Issue of the Week: Disease, Population, Human Rights, Personal Growth

The Scars of Bergamo Five Years after COVID, Der Spiegel, 21.03.2025, Illustration: Julian Rentzsch

Today is the first day of Spring in the Northern Hemisphere, the first day of Fall in the South.

Halfway between light and dark, the longest and shortest days of the year in both cases.

A metaphor perhaps for where we are about Covid and what happened in the pandemic and the continuing impact of it, which can’t be overstated and is still in process. Many of the most critical things in history are happening and at stake as we write. But we can’t let the Covid story, five years since inception this month as we pointed out in our last post, out of our site. It’s affecting everything and all of us physically, psychologically and socially as nothing before it because of the modern context in which it occurred, and without full attention on the issues around the risks of global pandemics that exist more than ever, we could risk extinction.

So we spend another week on the issue, this time in the extraordinary article today in Der Spiegel (March 20 in our time zone, March 21 in Der Speigels’) from the European perspective.

Here it is:

The Scars of Bergamo Five Years after COVID, Der Spiegel, Berlin, 21.03.2025

By Francesco Collini und Katrin Kuntz in Bergamo, Italy; Photos by Elisabetta Zavoli

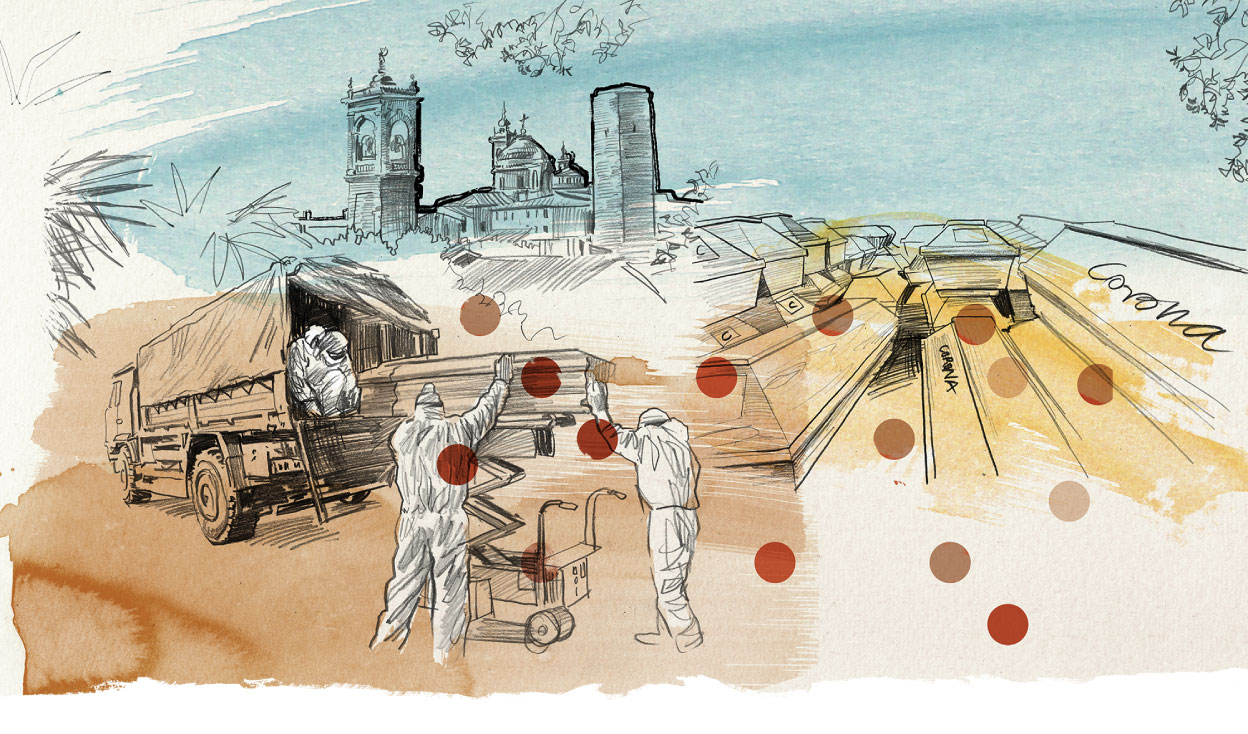

The images that began coming out of Bergamo in early 2020 – of coffins being loaded onto military trucks as the coronavirus tightened its grip – spread fear across Europe. And the scars are still fresh today.

