Issue of the Week: War, Human Rights, Economic Opportunity, Hunger, Disease, Population, Environment, Personal Growth

Seventy Miles In Hell: The Darién Gap, The Atlantic, September 2024

The End Of Civilization As We Knew It: Part Twenty-Five

Eighty-five years ago today, the Nazis invaded Poland, starting World War Two.

Today, in Germany, for the first time since the end of World War Two, the extremist right wing AfD party with roots in Nazi ideology became the strongest force in a state parliament. “The AfD’s success is largely rooted in the former communist East, where the party has capitalized on anti-immigration sentiment and skepticism toward Germany’s military support for Ukraine”, Newsweek reports. Boiling under the surface for decades has been the promise of the fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification failing to be met. The basics of investment in economic opportunity in the East compared to the more proseprous West have not ocurred. The lack of equality and economic security that underpinned Hitler’s rise and fall and Soviet and East German communism’s rise and fall are playing out again in an historic vicious cycle. The scapegoats, the alliances between democratic forces and authoritarian forces, are manipulated and repeated in an endless hell. Germany at large is still committed to democracy and against any resurgence of the influences that led to World War Two. But the warning signs are flashing.

They are flashing everywhere. Germany is late to the dance. It has, with virtually all of Europe, the US and others supported Ukraine against Putin’s dictatorial, anti-democratic and anti-human rights aggression and attempt to reassert the Soviet/Russian empires. Until recently it was the most open and generous in bringing in and supporting Syrian refugees from Putin’s support of the Syrian butcher/dictator Assad, war against him by his own people originally fighting for freedom in the Arab Spring, and devolving into various wars with and between extremist groups and surrounding nations. The Syrian people killed by the hundreds of thousands and millions, the great majority, displaced within and around the world. The German people, initially the most welcoming, eventually tired of the cost. Which is what happens when everything is connected and the sources of the problems and needed solutions are not addressed, globally and definitively.

Instead the contagion spread, as it always has throughout history. The endless struggle between the powerful and powerless, the need to feed your family, the need to be secure in basic rights.

War is raging around the world today. No one called it World War Two when the Spanish Civil War started or the Nazis marched into Austria or the Japanese invaded China. These things congealed and became World War Two because of action and lack of action.

It’s happening again now–has been for some time. World War Three is for all practical purposes here, congealing, waiting to be officially and historially named. If there is any history after. If the razor’s edge between not allowing nuclear weapons to be used as blackmail into slavery, or to be actually used, is successfully walked. And even without, if all the other means of killing do not kill us all.

Wars are happening everywhere–more threatentng and more happening all the time. More than since World War Two.

And as they have throughout history, as all violence and conflict have throughout history, at their root is human misery, the using and crushing of the many by the few, by the evil pathology of addiction to riches and resources and power.

World War Three is here.

Unless the right persons, here, there and everywhere are put in positions of responsibility and authority, and the wrong persons prevented from being in these positions.

The cover story in the new Atlantic Monthly, and the cover picture, is the story at the root of all misery and violence and war–the faces are the faces of this from the beginning of time. The journalist for the story, Caitlin Dickerson–who journeyed through the Darién Gap, the seventy miles from hell that migrants by the hundreds of thousands are going through every day to escape worse hells to come to the nation, the US, that the Statue of Liberty gave it’s promise to–must be saluted for her courage and her unsurpassed skill in explaining all the forces at play and in making the pages breathe with life and death and humanity.

The article, Seventy Miles In Hell, follows below.

While Dickerson was coming north in December, many of the migrants she was with were crossing the Rio Grande at El Paso, where Keith Blume, the founder of Planet Earth Foundation and Clara Lippert, the project director of the Foundation, were waiting to interview them on film on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. The Issue of the Week at year’s end with photos, link to film and text on the experience and the issue, including the overt Nazi ideology embedded in the words of a candidate for president of the US, also follow.

Following this is the first part of The End Of Civilization As We Knew It, telling the story of what has happened on the planet since 2016, and well before, and since–at a point when Keith Blume and Lisa Blume, Directors of the Foundation, then, for decades at that point, and still, were in London working to end the infliction of the ultimate violence of the powerful on the powerless, child sexual abuse. All is intertwined. The worst options of what was to come in that reflection have all happened and are happening now, all over the world. This is not a statement of prophetic power uttered with pride, but an expression of heartbreak and continued warning. The end of life on earth really could be here. Yet the ultimate power of good, strategic intelligence for survival and commitment to lay our lives down if need be as the best of our ancestors have shown us must be done sometimes for human rights and human needs to be secure, is still a choice each of us and all of us can and must make.

. . .

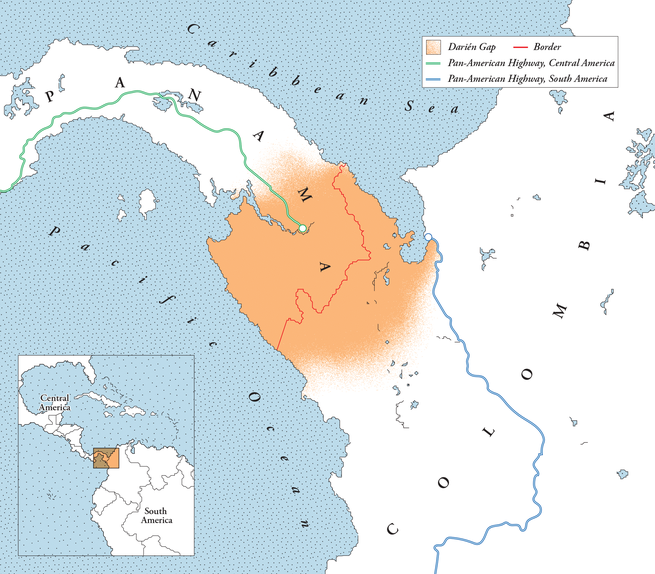

The Darién Gap was once considered impassable. Now hundreds of thousands of migrants are risking treacherous terrain, violence, hunger, and disease to travel through the jungle to the United States.

By Caitlin Dickerson, Photographs by Lynsey Addario, September Edition, Atlantic Monthy

They gathered in the predawn dark. Bleary-eyed children squirmed. Adults lugging babies and backpacks stood at attention as someone working under the command of Colombia’s most powerful drug cartel, the Gulf Clan, shouted instructions into a megaphone, temporarily drowning out the cacophony of the jungle’s birds and insects: Make sure everyone has enough to eat and drink, especially the children. Blue or green fabric tied to trees means keep walking. Red means you’re going the wrong way and should turn around.

Next came prayers for the group’s safety and survival: “Lord, take care of every step that we take.” When the sun peeked above the horizon, they were off.

More than 600 people were in the crowd that plunged into the jungle that morning, beginning a roughly 70-mile journey from northern Colombia into southern Panama. That made it a slow day by local standards. They came from Haiti, Ethiopia, India, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Venezuela, headed north across the only strip of land that connects South America to Central America.

The Darién Gap was thought for centuries to be all but impassable. Explorers and would-be colonizers who entered tended to die of hunger or thirst, be attacked by animals, drown in fast-rising rivers, or simply get lost and never emerge. Those dangers remain, but in recent years the jungle has become a superhighway for people hoping to reach the United States. According to the United Nations, more than 800,000 may cross the Darién Gap this year—a more than 50 percent increase over last year’s previously unimaginable number. Children under 5 are the fastest-growing group.

The U.S. has spent years trying to discourage this migration, pressuring its Latin American neighbors to close off established routes and deny visas to foreigners trying to fly into countries close to the U.S. border. Instead of stopping migrants from coming, this approach has simply rerouted them through the jungle, and shifted the management of their passage onto criminal organizations, which have eagerly taken advantage. The Gulf Clan, which now calls itself Ejército Gaitanista de Colombia, effectively controls this part of northern Colombia. It has long moved drugs and weapons through the Darién Gap; now it moves people too.

