Issue of the Week: Human Rights, Economic Opportunity, War, Hunger, Disease

This coming weekend is the Martin Luther King, Jr. Day weekend in the US, culminating on the Day itself, Monday, January 19.

2026 is the 40th anniversary of its first observance. For many years this day was observed with seriousness, sacredness and focus. It was always, however, lacking in substantial and universal focus on the full scope of the core issues of social justice and social change King advocated.

Today, we live in a time when it’s just another three day weekend, the name having no other meaning.

It’s a time of shame more than any other in history, in many ways, in which the values of King and the universal values of all great and good people of all times are being denigrated culturally, socially, politically and personally.

Hannah Arendt’s phrase “the banality of evil” is one of many that come to mind.

This horrid moment in history too will pass, assuming life on earth survives it, and all the levels of shame will be remembered in infamy, always.

King is the only person in US history to have a holiday dedicated, other than US presidents. The Day recognizes his birthday.

He is, unquestionably, one of the most influential people to have ever lived. He was assassinated on April 4, 1968.

We have written often of him and his times and his values. Our honoring of him and his values on this 40th aniversary of this day will be to revisit his own words in the Letter from Birmingham Jail in 1963 and excerpts from The Three Evils of Society addresses in 1967.

First, a brief revisiting of some of our own observations, and some additional ones now.

Issue of the Week, 7.18.17:

Who does the US have national holidays for in their name?

One person.

Even Washington got morphed into President’s Day (Lincoln too as part of this, although he never had a federal holiday)–and how many now even know the origin of that?

Even Jesus, who has Christmas, isn’t the center in practice of the holiday of his birth in the US (and many other places.) The “Christ” in the holiday name would seem to be clear–but for separation of church and state reasons in the US, because the churches are less and less attended, and because the holiday was utterly taken over by consumerism driven by emotion- targeted advertising long ago, the name of the holiday is more an echo of its origin than not.

One person has a national holiday in the most powerful nation in the history of the world named after him.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

He didn’t necessarily deserve it more than some of his allies and contemporaries, not to mention those who came before. He treated women as sex objects at times at the further expense of his wife and family. He was sexist and homophobic with some of his closest allies who made the movement and made him possible in many ways. He also associated with the above at a level many didn’t at the time. And no one who was out front on the principles he was would have failed to move past the above limitations as the culture did after he died in no small part because of the principles he died for.

In any event, he’s got the holiday. The only one who does.

King identified racism, poverty and war as the three greatest evils the world faced. He was close to right.

But let’s just pick a couple of the most obvious missing issues to make the point.

Where’s sexism? Lost in his own patriarichal world. He sexually objectified women at best and did not give anything close to proper credit to women in the Civil Rights Movement, although he did so more than many. And homophobia? He never confronted this, yet he was as close as one could be to fellow civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, who was gay. And what about the most important issue, for the most vulnerable among us, the first responsibility of adults and the future of the species–the rights of the child? Child sexual abuse, violence and neglect face half the children on earth. Additionally, far more children than adults are harmed and die from every other evil on earth.

These issues are in part covered by the three issues King focuses on, but only in part. There’s no reason to avoid his shortcomings and every reason not to, as we pointed out years ago. Ironically and uncomfortably, the words of Jefferson, who owned slaves and never freed them, were a critical part of the evolution that supported the principles King stood for, just as his own evolution moving at rapid speed would doubtless have led him to the same place his words and actions were used for after his death to support the issues he didn’t focus on or fell short on in his lifetime.

Of the three evils he focused on:

Racism remains an abomination causing inequality, suffering and death everywhere, between different peoples of color at least as much as anything globally, and often the issues of hatred and inequality between same race or ethnicity is tribal or religious or whatever can be used to divide and conquer by the haves versus the have nots.

Which leads to the next focus of poverty, which his Poor People’s Campaign, the last great effort of his life, was dedicated to, inclusive of all races and all people equally, to provide jobs and guarantees for the basic needs in life for all people.

The lack of which feeds the last evil he focussed on. War, in a vicious cycle of causing and being caused by the deprivation of a majority of humanity in needs and rights. And which could destroy the world with nuclear weapons at any moment.

The context in which he spoke out was at the apex of the Vietnam War, which was tearing America apart, taking resources from needed social programs. He was not, however, opposed to war or force under any circumstances. Non-violence was an ideal and a strategy. But shortly before he died he made clear he would have taken up arms against Hitler. He certainly did not object to armed federal forces sent by President Kennedy and Attorney general Robert Kennedy, the brothers who saved the planet from nuclear destruction, to enforce the law of the land when it came to segregation. He opposed unnecessary and unjust violence.

King was a Baptist minister in the Black Church. In the movement he led and represented, King was a true Christian in his messaging. While denominations ranged from fundamentalist to liberal, it was the heyday, in no small part thanks to King, of Christian meaning following the words and actions of Jesus, which are omnipresent values in most religions and philosophies. It helped King get his message across at a time when Christianity was by far the most widespread, and most practiced, organized religion in America. King’s Christianity was the opposite of exclusive, or it’s Jesus’ way or the hellway–it was completely inclusive. “Follow me” meant what it means–do what I showed you in my actions. Usually, that was feed the hungry and take care of everyone’s needs. Sometimes it meant kicking over the tables of the merchants of greed, or telling anyone who would hurt a child to become a permanent anchor in the ocean first. For King the obvious message was that meaning in life is derived in being there for others. Then we’ve saved the world.

March 31, 1968 is best remembered as the day President Lyndon Johnson addressed the nation on TV in prime time, and shocked the world by announcing that he would not run for re-election. He was the architect of American involvement in the Vietnam War writ large. It had laid waste to his most extraordinary legacy in passing the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicare, Medicaid, the War on Poverty and so on. This path had been started by assasinated President John F. Kennedy (who gave a prime time TV speech for the ages on civil rights after being prodded by King for not doing enough) and brought to fruition by his vice-president, now President Johnson, who after becoming president after Kennedy’s death, had won election to his own first term by a landslide.