Brother Marco Bergamelli still remembers exactly when the photo was created that would jolt Europe out of its ennui. During a walk through the central cemetery of Bergamo, he stops at the entrance: “They were parked here: one, two, three, four, five … 10 trucks, all backed up,” says the clergyman, raising his arms to the sky.

The military trucks pulled up here 12 times during the first COVID-19 wave, taking away up to seven coffins each, loaded up by soldiers wearing plastic hazmat suits. The central cemetery simply wasn’t able to keep up with the cremation demands and the army vehicles were needed to bring dozens of dead bodies to crematoria in other parts of the country. On March 18, 2020, alone, there were 73 of them. “Initially, they would drive at night, in the darkness after 8 p.m. Nobody was supposed to find out how large this pandemic really was,” says Brother Marco.

But one local filmed the scene with his mobile phone. And a still from that video became the photo that revealed to the world that Bergamo was a corona hotspot.

A city at war against an invisible enemy.

Brother Marco Bergamelli in the chapel of the central cemetery of Bergamo. “I prayed back then: Please, give us at least a spark of health.” Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

Brother Marco, a 70-year-old Capuchin monk, is a frugal man with a biting sense of humor. And that year when the coronavirus arrived, he was one of the city’s leading crisis managers. He had been working at the central cemetery for more than 10 years by then, reading mass, hearing confessions and conducting funerals. In the first two months of the pandemic, the province of Bergamo, with a population of around a million people, lost more than 6,000 people to COVID-19. As a central collection point for the dead, Bergamo’s central cemetery, the Cimitero Monumentale became an epicenter of the pandemic.

Nowhere in Europe did the virus claim as many lives at the beginning of the pandemic as it did here. And the region quickly became a symbol for the arrival of the virus in Europe – and for the fact that the European continent was no better protected than anywhere else in the world. The events in Italy also triggered fears in Germany of being overwhelmed by the disease. In the political debate, “the images from Bergamo” quickly became shorthand justification for restrictive measures to combat the spread of the virus.

What marks did the crisis leave behind at this place? And what about the people whose family members were laid to rest here?

The Cimitero Monumentale, surrounded by walls, measures 177,000 square meters and is the final resting place of around 190,000 people. There are imposing family graves decorated with elegant sculptures, 346 private chapels and an area marked with colorful windmills in the western part of the cemetery for children. Another area, filled with modest graves, is reserved for nuns. Benches and the occasional solitary cypress can be found where the paths intersect. On the east side of the grounds are fields for those who died in the resistance against Hitler and Mussolini and right at the edge is a crematorium that whistles loudly when in operation.

Brother Marco has thrown a winter jacket over his brown robe. From the entrance of the cemetery, he turns left to Campo B1, where 129 graves are packed closely together, all of them belonging to people who died in Bergamo during the coronavirus period. An additional 684 victims of that first corona wave between mid-February and late-May 2020, have been laid to rest elsewhere in the cemetery.

Brother Marco steps up to a man wearing a stocking cap and holding a watering can in front of a grave. He lays a comforting hand on his shoulder and says a few words about corona and about the fact that people on social media have begun voicing doubts as to whether the military trucks really were full of coffins back then. The man starts swearing.

MARIA ROTA

† APRIL 10, 2020

“I don’t want to curse at a cemetery,” Giuseppe Mortellaro says. “Say it, say it!” Brother Marco says in encouragement. A friendly 63-year-old with deep wrinkles around his eyes, Mortellaro doesn’t look like someone who frequently loses his temper. But he is furious with those people who deny the existence of the virus.

“If I had one of them in front of me, I’d probably end up in jail,” he says.

Mortellaro is standing in front of parcel 159 in the first row of B1, the grave of his mother, Maria Rota. Her resting place is covered by a simple slab of marble; the photo on the gravestone shows a woman with shimmering hair surrounding a resolute face.

The graves of those buried in Campo B1 are all crowded next to each other, as are the dates when they died: March 2020, April 2020, May 2020. Most of them were senior citizens when they died.

