Message of the Day: War, Human Rights, Economic Opportunity, Disease, Hunger, Population, Environment, Personal Growth

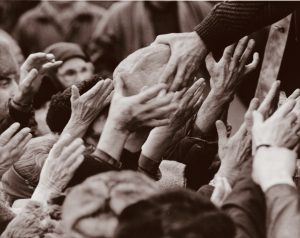

Bread, land & peace, Russia 1917 (c) 1996-2018 Planet Earth Foundation

We left the post up on the 50thanniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., since April 4 until today. The point of doing so was made in the post itself.

Now, time to move on.

There are always too many issues to cover. But it became self-evident tonight what needs to be focused on.

The Showtime series, “The Circus”, has resurfaced one year after it’s extraordinary first two seasons covering the US presidential campaign and first few months of the Trump presidency, appropriately revamped. Mark Halperin, accused of sexual harassment by multiple accusers last October, is gone. Joining John Heilemann and Mark McKinnon is Alex Wagner, an excellent veteran journalist and a woman of color—a most welcome and noteworthy change.

The Circus has a new tagline, “Inside the Wildest Political Show on Earth” replacing “Inside the Greatest Political Show on Earth”, reflecting probably the change in commentators, since the second season covered the post-election period after the inauguration just as season three now picks up on. (It may also have reflected the change in context since the great majority of episodes were during the campaign followed by a short period after the innuguration). Season one covered the campaign in 26 amazing episodes. Season two had only 9 episodes from March to May last year.

We’ve commented since the election on what has been widely said, again and again—the noise in the political universe has risen to a new, in some ways indescribable level. It’s often simply too much for the human body, mind and soul to absorb—partly by intention and partly as a natural consequence of events in a new level of the toxic grinding stage of evolution we are in.

Let’s just say that the first episode of “The Circus” tonight was both revelation and relief. And absolutely necessary.

It covers the first week of April through the Syrian chemcial attacks on children, women and men civilians, and retaliatory strikes on Syria Friday by the US, UK and France.

The centers of coverage the reporters go to are Washington, D.C, Moscow and London. The interviews are—and the access is—astounding.

Somehow, these reporters manage to cover all the major issues over the past two-weeks, with the historic background since the Trump election and before, in half an hour at hyper-speed, that made all the noise and background make sense.

Honestly. Best brief, deep dive on Trump, Putin, US, UK, Russia, Syria, Facebook, Internet wars, new cold (and hot) wars and—kind of, sort of—everything else.

Wagner has brought a vastly improved chemistry and intelligence to the series—imagine that.

And the thing is—the series was already great.

Here’s an excerpt from our post on November 15, 2016:

“It has been a week to the day since the US presidential election. The shock and aftershocks of the earthquake that occurred that day continue to reverberate for probably everyone, regardless of views.

For the first time in broadcast history, a real-time documentary series has been airing on Showtime since the start of the primaries, titled, “The Circus: Inside The Greatest Political Show On Earth.”

The on-camera presenters who follow the campaigns from the inside and the outside are Mark Halperin, John Heilmann and Mark McKinnon. Despite the significant usual flaws of the journalists being white male-dominated (per the above) and covering the ‘show’ more than the substance—given the credentials and intelligence of the presenters, and given the tragic fact that show over substance has been the increasing reality for sometime in these campaigns, the unvarnished cinema-verite experience of everyone involved, from candidates to other journalists to voters and more, is astonishing.

Particularly astonishing, astounding, agonizing, singular, historic, seemingly impossible—is the real-time experience of the just concluded events of the campaign’s last few days, the election, and the aftermath, in the special one-hour season finale, ‘President Trump.’ The experience of the finale episode unfolds exactly as most people experienced it–no one expected the title of the finale to be the above. And that includes the presenters. There are some real-time rants and wisdom as could only have been created by this experience as it happened.

Take a last ride on the ride we all just took. It’s worth it. Really. Really. Don’t miss it.

We recommend the whole series. But if you’re not up for or able to do that–just watch episode 26, the season finale, which aired for the first time Sunday, with footage from up to just two days before airing.

The finale stands alone–you don’t need to see a thing before it. And because it’s just days away from an indescribable experience for all of us, there is something incomparable about watching it right now for which further words have no utility. Even if you watch the whole season, this is one time where the only place to start is with the finale–right now.

Go to the Showtime site. It is airing again this week (look at Showtime for dates and times), or stream it starting 30 seconds from now. Just make sure you’re in a no distraction time and space zone for the hour, which seems like a second, which seems like eternity.”

A year later, after the short second season, “The Circus: Inside the Wildest Political Show on Earth” has arrived none too early for us, yet perhaps perfectly timed.

In 30 minutes your mind is cleared, blown and you get it. And it’s a little slice of paradise to know that there’s a good chance for this to be a weekly reprieve of illumination—that you can not only look instead of looking away, but will be exposed to the building blocks of reality that have seemed so elusive. Damn intelligent and damn entertaining (in the healthy sense).

Just go watch it. 30 minutes, just 30 minutes—brilliantly paced. And check into some non-toxic experience of what we all need to know because what happens still does and always will depend on all of us.

We’re not advertising for Showtime any more than we do for anyone. But if it costs something—and it may not depending on options available, it’s worth it regardless of any of the other great to cultural junk options on Showtime.

Just go watch it: “The Circus: Inside the Wildest Political Show on Earth”

Meanwhile, we share an excellent article from The Los Angeles Times yesterday interviewing Alex Wagner, the political/cultural moment that brought her to this new job, her fascinating history and her views on the show and the issues involved:

“Alex Wagner joins ‘the most ambitious television program on the air,’ Showtime’s ‘The Circus’”

By Meredith Blake, April 14, 2018

“Alex Wagner grew up immersed in politics in Washington, D.C., where her late father, Carl Wagner, advised such Democrats as Bill Clinton and Ted Kennedy. As she recently recalled over a pot of ginger tea, he’d sit by the phones at night waiting for poll numbers, answering calls with a gruff ‘Give me the numbers!’

