Message of the Day: Human Rights, Economic Opportunity, War, Hunger, Disease, Population, Enviroment, Personal Growth

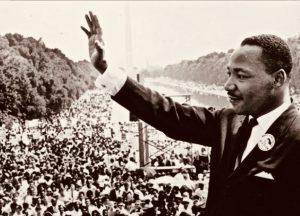

Martin Luther King, Jr. August 28, 1963, Smithsonian

Fifty years ago today, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated.

As we predicted last week, there has been a fair amount of coverage as the day came near and arrived, but virtually nothing compared to what should and would have happened in any normal universe.

And of course, most coverage, as we’ve been commenting on for many years along with a handful of others compared to the majority of commentary, avoids the core of what King stood for. Radical revolution to create a world in which there was equality for all, guaranteed by right and policy. An end to classism, racism, poverty, war. Basic needs and rights for all. No sentiment of equality, but a demand and a reality of equality by social contract, legal right, political and economic policy.

It would mean the entire world order turned on its head.

As we noted in the following excerpt from our post on 7.18.17:

“50 years ago, 1967, was the year the storm clouds gathered in a new way. And the storm began to break out in a new way. Then, 1968. And by the end of that year, nothing was ever the same again.

A 50th anniversary has just passed that needs more attention.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech at Riverside Church. The most important, most prophetic speech he ever gave.

One year to the day before he was killed.

It set the world on fire at the time. Rejected by many who had supported him. Then within a short time after he was killed, virtually universally praised as his penultimate call to accountability for every individual and for all humanity.

And then, for some time now, the most avoided speech he ever gave by many.

How is that possible?

Who does the US have national holidays for in their name?

One person.

Even Washington got morphed into President’s Day (Lincoln too as part of this, although he never had a federal holiday)–and how many now even know the origin of that?

Even Jesus, who has Christmas, isn’t the center in practice of the holiday of his birth in the US (and many other places.) The “Christ” in the holiday name would seem to be clear–but for separation of church and state reasons in the US, because the churches are less and less attended, and because the holiday was utterly taken over by consumerism driven by emotion-targeted advertising long ago, the name of the holiday is more an echo of its origin than not.

One person has a national holiday in the most powerful nation in the history of the world named after him.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

He didn’t necessarily deserve it more than some of his allies and contemporaries, not to mention those who came before. He treated women as sex objects at times at the further expense of his wife and family. He was sexist and homophobic with some of his closest allies who made the movement and made him possible in many ways. He also associated with the above at a level many didn’t at the time. And no one who was out front on the principles he was would have failed to move past the above limitations as the culture did after he died in no small part because of the principles he died for.

In any event, he’s got the holiday. The only one who does.

So how do we avoid the greatest call to accountability ever from the prophet we gave this unique position?

Because it was the holler of truth that went way past discomfort–it called (and calls) everyone to accountability with no veneer. We Americans especially. Although it was about his opposition to the Vietnam War, it wasn’t because he would never advocate fighting–he did against Hitler days before he died, as we’ve noted before. And his call for and acknowledgment of world revolution wasn’t naive. He hoped to avoid violence as much as possible by calling the greatest purveyors of it to account. But he understood just violence if unavoidable. Further he, and Alice Paul and Gandhi all knew well that non-violence was also a purposeful strategic provocation of violence as needed to achieve justice. It was all the unjust and unnecessary violence that King railed against in his Riverside speech opposing the Vietnam War. Especially what it did to children.

Riverside 1967 was an anti-war speech for all times. About a war and a time that was tearing America apart as nothing had since the Civil War. But it was about something much bigger. It was about the future of humanity, if there was to be one. Which if there was to be, must be free of racism and greed and exploitation and poverty and hunger–must mean equality for all. He had preached this for a long time. He had praised the democratic Scandinavian models for instance that provided all basic needs for all people. But he was going further now. Going global. A different globalism than the one he condemned that was in place even then.