As was Maria Rota. She was 88 years old when she died in a retirement home on April 10, 2020. Mortellaro says she was a strict mother – that if he didn’t obey the rules as a child, she would reach for the carpet beater. And Rota also had difficult relationships with her relatives, he says. “She would turn little things that rubbed her the wrong way into huge problems,” he says. But she still loved being around others and, he says, she “gave everything” to her grandchildren. Her niece placed a small sculpture on the gr

“I was lucky that I was able to visit her in the retirement home the day before her death. I had to wear white overalls over top of green ones, along with a mask and two pairs of plastic gloves. I looked like a monster. I stroked her forehead, but she was already fast asleep. I got the call that she had died at around 5 a.m. the next morning.”

The family had just a few hours to arrange her funeral, Mortellaro says.

“Only at the cemetery did I understand what was happening. B1 looked like a battlefield. Piles of dirt everywhere, along with freshly laid flowers. We had 20 minutes. The two prayers we were allowed to recite lasted for about five minutes. We didn’t even have time to throw a flower into the grave.”

Retiree Giuseppe Mortellaro at the central cemetery of Bergamo: “We didn’t even have time to throw a flower into the grave.” Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

Mortellaro’s story is similar to those told by many in Bergamo: one of sudden loss and unprocessed trauma.

The first corona patient in northern Italy was diagnosed on February 20, 2020, in Codogno, just southeast of Milan. A short time later, Rome ordered a complete lockdown in the town and the surrounding communities. Three days later, on February 23, doctors localized two cases of SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital in Alzano Lombardo in the beautiful Seriana Valley, just a few kilometers northeast of Bergamo. The clinic, filled to capacity at the time, was reopened by the authorities just a few hours after it had been closed, a decision which turned the town into a superspreader for the surrounding area. It was the beginning of a series of miscues, which, in combination with local conditions – such as an aging population, lively trade with China and no shortage of air pollution due to its location in Italy’s industrial heartland – led to catastrophe.

Mortellaro says that he lost around 20 family members and acquaintances during the pandemic. He has been receiving psychological support since then and continues to take part in self-help groups for the bereaved. It is as if his spirit was unable to keep up with the speed of the pandemic.

Maria Rota’s gravestone is engraved with an orchid, her favorite flower, along with a sentence from St. Augustine: “What we were for each other, we still are.” Mortellaro wipes a few tears from his face. “Those who are remembered never die.” He then gently strokes his mother’s photo. Ciao, he whispers as he leaves.

Giuseppe Mortellaro at the grave of his mother Maria Rota: “Those who are remembered never die.” Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

During his stroll through the cemetery, Brother Marco repeatedly comes to a stop. “So many people experienced a loved one leaving home, convinced that they would return – but then they came back in an urn,” he says. Many family members weren’t even able to come to the cemetery, with the rules in Italy at the time requiring that contact persons remain in quarantine for 14 days. Some would simply wave at the hearse as it drove by.

Inside the church, they had to push the benches to the side. “We needed room for 600 caskets,” says Brother Marco. The dead had to be put somewhere before they were buried, and because the central cemetery could only handle 25 cremations per day at the most, the dead had to be quickly taken somewhere due to the danger of infection. “To Florence, Parma, Varese, Pordenone, Trento,” says Brother Marco. They would be cremated there, and their urns could then later be picked up at the Cimitero Monumentale.

CLAUDIO LONGHINI

† MARCH 19, 2020

Cristina Longhini, 43, parks her white Honda, which she inherited from her late father Claudio, outside the imposing cemetery gates. A self-confident woman wearing elegant boots, she has blond hair and wide, blue eyes that quickly fill with tears as she talks. She hasn’t been to her father’s grave for half a year, she says, because she was so busy caring for her younger sister, who just recently died of cancer.

Claudio Longhini’s ashes are in a columbarium located in a kind of cave. The vaulted ceiling is three meters high, and the space is filled with narrow compartments for the urns inside, each with a photo of the dead as is common practice in Italy. Longhini is smiling in his picture, his name written in red lettering, a vase of small plastic flowers next to it.

Cristina Longhini in the car she inherited from her late father Claudio: “I have lost orientation in my life since his passing.”Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

“The red symbolizes his zest for life. My father had a sunny disposition. He sold cones to ice cream parlors; his customers were his friends. He was a grandfather who loved his grandchildren and was also involved in the local basketball team. He rode a motorcycle. He loved the sea and could never sit still. He was very good at impersonating people. We spoke on the phone frequently, he called me ‘Chicchi.’ I have lost orientation in my life since his passing.”