But she followed a circuitous path to political journalism. In her 20s, she focused on music, working as editor of the hipster magazine the Fader, but in 2007 the so-called Saffron Revolution in her mother’s native country, Myanmar, stirred a desire to be ‘more engaged with the world.’

After stints as executive director of George Clooney’s anti-genocide organization Not On Our Watch and a White House correspondent for Politics Daily, in 2011 Wagner landed her own MSNBC show, ‘Now With Alex Wagner,’ despite being a TV newbie. ‘We had no idea what the hell we were doing,’ she said of the show, canceled in 2015. ‘But I probably had some success in my career because I haven’t overthought it and I’ve been like, well, we’ll figure it out.’

The 40-year-old is keeping busy with two new projects arriving this month. Beginning Sunday, she’ll join John Heilemann and Mark McKinnon as a co-host on the third season of ‘The Circus,’ replacing Mark Halperin, who was accused of sexually harassing multiple women during a previous job at ABC. Wagner considers ‘The Circus,’ Showtime’s behind-the-scenes political docuseries, ‘the most ambitious television program on the air.’ She’s also got a memoir, ‘Futureface: A Family Mystery, an Epic Quest, and the Secret to Belonging,’ exploring her mixed-race identity and complicated ancestry.

There’s so much news out of Washington these days. What story lines do you think you’ll be following closely this season on ‘The Circus’?

The Mueller investigation is huge. It could refashion the landscape of American politics in ways that no one can imagine. Or it could be nothing. The midterms could be the most consequential election of my lifetime in terms of the implications of what happens if the Democrats take back the House or Senate. And I’m really interested in the grass roots, what’s happening with Trump’s base, what’s happening with the Democratic base. We know there’s a historic number of women running. And even what we’ve seen in the wake of Parkland, how young people are really engaged and maybe reshaping dialogues we thought were long since established.

You appeared in a few episodes of ‘The Circus’ during the presidential campaign. What appealed to you about joining the show full time?

It’s important to get out into the field and not only talk to voters but see how the campaigns operate. As someone who sat in the anchor chair for a number of years, it’s a whole different experience and a whole different muscle group. The few weeks I was on the road with ‘The Circus’ were really illuminating and I think absolutely made me a better journalist. The Trump presidency is like nothing we’ve ever seen before. It feels really urgent. So it was not a hard sell to ask me to come on to co-host. I’m very worried about the sleep that I’m going to miss and the fact that I have an 8-month-old [son, Cy] at home. Mr. Mom, my husband [former White House chef Sam Kass], will be playing a large role.

You are one of several women in the news media taking over for men accused of misconduct. How does it feel to be part of this bigger change? Do you feel like this show in particular will benefit from your perspective?

I think having a diverse set of voices is always good. I think gender is on the frontburner in a way it hasn’t been ever. It’s great they’re bringing a woman of color into the show. I certainly never watched the show and said they’re missing a critical piece, but I think it’s fantastic they’re broadening their talent. As to the large question of this #MeToo moment, it is unfortunate that the circumstances had to be what they were to bring this moment about, but I’ll take change in whatever package that comes in. It’s unfortunate it has to be a result of what it was, but right on to my fellow sisters.

Your predecessor, Mark Halperin, and other members of the political press were criticized for what some saw as sexist coverage of Hillary Clinton during the campaign. Do you think that’s fair?

I think when you have an industry that is overwhelmingly dominated by one gender and one race, there is necessarily going to be bias whether intentional or unintentional. I don’t think there was malice, necessarily, but politics is a story and one’s interpretation of that story is informed by one’s background. And Hillary Clinton was a first. She was the closest a woman has ever come [to the presidency]. I think there was a lot of expectation. There was a lot of baggage. We probably should have been asking ourselves more pointed questions. Is the coverage fair? Are we paying enough attention to the gender dynamics here? We need to be more inclusive. Not just because it feels good, but the coverage will be better and the fourth estate will benefit overall.

What inspired you to write ‘Futureface’?

It was borne out of this existential loneliness that I felt as a child. I remember most of my childhood as sitting by myself playing solitaire, listening to Starship on the radio. I think I grew up with this sense that I was alone in the world and I think a lot of my adult life has been a search for community. As a mixed-race kid and only child, the question of identity when you don’t look like anybody else is sort of fraught. This was my attempt to find my people and unpack the story that had been handed down to me. My father was this devout Roman Catholic and about midway through this research I was at a family reunion paddleboarding on a lake with my cousin and he said, ‘Well, you know we’re Jewish, right?’ It was this drop-the-mic moment. Anybody who gets into the story of where you came from will inevitably find snags. This is is me pulling at those snags.

Your mother’s family’s story also turns out to be more complicated than you thought.

The Burmese Rohingya crisis has been an unfolding slowly for a number of years. My mom is a practicing Buddhist, I always thought how could it be possible that a Buddhist country could be doing this to its own citizens. Then I started to do research into my own family and started to better understand Burmese nationalism. We traditionally understand the old world in these glowing romanticized terms. I felt like it was really important to explain that things weren’t halcyon, perfect, rose-tinted, that there were very real problems that were left behind that have very real consequences in the modern era, and that nationalism and tribalism isn’t unique to this particular moment, but it is something that has plagued countries and families around the world. We’re all a little bit broken in some way, and that’s unifying in some way in and of itself.

Do you feel like you learned a lot about yourself or your family in the process of writing the book?

