightly news programs. Andy Lack, then president of NBC News, said the impact was so pronounced that he worried about the Peacock network taking a “significant economic hit.”

The Simpson trial’s footprint on cable news did not stop there. According to media historian and University of Maine Communications and Journalism professor Michael Socolow, the trial helped persuade Rupert Murdoch into launching Fox News. Socolow said the Australian media mogul “grew enraged” watching CNN founder Ted Turner “rake in” an estimated $200 million from the live coverage of Simpson’s trial. And, to that end, Socolow said Murdoch was energized to launch his right-wing alternative in 1996 to grab his own slice of the lucrative pie.

It’s difficult to imagine Trump being elected to the White House without the three-legged stool that Simpson’s trial played a crucial role in building. Is there a Trump presidency without reality television? Or cable news? Or, especially, Fox News?

Trump exploited each of those branches of the post-Simpson media environment to gain fame. And then he ultimately used them to seek — and hold onto — political power.

“Simpson proved enormous profits could be generated from high ratings from programming that did not require actors and writers and sets. Reality TV had started earlier, but after Simpson there was a massive profusion of ‘Reality TV,’” Socolow said in an email. “That’s how ‘The Apprentice’ gave Donald Trump a comeback in American culture, and he rode his reality TV stardom to the White House.”

- “Brooks and Capehart on Trump’s decision to launch strikes on Iran”, PBS NewsHour

- Issue of the Week: War

- “The Original”, The New Yorker

- “Big Change Seems Certain in Iran. What Kind Is the Question”, The New York Times

- “Trump Says War Could Last Weeks and Offers Contradictory Visions of New Regime”, The New York Times

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017