Everyone who works in the Darién Gap must be approved by the cartel and hand over a portion of their earnings. They have built stairs into hillsides and outfitted cliffs with ladders and camps with Wi‑Fi. They advertise it all on TikTok and YouTube, and anyone can book a journey online. There are many paths through. The most grueling route is the cheapest—right now, about $300 a person to cross the jungle on foot. Taking a boat up the coast can cost more than $1,000.

Caitlin Dickerson: There’s no such thing as a border czar

I went to the Darién Gap in December with the photographer Lynsey Addario because I wanted to see for myself what people were willing to risk to get to the United States. Before making the journey, I spoke with a handful of journalists who had done so before. They had dealt with typhoid, rashes, emergency evacuations, and mysterious illnesses that lingered for months. One was tied up in the forest and robbed at gunpoint. They said that we could take measures to make the journey safer but that ultimately, survival required luck.

Each year, Panamanian authorities remove dozens of bodies from the jungle. Far more are swallowed up by nature. These deaths are the result not only of extreme conditions, but also of the flawed logic embraced by the U.S. and other wealthy nations: that by making migration harder, we can limit the number of people who attempt it. This hasn’t happened—not in the Mediterranean, or the Rio Grande, or the Darién Gap. Instead, more people come every year. What I saw in the jungle confirmed the pattern that has played out elsewhere: The harder migration is, the more cartels and other dangerous groups will profit, and the more migrants will die.

The night before we set out, a Venezuelan father named Bergkan Rhuly Ale Vidal paced around a camp at the jungle’s mouth, packing and repacking his family’s bags. He and his partner, Orlimar, had their children with them: 2-year-old Isaac and 8-year-old Camila. Even in the dark the air was sweltering, and Bergkan’s mind was spinning with worry. What if one of the children fell and hurt themselves, or came down with a fever? What if one was bitten by a snake? In trying to salvage his family’s future, had he gravely miscalculated?

The first day, the path was studded with boulders and trip-wired with vines. It weaved across a river so many times that I quickly gave up on dumping out my rubber boots, because they would only fill again minutes later. Bergkan’s family’s tennis shoes were already ripped and disintegrating. The hills were slick with mud and so steep that we were often not so much walking as climbing on our hands and knees, holding on to mangled roots.

We passed stands selling bottles of water and Gatorade, two for $5. Porters, known as mochileros, circled the family, hawking their services. “We carry backpacks, we carry children!” they chanted. They charge roughly $100 a day, and also barter with migrants for items in their backpacks. Orlimar tried trading a pair of old headphones for new boots, but was rejected. A couple of times, she and Bergkan lost patience with the porters and yelled, “We have no money!”

Midmorning, we reached the route’s toughest hill. After half an hour of climbing, Bergkan crashed to the ground, his chest heaving. Orlimar threw down her belongings. “What do you have in that bag?” he asked her.

“Shoes—sandals,” Orlimar said in a voice so soft, she was barely audible.

Bergkan told her to dump any weight she could. She began pulling out clean clothes. “Someone else will be able to use them,” he said. But the other families nearby were also unloading supplies. The people who had the strength to keep hiking charged past us, staring straight ahead, as if exhaustion were an illness that they might catch just by looking at it.

Crossing the jungle can take three days or 10, depending on the weather, the weight of your bags, and pure chance. A minor injury can be catastrophic for even the fittest people. Smugglers often downplay how many days the journey will take—Bergkan had been told to plan for two. A few hours into the trip, he began to realize that they were nowhere near as deep into the jungle as they needed to be, which meant they might not have enough food to get them out.

Bergkan and Orlimar had planned for a different life. They’d met as teenagers and gone to college together, Orlimar studying nursing and Bergkan engineering. But Venezuela’s economy imploded in 2014, the result of corruption and mismanagement. Then an authoritarian crackdown by the leftist president, Nicolás Maduro, led to punishing American sanctions. The future they had been working toward ceased to exist. In the past decade, at least 7.7 million Venezuelans have fled.

Bergkan and Orlimar spent five years taking any job they could get, first in Venezuela and then in Peru, while they watched their friends and classmates leave, one after another, for the United States. Then Orlimar’s cousin Elimar, who was like a sister to her, came to them with an offer: Her boyfriend, who was living in Dallas, would pay for Bergkan’s family to take the cheapest route across the jungle, if Elimar and her two children—who were 6 and 8—could go with them. “No one in Venezuela can lend you money, much less that amount,” Bergkan told me. “It was our moment.” They planned to stay in the U.S. only until Venezuela’s economy recovered and they could return home.

We trudged uphill for hours. Isaac teetered on Bergkan’s shoulders. Gripping his son’s feet, Bergkan adopted a strategy of sprinting up a stretch of hill for about 30 seconds, then collapsing again. His limbs shook and his face turned an ominous shade of purple. “The weight you carry is in your mind,” he said at one point, giving himself a pep talk. Camila stopped cold a couple of times, holding up the long line of people behind her, and yelled, “Mommy, I can’t!”

Around 1 p.m., Isaac fell asleep, his limp body rocking back and forth. “It feels like his weight has tripled,” Bergkan told Orlimar. They sat down on a hillside to regroup. Elimar tried coaxing her nephew awake with lollipops, but he was unresponsive. Other parents stopped to ask if he was okay. Bergkan pulled a packet of electrolyte powder out of his bag. He mixed it with water, then shook Isaac awake and told all four children to down it. “We’re going to get you out of here,” Bergkan said, more to himself than to anyone else.Guides and porters follow the migrants with their iPhones rolling, asking, “Have we treated you well?” They post the videos on social media, selling trips across the jungle as if they were joyful nature walks.

Eventually, a porter explained that we were moving too slowly to make it to Panama that day; we would have to sleep at a camp for stragglers. When we arrived, we saw wooden platforms for tents, bucket showers and toilets, and a couple of outdoor kitchens with Colombians serving plates of chicken and rice—all for a price. People around us began purchasing Wi‑Fi for $2 an hour so they could ask relatives to send them more money; transfers carried a 20 percent fee. Elimar began circulating through the camp, asking other Venezuelans for a loan to help her contact her boyfriend. Bergkan, Orlimar, and their children sat down and rubbed their aching limbs. They had no one to call.

In the three trips I took to the Darién Gap over the course of five months, I saw new bridges and paved roads appear deeper in the jungle, Wi‑Fi hotspots extend their reach, and landmarks that were previously known only by word of mouth appear on Google Maps. Looking down at a thrashing river, I held on to ropes that made it safer—slightly—to creep across sheer rock faces behind parents with crying babies strapped to their chests.

Guides and porters follow the migrants in the jungle with their iPhones rolling, asking, “Do you feel good?” and “Have we treated you well?” They film incessantly during the first day of walking, when people are still able to conjure a smile. (Even I ended up in one of their videos.) They post the videos on social media, selling trips across the jungle as if they were joyful nature walks. The profit motives of the cartel have become yet another factor fueling migration.

The UN has tried to counteract these messages by stationing migration officials at bus stations and other checkpoints along the way to the Darién Gap; they warn people of the dangers ahead and try to persuade them to reconsider. Those efforts have been largely ineffective. “People come with tunnel vision, like, ‘I must get to the United States,’ ” Cristian Camilo Moreno García, a UN migration official based in northern Colombia, told me. “Turning back is not an option.”

On the second morning of our journey, about 150 people filed out of the camp and waited for the sun to rise before they started walking. Bergkan and his family ate nothing; they needed to conserve the few cans of tuna and packages of cookies they had left. The children were still in their pajamas, some of their only remaining clean clothes. Two women stood at the end of the line collecting final payments and then handing each person a wristband, the kind you might get at a music festival, to show that they had paid. “Please take out your money so that we can move you along faster!” one yelled.