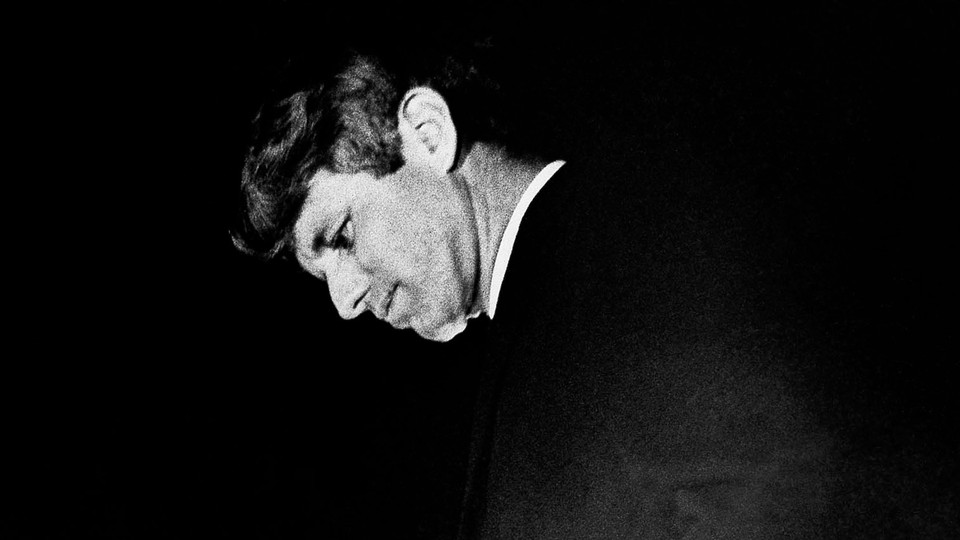

Now with that term coming to an end, he was being challenged for the Democratic nomination for president, most importantly by Kennedy’s brother, Robert F. Kennedy. Though his name has currently been in some ways usurped in public consciousness of those not alive at the time, and shamed by his apostate son, Jr., Bobby Kennedy was the most popular politician in America if not the world in 1968. His attacks on the policy of LBJ in Vietnam had been devastating. And LBJ seemed to genuinely be seeking peace talks with North Vietnam now, as the main reason LBJ gave for not running, so that not one minute of his time would be spent on partisan politics. It would not have helped him to do so in any event, but the war had broken him too, and the only redemption was in seeking peace. What transpired in lack of success, and what might have transpired if two bullets had never found their targets, is a topic covered before by us, and by many, and to be examined further another time.

Although he had no lack of understanding of the evil of totalitarian communism in North Vietnam, the Soviet Union, China, Eastern Europe, Cuba, et al, Kennedy saw that winning a war in a peasant country on the side of the landlords in South Vietnam was both unjust and unwinnable and knew better than anyone alive, from being the only person in the room with the Soviet ambassador in 1962 for the last chance to resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis, the risk of global obliteration by nuclear war. He made clear that South Vietnam must conduct a massive land reform giving the land to the poor and hungry landless peasants of the Mekong Delta, the majority of the population and the foot soldiers of the Viet Cong, allied with the North Vietnamese in fighting the South Vietnamese government. After he died, the land reform came, and Viet Cong recruiting among the peasants fell off to virtually nothing, but too late for American support to continue for a war-weary public, and too late for South Vietnam to survive.

Kennedy running against him was clearly the final straw for LBJ. And only a bullet kept Bobby Kennedy from becoming president. The argument that he didn’t control the machine, which might stop him, was absurd. He knew the machine better than anyone as JFK’s campaign manager and then virtually his co-president as Attorney General. Now he had the weight of popular will and history carrying him like a tidal wave, with an unprecedented cross-racial coalition of voters behind him

King and Kennedy were mainly aligned. The first bullet came for King, in only days. Had both lived, we would be in a different world today.

On the day LBJ withdrew from the race for the presidency, King gave one of his last sermons at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., five days before he was assasinated in Memphis.

Here is an excerpt.

“Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution”:

I would like to use as a subject from which to preach this morning: “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution.” The text for the morning is found in the book of Revelation. There are two passages there that I would like to quote, in the sixteenth chapter of that book: “Behold I make all things new; former things are passed away.”

I am sure that most of you have read that arresting little story from the pen of Washington Irving entitled “Rip Van Winkle.” The one thing that we usually remember about the story is that Rip Van Winkle slept twenty years. But there is another point in that little story that is almost completely overlooked. It was the sign in the end, from which Rip went up in the mountain for his long sleep.

When Rip Van Winkle went up into the mountain, the sign had a picture of King George the Third of England. When he came down twenty years later the sign had a picture of George Washington, the first president of the United States. When Rip Van Winkle looked up at the picture of George Washington—and looking at the picture he was amazed—he was completely lost. He knew not who he was.

And this reveals to us that the most striking thing about the story of Rip Van Winkle is not merely that Rip slept twenty years, but that he slept through a revolution. While he was peacefully snoring up in the mountain a revolution was taking place that at points would change the course of history—and Rip knew nothing about it. He was asleep. Yes, he slept through a revolution. And one of the great liabilities of life is that all too many people find themselves living amid a great period of social change, and yet they fail to develop the new attitudes, the new mental responses, that the new situation demands. They end up sleeping through a revolution.

There can be no gainsaying of the fact that a great revolution is taking place in the world today. In a sense it is a triple revolution: that is, a technological revolution, with the impact of automation and cybernation; then there is a revolution in weaponry, with the emergence of atomic and nuclear weapons of warfare; then there is a human rights revolution, with the freedom explosion that is taking place all over the world. Yes, we do live in a period where changes are taking place. And there is still the voice crying through the vista of time saying, “Behold, I make all things new; former things are passed away.”

Now whenever anything new comes into history it brings with it new challenges and new opportunities. And I would like to deal with the challenges that we face today as a result of this triple revolution that is taking place in the world today.

First, we are challenged to develop a world perspective. No individual can live alone, no nation can live alone, and anyone who feels that he can live alone is sleeping through a revolution. The world in which we live is geographically one. The challenge that we face today is to make it one in terms of brotherhood.

Now it is true that the geographical oneness of this age has come into being to a large extent through modern man’s scientific ingenuity. Modern man through his scientific genius has been able to dwarf distance and place time in chains. And our jet planes have compressed into minutes distances that once took weeks and even months. All of this tells us that our world is a neighborhood.

Through our scientific and technological genius, we have made of this world a neighborhood and yet we have not had the ethical commitment to make of it a brotherhood. But somehow, and in some way, we have got to do this. We must all learn to live together as brothers or we will all perish together as fools. We are tied together in the single garment of destiny, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality. And whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. For some strange reason I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. And you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be.

Again, just five days later, King was shot and killed on the balcony of a Memphis motel.

That night, Bobby Kennedy heard the news on the way to a rally for his presidential campaign in the Indianapolis ghetto. He was told by the police not to go, the inner-cities across America were exploding in protests from the agony of the news. They said they couldn’t protect him and wouldn’t go with him.

He said he didn’t care.

A huge crowd, as always in that last campaigh, awaited him, mostly Black. They hadn’t heard the news.

On Memorial Day, 2020, The Atlantic ran the following article on Kennedy’s speech to the crowd that night:

America Used to Have Leaders

Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 speech following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination offers a stark lesson in what has changed—and what remains the same—more than 50 years later.

MAY 31, 2020

Editor’s Note: On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. That night, as explosive protests broke out across the country, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a presidential candidate at the time, gave the following speech in Indianapolis. Much has changed in America since 1968, yet Kennedy’s words offer a stark lesson in contrasting leadership styles in 2020. They also remind us that the nation is still broken in many of the ways that it was more than 50 years ago, as the pain caused by racial violence endures.

I have bad news for you, for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and killed tonight.

Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice for his fellow human beings, and he died because of that effort.

In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black—considering the evidence there evidently is that there were white people who were responsible—you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization—black people amongst black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another.

Photos: The riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.

For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.

Read: Are they police departments or armies?

My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He wrote: “In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.”

What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness, but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black.

So I shall ask you tonight to return home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King, that’s true, but more importantly, to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love—a prayer for understanding and that compassion of which I spoke.

We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times; we’ve had difficult times in the past; we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; it is not the end of disorder.

But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings who abide in our land.

Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.

Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and for our people.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

. . .

This was the first time Bobby Kennedy ever uttered a word publicly about the assasination, five years earlier, of his brother, President Kennedy. He never did again. Two months later, the funeral train with tracks lined with thousands of mourners, would be for him.

. . .

This weekend, the Divisional Round playoff games of the NFL are occurring, with the phrase “Choose Love” displayed in the end zones and on helmet decals, with the same thing slated to continue in the Super Bowl, to honor the memory of King.