Longhini orders a hot chocolate in a café near the cemetery. The server recognizes her as a pharmacist who makes frequent appearances on television. Earlier, she says, she had wanted to become a teacher. “But during corona, I fell in love with my job.” Like many of her colleagues, she received training during the pandemic in giving vaccinations and recalls being celebrated with applause. “Those entering our profession still only earn a net monthly salary of 1,369 euros,” she says.

She is no longer willing to accept the poor working conditions and has begun organizing protest marches. Talking about her father is an element of her activism.

“I realized on March 7 that my father wasn’t doing well because he didn’t wish me a happy birthday. A doctor diagnosed him with stomach flu. A few days later, he lost consciousness. Despite the chaos of those days, we were able to use social media to find a general practitioner who came to see him at home. My father’s oxygen level was just 65 percent. By March 12, it had already become difficult to find an ambulance, and the one for my father came from a different town. They put him in a wheelchair. He left his mobile phone and wedding ring at home for fear that they might be stolen. That was his biggest mistake. We never heard from him again.”

Claudio Longhini’s final resting place: “The red symbolizes his zest for life. My father had a sunny disposition.” Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

Cristina Longhini at the columbarium where the ashes of her father, Claudio, are interred: “It still hurts that I couldn’t hold his hand as he died.”Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

The public health system in Italy normally works quite well. But during the financial and economic crises beginning in 2008, the state, carrying an immense sovereign debt load, made significant cuts. The Health Ministry’s pandemic plan, for example, apparently hadn’t been updated since 2006 by the time the pandemic struck. And when the first coronavirus wave rolled over the country, doctors and hospitals were overwhelmed.

In the central hospital of Bergamo, doctors fitted her father with a ventilation helmet, Longhini says. But after learning that piece of news, she says, the family was unable to reach a doctor for an entire week, and a visit was out of the question. On March 18, the day when the photo of the army trucks began circling the globe, she learned that her father had been taken to the emergency room for a tracheotomy. The family was told they had to find an intensive care unit to bring him to. But before they could, Claudio Longhini died. He was 65.

On March 19, Italy reported 3,405 deaths, exceeding the toll in China for the first time – and more than any other country in the world. Italy’s top health institute said at the time that the average age of the dead was 79.5 years, with those between 80 and 89 hit hardest.

Cristina Loghini remembers speeding the 50 kilometers from Milan, where she lives, to Bergamo. At the hospital, she was handed her father’s personal effects in a garbage bag, including his pajama tops and a T-shirt covered in blood along with his glasses and health card. Cristina Longhini was shocked by the blood. “We were unaware of his suffering.”

The last time she saw her father was in the morgue.

“I entered an empty room; he was lying in a zippered shroud. Dad was very white, his eyes were still wide open and his nose was crusted with blood, probably from internal bleeding. I drove my car behind the hearse to the cemetery, but I couldn’t follow him any further than that. My father wanted to be cremated. The fact that he had been taken 216 kilometers to Ferrara for his cremation is something I only learned when I got the bill for 500 euros.”

Claudio Longhini’s funeral took place on April 18 and lasted 15 minutes.

“For a long time, I kept thinking that I would one day find my father sitting on the sofa again as he so often did. It still hurts that I was unable to find an intensive care unit and that I couldn’t hold his hand as he died.”

Shortly before Cristina Longhini got back into her car at the cemetery, she opened up the trunk. She has a box full of her father’s things that she still keeps: a CD, a business card, mouth, mouth spray. As a sales rep, she says, he had basically lived in this car.

EMILIO SQUINZI

† MARCH 22, 2020

A few hundred meters from Longhini’s grave, in the western part of the cemetery, there is another wall of graves. It is covered, but it opens out to a green field. Emilio Squinzi’s grave is in the top row. Those wishing to view his resting place straight on must make use of the wheeled ladder. A painted edelweiss adorns the plaque on his grave along with a photo of him hiking, his passion.