We walked along a narrow ridge with steep cliffs dropping off on either side, all of us trudging much slower than the day before. After about an hour and a half, Elimar’s son, Luciano, crumpled to the ground. The adults gathered around him. “Take off his sweater—he’s suffocating!” one yelled. Without a word, one of the porters Lynsey and I had hired hoisted the child onto his shoulders, apparently unable to watch Luciano struggle any longer. He dashed up the slope and out of sight. Elimar looked defeated but also relieved to have one fewer child to worry about, at least until we made it to the next stopping point.

Word spread down the line that we were approaching the border with Panama. The porters, who had boisterously peddled their services for two days, started to go quiet. Profiting from migration is illegal in Panama, and can carry a sentence of more than 12 years in prison. Panama’s border patrol, known as SENAFRONT, has been enforcing those laws aggressively against people who sell migrants bottles of water, carry their backpacks, or serve as guides. The porter who had picked up Luciano revealed the scar on his chest from a bullet wound that he said he’d sustained on a previous trek, when officers had sprayed bullets into Colombia. He said that we should be prepared to run. (When I asked Jorge Gobea, the head of the agency, if his officers ever shot across the border at Colombian guides, he told me, “If someone armed fights Panama authorities, we use force.”)

The border was marked by a Panamanian flag and piles of trash. Some people posed for pictures and celebrated half-heartedly, unsure if they were nearing the end of the journey or still at the beginning. Orlimar made the sign of the cross, then sat down with her head between her knees. Elimar was the first to notice the Panamanian border guards approaching and warned us: “Get down! Get down!”

Lynsey and I wished the family well and, along with the Colombian porters, sprinted back down the mountain.

After leaving bergkan and his family at the border, we doubled back to take the second primary land route through the Darién Gap. This one was said to be slightly easier, and cost more as a result. We had secured permission this time from the Panamanian government to follow it all the way through to the end.

After a day of hiking, we slept at another camp, where we fell in with a large group led by a Venezuelan mother of three named María Fernanda Vargas Ramírez, who had been living with her family in Chile. The original members had met on social media and picked up more travelers on their way to the jungle, until the group included 21 people, all but one of them Venezuelan. People crossing the Darién Gap tend to develop family-like bonds with other migrants they meet along the way. They look out for one another’s kids and count off when they pause to rest, making sure no one gets lost. But this group was especially close. Its members shared food and water freely and said they planned to stay together all the way to the United States.

As we neared the Panamanian border a second time, a Colombian guide who was preparing to turn back asked a few of us to look out for a woman named Cataña, whom he’d recently led down the same path but who had never come out of the jungle. He took out his phone and showed us pictures of her sitting on a bus and in what looked like a transit station. She appeared pensive, unsure what to think about the voyage ahead. “She was very slow, so the others in the group left her behind,” the guide said.

“I can’t imagine this group doing something like that,” I replied.

“We’ll see,” he said. People lose patience quickly when they’re running out of food.

This route was newer and hadn’t yet been trampled by hundreds of thousands of people. The foliage closed in from all sides, making the path hard to discern. We stepped over jaguar tracks and passed a Bothrops, the deadliest viper in South America, coiled around a branch near our ankles. In a ravine, we saw what looked like the scene of a person’s bad fall: a tennis shoe, a skull, and the bones of a leg with a bandage wrapped around the knee like a tourniquet.

Once we entered Panama, we faced new threats: robbery and sexual assault. Most of these attacks happen at the hands of Indigenous Panamanians. For years their villages were routinely ransacked by narco traffickers and paramilitary groups. Some Indigenous Panamanians took up arms in self-defense, or got involved in trafficking themselves. The government did little to protect them then and does little to stop them now.

The porters we had paid to continue on with us told us to stay close together because bandits were thought to be intimidated by large groups. Later, we learned that was false—they were in fact targeting large groups, perhaps because it was more efficient than robbing a handful of people at a time. Our anxiety grew when we passed a couple of abandoned backpacks. We pushed through thicker and thicker brush until I realized there was no longer any sign of a path. One porter accused another of leading us astray. They started arguing, until a third hissed, “No yelling!” We turned around, but a bottleneck formed in front of a fallen tree trunk. One of the porters shouted for us to hurry: “Grab the kids and go!”

At midday, we reached a camp known as La Bonga, the only place in the jungle where the Panamanian government was allowing people to sell food and water to migrants. Lynsey and I met up with a dozen border-patrol officers who had been assigned to tail us, as a condition of our making the trip. We trudged through mud and rivers for another six hours before stopping for the night. It rained on and off; the adults, sharing a handful of tents, would have to sleep in shifts.

One of the women, a Venezuelan named Adrianny Parra Peña, climbed into an airless tent, her face smeared with dirt. She and her husband had been helping María Fernanda by essentially taking custody of her 9-year-old twin boys, carrying them across rivers and lifting them up steep inclines. Adrianny told me that she’d wanted her own children but that this was the third time in six years that she and her husband had tried resettling, first in Peru, then Chile, and now, she hoped, the United States. “We are tired of all this migrating,” she told me. “This is no way to live.”

The next morning, we faced the route’s hardest obstacles, a series of rock faces. Ropes had been strung across some of them, but it was impossible to know which were secure enough to hold on to. “Oh my God, I can’t watch,” María Fernanda said when her 7-year-old daughter crossed the rock. She covered her eyes and shouted, “Hold on tight, my princess!”

When it was an 8-year-old girl named Katherine’s turn, she slipped and fell into the rocky river about 15 feet below. Her mother, who had been right behind her, stood frozen while one of the porters jumped into the water after her. Katherine emerged crying but uninjured. We started hiking again almost immediately—no one wanted to contemplate the near miss any longer than they had to.

The next day was the group’s fourth in the jungle and the 15th since leaving Chile. We came upon a fallen tree trunk covered in wet moss that we would have to cross like a balance beam above a racing river. I stopped short, certain that there was no way I would make it across without slipping. Then I noticed a little girl we’d never seen before standing alone, wide-eyed, seemingly unsure of what to do. One of the teenage boys in our group reached over, wrapped an arm around her belly, and carried her across. He placed her down unceremoniously on the other side and kept walking. I held my breath and stepped onto the log.

We started seeing abandoned tents and wondered if they meant that we were reaching the jungle’s edge, or if the people who’d left them had simply been too weak to carry even the most basic supplies. And for the first time, we saw people sitting by themselves on rocks and tree stumps, staring aimlessly into the distance, apparently deserted by their traveling companions. We crossed a river behind a family with three girls, two of whom were disabled. The eldest looked to be at least 10 but was swaddled like a baby in a sheet against her father’s chest, her long limbs flopping out. Her father slipped and face-planted, dunking them underwater. When they resurfaced, the girl was coughing and screaming. The father shook himself off, tightened the sheet, and kept going. Just off the path lay a decomposing corpse, tucked under a blanket.

The dozen Panamanian officers assigned to tail us started asking us to share the last of our food—until we ran out. They were exhausted and kept wanting to take breaks. The platoon’s medic chugged a bottle of saline solution. We’d given it to him, along with antivenom that required dilution, to hold on to as a precaution against snakebites. But the officer had a more urgent problem: diarrhea from drinking the river water.

Around midday, we reached a place called Tres Bocas, where three rivers combine—and where bodies tend to wash ashore toward the end of the rainy season. Many members of María Fernanda’s group had fallen far behind, along with half of the border-patrol officers. One officer warned us that we were still at least 13 miles from the jungle’s edge but that, because of the terrain, it would feel twice as long. We couldn’t wait for the others to catch up.For four hours, we alternated between speed-walking and running, far exceeding what I would have thought physically possible. We finally emerged from the canopy onto a rocky beach where hundreds of migrants were waiting. Many said they hadn’t eaten in days.We all climbed into motorized canoes driven by Indigenous people who charged $25 a person. Two hours later, as the sun set, we arrived in Bajo Chiquito, a community of about 200 people that—despite having no running water, electricity, or hospital—the Panamanian government had deemed an official reception point for people who make it out of the Darién Gap, and a key landmark amid the “controlled flow” of migration that it claims to have achieved.