Yes, and I learned more about this country too. My father said growing up in Iowa in a northeast town on the Mississippi River, there were no people of color. I had accepted that unquestioningly; it’s just Iowa. But then you begin to think, why weren’t there people of color? Part of the reason is we drove the people of color who originally owned the land off the land and we prevented other people of color from coming to the country. When his people went over there in the 1850s, the Winnebago had just been kicked off the land. And it’s just not something that ever intersected with my family’s story. These are really simple truths that are readily accessible and yet nobody actually tries to find them or dig deeper into them.

Is there anyone in politics you’re dying to interview for ‘The Circus’?

Steve Bannon. There are a lot of parts about Steve Bannon that are worthy of investigation, but he has a sixth sense for American politics and it is borne of deep conviction and philosophy. I always want to interview John Boehner. Especially now where he’s just drinking merlot and smoking. He’s a fascinating figure in American politics. He represents the split of the old Republican party with the new. And Melania. Knowing I’ll never get it, but she has an incredible story. Someday, I hope she’ll tell it — to me, or anybody. There’s a lot to unpack there.”

In conclusion, we re-post a major piece from last October 17. It began with a real-time reveiw of the events that led to the context that Wagner refers to which led to her new role on “The Circus”. And many other critical events unfolding at the time.

But primarily focused on an article on the 100th aniversary of the Russian Revolution–the most informitive and engaging piece you could ever hope to read as the headline article for The Smithsonian magazine. One of the most important events in history that continues to play out in Russia and around the world today, and that instructs the strategies of Putin to Trump to this day.

It also points out the status of a world more exposed than ever to explosion based on the extreme inequality or lack of a sustanibale environment that always leads to it.

Consider these excerpst from the end of the article:

“One simple lesson of the revolution might be that if a situation looks as if it can’t go on, it won’t. Imbalance seeks balance. By this logic, climate change will likely continue along the path it seems headed for. And a world in which the richest eight people control as much wealth as 3.6 billion of their global co- inhabitants (half the human race) will probably see a readjustment. The populist movements now gaining momentum around the world, however localized or distinct, may signal a beginning of a bigger process. …

Unlike Marxism-Leninism, Lenin’s tactics enjoy excellent health today. In a capitalist Russia, Putin favors his friends, holds power closely and doesn’t compromise with rivals. In America, too, we’ve reached a point in our politics where the strictest partisanship rules. Steve Bannon, the head of the right-wing media organization Breitbart News, who went on to be an adviser to the president, told a reporter in 2013, “I’m a Leninist…I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy today’s establishment.” Of course he didn’t mean he admired Lenin’s ideology—far from it—but Lenin’s methods have a powerfully modern appeal. Lenin showed the world how well not compromising can work. A response to that revolutionary innovation of his has yet to be figured out.”

Here’s the post:

10.17.17:

Yesterday was World Food Day.

To that in a bit, and the diving deeper on hunger and related issues promised in the post on the solstices and The New York Times editorial on world hunger.

First, a quick notation on the Hollywood cesspool of sexual assault and enabling emerging around mogul Harvey Weinstein, prevalent in the news in the US for the past couple of weeks. On the former, as in all systems, much more to come from many quarters, to be sure. The latter appears to involve almost everyone, right up the political food chain, in an enmeshed level of hypocrisy difficult to overstate.

What perfect horrible poetic justice that Ronan Farrow brought the above story to a more serious level (after The New York Times broke the story) in The New Yorker after being jammed by NBC. He previously backed his adopted sister’s allegations of child rape at age seven against his father, Woody Allen (not prosecuted because of trauma to the child) who also started a secret sexual relationship with another adopted sister (at 19 or thereabouts—age uncertain) while in a long-term relationship with the adoptive mother, then married the adopted daughter later and described the benefits of his paternal role in their marriage in an NPR interview. And the all-Hollywood, all the time rage, formerly led by current perp number one (and many of those now on take-down patrol of him, some only after a prolonged deafening silence) demanding that an admitted and convicted oral, vaginal and anal rapist of a 13-year old, Roman Polanski, be let off the hook. It just keeps spreading in all directions. Just read up, and keep following the trail. Whether or not underage victims emerge in the Weinstein scandal (not clear as we write), he was the bishop enabler of child abusers in Hollywood.

As we write, The Daily Beast reports: “Actress Evan Rachel Wood tweeted Tuesday that pedophilia in Hollywood ‘will be the next dam to break’.

And from a piece in The Guardian on the Weinstein scandal comes this:

“’Sex abuse in Hollywood required wider complicity than abuse in the Catholic church, said Lorien Haynes, a Los Angeles-based writer who worked on An Open Secret, a documentary about abuse of underage boys. ‘It’s even a little more insidious with Hollywood because men and women are involved.’”

No society, civilization or species that doesn’t protect its children first and foremost, will protect anybody. Abuse of children is in a league of its own as the worst evil there is—normal people say this instinctively. Even child abusers and their enablers usually mouth this, while they hide their own actions, and consider the worst abuse to be any revelation of the secret that holds them accountable—or any withholding of interaction with their life-long recovering victims, depriving them of their sense of control and security, but necessary for survivors to have the possibility of ongoing recovery. Power over children who are supposed to be the first responsibility to nurture is absolute. Their abusers expect a lifetime of compliance with rape, torture, and systemic enabling, consciously or unconsciously.

No justice or protection for adult victims of sexual assault will happen on a meaningful scale if it hasn’t happened for children.

Another story from India, an historic leap forward in protection from child rape, impacting millions (receiving only fleeting global coverage all too typical for mainly poor girls of color in the developing world) in the nation about to become the largest on earth, was of extraordinary consequence, and should have been a global headline, discussion and action catalyst for some time.

Here’s Bhadra Sinha of Hindustan Times, New Delhi last week:

“A man can be charged with rape if he has sex with his underage wife, the Supreme Court ruled on Wednesday, a landmark order that removed discrepancies in various statutory laws to fix the age of consent at 18.