His son, Gianpietro Squinzi, talks about his father’s life at the table in his modestly furnished apartment just outside Bergamo and points to the empty chair to his left. That, he says, is where his father was sitting on March 1, 2020 – the last time the two of them shared a meal. Polenta with rabbit, a regional specialty that his father loved, but that day, he didn’t touch his food and his breathing was shallow. So Gianpietro took him to a doctor who then sent him to the hospital after a positive coronavirus test.

Gianpietro Squinzi in his apartment in Bergamo: Mourning mixed with anger. Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

Word was beginning to spread at the time that many people were suffering from respiratory illness and the first COVID-19 cases were being publicized. Nevertheless, regional business leaders were trying to play things down and the Bergamo employers’ association launched a campaign under the hashtag #bergamoisrunning to oppose factory closures. Nobody really understood just how dangerous this virus was. Nor did they realize that the situation was about to get far worse.

Squinzi remembers counting between 30 and 40 ambulances arriving during the four hours he waited in front of the clinic. Like many others in Bergamo, he can still hear the wailing of the sirens today. Because his father had fallen asleep after being admitted, he decided not to disturb him and drove home.

The Chinese mega-city of Wuhan, where the virus apparently got its start, had been under quarantine since January 23. By early March, the Chinese authorities had largely got the situation back under control with the help of draconian measures put in place to stop the spread of the virus. The fact that Bergamo would soon be known as the “Wuhan of the West” also had to do with the fact that infections began spreading uncontrollably in the region far earlier than in other parts of Europe. And no pattern had yet been established for how democracies would deal with the pandemic. Italy was the first country in the pandemic to ban flights from China. But people continued traveling into the country from China via places like Zurich and Frankfurt.

Squinzi says that he received regular phone calls from the hospital for 16 days, with the doctors assuring him that his father didn’t require intensive care. During this period, on March 9, 2020, Bergamo became a “red zone,” a lockdown area – at the same time as the lockdown was implemented for all of Italy. On March 16, Squinzi learned that his father had been transferred to a rehabilitation clinic in San Pellegrino Terme, some 25 kilometers north of Bergamo. “I thought he was doing better.”

On March 18, he received another call, telling him that his father had taken a turn for the worse. A doctor then asked Squinzi to arrange for an ambulance and a bed in intensive care. Squinzi says that he had already heard by then of plenty of others in the neighborhood who had made unsuccessful attempts, and he didn’t even try. The next day, he says, he drove to the clinic, but he wasn’t allowed to enter.

“My father was a bricklayer, widowed for 11 years. We would go climbing, skiing and visiting glaciers. We’d been going to the mountains since I was a child, to the Aosta Valley, to South Tyrol. Today, I think we would have succeeded in passing this test as well.”

Gianpietro Squinzi’s voice falters as he talks, anger mixed in with the sadness.

“On Sunday, March 22, I received the call that my father had died. They told me I needed to find an undertaker to pick up his body. I asked when and how he had died. And I asked if he had called for someone from the family during his final moments.”

He didn’t get any answers. Squinzi says he called all of the undertakers in Bergamo, but there was a 25-day waitlist. Because the cemetery was full, his father’s body was kept in San Pellegrino Terme for five days at a cost of 150 euros. When his father was then interned in the Cimitero Monumentale in Bergamo five days later, Squinzi wasn’t allowed to go to the grave due to the risk of infection. He never saw his father’s body.

Gianpietro Squinzi showing a photo of his father Emilio: “I am convinced that I will never be able to properly mourn.” Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

Emilio Squinzi’s grave: His photo shows him on a hike – his passion. Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

“I went to the cemetery with my brothers. It was quiet except for the freight elevator lowering the coffins. I was only able to visit his grave when the cemetery reopened in late May – and I found a stone without a name. It was like him dying a second time. They hadn’t even managed a mundane inscription. I went home, printed out a photo and a piece of paper with his name on it and attached it to the gravestone. It was the least I could do.”

According to a study carried out by the Italian statistical office, there were almost six times as many deaths in the province of Bergamo between February 20 and March 31 as there had been during that same time period one year earlier. The mistakes that were made during this time of intense strain have left behind scars on the psyches of many of those who lost loved ones.

Gianpietro Squinzi, Cristina Longhini and others have formed an association of the bereaved and are suing the state. Squinzi is convinced that his father was forced to give up his hospital bed to a younger patient.