The density of the jungle makes it difficult to contend at any one moment with the humanitarian catastrophe it contains, and the many policy failures that led people there. But all of that is on display in Bajo Chiquito, where the feeble systems for processing migrants are stretched dangerously thin.

Shaking from exhaustion, we climbed up a set of stairs that leads into the village. From sunrise to sunset, the entrance is packed with migrants waiting to be processed by government officials. Up to 4,000 people a day arrive here. Some have to be carried up the steps; others collapse when they reach the top.

Despite Panama having the highest per capita income in Latin America, its Indigenous people live in almost universally crushing poverty. Panamanian politicians are quick to decry how migration has changed the Indigenous way of life, but it has been a windfall for communities like Bajo Chiquito. While I was there, music blared as the migrants who had money bought food, Wi-Fi, toiletries, clean clothes, and tents. Residents walked around holding wads of American dollars, the de facto currency of the Darién Gap.

Most of the migrants I met in the processing line told me they’d been robbed by bandits at a checkpoint within a day’s walk of the community. The women said they’d been groped; some said they’d been digitally penetrated under the guise of a search for hidden cash. Panamanian border officers standing nearby showed no interest in investigating. Indigenous leaders say they have asked the government for help addressing crime against migrants, but the situation seems to be getting worse. In February, Doctors Without Borders published a report on sexual violence against migrants in the Darién Gap, showing a frequency more typical of war zones. Soon after, the government kicked the organization out of the area.

On the sides of houses in Bajo Chiquito, I saw missing flyers displaying the photograph of a 9-year-old Vietnamese boy with plump cheeks. Panamanian authorities had told me that children who become separated from their family in the jungle are pulled aside until the adults arrive. But within minutes of interviewing people in the processing line, I met a 5-year-old Ecuadorian girl who’d arrived with a group of strangers she’d met in the jungle. When it was their turn to be questioned, no one in the group admitted that they weren’t related to the girl. They had no documents for her, but the migration officers waved them through.

A long line of the sick and injured snaked around Bajo Chiquito’s sole medical clinic, which was opened to respond to the influx of migrants. In the open-air waiting room—a few dozen plastic chairs on a concrete slab—people vomited, nursed rashes and bloody wounds, and carried babies who’d had diarrhea for days. Doctors handed out a couple of pills for fevers or squirts of rash cream in plastic baggies, and called for the next patient.

Two women carried in a friend who had nearly drowned; she was mumbling and couldn’t lift her head. A nurse led them to a gurney and connected the woman to an IV while her three children watched in horror. The nurse returned a short while later and, though the woman was still incoherent, told the family that they would have to leave soon—the facility closed at 5 p.m. A couple of men who had just come out of their own appointments carried her to a tent as she moaned.

The next morning, migrants lined up again for canoes that would take them to a larger camp near the highway, from which they would depart for Costa Rica. Unaware that all of them would get a spot, they started shouting at one another in different languages about who had been first in line. “This happens every day,” an officer told me. I spotted the woman from the clinic asleep on a bench, her skin a greenish-gray color. Her youngest child, an 8-year-old boy, held her head in his lap, stroking her hair and swatting away flies. Her two older children were walking up and down the village, looking lost and debating what to do.

Suddenly, Lynsey and I heard screaming. We ran inside a pink house that was renting rooms to migrants and found a large family from China whom we had met at the clinic the day before. They’d had fevers for days and were sent away with ibuprofen. That morning the 70-year-old grandfather, Yenian Shao, had not woken up. His wife and daughter lay over his body, wailing and chanting.

Border-patrol officers called for a local investigator, who arrived an hour later. Using a translation app on his phone, Yenian’s son tried asking if his father’s body could be cremated or sent back to China, but he couldn’t understand the response. The authorities packed up Yenian’s body and lowered it down the side of a hill into a canoe. Yenian’s wife got in next, straddling her husband’s body bag, followed by the rest of their family. Residents were sweeping the streets of trash. Just across the river, the first new migrants of the day were arriving.

In april, we returned to Panama to visit a sleepy fishing village near the Colombian border called Puerto Obaldía. Its once brightly colored homes have weathered over the years. There are few ways to make money here. Migration used to be one of them.

For years, migrants had arrived in Puerto Obaldía on boats from Colombia. Locals sold them food, allowed them to camp, and charged them to arrange the next leg of their journey—either on charter flights to Panama City from a tiny airstrip, or in fishing boats up the coast, to another village with a paved road that connects to a highway out of the country. This lasted until 2015, when migration through the Darién Gap reached roughly 30,000 people for the first time in history, and the U.S. leaned on Panama to crack down. The border patrol began arresting residents and charging them with smuggling.When I asked one of our Colombian guides how the cartel would respond to the closing of this route, he replied, “Make another route.”

When we went, the town was in the middle of a mayoral election, plastered with posters of smiling candidates. They were all campaigning on a platform of bringing the migrants back, though none seemed to know how to do so. The candidates I interviewed, and other residents, acknowledged that at times the town had been overwhelmed. At one point in 2015, there were 1,500 migrants camped in this community of only about 600. But they insisted that the arrangement was better than the one that exists now—for them and for the migrants.

The boat rides never stopped; cartels simply took them over, labeling them a “VIP” option and charging upwards of $1,000 a person. Now the boats leave just after sunset, even when the seas are dangerously rough, and sometimes they capsize. At least five people have drowned this year, including an Afghan child.

“It’s the government’s fault that so many have died,” Alonsita Lonchy Ibarra Parra, one of the candidates, told me. Another, Luis Alberto Mendoza Peñata, said that the community had appealed to the authorities, asking why migrants can rest and refuel in Bajo Chiquito but not in their community. “We write letters. They don’t respond,” he told me. “If immigration is illegal in Panama, why is it allowed there, but not here?”

But the United States is pushing Panama and other Latin American countries to crack down more on migration, not less. Recently Panama agreed to accept $6 million from the U.S. for deportation flights. The U.S. has also been urging Panama to construct detention centers, like those that exist along the U.S.-Mexico border. Panama’s newly elected president campaigned on the promise to seal the Darién Gap completely. But an effort to do just that, announced by the U.S., Panama, and Colombia last year, had no discernible effect—more than half a million people made it through, the largest number to date. In June, the Panamanians installed a razor-wire fence across the border at the same spot where we had crossed. When I asked one of our Colombian guides what the cartel was going to do next, he replied, “Make another route.” Before the week’s end, someone had cut a hole in the fence, and migrants were streaming through.

Beyond the Darién Gap, migrants and their smugglers continue to find ways around the roadblocks set before them. Recently, hundreds of thousands of migrants have flown into Nicaragua, for example, which has bucked U.S. pressure to restrict visas.

Mari Carmen Aponte, the U.S. ambassador to Panama, and other State Department officials I interviewed said the American government was trying to balance deterrence with programs to keep migrants safe. They pointed to offices that the United States is opening throughout Latin America to interview people seeking refugee status. The U.S. hopes to approve as many as 50,000 this year to fly directly into the country, far more than in the past.

Key to these screenings, the officials told me, will be distinguishing between true refugees and economic migrants. But most people migrate for overlapping reasons, rather than just one. Many of the migrants I met in the Darién Gap knew which types of cases prevail in American immigration courts and which do not. They were prepared to emphasize whichever aspect of their story would be most likely to get their children to safety.

And too often, deterrence and protection are not complementary strategies, but opposing ones. When I told Aponte about my reporting in Puerto Obaldía, where Panama’s crackdown seemed only to hand migrants over to the cartel and force more of them into the jungle, she said she hadn’t thought about the situation in such stark terms before. She acknowledged that she was trying to make choices “between two extremes—none of which works.”

On that same trip to Puerto Obaldía, I learned that in January of this year, Panama had made what seemed like a concession to the locals, allowing them to open a small camp about a four-hour hike from the town. A group of officers agreed to accompany Lynsey and me there. On the way, a representative from the border patrol’s communications department had to stop several times to vomit from overexertion. After we arrived, the officers recovered while drinking cold Gatorade and eating a hot lunch of chicken and rice.