Without commenting here on the context of the NFL, the word love with relationship to King, and to reality if it’s real love, is tougher than the game itself. For King, it meant the grotesquely unequal and exploitive power structure of the world, by far more now than ever, is either transformed or comes tumbling down. You can be sure the phrase was meant to avoid real love and the real King, and was branding to go for the comfort of soft and fuzzy. “I have a dream”. No lay it all down to actually get there.

But you can also be sure no one is actually paying attention anymore. It will be a fleeting moment of “Oh, isn’t that nice” if anyone does.

The last time King’s name and the holiday were still worth anything, in terms of people paying attention, it was for all the wrong reasons, and it also intersected with the Super Bowl.

More importantly, it hallmarked the cultural dive into a multidimensional Orwellian “1984” of timeless principles cast aside, greed, self-gratification, nihilism, narcisism and the meaningless void we had taken for some time and have been accelerating ever since. The price of the rich and powerful taking more and more, with their technological tools addicting everyone, even them, accompanied by the real danger of the tools becoming the new dystopian masters, along with all the usual costs of inequality and insecurity. As opposed to taking the road of providing universal human rights and needs that King and so many throughout history had called us to as not only the moral road, but the only road to sustainable survival. We’d seen from that mountain top more than once, then been knocked off, and seem quite possibly now to be in the last stages of the “long twilight struggle” over principles of decency and survival, at least in the dynamic of human evolution so far, that JFK described in his inaugural address on January 20, 1961, the 65th anniversary of which is one day after Martin Luther King, Jr. Day this year.

Here’s a part of our commentary in the Issue of the Week, 2.10.2018:

One of the hallmarks of the Super Bowl is that it’s also the Super Bowl of advertising–that medium generally used to feed every most base impulse we have to consume.

So, we’re watching, live, as monitoring media and culture is a critical part of our work, which public service advertising has also been a critical part of.

The image is of a Dodge Ram truck. The voiceover sounds so familiar. But its instantly brain-exploding and you don’t at first know why.

NO! That is NOT the voice of Martin Luther King, Jr.!

NO! that is NOT his famous “The Drum Major Instinct” speech of exactly 50 years before to the day!

NOT at the start of this 50th anniversary year of that year of years in the US and around the world–Vietnam (this is the 50th anniversary of the second week of the Tet Offensive) and Civil Rights and King and Kennedy and on and on–1968.

The New York Times reported:

“The online blowback was swift for Ram on Sunday after the carmaker used a sermon given by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as the voice-over for a Super Bowl ad. …

The commercial showed scenes of people helping others while Dr. King extolled the virtues of service. At the end, the phrase “Built to Serve” was shown on the screen, along with the Ram logo. …

Adding to the disconnect, the sermon in question, delivered exactly 50 years ago, touched on the danger of overspending on items like cars and discussed why people “are so often taken by advertisers.” That was not lost on the ad’s detractors.

The general sentiment: Did the company really just use Dr. King’s words about the value of service to sell trucks?

The King Center said on Twitter that neither the organization nor the Rev. Bernice King, one of Dr. King’s daughters, is responsible for approving his “words or imagery for use in merchandise, entertainment (movies, music, artwork, etc) or advertisement.” It said that included the Super Bowl commercial.

Ram approached Dr. King’s estate about using his voice in the commercial, said Eric D. Tidwell, the managing director of Intellectual Properties Management, the licenser of the estate.

“Once the final creative was presented for approval, it was reviewed to ensure it met our standard integrity clearances,” Mr. Tidwell said in a statement. “We found that the overall message of the ad embodied Dr. King’s philosophy that true greatness is achieved by serving others.”

Ergo, the holistic nature of everything cannibalizing everything. The New York Times editorialized the next day:

“Making Dr. King a Pitchman, Turning His Words Upside Down”:

William Bernbach, a titan of Madison Avenue who died in 1982, said, “If your advertising goes unnoticed, everything else is academic.” The spinmeisters for Ram trucks must have taken Mr. Bernbach’s admonition to heart. With a Super Bowl commercial on Sunday that used as its soundtrack a sermon delivered by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. 50 years earlier to the day, they got the notice they wanted. Much of the reaction, though, amounted to a richly deserved thumbs-down.

The sermon was Dr. King’s “Drum Major Instinct” speech, given in Atlanta in 1968 two months before his assassination.

Everybody, he said, had this instinct — “a desire to be out front, a desire to lead the parade, a desire to be first.” But it had to be harnessed, he said as he went on to equate greatness with service to others. Ostensibly, the Ram commercial was an appeal for people to serve. But who’s kidding whom? The goal was to sell trucks, with Dr. King’s voice as pitchman.

The sheer crassness led to instant condemnation on social media, including speculation about what might be next — maybe trotting out James Baldwin to hawk “The Firestone Next Time”? Critics were hardly mollified by word that Ram had the blessing of Intellectual Properties Management, the licenser of Dr. King’s estate. The estate has not always been his staunchest guardian against posthumous commercialization.

It might serve history a tad more faithfully to note other appeals that Dr. King made in that Feb. 4, 1968, sermon. For one thing, he was appalled by the way many people went into hock to buy vehicles they couldn’t possibly afford: “So often, haven’t you seen people making $5,000 a year and driving a car that cost 6,000? And they wonder why their ends never meet.”

While we’re at it, he also didn’t think highly of advertising gurus — “you know, those gentlemen of massive verbal persuasion.” He continued: “They have a way of saying things to you that kind of gets you into buying. In order to be a man of distinction, you must drink this whiskey. In order to make your neighbors envious, you must drive this type of car. In order to be lovely to love, you must wear this kind of lipstick or this kind of perfume. And you know, before you know it, you’re just buying that stuff.”

For that matter, Dr. King might well have been talking about a president a half-century in the future when he expounded on the need to rein in the drum major instinct, for otherwise it becomes “very dangerous” and “pernicious.”

“Have you ever heard people that, you know — and I’m sure you’ve met them — that really become sickening because they just sit up all the time talking about themselves?” he said. “And they just boast and boast and boast. And that’s the person who has not harnessed the drum major instinct.”

In the sermon’s finale, Dr. King said that he thought about his own death and funeral. It led to these ringing words: “If you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter.”

He did not ask to be a huckster for a line of trucks.”

A line from a version of The Three Evils of Society speech King gave in August 1967 in Chicago stands out:

Millions, yes billions, are appropriated for mass murder; but the most meager pittance for foreign aid for international development. . .

That was then.

There were good reasons for some of those billions being spent on defense, including, horribly beyond words, for weapons of mass destruction. But only in the context of continuing arms control talks, and particularly arms reduction, stopping proliferation and eventually eliminating nuclear weapons to every extent possible. President Kennedy started down this path, LBJ continued even during the Vietnam War, and so did every president to follow, with the end of the Cold War bringing the greatest reductions and greatest hope for the future–for a while. Now, there is no apparent pursuit of arms control, but the opposite, from the US, Russia, China and others. We are on the edge of a proliferation of nations getting nuclear weapons as never before, mainly because the protection, policies and alliances promoted by the US, despite all its faults, for a more stable future after World War Two, are potentially coming apart at the moment because of US policy becoming unpredictable and willing to abandon the global protection of liberal democracy, again despite all its mistakes, it had successfully championed in the main.