The court was hearing a petition that sought scrapping of a provision in the rape law that allowed a man to have sex with his underage wife without her consent.

A bench of justices MB Lokur and Deepak Gupta said a girl child “cannot be treated as a commodity having no say over her body or someone who has no right to deny sexual intercourse to her husband”.

It ruled that a man can be prosecuted if his underage wife registers a complaint within a year of the offence.

The verdict is likely to be a deterrent against child marriage, which is illegal in India but common in poor communities where a girl is seen as a financial burden.

‘This would compel families of boys to think twice before getting their sons married to minor girls,’ said advocate Gaurav Agarwal, the counsel for Independent Thought, an NGO on whose petition the court gave its judgment.

The order brought the rape law in harmony with all special legislation meant to protect children.

Rape and child marriage laws in India disagreed on the age of consent. Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code says sex with a girl below 18 is rape, but it makes an exception that allows a man to have sex with his underage wife, 15 or above, even without her consent.

The provision was contrary to the child marriage law that sets the legal age for matrimony at 21 for men and 18 for women.

The top court read down the exception, calling it arbitrary, whimsical and capricious.

‘It violates the right to fair treatment of the girl child, who is unable to look after herself,’ it said.”

A recent study from census data showed 12 million children under 10 years old married, 65% girls, but also many boys. The Women and Child Development Ministry has acknowledged that recent data available shows 43 per cent of girls married before the age of 18.

BBC News reported:

“This is a landmark judgement that corrects a historical wrong against girls. How could marriage be used as a criterion to discriminate against girls?” Vikram Srivastava, the founder of Independent Thought, one of the main petitioners in the case, told the BBC.

However, the BBC’s Geeta Pandey in Delhi says that while welcome, the order will be difficult to implement in a country where child marriage is still rampant.

“Courts and police cannot monitor people’s bedrooms and a minor girl who is already married, almost always with the consent of her parents, will not usually have the courage to go to the police or court and file a case against her husband,” our correspondent says.

India’s government says the practice of child marriage is “an obstacle to nearly every developmental goal: eradicating poverty and hunger; achieving universal primary education; promoting gender equality; protecting children’s lives; and improving women’s health”.

India’s government has also acknowledged, as noted before, that half of India’s children are sexually abused.

Power and money, of course, as we’ve noted before, determine accountability more often than not. So, the New York prosecutor lets the Hollywood mogul off the hook (despite a recorded admission and the police certain of conviction on at least one degree) and the mogul pays off the accuser after a smear campaign against her—and now investigations are on again.

Because investigative journalism and resulting public outrage make a difference. Even if the money/power dynamics prevail again in this or other cases, the process of the arc toward justice is furthered.

Power, those who have it and those who don’t, in varying degrees, is at the root of everything in many ways. When we get to hunger and related issues below, this is a central theme.

By the way, still wondering how Trump got off the hook on the Hollywood Access tapes with enough voters to still win? We’ve covered that at length some time ago. But as Lizz Winstead, progressive feminist co-creator of The Daily Show, put it when interviewed with MSNBC’s Katy Tur last week, the Democrats aren’t credible now on this issue because of the Obamas and the Clintons silence for too long on their mogul friend and funder.

Great. Progressives destroying progressivism. But sexual abuse is not relegated to any political party—it’s relegated everywhere, and so are the consequences.

[A few weeks later on 11.21.17, we posted the following excerpt, after, among other things, numerous feminists and Democratic leaders, including Kirsten Gillibrand, who took over Hillary Clinton’s Senate seat when she became Secretary of State in 2009, said Bill Clinton should have resigned the presidency:

“The next historic explosion around issues of sexual harassment (often mis-defined in reporting), sexual assault (also often mis-defined or incorrectly conflated with the former in reporting), child sexual abuse (too often not reported clearly as its own most grievous distinction), gender, and ultimately power have been occurring with an exponential speed and force that make writing one second seem outmoded the next.

How impossible, it would have seemed, just a short time ago, that we would be looking at a reminder on our TV screen for an iconic talk show for decades, with no icon, not even a name, because the show went off the air last night, but the technology of reminding about fallen icons has not caught up.

Too many such examples to begin to cover. The gender inequality side of the issue will just keep marching on, as with all equality struggles, until equality is there. But no smooth trip.

The left is having a reckoning unlike before on this issue and many on the left are welcoming it, because if nothing else it can’t be avoided now, and the reckoning is necessary for the reckoning on the right, which is part of the necessary reckoning beyond such labels.”]

Speaking of Katy Tur, her recent appearance on Charlie Rose [no one knew at the time Rose was about to be removed from any journalistic presence because of numerous allegations of sexual misconduct per the 11.21.18 excerpt above] was a reminder and a revelation. Great journalism can be brought to us by the committed in spite of the wasteland they work in. And be objective in the main regardless of their politics. Tur has just released her book on the campaign as NBC’s reporter following Trump. The job of a lifetime, which she just fell into by accident. She became famous during the campaign when attacked by Trump during a rally, which risked the real possibility of physical attack by some in the crowd. Watch the segment, read the book. She also does a stand-up job with intellectual integrity and objectivity of describing for many of her (it seems doubtless) fellow liberals the reasons why Trump won that still seem to elude them. Which if it continues, will become an ongoing and escalated haunting.

The sideshow of Trump, the NFL and the national anthem are worth a comment. Trump won before he started—so far. Seventy percent of Americans already agreed with him—it only went down to fifty because it was him—but underneath it seemed a winner for him from the start. The flag and anthem represent enough to enough people, including many who voted against Trump, as to be problematic for most people when they appear dissed.