Nelly Ramírez, a 58-year-old woman from Venezuela, sat slumped on a bench. On her second day walking through the jungle with her daughter and four grandchildren, she had slipped on some leaves and broken her leg, and it was still oozing with pus. Other migrants had carried her to the camp while her family continued on. A woman working there had given her food and a hammock. She had no money and was panicking about what to do next. But if the camp hadn’t existed, she figured she would have died in the jungle alone.

Two days later, some of the same officers returned to the camp just after sunrise. They were not on their way to investigate people robbing and assaulting migrants in the jungle, or those who captain deadly boat rides for exorbitant fees. Instead, they declared that the people running the camp had been aiding and abetting human trafficking by selling food and Wi-Fi. They burned the camp down.

María fernanda’s group of 21 splintered before even making it out of the jungle, when some members were caught sneaking food they’d hidden after everyone said they’d run out. After passing through Central America, those who could afford it took express buses to Mexico City. The rest slept in shelters and on the streets. One of the poorest families was kidnapped in southern Mexico. They sent desperate messages to the group, begging for money. Most said they had nothing to spare.

Orlimar and her cousin Elimar are no longer speaking. They had a falling-out at a bus station in Honduras, when Elimar grew tired of waiting for Bergkan to scrounge together enough money to continue. She purchased tickets for herself and her own kids, and told Orlimar they were leaving just as they were called to board.

Bergkan had blown up, he said, accusing Elimar of taking advantage of him. “I told her, ‘You used me like a coyote! Like a mochilero to help you with the kids.’ ”

In Mexico City, Elimar applied for an interview with American immigration officials using U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s app CBP One, which was created to streamline arrivals at the border. But she lost patience after a month and found someone to shuttle her and the kids across the border illegally. They turned themselves over to immigration authorities and were given a court date in 2029. That long a wait is not unheard-of. They now live in an apartment complex on the outskirts of Dallas, where her children are enrolled in public school. Elimar cleans offices and her boyfriend works as a cook at a chain restaurant.

Once Bergkan’s family made it to southern Mexico, they rode in a series of vans called combis, which are the cheapest way to travel on the country’s dangerous rural highways. They say they lost count of the times that narcos, police officers, and Mexican immigration officials boarded the vans and demanded bribes. They made Central Americans and Caribbeans pay more than the Venezuelans—everyone knew they were the poorest. The last group of armed men kept their request modest: “100 pesos per person,” they said, about $6. “It’s not that much.” Sixteen days after the family left Bajo Chiquito, they arrived in Mexico City.

Bergkan is now working odd jobs; he has bound textbooks in a factory and done construction in a cemetery. The family is living in a two-bedroom basement apartment with more than a dozen other Venezuelans. They have also applied to enter the United States through CBP One and are waiting for their number to be called. They could try hopping the dangerous train known as la bestia to the border, where they could cross illegally. But for now, Bergkan can’t stomach a single additional risk.

When someone dies in the jungle, their remains are usually eaten by animals or swept away by a river, or they disintegrate in the hot, wet terrain. But sometimes a body is retrieved. Panamanian authorities have offered conflicting accounts of the number of bodies recovered from the jungle—ranging from 30 to 70 a year. But these appear to be significant undercounts. In one remote community called El Real, Luis Antonio Moreno, a local doctor, told me that a mass grave dug in 2021 had quickly filled with hundreds of migrant bodies—double if not triple the reported numbers.At a recent burial ceremony, municipal workers wearing hazmat suits placed 12 white body bags into graves. Ten of the bags were labeled desconocido, or “unknown.”

Moreno has operated El Real’s run-down hospital for 18 years. Its morgue is one of several in the area where bodies are taken after they are removed from the jungle. Moreno said he has processed the remains of people “from every country and every age.” Some arrive with their identification documents still protected in plastic baggies they had been carrying with them. Others are just bones. He teared up recalling two cases from last year: One was a father and son who drowned together; their bodies were still hugging when they were delivered to him. The other was a father and son who had both been shot in the head.

The morgue is next to the hospital kitchen. Moreno said the stench was often intolerable, even before the day this spring when he discovered that the air conditioner had gone out and the bodies inside were decomposing. In March 2023, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which has a program to help families track down loved ones who have gone missing while migrating, built a mausoleum in the local cemetery with space for hundreds of bodies, and it’s quickly filling.

At a recent burial ceremony, municipal workers wearing hazmat suits placed 12 white body bags into graves. Ten of the bags were labeled desconocido, or “unknown.” One bore the name of a man from Venezuela whose family had confirmed his identity. Just before the last body bag, which was also the smallest, went into the mausoleum, an ICRC worker opened it and placed a dog tag on the wrist of the 8-month-old Haitian girl inside.

After leaving panama, I sent a message to the phone number I saw on the flyer for the missing 9-year-old boy in Bajo Chiquito. The number led me to Bé Thị Lê, the mother of the boy, whose name was Khánh.

A single mother, Bé had worked in school administration in Vietnam, but lost her job at the beginning of the pandemic. She started watching videos that smugglers posted on YouTube of the trip through the Darién Gap; the journey seemed doable. Several relatives who had already migrated to the United States sent her money to join them. Bé and Khánh traveled for nearly a month to get to the jungle, flying first to Taiwan, then France, then Brazil, and then taking buses and cars through Peru and Ecuador to reach northern Colombia.

Bé sent me photographs and videos she’d taken of her son throughout the journey, posing on boats and at transit stations. In one video, Khánh sat on a hotel-room bed, using the Duolingo app to work on his English. He was practicing the phrase Yes, coffee with milk please, nailing all but the final word. The app prompted him to repeat it again and again: please, please, please.

In the jungle, they moved slowly and quickly ran out of food. On the fifth day, they walked into a river identical to dozens they’d already crossed. Neither knew how to swim, so they linked arms with an Ecuadorian man named Juan. The rain that had been pounding all day started to come down harder, and the water suddenly changed from clear to brown, signaling a flash flood. “The water was only up to my knees, but two steps later, it was up to my neck,” Bé told me. All three were knocked off their feet. Bé grabbed onto a boulder. Juan tried to do the same, but his backpack filled with water and pulled him under. Khánh slipped out of his grip. Juan and Bé scrambled to a patch of beach and looked out in the direction where the current had taken Khánh. He was gone.

Bé said she felt all the energy drain from her body as she sat on the beach, speechless and unmovable. Some of the other migrants in their group told her they had heard Khánh call out “Mommy” as he was pulled away. They offered her their condolences and kept walking. Juan eventually persuaded her to continue on so that they could report what had happened and get help trying to find Khánh. A day and a half later, they climbed up the stairs to Bajo Chiquito.

Border-patrol officers used a translation app to take down Bé’s account. They advised her to continue on to the larger camp near the highway to make another report. She did so, then asked her brother, who lives in Boston, to fly down and help her. Together, they returned to Bajo Chiquito and posted the signs that I later found. She said that officials there gave no indication that they planned to look for Khánh, and told her that she didn’t have permission to do so herself. At her brother’s urging, Bé turned herself over to American immigration authorities to request asylum, and then traveled to Boston, where she has been working in a nail salon. “My son has always been with me, since he was born until now. I have no husband, so there are times when I am not quite there,” she told me. “Not so conscious, not quite there. I’m physically still here, but emotionally not, because I miss him.”

Without a body to mourn, she’s become obsessed with the idea that Khánh may have been pulled out of the river or washed ashore. She thinks he may have been kidnapped by someone in the jungle, or perhaps he’s being taken care of but was injured or can’t remember her phone number. She thinks he might still be waiting for her to come get him. After I wrote to her, she sent me pleading messages almost every day for weeks. “Please help me find my son.”

When I contacted a representative at the ICRC about Khánh, the organization added him to the list of missing migrants it is trying to find. Months later, there has been no news. Bé continues to write to me. “What do you believe about my son?” she asked recently. “I’m always waiting for news of my baby.”