But the flip side of the coin King remarked on was the huge discrepancy between spending on weapons and on international development, which is to say in ending hunger, disease, poverty and creating sustainable and stable lives, communities and nations.

Eventually, much progress was made after King’s remarks over the decades. Much more needed to be. But then, the agency for the “international development” King spoke of, USAID, which most of the aid for the poor and hungry and those in need in the world went through, was destroyed, in virtually a day. USAID had been formailized as the agency to provide aid for international development by President Kennedy in 1961. Hundreds of millions had been saved, mostly children. Hundreds of milions were now doomed, mostly children. And the sparks of future war were fed with gasoline.

In America, much the same story, of the most successful poverty reducing, hunger reducing, disease reducing and sustainable health and life-enhancing programs decimated.

Whites suffering the most in numbers, Blacks in percentage, then Latinos and all others.

The amount spent on these programs was more than when King spoke of the evil of all this in 1967, but still a pittance compared with the whole budget, sometimes because the programs were so efficient (one of the great ironies of the big lie about cutting for efficiency), sometimes because the priority had still been not just defense, but far more costly and unjustly, trillions of tax cuts for the richest people and corporations in history by far, who control the huge majority of global wealth more than ever every day.

Martin Luther King, Jr., in his worst nightmares, never would likely have imagined this dystoptian science fiction at the bottom level of Dante’s levels of Hell. Yet, he knew it was possible. He warned of what would happen if we didn’t go the other way then, much less now.

Again, as noted above, he’s the only one in American history with the holiday this day represents.

So how do we avoid the greatest call to accountability ever from the prophet we gave this unique position?

The below are taken from the 50th anniversary of King’s assasination special edition in The Atlantic, with many other articles linked that are must reads.

Here are the Letter from Birmingham Jail and Martin Luther King Jr. Saw Three Evils In The World:

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.’S ‘LETTER FROM BIRMINGHAM JAIL’

“We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom.” By Martin Luther King Jr.

Editor’s Note: Read The Atlantic’s special coverage of Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy.