Many have commented on the speech and its majesty. And on the hypocrisy of drowning out the real King and his increasingly angry and radical message, a further evolution of his showing the fullness of what love and justice really mean–as all truth-tellers like him have done. Many have called out the co-opting of the King brand to avoid the real message on the holiday. Of trying to focus on the dream speech (also avoiding its ultimate radical message) as a feel-good drug to misdirect from the very principles in the speeches. Because that would mean changing everything. Starting with our own lives.”

We went on to post the article on the 50th anniversary of the speech, by Benjamin Hedin, in The New Yorker: “Martin Luther King Jr’s Searing Anti-War Speech, Fifty Years Later”. As we said then; “There are no adequate superlatives of necessity to read it, again and again..”

Today, in The Guardian in London, Gary Younge writes the following in an indispensable article, “Martin Luther King: how a rebel leader was lost to history”:

On 15 January 1998, what would have been Martin Luther King’s 69th birthday, James Farmer was awarded the presidential medal of freedom in the White House’s East Room. “He has never sought the limelight,” said the then president, Bill Clinton. “And until today, I frankly think he’s never got the credit he deserves. His long overdue recognition has come to pass.”

Farmer, who ran the Congress of Racial Equality and led the Freedom Rides through the segregated south in 1961, was by that time blind, diabetic and a double amputee. He died the following year. When I spoke to him a few months after the ceremony, he said it was the best day of his life. “It was just like the old days. But this time, I felt like I was finally being vindicated; that the years of invisibility were over.”

And what, I asked, had rendered him invisible? Having a white wife, he said, had been an issue. But the main reason, he believed, was that the US had only enough room to remember one civil rights leader. “I was in the shadow of Martin Luther King,” he told me. “And that was quite a big shadow. It was King who made the ‘I have a dream’ speech. And King was assassinated – and that always enlarges a person’s image.”

In so doing they will wilfully and brazenly omit the fact that before his death in 1968, King was well on the way to becoming a pariah. In 1966, twice as many Americans had an unfavourable opinion of him as a favourable one. Life magazine branded his anti-Vietnam war speech at the Riverside church, delivered exactly a year before his assassination, as “demagogic slander”, and “a script for Radio Hanoi”. Just a week before he was killed, he attended a demonstration in Memphis in support of striking garbage workers. The protest turned violent and police responded with batons and teargas, shooting a 16-year-old boy dead. The press and the political class rounded on King. The New York Times said the events were “a powerful embarrassment” to him. A column in the Dallas Morning News called King “the headline-hunting high priest of nonviolent violence” whose “road show” in Memphis was “like a torchbearer sprinting into a powder-house”. The Providence Sunday Journal called him “reckless and irresponsible”. He was back in Memphis supporting the strike when he was killed.

Half a century after King’s assassination, there is value in reflecting on that shadow. The angle at which King’s body of work caught the light after he was killed tells us a great deal about how a black radical preacher came to be so big and what else may be hidden in the darkness.

This week, the US will indulge in an orgy of self-congratulation, selectively misrepresenting King’s life and work, as if rebelling against the American establishment was, in fact, what the establishment has always encouraged. They will cite the “dream” speech as if it were his only one – and the line about wanting his children to be “judged not by the colour of their skin but the content of their character” as if it were the only line in it.

This was the last time King received national coverage when he was alive, and so he died a polarising and increasingly isolated figure. Just six days after his death, the Virginia congressman William Tuck blamed King for his own murder, telling the House of Representatives that King “fomented discord and strife between the races … He who sows the seed of sin shall reap and harvest a whirlwind of evil.”

But in the intervening decades, the mud slung at him has been cleaned off and his legacy shined to make him resemble a national treasure. In the two years before his death, he did not appear in the Top 10 of Gallup’s poll of most admired men of the year. In 1999, a Gallup poll of the most admired people of the century placed him second behind Mother Teresa. In 2011, King’s memorial was opened on the National Mall in Washington DC, with a 30ft statue sitting on four acres of prime historic real estate: 91% of Americans (including 89% of white people) approved. Even Donald Trump has thus far refrained from besmirching his legacy, hailing just a few months ago King’s “legacy of equality, justice and freedom”.