This article appears in the September 2024 print edition with the headline “Seventy Miles in the Darién Gap.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Caitlin Dickerson is a staff writer at The Atlantic. She received the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting.

. . .

Issue of the Week: Human Rights, Economic Opportunity, Hunger, Disease

Published December 30, 2023

As 2023 comes to an end, we focus on the issue in the news that may well determine the future of democracy and human rights in the US and the world at large.

The migrant crisis at the US southern border.

It involves not only the countries of Latin America, but nations in crisis around the world.

On Christmas Eve, Planet Earth Foundation’s Founder Keith Blume and Volunteer Project Director Clara Lippert jumped on a plane last minute to El Paso, Texas, next to Juarez, Mexico, where the Bridge of the Americas (and others) link the US and Mexico. It has been a primary point at which migrants have crossed the Rio Grande, by the thousands a day, into the US.

It seemed like the right place to spend Christmas.

We’ll go out on a limb and say we think there’s a good chance we were the only people on the planet to fly in as non-profit journalists on Christmas Eve to focus on this issue.

Every day before, for weeks, it was at the top of the world news, and especially in the US. But the global impact was and is at the top of the news for good reason. In addition to potentially being decisive in the US presidential election, the importance of the US to unique global events is tied to it in numerous ways. Most recently, Republicans in the US Congress have refused to extend aid to Ukraine (at a critical moment of an existential struggle in the war against Russian aggression) and Israel (and the leverage for, among other things, a two state solution for Israel and Palestine the US is pushing for), unless there is agreement on dealing with the border crisis and the immigration issue writ large. Shockingly, with issues involved that most agreed were critical, the Congress did not reach an agreement before leaving for Christmas break. Many think that it will after the first of the year, but it’s no sure thing. The politics are running the show.

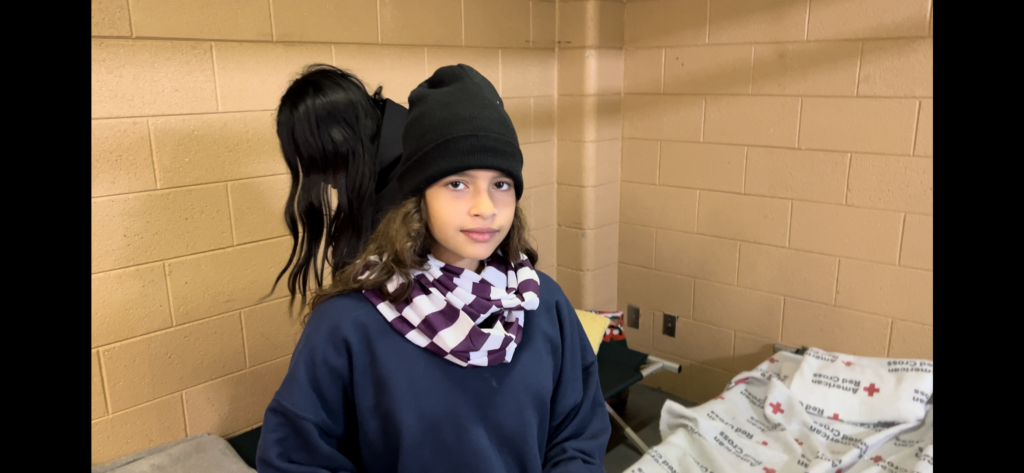

What we saw and heard in El Paso was stunning, even though we already knew all about it. Nothing like experience.

We’ve been writing for years about how migrant crises around the world have been bringing the world to the brink. And it’s all about one thing–people fleeing war, hunger, poverty, persecution–and struggling to survive and make a better life for their children, loved ones and themselves. So you walk though the jungle and next to cliffs and fall off and lose limbs or die, or get raped, or attacked by animals, suffer extreme hunger and dehydration–looking at the dead bodies as you keep going if you survive. You do this, and then take buses and trains in unsafe ways through unsafe places just to get the possibility of survival in the US.

How to deal with the situation is a complex question that is going to require compromise to begin with to accomplish anything–and this is going to outrage people on the right and the left. The specifics on this will be explored further by us. But suffice it to say what you know we will–nothing will solve this or any other of the crises on the planet without basic needs and basic rights being provided to everyone.

Recent talk about migrants poisoning the blood of other Americans from former president and now candidate for president again, Trump, after his defeat in 2020, is as putrid as could be. It’s straight up Nazi ideolocal ranting that most of us never thought would be possible in the US. There are nations in Europe which suffered through World War Two where you can’t legally do this–for obvious good reason.

But it’s also beyond absurd. Everyone in America, and the world, is and has been mixing blood for a long time.

A conservative Republican who runs a shelter in El Paso told us that his position as a conservative is that apart from the moral reasons to care for those in need, migrants are the lifeblood of the nation, pun intended. We need them, he said, to fill needed jobs and to support and grow the economy as has always been the case throughout US history. They’re not taking jobs from others, they’re helping to create more. And be clear what he said about why the huge majority of migrants are here–to work. They want nothing else. Just to work.

We heard the same thing from every single migrant we talked with. Work was the watchword. There’s no confusion about the truth when spoken by people who have been through more than most people could ever imagine to get here.

We shot hours of film, with Keith interviewing in English (and at times being second camera) and Clara interviewing in Spanish, translating, and doing the primary filming and photography. We intend to keep following the story during the coming year, which will start the “official” 2024 election campaign when the new year is here in a day, eventually producing a documentary on the issue.

We end the post, and the year, with photos from Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, on the border. And a short excerpt from videos on Christmas Day.

. . .

Published June 21, 2018

The End Of Civilization As We Knew It, Part One.

Today is the summer solstice in the northern hemisphere and the winter solstice in the southern. The great movement and balance of nature goes on.

But will it go on?

Before we go on, a note.

Over the years, in the previous system of the site (still in transition) for the Issue of the Week and Message of the Day, links in the text were not an option. One or two key links were provided at the end of the posts. This became purposeful, as troglodyte as it may have appeared. Activism on the internet, which we were part of pioneering, evolved, or devolved, with the internet itself. That is going to be a subject focused on more itself in the future. But for now, keep in mind that it was purposeful for us to require the reader to read, not jump around with links. It’s understandable that in view of getting an audience, most have used every new gimmick the internet has to offer. But studies have proven the downside of this, and many internet pioneers now decry their own creation.

Twitter, for instance, has now been made infamous. We understand why many use it and see it as needed. Just as we see it as the fact of what it is—the shrinking capacity, reinforced by the very use of it, to focus on more than a few characters—making, as we’ve previously noted, the 30 second TV spot seem like reading volumes. The 30 second TV ad that was the metaphor yesterday for the shrinking capacity and willingness of the species to think longer than that.

One of the things we did in our national and international public service campaigns was to reintroduce what even the corporate advertising world had ditched—the 60 second spot. They are like mini-movies compared to the 30s. And we received the top awards in the world for it. But more importantly, people watched. Feed crap and crap becomes demanded. Feed something better and the heart, mind and soul embrace it, if not immediately, then in time.

We do now provide some links in our commentary. But sometimes we will not, by choice. This is one of those times.

Now to the commentary.

We suppose that as good a moment as any, perhaps most appropriate among many, to locate in time the seemingly impossible to imagine change that has occurred in the recent history of civilization, would be the start of 2016.

And the place might be argued to be the UK, soon to explode further in the US and beyond. Hence our harking back to one of our travels to London, at the very start of that year.

Six months later, two days from now, two years ago, the stunning Brexit vote in the UK was a civilization-crushing milestone and a precursor for what at that point was concerning, but still a seeming impossibility in the US.

Of course, when referring to civilization in this sense, it’s Western civilization we refer to as a focal point. The rest of the world would understandably say—that’s when you were about to get it.