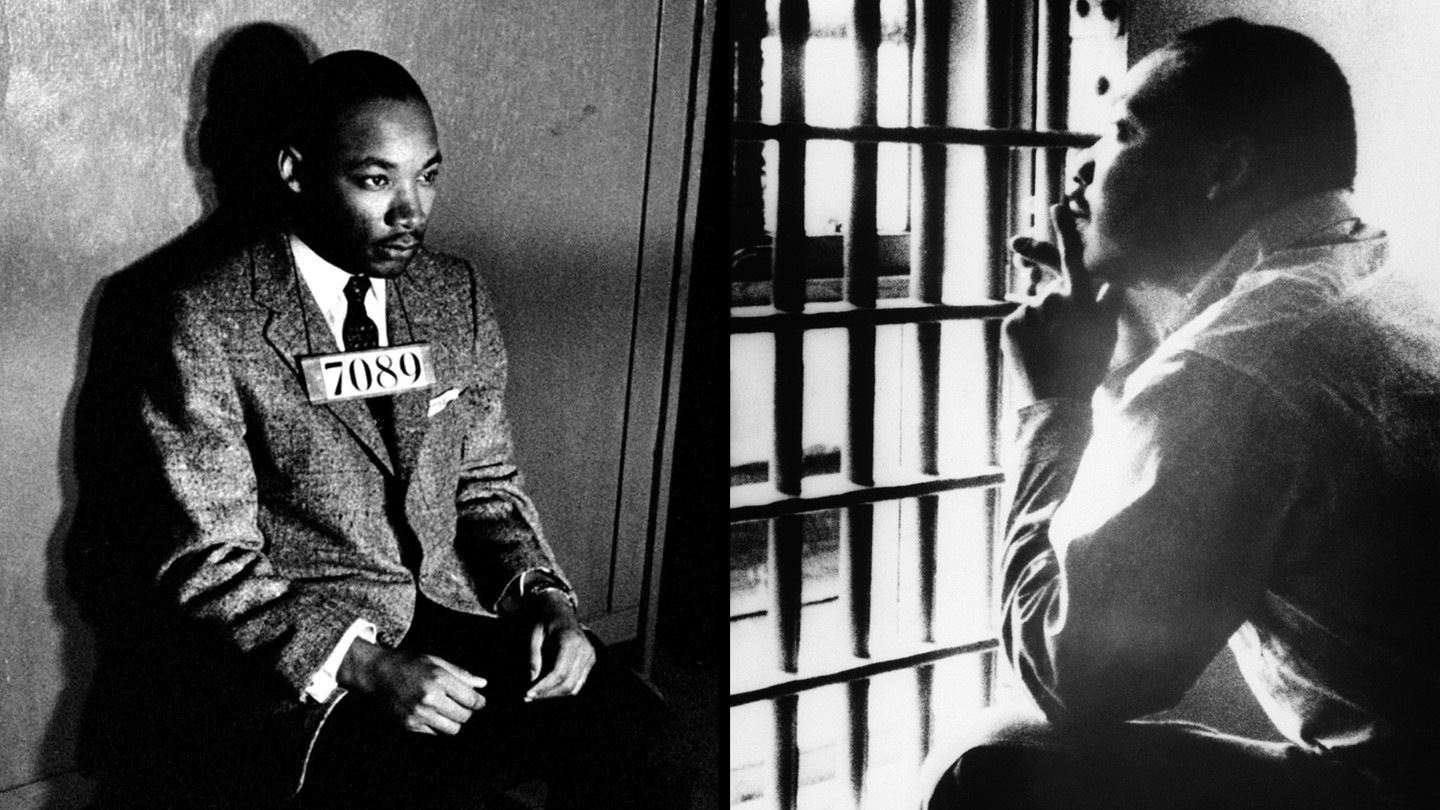

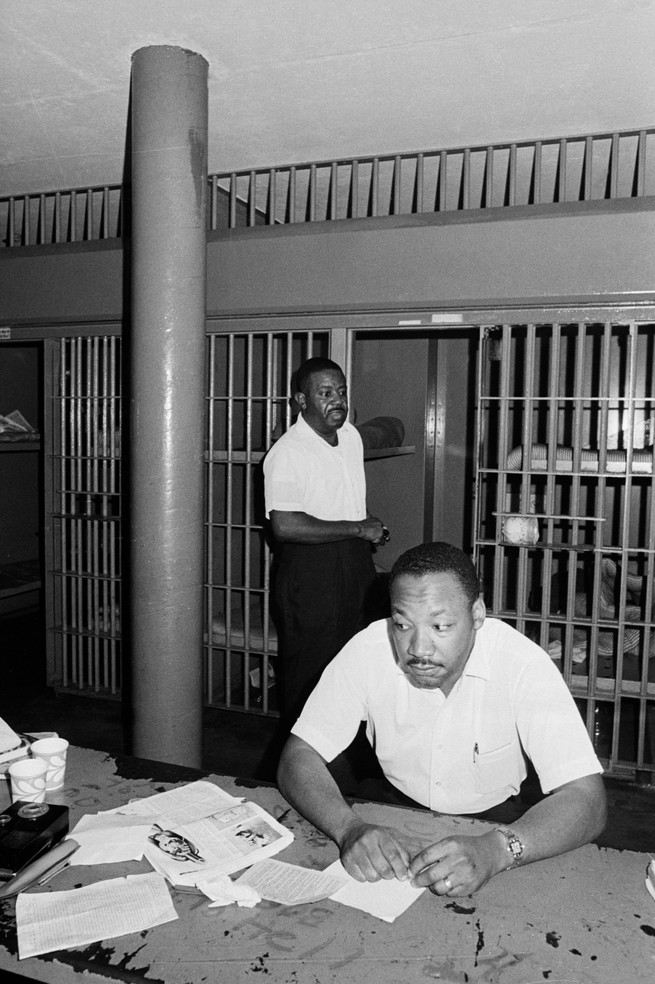

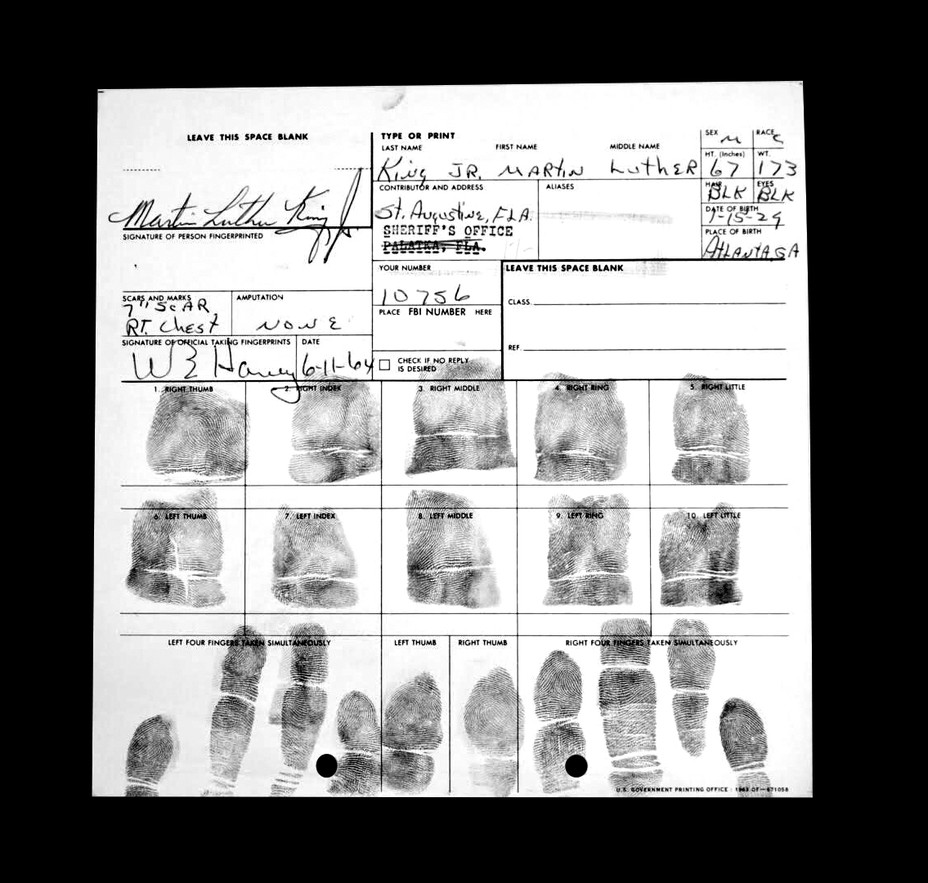

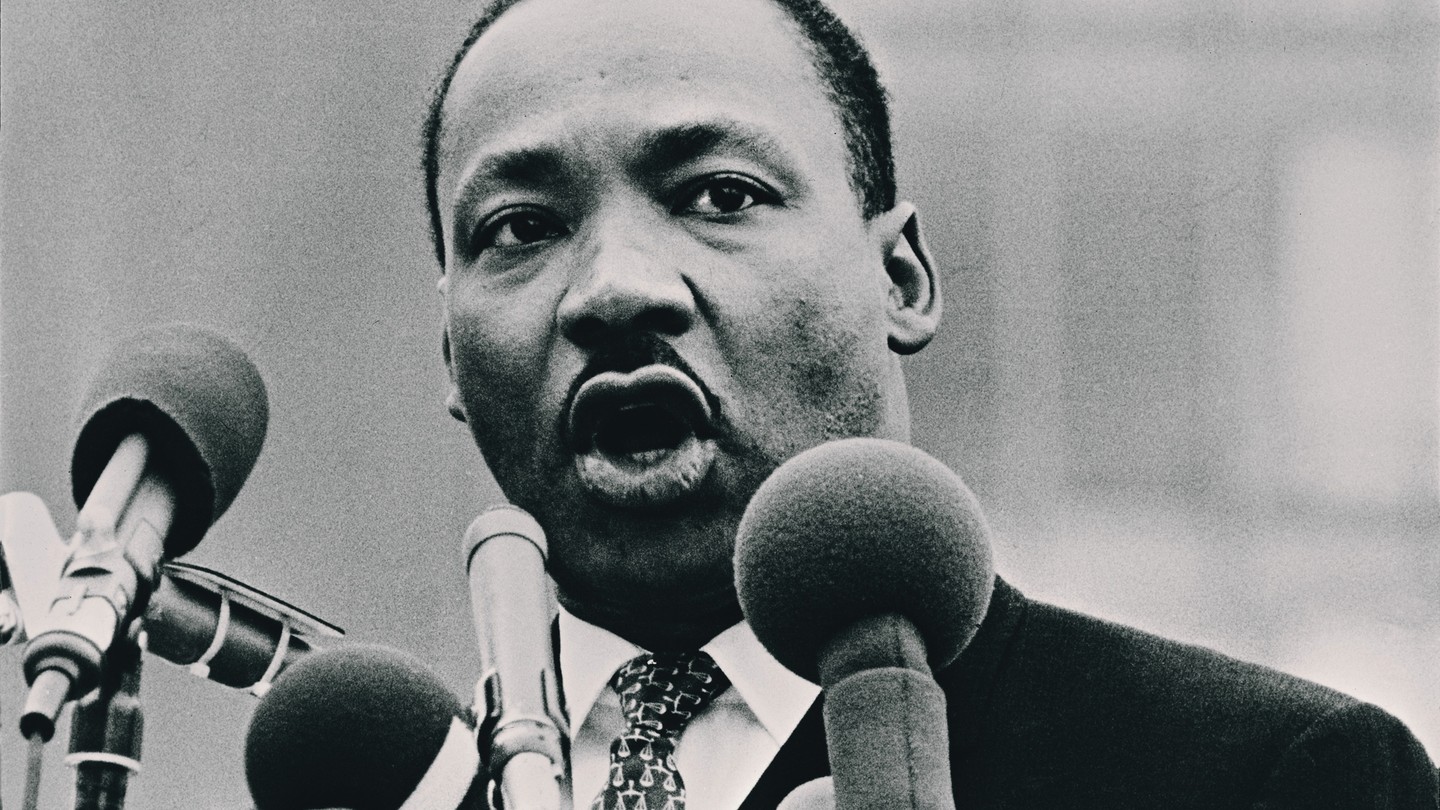

Images above: King is ready for a mug shot (left) in Montgomery, Alabama, after his 1956 arrest while protesting the segregation of the city’s buses. His leadership of the successful 381-day bus boycott brought him to national attention. Right: In 1967, King serves out the sentence from his arrest four years earlier in Birmingham, Alabama.