The process by which King went from ignominy to icon was not simply a matter of time and tide eroding ill feelings and painful memories. “History” does not objectively sift through radical leaders, pick out the best on their merits and then dedicate them faithfully to public memory. It commits itself to the task with great prejudice and fickle appreciation in a manner that tells us as much about historians and their times as the leaders themselves.

“The facts of history never come to us pure,” wrote EH Carr in his seminal essay The Historian and His Facts. “Since they do not and cannot exist in pure form: they are always refracted through the mind of the recorder … History means interpretation … It is the historian who has decided for his own reasons that Caesar’s crossing of that petty stream, the Rubicon, is a fact of history, whereas the crossing of the Rubicon by millions of other people before or since interests nobody at all.”

Today’s understanding of King is the result of a protracted struggle and strategic reckoning involving an ongoing national negotiation about how to understand the country’s racial narrative. White America did not make the journey towards formal equality willingly. A month before the March on Washington in 1963, 54% of white Americans thought the Kennedy administration “was pushing racial integration too fast”. A few months later, 59% of northern white Americans and 78% of southern white Americans disapproved “of actions Negroes have taken to obtain civil rights”. That same year, 78% of white southern parents and 33% of white northern parents objected to sending their children to a school in which half the students were black. According to Gallup, it was not until 1995 that a majority of white US citizens approved of marriage between black and white people.

To discount King would be to dismiss the most prominent and popular proponent of civil rights. That in turn would demand some other explanation as to how the US shed the stigma of segregation and imagined itself as a modern, nonracial democracy. For while the means by which codified segregation came to an end – mass marches, civil disobedience, grassroots activism – was not consensual, the country did reach a consensus that it had to end. But there was no plausible account for how they travelled from Rosa Parks to Barack Obama that does not have King front and centre, even if the gap between black and white unemployment is roughly the same now as it was in 1963, southern schools are resegregating and the wealth gap is widening.

So, white America came to embrace King in the same way that white South Africans came to embrace Nelson Mandela: grudgingly and gratefully, retrospectively, selectively, without grace or guile. Because, by the time they realised their hatred of him was spent and futile, he had created a world in which loving him was in their own self-interest. Because, in short, they had no choice.

“Our country has chosen the easier way to work with King,” the late Vincent Harding, who wrote a draft of King’s Riverside speech, told me. “They are aware that something very powerful was connected to him and he was connected to it.”

It has not been a straightforward journey for black America either. King was always popular with black Americans, though not always with black political leaders – younger activists mockingly referred to him as “de lawd” because he was so grand, while his contemporaries criticised him for parachuting in on conflicts to great media attention. But the victories for civil rights soon came up against the legacy of several centuries of oppression and the realities of capitalism. In short, what does racial equality look like in a country where economic inequality is deeply ingrained into the system – what is the value of being able to eat in a restaurant of your choice if you can’t afford what’s on the menu?

At a meeting in Chicago in 1965, King was shaken after he was booed by young black men in the crowd: “I went home that night with an ugly feeling, selfishly I thought of my sufferings and sacrifices over the last 12 years,” he recalled. “Why should they boo one so close to them? But as I lay awake thinking, I finally came to myself and I could not for the life of me have less than patience and understanding for those young men. For 12 years, I and others like me have held out radiant promises of progress, I had preached to them about my dream … I had urged them to have faith in America and in white society. Their hopes had soared. They were now booing me because they felt that we were unable to deliver on our promises. They were booing because we had urged them to have faith in people who had too often proved to be unfaithful. They were now hostile because they were watching the dream they had so readily accepted turn into a frustrating nightmare.”