Nonetheless, it’s also true that Western civilization has had and does have a weighted influence on everything. Economic and military power, mobile phones and media and on and on and on. The struggle for power among the powerful is global and changing, and not.

Keep your eye on the ball.

Everything hinges on the gluttony of power versus economic equality and universal human rights. The locations matter only in their impact in determining the outcome of this struggle—and in that sense the locations can matter a lot. Although that proposition, in terms of the best Western civilization has had to offer, is precisely what has come into question more than ever as a result of events in 2016 and since.

As we keep saying, which is simply observing the most rudimentary facts of nature, the outcome of the historic struggle between justice, equality and sustainability or the gluttony of greed will be global and only global. It’s different than ever before because national boundaries are an illusion that are obliterated by dollars, and digital technology, and starving and desperate billions of people, and increasing billions of people period, and wars, and disease, and environmental crises, and the capacity to blow everything up on earth in a second for the first time in history–co-mingled realities only decades old after millions of years on planet earth, with growing interdependent force.

Who knew, on January 1, 2016, what was coming?

We all should have.

The co-founders of World Campaign were in London, perched on the Thames watching the fireworks as the clock struck midnight, January 1, 2016. Across the river, was a sight to inspire then, and to be branded on our souls in ways unimagined since. Here’s an excerpt from our first post of 2016, about photos of the year from CNN:

“The first picture is worth noting. It is the well-known image of Big Ben with incomparable fireworks exploding around it–and Westminster Abbey, Parliament, the Eye and all the famous sites around the Thames in central London. Countless thousands celebrated in what was the best place on the globe to be as New Years’s Eve turned to 2016–as it was completely dedicated to one theme, projected in blue on surrounding buildings–a benefit for UNICEF and the children of Syria in particular. But more broadly, the theme was a reminder of the top priority on earth:

HELP KEEP CHILDREN SAFE.”

All children. Everything rests on that.

But the particular focus on the children of Syria, should, in hindsight, be for all of us a moment like the scene from the 1956 movie “The Ten Commandments” when, as the commandments are being delivered to Moses on Mount Sinai, “Thou Shall Not Kill” comes crashing into his face exploding with soul-shattering personal guilt.

And, like all those in the camp below worshipping the false god of a golden calf, the powers that be and all of us had been and were willing to sacrifice the Syrian children to our own many false gods of greed, narcissism, denial, delusion, addiction to everything, fear, one-dimensional ideological reactions of all shades, unwillingness to act—not even recognizing our true self-interest in the midst of avoidance by even those who were partially awake, in response to nothing but horrible choices facing us, morality aside.

In the Book of Exodus (second book of the Torah and the bible) “The Ten Commandments” was based on, the consequence was 40 years in the desert.

We might wish for such an outcome compared to what has happened and what is-at risk of happening.

You can draw a direct line from Syria to Brexit to European disorder to Trump to the breakdown of the international order since World War Two, and the further initial promise in 1989, at the end of the Cold War, of that order becoming universal in democratic and human rights and so on.

But in that January of 2016 in London, all seemed well, all things considered.

Parliament actually debated the issue while we were there, on Janaury 18th, of whether to allow Trump, considered at best a cartoon candidate from another galaxy, to come to the UK. He had announced his campaign for president six months before, and from his first words, he appeared universally detested and sure to be politically destroyed by anyone in his own adopted party, much less by the first woman president in-waiting.

And the Brexit vote which all knew was coming, the June date announced during our next trip to London in February, seemed a clear political ploy by Prime Minister David Cameron, who hardly seemed to need it after the recent surprise election victory of his conservatives, which took him from a coalition leader to a formidable new force. The Brexit vote appeared a classic easy play to further his political power. Fine, welcome to all politicians. (Yes, he had said he would negotiate to reform the EU relationship and then have a vote to approve it well before his 2015 election victory—but he had the options of revising positions in a number of ways at various points as all polticians do, esepcially after the strength of his election win.) He was exceedingly popular at the moment, and it seemed unthinkable that his position would not be overwhelmingly supported regardless. The idea of Brexit would have seemed a rejection of the post-World War Two order that the UK helped form. To prevent such war again. To move forward in mutual self-interest of the UK and all the nations of Europe. To move forward in creating the global community as envisioned by the allies in the fight against fascism outlined in The Atlantic Charter. The UK and all of Europe were so interlocked at this point that the alternative seemed fantastical, and suicidal.

So not to worry, we thought, as we took a break from work at the Princess Diana memorial in Hyde Park (a simple, elegant, natural, beautiful work of art and flowing water.) The extreme lunacies in the UK and US would be trounced, and serve all the better to underline the need for global unity and to focus on the fights needed to make that a project of full equality at last. It was wonderful to walk and sit and talk of what could be accomplished on that cold clear winter day.

But on reflection.

2015, in fact, had been a year of catastrophic warning. Here’s an excerpt from our second post in 2016, about photos of the year in The New York Times:

“One more look at pictures from 2015, from The New York Times. The introduction follows:

THIS was the year of the great unraveling, with international orders and borders challenged or broken, with thousands of deaths, vast flows of migrants and terrorist attacks on some of the most cherished symbols of civilization, both Western and Muslim.

Palmyra and Paris (twice). Aleppo, Homs, Kobani and even San Bernardino, Calif. The Syrian war grinds on, half the prewar population displaced or gone, and the Islamic State fills a vacuum created by sectarian struggle and Western fatigue.

The conflict spurred the migrants lapping against the shores of bourgeois Europe, a million or more, huddled in small boats or crammed into airless trucks, abused by human traffickers, thousands dead on the journey, prompting both empathy and backlash.

Just look. The year is here.

The outrages of Boko Haram and the Shabab in Africa. The abuse of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar. The war in Ukraine and the resurgence of the Taliban in Afghanistan. New tensions in the skies over the Baltics and a Russian plane shot down by a NATO country for the first time in decades.

The ruins still in Gaza, a year after a brutal and inconclusive war, and Israel hunkering down in a region losing its compass. Even the energetic secretary of state, John Kerry, has given up on serious negotiations for Mideast peace.

So much uncertainty, anxiety, anomie, so many civilian victims: A crazed German pilot flew his plane into the French Alps; a Russian plane was destroyed over Sinai by what seemed to have been a bomb; attackers with automatic weapons killed 130 people in Paris in restaurants, a stadium and a concert hall.

Even the Earth seemed slightly unhinged ‘ the ice caps melting, sheep stuck in the smog of Beijing, huge snowstorms and floods, a major earthquake in Nepal, one of the world’s poorest countries.

And in the United States, it was a year of anger and protest against police brutality, with racial unrest ripping apart Baltimore and Ferguson, Mo. A massacre of black worshipers in a church in Charleston, S.C. Drought and terror in California, blows to the myth of paradise.

Presidential politics took on a carnival atmosphere during the pre-primary season, with an amazing cast of would-be successors to a grayer, grumpier Barack Obama. Bernie Sanders, the sort-of socialist from Vermont by way of Brooklyn, was giving Hillary Clinton a run, at least, for her mounds of campaign money. Donald J. Trump thrilled, amused and horrified, depending on your point of view, with his populist fulminations, his hairdo and his narcissism.

But not all of the memorable events of the year were about loss, violence and terrorism.

The changing climate brought a historic if relatively toothless deal to cut carbon emissions and help the poorest countries cope.

The massacre in Charleston helped lower the Confederate flag over the South Carolina State House. The Supreme Court made same-sex marriages legal throughout the land.

The United States and the United Nations Security Council finally reached a deal to limit Iran’s nuclear ambitions, promising some sanctions relief and opening a still-uncertain path toward a Syrian settlement.

In another resolution of a longstanding diplomatic sore, the United States recognized Cuba. And Myanmar’s military government seemed at last to recognize the political victory of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who stuck to her principles through decades of house arrest.”

Even many of the good parts noted at the end turned bad as we look back.

And the unmentioned speaks louder than anything. The virtually never headlined. How were the Syrian children and children everywhere and people everywhere doing in general before or without the above disasters?