Prosecutors in Bergamo conducted an investigation into negligent homicide against Italy’s then-prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, and the former health minister, Roberto Speranza, before suspending the investigation in 2023. Since last September, an investigative committee in Italian parliament has been looking into emergency management practices during the pandemic.

For a time, says Squinzi, he stopped hiking in the mountains. At some point, though, his friends pulled him out of bed to go on a hike.

“I am convinced that I will never be able to properly mourn,” he says. Too much has remained unresolved, he believes.

Back at the cemetery, Brother Marco stops at a family grave.

“We were performing 20, 30 burials per day back then. At the beginning, we didn’t even have masks. After several weeks, we received canisters full of disinfectant. We were afraid that the virus would seep out of the coffins and infect us. We would cover the outside of the coffins with those golden insulating blankets that are used for refugees at sea.”

ROSY SANNA CIAGÀ

† MARCH, 17, 2020

The ashes of Rosy Sanna Ciagà, who died at age 83, are to be spread at sea. For now, though, they are on a dresser high above the rooftops of Bergamo, next to a photo of a younger Rosy together with her husband. A weeping fig towers over the piece of furniture, with sunlight pouring in through the skylight.

Leyla Ciagà wanted to have her mother with her.

She is an only child and had a tight relationship with her mother. Ciagà, 59, is an architectural historian at the Polytechnic University of Milan and was a member of parliament during the administration of Mario Draghi – a svelte, elegant woman who has received her guest in her apartment.

Because she suffered from Alzheimer’s, Rosy Sanna Ciagà had been in a care home for a couple of years prior to the pandemic – and the home was closed to visitors in late February 2020. “I can’t even remember the day when I last saw her,” says Ciagà.

“First, they told me that I could no longer visit her. Then, they said she had pneumonia, but not COVID. One week later, she died. I asked why she hadn’t been taken to the hospital, and they told me that people who got sick in the care home were kept there because the hospitals were filled to overflowing. The worst thing was that I couldn’t be with her. She died alone.”

Leyla Ciagà in her apartment in Bergamo. “They told me that people who got sick in the care home were kept there because the hospitals were filled to overflowing.” Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

Leyla Ciagà showing an issue of the local Bergamo paper from March 2020: “Nobody told me that my mother would be loaded onto such a vehicle.” Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

Around half of those who died in Italy were from care homes and retirement homes, with the risk they faced having long been underestimated. Today, those cases are collectively known as the “strage dei nonni” – the massacre of the grandparents. Ciagà believes that her father, who died a few weeks before her mother, also succumbed to COVID, though he was never diagnosed with the virus.

Rosy Sanna Ciagà worked as a lab technician in a clinic and loved traveling. Her husband, a Turkish man from Istanbul, had come to Italy to study architecture at the Polytechnic University. “When they were young, they would go horseback riding, skiing and play tennis. There was a deep contrast between the way they lived their lives and how they ended.”

After her mother’s death, Leyla Ciagà went to the care home hoping to at least see the coffin before it was taken to the church cemetery. But Rosy Sanna Ciagà’s body had already been loaded onto a military truck – the existence of which Leyla Ciagà only learned from the newspaper.

“Nobody told me that my mother would be loaded onto such a vehicle. I was only able to pick up her ashes at the central cemetery several weeks later.”

At the central cemetery in Bergamo, Brother Marco returns to the church after his walk on this day in February, five years after the catastrophe. “I have always said that it wasn’t God who sent this virus. God is not vengeful; He doesn’t punish people. I prayed back then: Please, give us at least a spark of health.”

Leyla Ciagà sitting in front of a memorial for coronavirus victims near the main hospital of Bergamo. The ashes of her mother are to be spread at sea. Foto: Elisabetta Zavoli / DER SPIEGEL

Inside the church, Brother Marco sets up a metal bier in preparation for a funeral. A small group of mourners is waiting outside.

A man from Bergamo has died. Of old age. He was 101 years old.

- “Landmark moment as Dame Sarah Mullally to become first female Archbishop of Canterbury”, The Independent

- “Believe Your Eyes”, The Atlantic

- Issue of the Week: Human Rights

- “Brooks and Capehart on Trump forcing allies to reevaluate ties with U.S.”, PBS NewsHour

- Issue of the Week: Human Rights, Economic Opportunity, War, Hunger, Disease

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017