So the King America has chosen to remember stands at Lincoln’s feet talking of a dream “deeply rooted in the American dream”. But by the long, hot summer of 1967, which saw riots in Newark, Cincinnati and Buffalo, and tanks rolling down the streets of Detroit, King had, in the midst of the cold war, moved on to questioning capitalism. “We must honestly face the fact that the movement must address itself to the question of restructuring the whole of American society,” he said in August 1967. “There are 40 million poor people here, and one day we must ask the question, ‘Why are there 40 million poor people in America?’ And when you begin to ask that question, you are raising a question about the economic system, about a broader distribution of wealth. When you ask that question, you begin to question the capitalistic economy … when you deal with this, you begin to ask the question: ‘Who owns the oil?’ You begin to ask the question: ‘Who owns the iron ore?’ You begin to ask the question: ‘Why is it that people have to pay water bills in a world that’s two-thirds water?’”

In 2002, when I first interviewed the late poet and author, Maya Angelou, about a volume of her memoir which covered the assassinations of King and Malcolm X, I asked what she thought they would be focusing on had they lived. My normally loquacious interviewee sat silent before shaking her head and releasing a long, helpless breath. “I can’t,” she said. “I can’t. So many things have happened since they were both assassinated. The world has changed so dramatically.”

Reputations forged in revolutionary periods can rarely be sustained through calmer times. In moments of social turmoil and sharpened conflict, the stage yields to the declarative, decisive, emphatic and bold; to those who can rally their own side and face down their tormentors. Revolutionary moments favour not just the single-minded but the reckless, which, in King’s case, meant a man who was prepared to wear his funeral clothes to work.

I once asked Jack O’Dell, one of King’s long-term aides, why King had delivered his speech about Vietnam when he knew it would ruin his relationship with the White House and cost the movement a lot of support and funds. “He had the Nobel prize,” said O’Dell, “and he didn’t know how long he was going to live. He wasn’t but 39, but he wasn’t going to live much longer, and that meant he didn’t have but maybe a few more speeches to give. So he had to say what he was going to say.”

But once the conditions that make those periods possible evolve, so do the leadership skills necessary for the new moment. Those who are most effective at the barricades aren’t necessarily best equipped for the boardroom, which is why the transition from guerilla to government is so fraught for so many movements. That evolution never stops.

So Jesse Jackson, who was with King in Memphis the day he died, reinvented himself as an electoral contender during the 80s, channelling the spirit of the civil rights movement into a broad-based coalition embracing unions, feminists, gay rights activists and environmentalists that posed a challenge to the Democratic party. But, 20 years later, he was heckled by black protesters against police brutality in Ferguson, Missouri. In her memoir, When They Call You a Terrorist, one of the Black Lives Matter founders, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, berates those “black pastors and then the first black president [who] preached [about personal responsibility] more than they preached a commitment to collective responsibility”.

And many turn the pages of history quicker than they can read, let alone understand them. John Lewis, the sole living speaker from the March on Washington in 1963, questioned Trump’s legitimacy given the alleged involvement of Russia in the election. Lewis, who was bludgeoned by bigots in Birmingham, Alabama in 1961 and by police in Selma in 1965, was criticised by Trump on Twitter in January last year for being “all talk, talk, talk – no action, no results”.

So in life, King’s one-time contemporaries struggle, as he did, with a white America that is dismissive and a black America that demands more than their movements can deliver. In death, the struggle is to ensure that King’s legacy isn’t eviscerated of all militancy so that it can be repurposed as one more illustration of the American establishment’s God-given ability to produce the antidote to it’s own poison.

This contradiction was most blatant in February, during the Super Bowl, when Ram trucks used a recording of a sermon King delivered about the value of service to sell its product – “Built to serve”.