In April 1963, King was jailed in Birmingham, Alabama, after he defied a state court’s injunction and led a march of black protesters without a permit, urging an Easter boycott of white-owned stores. A statement published in The Birmingham News, written by eight moderate white clergymen, criticized the march and other demonstrations.

This prompted King to write a lengthy response, begun in the margins of the newspaper. He smuggled it out with the help of his lawyer, and the nearly 7,000 words were transcribed. The eloquent call for “constructive, nonviolent tension” to force an end to unjust laws became a landmark document of the civil-rights movement. The letter was printed in part or in full by several publications, including the New York Post, Liberation magazine, The New Leader, and The Christian Century.

The Atlantic published it in the August 1963 issue, under the headline “The Negro Is Your Brother.”

My Dear Fellow Clergymen:

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities “unwise and untimely.” Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If I sought to answer all the criticisms that cross my desk, my secretaries would have little time for anything other than such correspondence in the course of the day, and I would have no time for constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.

I think I should indicate why I am here in Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against “outsiders coming in.” I have the honor of serving as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization operating in every southern state, with headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia. We have some eighty-five affiliated organizations across the South, and one of them is the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Frequently we share staff, educational and financial resources with our affiliates. Several months ago the affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call to engage in a nonviolent direct-action program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and when the hour came we lived up to our promise. So I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here.

But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century b.c. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco-Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.

Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.

In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action. We have gone through all these steps in Birmingham. There can be no gainsaying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in good-faith negotiation.

Then, last September, came the opportunity to talk with leaders of Birmingham’s economic community. In the course of the negotiations, certain promises were made by the merchants—for example, to remove the stores’ humiliating racial signs. On the basis of these promises, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the leaders of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights agreed to a moratorium on all demonstrations. As the weeks and months went by, we realized that we were the victims of a broken promise. A few signs, briefly removed, returned; the others remained.

As in so many past experiences, our hopes had been blasted, and the shadow of deep disappointment settled upon us. We had no alternative except to prepare for direct action, whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and the national community. Mindful of the difficulties involved, we decided to undertake a process of self-purification. We began a series of workshops on nonviolence, and we repeatedly asked ourselves: “Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?” “Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?” We decided to schedule our direct-action program for the Easter season, realizing that except for Christmas, this is the main shopping period of the year. Knowing that a strong economic-withdrawal program would be the by—product of direct action, we felt that this would be the best time to bring pressure to bear on the merchants for the needed change.“Wait” has almost always meant “Never.”

Then it occurred to us that the March election [for Birmingham’s mayor] was ahead, and so we speedily decided to postpone action until after election day. When we discovered that Mr. Connor [the commissioner of public safety, Eugene “Bull” Connor] was in the runoff, we decided again to postpone action so that the demonstration could not be used to cloud the issues. Like many others, we waited to see Mr. Connor defeated, and to this end we endured postponement after postponement. Having aided in this community need, we felt that our direct-action program could be delayed no longer.

You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent-resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

The purpose of our direct-action program is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. I therefore concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue.

Explore the KING Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.View More

One of the basic points in your statement is that the action that I and my associates have taken in Birmingham is untimely. Some have asked: “Why didn’t you give the new city administration time to act?” The only answer that I can give to this query is that the new Birmingham administration must be prodded about as much as the outgoing one, before it will act. We are sadly mistaken if we feel that the election of Albert Boutwell as mayor will bring the millennium to Birmingham. While Mr. Boutwell is a much more gentle person than Mr. Connor, they are both segregationists, dedicated to maintenance of the status quo. I have hope that Mr. Boutwell will be reasonable enough to see the futility of massive resistance to desegregation. But he will not see this without pressure from devotees of civil rights. My friends, I must say to you that we have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct-action campaign that was “well timed” in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horse-and-buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter. Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five-year-old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross-country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”—then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.

You express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, at first glance it may seem rather paradoxical for us consciously to break laws. One may well ask: “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?” The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.”

Now, what is the difference between the two? How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas: An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. Segregation, to use the terminology of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, substitutes an “I–it” relationship for an “I–thou” relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things. Hence segregation is not only politically, economically and sociologically unsound, it is morally wrong and sinful. Paul Tillich has said that sin is separation. Is not segregation an existential expression of man’s tragic separation, his awful estrangement, his terrible sinfulness? Thus it is that I can urge men to obey the 1954 decision of the Supreme Court, for it is morally right; and I can urge them to disobey segregation ordinances, for they are morally wrong.

Let us consider a more concrete example of just and unjust laws. An unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself. This is difference made legal. By the same token, a just law is a code that a majority compels a minority to follow and that it is willing to follow itself. This is sameness made legal.

Let me give another explanation. A law is unjust if it is inflicted on a minority that, as a result of being denied the right to vote, had no part in enacting or devising the law. Who can say that the legislature of Alabama which set up that state’s segregation laws was democratically elected? Throughout Alabama all sorts of devious methods are used to prevent Negroes from becoming registered voters, and there are some counties in which, even though Negroes constitute a majority of the population, not a single Negro is registered. Can any law enacted under such circumstances be considered democratically structured?

Sometimes a law is just on its face and unjust in its application. For instance, I have been arrested on a charge of parading without a permit. Now, there is nothing wrong in having an ordinance which requires a permit for a parade. But such an ordinance becomes unjust when it is used to maintain segregation and to deny citizens the First-Amendment privilege of peaceful assembly and protest.

I hope you are able to see the distinction I am trying to point out. In no sense do I advocate evading or defying the law, as would the rabid segregationist. That would lead to anarchy. One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty. I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.

Of course, there is nothing new about this kind of civil disobedience. It was evidenced sublimely in the refusal of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego to obey the laws of Nebuchadnezzar, on the ground that a higher moral law was at stake. It was practiced superbly by the early Christians, who were willing to face hungry lions and the excruciating pain of chopping blocks rather than submit to certain unjust laws of the Roman Empire. To a degree, academic freedom is a reality today because Socrates practiced civil disobedience. In our own nation, the Boston Tea Party represented a massive act of civil disobedience.

We should never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was “legal” and everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was “illegal.” It was “illegal” to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler’s Germany. Even so, I am sure that, had I lived in Germany at the time, I would have aided and comforted my Jewish brothers. If today I lived in a Communist country where certain principles dear to the Christian faith are suppressed, I would openly advocate disobeying that country’s antireligious laws.

Explore the KING Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.View More

I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens’ Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress. I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that the present tension in the South is a necessary phase of the transition from an obnoxious negative peace, in which the Negro passively accepted his unjust plight, to a substantive and positive peace, in which all men will respect the dignity and worth of human personality. Actually, we who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with all its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.The question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love?

In your statement you assert that our actions, even though peaceful, must be condemned because they precipitate violence. But is this a logical assertion? Isn’t this like condemning a robbed man because his possession of money precipitated the evil act of robbery? Isn’t this like condemning Socrates because his unswerving commitment to truth and his philosophical inquiries precipitated the act by the misguided populace in which they made him drink hemlock? Isn’t this like condemning Jesus because his unique God-consciousness and never-ceasing devotion to God’s will precipitated the evil act of crucifixion? We must come to see that, as the federal courts have consistently affirmed, it is wrong to urge an individual to cease his efforts to gain his basic constitutional rights because the quest may precipitate violence. Society must protect the robbed and punish the robber.