Of course, free speech and protest should be honored. But that protection under a business context may be more complex or it may be protected entirely (it should be in our view, and the players who choose to should continue, and the union and owners should support them). But this isn’t 1968 at the Olympics. Are the rich celebrity players giving most of their money to the cause they protest, and their time and energy?

That’s part of a public perception reality. Plus, this is a public that doesn’t really care about the players except as blood sport entertainers. This is the modern version of Rome circa Commodus. Read Frank Bruni’s excellent New York Times September 6 article, “Can We Talk About Tom Brady’s Brain?” The drumbeat of articles and actions to stop the virtual murder by football, increasingly from football lovers and participants, just keeps building. It was at a crescendo at the moment Trump changed the subject, as if on cue as a provocateur for fellow rich dude owners. And for himself, where a change of subject was desperately needed, and the convenient foil appeared.

“Are you not entertained?”, as Maximus taunted the crowd in “Gladiator”.

Following-up now on the last story we posted about, we kept up the Las Vegas post for two weeks.

Does anyone remember the worst mass shooting in US history, just weeks ago?

Just wondering.

Were new laws passed on gun control? Not in cowboy and cowgirl America.

Not enough slaughter still, not enough blood yet, after all these years.

Of course, worse slaughter everywhere as usual, Mogadishu, Iraq and on and on. Watch VICE news—go back and watch the whole year—leading up to the season ending segment on the Iraqi liberation of Mosul from ISIS. The most intense urban warfare since World War Two. And the aftermath of ISIS butchery, especially the impact on children.

ISIS appears finished—as the on the ground caliphate sweeping the region not long ago. But the underlying causes continue, ergo the danger.

Now Iraq (actually Iran) and the Kurds are at it. Iraq still exists in no small part because of the Kurds, instead of being part of the caliphate. The Kurds have been looking to independence since Saddam and before. Ask the Turks. Another place in depressing shape. Oh, and yes, Syria is still there even if you’re not paying attention to that blight on our humanity anymore.

Iran deserves approbation. A separate issue from the treaty depriving them of nuclear weapons, upon which rests any hope of preventing further proliferation and Armageddon. Hopefully the various members of the US administration dubbed the committee to save the republic (CSR) will keep the treaty in place agreed to by—the whole world—one of the rare times this has happened.

Then there’s the other nuclear problem. The real one. North Korea. When Nick Kristoff writes that after visiting what he describes as the worst totalitarian regime ever, while Trump-talk and tweets throw gas on the fire, it reminds him of what it was like when he went to Iraq on the eve of war, it makes you launch out of your chair and smash your head on the ceiling. Iraq would be a footnote compared to this. And the season-opening PBS Frontline (watch it) covers the same issue—Kim, the “let them eat nukes” brother-murderer, doing the sandbox tango with Trump. The situation is impossibly horrible no matter what choice is made. Having smart calm people making the choices would be helpful. Hopefully the CSR comprises this and holds sway. There also appear to be smart people in Beijing (Xi Jinping was just declared the most powerful person on the planet by The Economist—an overstatement with a purpose containing many elements of truth), but whether they will be smart in seeing the forest of their and everyone else’s self-interest from the anachronistic nationalist trees is in question.

Of course totalitarian communist North Korea and totalitarian communist, now capitalist, China, would not exist except for two things—hunger and poverty, and the Russian Revolution, the two things being intimately related.

The Russian Revolution, and specifically the Bolshevik October Revolution, one hundred years ago, are the lens through which we look at hunger and related issues here.

One hundred years ago, the hungry women of St. Petersburg took to the streets chanting one word, “Bread”. The date is celebrated as International Women’s Day still, as we’ve noted before.

But who knows it?

The women were joined on the streets by workers who walked out. To everyone’s shock, including the Bolshevik revolutionaries like Leon Trotsky.

Then the Czar’s soldiers joined them.

A revolution in days. The Czar was done. Women had the franchise. Democratic and revolutionary institutions were formed as transitionary mechanisms to ongoing democracy and equality. But the bread didn’t come fast enough, or changing the roots of the lack of it. So Vladimir Lenin’s and the Bolshevik’s slogan of “Bread, land and peace” had increasing resonance.

How is it possible to overstate the importance and historic impact of the Russian Revolution?

For a few short months it could have been the catalyst for the new world democratic socialists were fighting for. With the Bolshevik coup, it instead became probably the greatest murder machine in history. And at the end of World War Two, when the defeat of Hitler and fascism and the establishment of the UN and the beginning of the end of colonialism had the opportunity to create, again, a more cooperative equality on the planet— through a very challenging process but a real possibility—instead we got the Cold War, with the nuclear threat of the end of life on earth.

Hunger has been perhaps the number one symptom and the number one symbol of the lack of equality on earth through history. It still kills more people every year, mostly children, than anything, along with its companion disease and its underpinning of poverty. The struggle between those who have power and money at the expense of those who don’t has been the story of history, in which context everything else can be explained in many ways. The survival of most people throughout history in terms of basic needs has been threatened in varying degrees and they have been enslaved and oppressed in varying degrees, while a minority benefits. As the pressure mounts, and when it reaches extremes, it explodes. Out of this comes progress, then regression, then start again. Each step forward more promising, each step backward more extreme and dangerous. Human rights, war, hunger, disease, economic opportunity, environment, population, personal growth—all completely tied together.

Hence, now, one world, with the capacity to provide for all or to kill itself.

So, let’s look back at the Russian Revolution, the context before and the aftermath to this moment, and what lessons it has to offer.

In this month’s edition of Smithsonian Magazine, there is a truly magnificent long-form article on the issue, intellectually and emotionally stimulating, perceptive, compelling, enormously instructive and a read that utterly immerses the reader as if personally experiencing what is written—because the author both has this depth and breadth of knowledge and presents the material as part of his own personal experience.