[We take a brief interlude here from Younge’s piece today to an excerpt from our own post on the above on 2.10.2018:

“The Super Bowl itself is an archetypal modern example of the gladiatorial using and destroying of humans by humans for mass human entertainment from projected individual and tribal aggression to extraordinary performance to emotional manipulation (well, then there’s the Olympics–sexually abusing and in every other way using and abusing children and adults in service of the same, as we, Bryant Gumbel on “Real Sports” and many others have been expressing for some time–but at least this year the peace fakery may possibly have some real impact). In a hopeful sign, the pro-football audience is waning (although still huge) and parents increasingly refuse to send their boys to the slaughter of the farm leagues. Boys who are abused physically and psychologically by the process and are taught violence and power are a requirement of self-worth (the whole culture teaches these things), while girls are taught to enable this and seek power by being sex objects on the sidelines (the culture teaches this too, and that women seeking power should emulate the above, exemplified by adult women increasingly screaming for blood on the field as loudly as anyone).

So, what follows is a Rorschach test of your basic sense of awareness and conscience. And a wakeup call of a scream through the ages.

One of the hallmarks of the Super Bowl is that it’s also the Super Bowl of advertising–that medium generally used to feed every most base impulse we have to consume.

So, we’re watching, live, as monitoring media and culture is a critical part of our work, which public service advertising has also been a critical part of.

The image is of a Dodge Ram truck. The voiceover sounds so familiar. But its instantly brain-exploding and you don’t at first know why.

NO! That is NOT the voice of Martin Luther King, Jr.!

NO! that is NOT his famous “The Drum Major Instinct” speech of exactly 50 years before to the day!

NOT at the start of this 50th anniversary year of that year of years in the US and around the world–Vietnam (this is the 50th anniversary of the second week of the Tet Offensive) and Civil Rights and King and Kennedy and on and on–1968.”

We then referred to, among other commentaries, Younge’s excellent article then, “Big business is hijacking our radical past. We must stop it”. Now back to today’s commentary.]:

The insult to King’s memory could not have been more absolute. In another part of the sermon Ram used, King literally tells the congregation not to be fooled into spending more money than necessary on cars by sharp advertisers. “These gentlemen of massive verbal persuasion,” he says, “have a way of saying things to you that kind of gets you into buying … In order to make your neighbours envious, you must drive this type of car … And before you know it you’re just buying that stuff.” In a week that will see almost every stratum of American society – the society that voted for Trump – mourn King’s passing and hail his contributions, this may well be the most important message of all.

This article includes material excerpted from Gary Younge’s book, The Speech: The Story Behind Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s Dream

Linked are many other articles, such as Michael K Honey’s, “Martin Luther King’s forgotten legacy? His fight for economic justice”:

“King early on described himself as a “profound advocate of the social gospel” who decried a capitalist system that put profits and property rights ahead of basic human rights. Beyond his dream of civil and voting rights lay a demand that every person have adequate food, education, housing, a decent job and income.”

And Cornel West’s, “Martin Luther King Jr was a radical. We must not sterilize his legacy”:

“The major threat of Martin Luther King Jr to us is a spiritual and moral one. King’s courageous and compassionate example shatters the dominant neoliberal soul-craft of smartness, money and bombs. His grand fight against poverty, militarism, materialism and racism undercuts the superficial lip service and pretentious posturing of so-called progressives as well as the candid contempt and proud prejudices of genuine reactionaries. King was neither perfect nor pure in his prophetic witness – but he was the real thing in sharp contrast to the market-driven semblances and simulacra of our day.”

And video of King’s last public appearance the night before he died, the last part of his last speech that displays a kind of proof of God–in the sense that believers to atheists alike can understand. A sick man rousted from his bed to speak to those who waited to hear him–and whose body, heart and mind converge in all the power a human can muster to evoke or create the eternal: ” ‘I’ve been to the mountaintop’: an excerpt from Martin Luther King’s final speech”.

There are no more words after seeing this, fifty years ago last night. The last night Martin Luther King, Jr. was on this earth with us.

- “UN inquiry finds Russia’s deportations of 20,000 Ukrainian children amounts to crimes against humanity “, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Reuters

- “Brooks and Capehart on Trump’s decision to launch strikes on Iran”, PBS NewsHour

- Issue of the Week: War

- “The Original”, The New Yorker

- “Big Change Seems Certain in Iran. What Kind Is the Question”, The New York Times

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017