I had also hoped that the white moderate would reject the myth concerning time in relation to the struggle for freedom. I have just received a letter from a white brother in Texas. He writes: “All Christians know that the colored people will receive equal rights eventually, but it is possible that you are in too great a religious hurry. It has taken Christianity almost two thousand years to accomplish what it has. The teachings of Christ take time to come to earth.” Such an attitude stems from a tragic misconception of time, from the strangely irrational notion that there is something in the very flow of time that will inevitably cure all ills. Actually, time itself is neutral; it can be used either destructively or constructively. More and more I feel that the people of ill will have used time much more effectively than have the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people. Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be coworkers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right. Now is the time to make real the promise of democracy and transform our pending national elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood. Now is the time to lift our national policy from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of human dignity.

You speak of our activity in Birmingham as extreme. At first I was rather disappointed that fellow clergymen would see my nonviolent efforts as those of an extremist. I began thinking about the fact that I stand in the middle of two opposing forces in the Negro community. One is a force of complacency, made up in part of Negroes who, as a result of long years of oppression, are so drained of self-respect and a sense of “somebodiness” that they have adjusted to segregation; and in part of a few middle-class Negroes who, because of a degree of academic and economic security and because in some ways they profit by segregation, have become insensitive to the problems of the masses. The other force is one of bitterness and hatred, and it comes perilously close to advocating violence. It is expressed in the various black nationalist groups that are springing up across the nation, the largest and best known being Elijah Muhammad’s Muslim movement. Nourished by the Negro’s frustration over the continued existence of racial discrimination, this movement is made up of people who have lost faith in America, who have absolutely repudiated Christianity, and who have concluded that the white man is an incorrigible “devil.”

I have tried to stand between these two forces, saying that we need emulate neither the “do-nothingism” of the complacent nor the hatred and despair of the black nationalist. For there is the more excellent way of love and nonviolent protest. I am grateful to God that, through the influence of the Negro church, the way of nonviolence became an integral part of our struggle.

If this philosophy had not emerged, by now many streets of the South would, I am convinced, be flowing with blood. And I am further convinced that if our white brothers dismiss as “rabble-rousers” and “outside agitators” those of us who employ nonviolent direct action, and if they refuse to support our nonviolent efforts, millions of Negroes will, out of frustration and despair, seek solace and security in black-nationalist ideologies—a development that would inevitably lead to a frightening racial nightmare.

Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever. The yearning for freedom eventually manifests itself, and that is what has happened to the American Negro. Something within has reminded him of his birthright of freedom, and something without has reminded him that it can be gained. Consciously or unconsciously, he has been caught up by the Zeitgeist, and with his black brothers of Africa and his brown and yellow brothers of Asia, South America and the Caribbean, the United States Negro is moving with a sense of great urgency toward the promised land of racial justice. If one recognizes this vital urge that has engulfed the Negro community, one should readily understand why public demonstrations are taking place. The Negro has many pent-up resentments and latent frustrations, and he must release them. So let him march; let him make prayer pilgrimages to the city hall; let him go on Freedom Rides—and try to understand why he must do so. If his repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat but a fact of history. So I have not said to my people: “Get rid of your discontent.” Rather, I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist.

But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.” Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Was not Martin Luther an extremist: “Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God.” And John Bunyan: “I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience.” And Abraham Lincoln: “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” And Thomas Jefferson: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal …” So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary’s hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime—the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists.

I had hoped that the white moderate would see this need. Perhaps I was too optimistic; perhaps I expected too much. I suppose I should have realized that few members of the oppressor race can understand the deep groans and passionate yearnings of the oppressed race, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent and determined action. I am thankful, however, that some of our white brothers in the South have grasped the meaning of this social revolution and committed themselves to it. They are still all too few in quantity, but they are big in quality. Some—such as Ralph McGill, Lillian Smith, Harry Golden, James McBride Dabbs, Anne Braden and Sarah Patton Boyle—have written about our struggle in eloquent and prophetic terms. Others have marched with us down nameless streets of the South. They have languished in filthy, roach-infested jails, suffering the abuse and brutality of policemen who view them as “dirty nigger-lovers.” Unlike so many of their moderate brothers and sisters, they have recognized the urgency of the moment and sensed the need for powerful “action” antidotes to combat the disease of segregation.

Let me take note of my other major disappointment. I have been so greatly disappointed with the white church and its leadership. Of course, there are some notable exceptions. I am not unmindful of the fact that each of you has taken some significant stands on this issue. I commend you, Reverend Stallings, for your Christian stand on this past Sunday, in welcoming Negroes to your worship service on a nonsegregated basis. I commend the Catholic leaders of this state for integrating Spring Hill College several years ago.

But despite these notable exceptions, I must honestly reiterate that I have been disappointed with the church. I do not say this as one of those negative critics who can always find something wrong with the church. I say this as a minister of the gospel, who loves the church; who was nurtured in its bosom; who has been sustained by its spiritual blessings and who will remain true to it as long as the cord of life shall lengthen.

When I was suddenly catapulted into the leadership of the bus protest in Montgomery, Alabama, a few years ago, I felt we would be supported by the white church. I felt that the white ministers, priests and rabbis of the South would be among our strongest allies. Instead, some have been outright opponents, refusing to understand the freedom movement and misrepresenting its leaders; all too many others have been more cautious than courageous and have remained silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained-glass windows.

In spite of my shattered dreams, I came to Birmingham with the hope that the white religious leadership of this community would see the justice of our cause and, with deep moral concern, would serve as the channel through which our just grievances could reach the power structure. I had hoped that each of you would understand. But again I have been disappointed.

I have heard numerous southern religious leaders admonish their worshipers to comply with a desegregation decision because it is the law, but I have longed to hear white ministers declare: “Follow this decree because integration is morally right and because the Negro is your brother.” In the midst of blatant injustices inflicted upon the Negro, I have watched white churchmen stand on the sideline and mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities. In the midst of a mighty struggle to rid our nation of racial and economic injustice, I have heard many ministers say: “Those are social issues, with which the gospel has no real concern.” And I have watched many churches commit themselves to a completely otherworldly religion which makes a strange, un-Biblical distinction between body and soul, between the sacred and the secular.

I have traveled the length and breadth of Alabama, Mississippi and all the other southern states. On sweltering summer days and crisp autumn mornings I have looked at the South’s beautiful churches with their lofty spires pointing heavenward. I have beheld the impressive outlines of her massive religious—education buildings. Over and over I have found myself asking: “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God? Where were their voices when the lips of Governor Barnett dripped with words of interposition and nullification? Where were they when Governor Wallace gave a clarion call for defiance and hatred? Where were their voices of support when bruised and weary Negro men and women decided to rise from the dark dungeons of complacency to the bright hills of creative protest?”

Yes, these questions are still in my mind. In deep disappointment I have wept over the laxity of the church. But be assured that my tears have been tears of love. There can be no deep disappointment where there is not deep love. Yes, I love the church. How could I do otherwise? I am in the rather unique position of being the son, the grandson and the great-grandson of preachers. Yes, I see the church as the body of Christ. But, oh! How we have blemished and scarred that body through social neglect and through fear of being nonconformists.

There was a time when the church was very powerful—in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society. Whenever the early Christians entered a town, the people in power became disturbed and immediately sought to convict the Christians for being “disturbers of the peace” and “outside agitators.” But the Christians pressed on, in the conviction that they were “a colony of heaven,” called to obey God rather than man. Small in number, they were big in commitment. They were too God-intoxicated to be “astronomically intimidated.” By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests.

Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent—and often even vocal—sanction of things as they are.

But the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust.

Perhaps I have once again been too optimistic. Is organized religion too inextricably bound to the status quo to save our nation and the world? Perhaps I must turn my faith to the inner spiritual church, the church within the church, as the true ekklesia and the hope of the world. But again I am thankful to God that some noble souls from the ranks of organized religion have broken loose from the paralyzing chains of conformity and joined us as active partners in the struggle for freedom. They have left their secure congregations and walked the streets of Albany, Georgia, with us. They have gone down the highways of the South on tortuous rides for freedom. Yes, they have gone to jail with us. Some have been dismissed from their churches, have lost the support of their bishops and fellow ministers. But they have acted in the faith that right defeated is stronger than evil triumphant. Their witness has been the spiritual salt that has preserved the true meaning of the gospel in these troubled times. They have carved a tunnel of hope through the dark mountain of disappointment.

I hope the church as a whole will meet the challenge of this decisive hour. But even if the church does not come to the aid of justice, I have no despair about the future. I have no fear about the outcome of our struggle in Birmingham, even if our motives are at present misunderstood. We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom. Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with America’s destiny. Before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth, we were here. Before the pen of Jefferson etched the majestic words of the Declaration of Independence across the pages of history, we were here. For more than two centuries our forebears labored in this country without wages; they made cotton king; they built the homes of their masters while suffering gross injustice and shameful humiliation—and yet out of a bottomless vitality they continued to thrive and develop. If the inexpressible cruelties of slavery could not stop us, the opposition we now face will surely fail. We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.

Before closing I feel impelled to mention one other point in your statement that has troubled me profoundly. You warmly commended the Birmingham police force for keeping “order” and “preventing violence.” I doubt that you would have so warmly commended the police force if you had seen its dogs sinking their teeth into unarmed, nonviolent Negroes. I doubt that you would so quickly commend the policemen if you were to observe their ugly and inhumane treatment of Negroes here in the city jail; if you were to watch them push and curse old Negro women and young Negro girls; if you were to see them slap and kick old Negro men and young boys; if you were to observe them, as they did on two occasions, refuse to give us food because we wanted to sing our grace together. I cannot join you in your praise of the Birmingham police department.

It is true that the police have exercised a degree of discipline in handling the demonstrators. In this sense they have conducted themselves rather “nonviolently” in public. But for what purpose? To preserve the evil system of segregation. Over the past few years I have consistently preached that nonviolence demands that the means we use must be as pure as the ends we seek. I have tried to make clear that it is wrong to use immoral means to attain moral ends. But now I must affirm that it is just as wrong, or perhaps even more so, to use moral means to preserve immoral ends. Perhaps Mr. Connor and his policemen have been rather nonviolent in public, as was Chief Pritchett in Albany, Georgia, but they have used the moral means of non-violence to maintain the immoral end of racial injustice. As T. S. Eliot has said: “The last temptation is the greatest treason: To do the right deed for the wrong reason.”

I wish you had commended the Negro sit-inners and demonstrators of Birmingham for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer and their amazing discipline in the midst of great provocation. One day the South will recognize its real heroes. They will be the James Merediths, with the noble sense of purpose that enables them to face jeering and hostile mobs, and with the agonizing loneliness that characterizes the life of the pioneer. They will be old, oppressed, battered Negro women, symbolized in a seventy-two-year-old woman in Montgomery, Alabama, who rose up with a sense of dignity and with her people decided not to ride segregated buses, and who responded with ungrammatical profundity to one who inquired about her weariness: “My feets is tired, but my soul is at rest.” They will be the young high school and college students, the young ministers of the gospel and a host of their elders, courageously and nonviolently sitting in at lunch counters and willingly going to jail for conscience sake. One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters, they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judaeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

Never before have I written so long a letter. I’m afraid it is much too long to take your precious time. I can assure you that it would have been much shorter if I had been writing from a comfortable desk, but what else can one do when he is alone in a narrow jail cell, other than write long letters, think long thoughts and pray long prayers?

If I have said anything in this letter that overstates the truth and indicates an unreasonable impatience, I beg you to forgive me. If I have said anything that understates the truth and indicates my having a patience that allows me to settle for anything less than brotherhood, I beg God to forgive me.

I hope this letter finds you strong in the faith. I also hope that circumstances will soon make it possible for me to meet each of you, not as an integrationist or a civil-rights leader but as a fellow clergyman and a Christian brother. Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear-drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

Yours for the cause of Peace and Brotherhood,

Martin Luther King Jr.

. . .

Editor’s Note: Read The Atlantic’s special coverage of Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. SAW THREE EVILS IN THE WORLD

Racism was only the first. By Martin Luther King Jr.

The Hungry Club Forum began as a secret initiative of the Butler Street YMCA, in Atlanta. It was a place where sympathetic white politicians could meet out of the public eye with local black leaders, who were excluded from many of the city’s civic organizations. King, an Atlanta native, addressed the club on May 10, 1967. He acknowledged that progress had been made in civil rights, but warned that the “evils” of racism, poverty, and the Vietnam War endangered further gains for black Americans.

Three major evils—the evil of racism, the evil of poverty, and the evil of war. These are the three things that I want to deal with today. Now let us turn first to the evil of racism. There can be no gainsaying of the fact that racism is still alive all over America. Racial injustice is still the Negro’s burden and America’s shame. And we must face the hard fact that many Americans would like to have a nation which is a democracy for white Americans but simultaneously a dictatorship over black Americans. We must face the fact that we still have much to do in the area of race relations.

Now to be sure there has been some progress, and I would not want to overlook that. We’ve seen that progress a great deal here in our Southland. Probably the greatest area of this progress has been the breakdown of legal segregation. And so the movement in the South has profoundly shaken the entire edifice of segregation. And I am convinced that segregation is as dead as a doornail in its legal sense, and the only thing uncertain about it now is how costly some of the segregationists who still linger around will make the funeral. And so there has been progress. But we must not allow this progress to cause us to engage in a superficial, dangerous optimism. The plant of freedom has grown only a bud and not yet a flower. And there is no area of our country that can boast of clean hands in the area of brotherhood. Every city confronts a serious problem. Now there are those who are trying to say now that the civil rights movement is dead. I submit to you that it is more alive today than ever before. What they fail to realize is that we are now in a transition period. We are moving into a new phase of the struggle. For well now twelve years, the struggle was basically a struggle to end legal segregation. In a sense it was a struggle for decency. It was a struggle to get rid of all of the humiliation and the syndrome of depravation surrounding the system of legal segregation. And I need not remind you that those were glorious days. We cannot forget the days of Montgomery, when fifty thousand Negroes decided that it was ultimately more honorable to walk the streets in dignity than to accept segregation within, in humiliation. We will not forget the 1960 sit-in movement, when by the thousands students decided to sit in at lunch counters, protesting humiliation and segregation. And when they decided to sit down at those counters, they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream and carrying the whole nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in the formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. We will not forget the Freedom Rides of sixty one, and the Birmingham Movement of sixty three, a movement which literally subpoenaed the conscience of a large segment of the nation to appear before the judgement seat of morality on the whole question of civil rights. We will not forget Selma, when by the thousands we marched from that city to Montgomery to dramatize the fact that Negroes did not have the right to vote. These were marvelous movements. But that period is over now. And we are moving into a new phase.