Ian Frazier’s resplendent piece (accompanied by the stunning photography of Olga Ingurazova) is titled, “Whatever Happened To The Russian Revolution?”.

Frazier’s hero is the extraordinary journalist, author, activist and revolutionary, John Reed.

In The New York Times yesterday, in an Op-Ed about Reed, “The Journalist and the Revolution”, as part of the Red Century series commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution by Jack Shenker, journalist who covered the Egyptian revolt during the Arab Spring, he writes:

“And for the past century all of them [correspondent’s coverage of popular revolts], consciously or not, have been shaped to some degree by the work of John Reed, the legendary chronicler of Russia’s October Revolution in 1917.

Reed, a young American who arrived in Saint Petersburg with his wife, Louise Bryant, just as Russia’s fragile provisional government began to buckle and the city’s back streets were humming with whispers of strikes, mutinies and sedition, made no claims to impartiality in his coverage. ‘This was his revolution, not an obscure event in a foreign country,’ the British historian A.J.P. Taylor later wrote. Reed’s book, ‘Ten Days That Shook the World,’ explores the Communist insurgency not as a scientist might analyze slides through a microscope but rather as a lived experience, with all of a real life’s hopes and fears.’”

As we’ve noted before, the movie “Reds” does an astonishing job of covering this story and era and the eventual disillusionment of Reed and others with the Bolsheviks. (Some of the actors of both genders have a lot to answer for at least in enabling in various aspects of the current Hollywood scandal and related trails, and God knows what else to come, but the historical reality and importance of the movie needs to be acknowledged here.)

So, whatever happened to the Russian Revolution?

We know we say this a lot in one way or another. This can’t be missed. But it can’t be missed.

Here it is:

Whatever Happened To The Russian Revolution?

We journey through Vladimir Putin’s Russia to measure the aftershocks of the political explosion that rocked the world a century ago

By Ian Frazier

1

Russia is both a great, glorious country and an ongoing disaster.

Just when you decide it is the one, it turns around and discloses the other. For a hundred years before 1917, it experienced wild disorders and political violence interspersed with periods of unquiet calm, meanwhile producing some of the world’s greatest literature and booming in population and helping to feed Europe. Then it leapt into a revolution unlike any the world had ever seen. Today, a hundred years afterward, we still don’t know quite what to make of that huge event. The Russians themselves aren’t too sure about its significance.

I used to tell people that I loved Russia, because I do. I think everybody has a country not their own that they’re powerfully drawn to; Russia is mine. I can’t explain the attraction, only observe its symptoms going back to childhood, such as listening over and over to Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf,” narrated by Peter Ustinov, when I was 6, or standing in the front yard at night as my father pointed out Sputnik crossing the sky. Now I’ve traveled enough in Russia that my affections are more complicated. I know that almost no conclusion I ever draw about it is likely to be right. The way to think about Russia is without thinking about it. I just try to love it and yield to it and go with it, while also paying vigilant attention—if that makes sense.

I first began traveling to Russia more than 24 years ago, and in 2010 I published Travels in Siberia, a book about trips I’d made to that far-flung region. With the fall of the Soviet Union, areas previously closed to travelers had opened up. During the 1990s and after, the pace of change in Russia cascaded. A harsh kind of capitalism grew; democracy came and mostly went.

Then, two years ago, my son moved to the city of Yekaterinburg, in the Ural Mountains, on the edge of Siberia, and he lives there now. I see I will never stop thinking about this country.

As the 1917 centennial approached, I wondered about the revolution and tangled with its force field of complexity. For example, a question as straightforward as what to call certain Russian cities reveals, on examination, various options, asterisks, clarifications. Take St. Petersburg, whose name was changed in 1914 to Petrograd so as not to sound too German (at the time, Russia was fighting the Kaiser in the First World War). In 1924 Petrograd became Leningrad, which then went back to being St. Petersburg again in 1991. Today many of the city’s inhabitants simply call it “Peter.” Or consider the name of the revolution itself. Though it’s called the Great October Revolution, from our point of view it happened in November. In 1917, Russia still followed the Julian calendar, which lagged 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar used elsewhere in the world. The Bolshevik government changed the country to the Gregorian calendar in early 1918, soon after taking control. (All this information will be useful later on.)

In February and March I went to Russia to see what it was like in the centennial year. My way to travel is to go to a specific place and try to absorb what it is now and look closer, for what it was. Things that happen in a place change it and never leave it. I visited my son in Yekaterinburg, I rambled around Moscow, and I gave the most attention to St. Petersburg, where traces of the revolution are everywhere. The weather stayed cold. In each of the cities, ice topped with perfectly white snow locked the rivers. Here and there, rogue footprints crossed the ice expanses with their brave or heedless dotted lines. In St. Petersburg, I often passed Senate Square, in the middle of the city, with Étienne Falconet’s black statue of Peter the Great on his rearing horse atop a massive rock. Sometimes I saw newlyweds by the statue popping corks as an icy wind blew in across the Neva River and made the champagne foam fly. They were standing at a former pivot point of empire.

I’ll begin my meditation in 1825, at the Decembrist uprising. The Decembrists were young officers in the czar’s army who fought in the Napoleonic wars and found out about the Enlightenment and came home wanting to reform Russia. They started a secret society, wrote a constitution based on the U.S. Constitution and, on December 14, at the crucial moment of their coup attempt, lost their nerve. They had assembled troops loyal to them on Senate Square, but after a daylong standoff Czar Nicholas I dispersed these forces with cannon fire. Some of the troops ran across the Neva trying to escape; the cannons shot at the ice and shattered it and drowned them. The authorities arrested 100-some Decembrists and tried and convicted almost all. The czar sent most to Siberia; he ordered five of the leaders hanged. For us, the Decembrists’ example can be painful to contemplate

—as if King George III had hanged George Washington and sent the other signers of the Declaration of Independence to hard labor in Australia.