After decades of progress, billions hungry, sick, homeless, stateless. Terror and war rising. In the US and UK, economic inequality rising, and rising and rising. Important human rights gains overshadowed by a dying middle class and increasing underclass. And where poverty was reduced, it also remained and grew, and the price of more prosperity for more people in some places was and is an increasingly unsustainable wasteland in more ways than one.

No one thinks population can continue its extraordinary sudden exponential growth over the past century after all of human history. No one thinks that the planet and its resources can magically expand beyond finite. The predicted population bomb was defused in part due to expanded prosperity for many. The arrogance of thinking it will level off because of a trend, with inequality on the rise again and with unsustainable economic models that are suffocating the planet, will lead to the only other way it will more than level off—global catastrophes threatening us all—making the thus far false prophecy of Malthus come true, and more, by our own doing.

For the first time in history, an architecture of technology has been created in which a Brave New World soma of control turns the most far-fetched science fiction into reality with the controllers themselves increasingly out of control or not capable of knowing what the architecture is becoming.

HIV-AIDS and other pandemics taking millions of lives and then seemingly, hopefully, maybe, coming under control (for those who can afford it or who are recipients of an always-at-resource-deprivation-risk system of assistance) that are precursors of global pandemics to come unprepared for.

Space to the rescue as the late Stephen Hawking mused? And a growing list of tech moguls. And to some extent, NASA. Exploration? Good. But full-scale space, Mars and other such migrations would at best look something like The Expanse—a corny and brilliant by turn SYFY television series, with the UN (the hub of government), Earth, Mars, and the underclass of workers strung out between. All engaged in competition and class and identity and power struggle with the good, the bad and the ugly. A real possibility. Which demonstrates why it needs to get worked-out here on earth first.

A billion children abused.

A handful of people and corporations with more money than half the planet.

Inconceivable.

The progress of globalism commandeered by the greedy and powerful, not just individually, but more importantly systemically and politically. And a culture of meaninglessness on a good day, leaving more and more disenfranchised in every sense.

What the hell did we think was going to happen?

We remind again, momentarily, of an excerpt from our post on the 100thanniversary of the Russian Revolution in October last year—quotes from Ian Frazier in his Smithsonian semi-book length masterwork, “Whatever happened to the Russian Revolution?”. His mesmerizing tale from the hope, to the horror, to the hope at the end of the Cold War, back to the past in a Soviet-Czarist hybrid with Putin, is worth reading until memorized.

But first a reminder on a related issue. The February Revolution, the real revolution hijacked in October by the Bolsheviks (who came to be known as the communists, who called themselves socialists, but who committed sacrilege against both terms in their anti-democratic dictatorship of lies and slaughter), started with the women of Russia. In the streets. Demanding bread. Not backing down. This was the day that became International Women’s Day, which most women in the West who celebrate the day have no idea about. As Gloria Jean Watkins, better known as bell hooks, has said, in so many words, about the white women in the comfortable developed world (and even those of color to some extent in the same comfortable condition)—their feminism often misses the point of the global need for a feminism to end the hunger and poverty and powerlessness of the majority of the victims of sexism and racism and homophobia and classism, all inequalities, in the world. The Russian women in the streets a hundred years ago were women who got it, and who demonstrated the lie of sexism, of the weaker sex, by fearlessly leading the revolution themselves.

As we’ve noted before, had the democratic socialist revolution that occurred almost instantly taken root and been adhered to, it would be a very different world since.

Now to the quote from Frazier:

“Problems left unsolved take their own course. The river in flood cuts an oxbow, the overfull dam gives way. The Russian Revolution started as a network of cracks that suddenly broke open in a massive rush. Drastic Russian failures had been mounting—the question of how to divide the land among the people who worked it, the inadequacy of a clumsy autocracy to deal with a fast-growing industrial society, the wretched conditions of hundreds of thousands of rural-born workers who had packed into bad housing in Petrograd and other industrial cities, to name a few. But nobody predicted the shape that the cataclysm would take.

The speed and strength of the revolution that began in February of 1917 surprised even the Bolsheviks, and they hurried to batten onto its power before it ran away from them. An early sense of unexpectedness and improvisation gave the February Revolution its joyful spirit. Russians had always acted communally, perhaps because everybody had to work together to make the most of the short Russian growing season. This cultural tendency produced little soviets in the factories and barracks, which came together in a big Soviet in Petrograd; and suddenly The People, stomped-down for centuries, emerged as a living entity.

One simple lesson of the revolution might be that if a situation looks as if it can’t go on, it won’t. Imbalance seeks balance. By this logic, climate change will likely continue along the path it seems headed for. And a world in which the richest eight people control as much wealth as 3.6 billion of their global co- inhabitants (half the human race) will probably see a readjustment. The populist movements now gaining momentum around the world, however localized or distinct, may signal a beginning of a bigger process.”

Many people, especially in the West, remain asleep as to the extent of the change underway. The more comfortable, the more so, while the majority struggling have no time to pay attention, except to the extent they lash out, fight back, with varying degrees of consciousness.

The river in flood cuts an oxbow, the overfull dam gives way.

When the dam breaks, it knows no left or right or middle or rich or poor or race or gender and so on. It just drowns us all.

So, let’s go back for a moment to another point in time when the current great unravelling could be traced to.

On January 30th this year we reminded:

“Today is the 136th anniversary of the birthday of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

We have examined his unique positive role in the history of the US and the world often. And we have pulled no punches on his grievous failures.

But he is without question one of the three great US Presidents with Washington and Lincoln. And in the world we know today, with all its risks and opportunities, his role was and is unique.

He forged The Atlantic Charter and the United Nations post-war world in the summer of 1941 before the US was in the war and before most Americans wanted to be. He defined the anti-facsist struggle as one that must end in a world of “equality of peoples.”

Five months before the D-Day landings at Normandy, he outlined to the American people what this new world would mean for them–and for the world–a second bill of rights. Basic needs for all must be a basic right, and are the basic requirement for a stable world of peace.”

Last week we revisited the post last year of the 40th anniversary of the White House document from June 11, 1977, that may have been the last meaningful policy statement of this grand vision that could have happened before the great unravelling began. The unraveling was a process, unreocginized for some time in many ways because of the enormous progress being made simultaneously and because of the weapons of mass distraction working with increasing effectiveness. History doesn’t stop or start at any given moment. Focal points, such as 2016, are milestones, from which we look both backwards and forwards. We will visit further why, as history since has shown, this document and moment had the historical meaning they did.

Here’s an excerpt from the White House document in last week’s post:

“We can establish broad but practical and measurable human needs goals, e.g., programs of food production and basic nutrition, development of low-cost health delivery systems, adequate maternal and child health programs, rural sanitary water supply development, humanitarian food trade policies, etc. Importantly, this must be done on a government-wide basis to ensure consistency and comprehensiveness. Implementation would then follow through the development of a comprehensive global plan, including goals for the basic human needs of life: adequate and quality food for everyone, basic health care, education, jobs.”

A comprehensive global plan, including goals for the basic human needs of life: adequate and quality food for everyone, basic health care, education, jobs.

Imagine that world.

There’s nothing idealistic about it. It’s the reality that will happen sooner than you think, if we are to survive. The proof on why it has to happen, how it has been modelled large scale in various ways, incomplete because in the end it always would be until applied globally, should be self-evident by now. But this reflection will continue with more specifics on that.

The biggest question, if we survive to get there, is the cost of our denial.

The river in flood cuts an oxbow, the overfull dam gives way.

. . .

To be continued.

- “Landmark moment as Dame Sarah Mullally to become first female Archbishop of Canterbury”, The Independent

- “Believe Your Eyes”, The Atlantic

- Issue of the Week: Human Rights

- “Brooks and Capehart on Trump forcing allies to reevaluate ties with U.S.”, PBS NewsHour

- Issue of the Week: Human Rights, Economic Opportunity, War, Hunger, Disease

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017