One good decision the Decembrists made was to not include Alexander Pushkin in their plot, although he was friends with more than a few of them. This spared him to survive and to become Russia’s greatest poet.

Tolstoy, of a younger generation than theirs, admired the Decembrists and wanted to write a book about their uprising. But the essential documents, such as the depositions they gave after their arrests, were hidden away under czarist censorship, so instead he wrote War and Peace. In Tolstoy’s lifetime the country’s revolutionary spirit veered into terrorism. Russia invented terrorism, that feature of modern life, in the 1870s. Young middle-class lawyers and university teachers and students joined terror groups of which the best known was Naródnaya Volia, or People’s Will. They went around shooting and blowing up czarist officials, and killed thousands. Alexander II, son of Nicholas I, succeeded his father in 1855, and in 1861 he emancipated the serfs. People’s Will blew him up anyway.

When Tolstoy met in 1886 with George Kennan, the American explorer of Siberia (and a cousin twice removed of the diplomat of the same name, who, more than a half-century later, devised Truman’s Cold War policy of “containment” of the Soviet Union), Kennan pleaded for support for some of the Siberian exiles he had met. But the great man refused even to listen. He said these revolutionaries had chosen violence and must live with the consequences.

Meanwhile Marxism was colonizing the brains of Russian intellectuals like an invasive plant. The intelligentsia (a word of Russian origin) sat at tables in Moscow and St. Petersburg and other cities in the empire or abroad arguing Marxist doctrine and drinking endless cups of tea, night after night, decade after decade. (If vodka has damaged the sanity of Russia, tea has been possibly worse.) Points of theory nearly impossible to follow today caused Socialist parties of different types to incubate and proliferate and split apart. The essential writer of that later-19th-century moment was Chekhov. The wistful, searching characters in his plays always make me afraid for them. I keep wondering why they can’t do anything about what’s coming, as if I’m at a scary movie and the teenage couple making out in the car don’t see the guy with the hockey mask and chain saw who is sneaking up on them.

The guy in the hockey mask was Vladimir I. Lenin. In 1887, his older brother, Aleksandr Ulyanov, a sweet young man by all accounts, joined a plot to assassinate Czar Alexander III. Betrayed by an informer (a common fate), Ulyanov was tried and found guilty, and he died on the gallows, unrepentant.

Lenin, 17 at the time, hated his family’s liberal friends who dropped the Ulyanovs as a consequence. From then on, the czar and the bourgeoisie were on borrowed time.

The Romanov dynasty stood for more than 300 years. Nicholas II, the last czar, a Romanov out of his depth, looked handsome in his white naval officer’s uniform. He believed in God, disliked Jews, loved his wife and five children, and worried especially about his youngest child, the hemophiliac only son, Alexei. If you want a sense of the last Romanovs, check out the Fabergé eggs they often gave as presents to each other. One afternoon I happened on a sponsored show of Fabergé eggs in a St. Petersburg museum. Such a minute concentration of intense, bejeweled splendor you’ve never seen. The diamond-encrusted tchotchkes often opened to reveal even littler gem-studded gifts inside. The eggs can stand for the czar’s unhelpful myopia during the perilous days of 1917. Viewers of the exhibit moved from display case to display case in reverent awe.

One can pass over some of the disasters of Nicholas’ reign. He was born unlucky on the name day of Job, the sufferer. On the day of his coronation, in 1896, a crowd of half a million, expecting a special giveaway in Moscow, panicked, trampling to death and suffocating 1,400 people. Nicholas often acted when he should have done nothing and did nothing when he should have acted. He seemed mild and benign, but after his troops killed hundreds of workers marching on the Winter Palace with a petition for an eight-hour workday and other reforms—the massacre was on January 9, 1905, later known as Bloody Sunday—fewer of his subjects thought of him as “the good czar.”

The 1905 protests intensified until they became the 1905 Revolution. The czar’s soldiers killed perhaps 14,000 more before it was under control. As a result, Nicholas allowed the convening of a representative assembly called the State Duma, Russia’s first Parliament, along with wider freedom of the press and other liberalizations. But the Duma had almost no power and Nicholas kept trying to erode the little it had. He did not enjoy being czar but believed in the autocracy with all his soul and wanted to bequeath it undiminished to his son.

It’s July 1914, just before the beginning of the First World War: The czar stands on a balcony of the Winter Palace, reviewing his army. The whole vast expanse of Palace Square is packed with people. He swears on the Bible and the holy icons that he will not sign for peace so long as one enemy soldier is standing on Russian soil. Love of the fatherland has its effect. The entire crowd, tens of thousands strong, falls to its knees to receive his blessing. The armies march. Russia’s attacks on the Eastern Front help to save Paris in 1914. Like the other warring powers, Russia goes into the trenches. But each spring, in 1915 and 1916, the army renews its advance. By 1917 it has lost more than three million men.

In America we may think of disillusionment with that war as a quasi-literary phenomenon, something felt by the writers of the Lost Generation in Paris. Long before America entered the war, Russian soldiers felt worse—disgusted with the weak czar and the German-born czarina, filled with anger at their officers, and enraged at the corruption that kept them poorly supplied. In the winter of 1916-17, they begin to appear in Petrograd as deserters and in deputations for peace, hoping to make their case before the Duma. The czar and the upper strata of Russian society insist that the country stay in the war, for the sake of national honor, and for their allies, some of whom have lent Russia money. Russia also hopes to receive as a war prize the Straits of Bosporus and the Dardanelles, which it has long desired. But the soldiers and common people see the idiocy of the endless, static struggle, and the unfair share they bear in it, and they want peace.

The absence of enough men to bring in the harvests, plus a shortage of railroad cars, plus an unusually cold winter, lead to a lack of bread in Petrograd. In February many city residents are starving. Women take to the streets and march on stores and bakeries crying the one word: “Khleb!” Bread! Striking workers from Petrograd’s huge factories, like the Putilov Works, which employs 40,000 men, join the disturbances. The czar’s government does not know what to do. Day after day in February the marches go on. Finally the czar orders the military to suppress the demonstrations. People are killed. But now, unlike in 1905, the soldiers have little to lose. They do not want to shoot; many of the marchers are young peasants like themselves, who have recently come to the city to work in the factories. And nothing awaits the soldiers except being sent to the front.

So, one after another, Petrograd regiments mutiny and join the throngs on the streets.

Suddenly the czar’s government can find no loyal troops willing to move against the demonstrators. Taking stock, Nicholas’ ministers and generals inform him that he has no choice but to abdicate for the good of the country. On March 2 he complies, with brief complications involving his son and brother, neither of whom succeeds him.

Near-chaos ensues. In the vacuum, power is split between two new institutions: the Provisional Government, a cabinet of Duma ministers who attempt to manage the country’s affairs while waiting for the first meeting of the Constituent Assembly, a nationwide representative body scheduled to convene in the fall; and the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, a somewhat amorphous collection of groups with fluid memberships and multi-Socialist-party affiliations. (In Russian, one meaning of the word “soviet” is “council”—here, an essentially political entity.) The Petrograd Soviet is the working people’s organization, while the Provisional Government mostly represents the upper bourgeoisie. This attempt at dual governance is a fiction, because the Petrograd Soviet has the support of the factory workers, ordinary people and soldiers. In other words, it has the actual power; it has the guns.

The February Revolution, as it’s called, is the real and original Russian revolution. February supplied the raw energy for the rest of 1917—energy that Lenin and the Bolsheviks would co-opt as justification for their coup in October. Many classic images of the people’s struggle in Russia derive from February. In that month red became the color of revolution: Sympathetic onlookers wore red lapel ribbons, and marchers tore the white and blue stripes from the Russian flag and used the red stripe for their long, narrow banner. Even jaded Petrograd artistic types wept when they heard the self-led multitudes break into “The Marseillaise,” France’s revolutionary anthem, recast with fierce Russian lyrics. Comparatively little blood was shed in the February Revolution, and its immediate achievement—bringing down the Romanov dynasty—made a permanent difference.

Unlike the coup of October, the February uprising had a spontaneous, popular, tectonic quality. Of the many uprisings and coups and revolutions Russia has experienced, only the events of February 1917 seemed to partake of joy.

2

The city of St. Petersburg endlessly explains itself, in plaques and monuments everywhere you turn. It still possesses the majesty of an imperial capital, with its plazas, rows of 18th- and 19th-century government buildings receding to a vanishing point, glassy canals and towering cloudscapes just arrived from the Baltic Sea. The layout makes a grand backdrop, and the revolution was the climactic event it served as a backdrop for.

A taxi dropped me beside the Fontanka Canal at Nevskii Prospekt, where my friend Luda has an apartment in a building on the corner. Luda and I met 18 years ago, when Russian friends who had known her in school introduced us. I rented one of several apartments she owns in the city for a few months in 2000 and 2001. We became friends despite lack of a common language; with my primitive but slowly improving Russian and her kind tolerance of it, we made do. Now I often stay with her when I’m in the city.

When we first knew each other Luda worked for the local government and was paid so little that, she said, she would be able to visit the States only if she went a year without eating or drinking. Then she met a rich Russian-American, married him and moved to his house in Livingston, New Jersey, about ten miles from us. After her husband died she stayed in the house by herself. I saw her often, and she came to visit us for dinner. The house eventually went to her husband’s children, and now she divides her time between St. Petersburg and Miami. I have more phone numbers for her than for anyone else in my address book.

Her Nevskii apartment’s mid-city location is good for my purposes because when I’m in St. Petersburg I walk all over, sometimes 15 miles or more in a day. One morning, I set out for the Finland Station, on the north side of the Neva, across the Liteynyi Bridge from the city’s central district. The stroll takes about 20 minutes. As you approach the station, you see, on the square in front, a large statue of Lenin, speaking from atop a stylized armored car. One hand holds the lapel of his greatcoat, the other arm extends full length, gesturing rhetorically. This is your basic and seminal Lenin statue. The Finlandskii Voksal enters the story in April of 1917. It’s where the world-shaking, cataclysmic part of the Russian Revolution begins.

Most of the hard-core professional revolutionaries did not participate in the February Revolution, having been earlier locked up, exiled or chased abroad by the czar’s police. (That may be why the vain and flighty Alexander Kerensky rose to power so easily after February: The major-leaguers had not yet taken the field.)

Lenin was living in Zurich, where he and his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, had rented a small, disagreeable room. Awaiting developments, Lenin kept company with other expatriate Socialists, directed the Petrograd Bolsheviks by mail and telegram, and spent time in the public library. He did not hear of the czar’s abdication until some time after the fact. A Polish Socialist stopped by and brought news of revolution in Russia in the middle of the day, just after Krupskaya had finished washing the lunch dishes. Immediately Lenin grew almost frantic with desire to get back to Petrograd. His wife laughed at his schemes of crossing the intervening borders disguised as a speech- and hearing-impaired Swede, or of somehow obtaining an airplane.

Leon Trotsky, who would become the other major Bolshevik of the revolution, was then living in (of all places) the Bronx. With his wife and two young sons he had recently moved into a building that offered an elevator, garbage chute, telephone and other up-to-date conveniences the family enjoyed. Trotsky hailed the February Revolution as a historic development and began to make arrangements for a trans-Atlantic voyage.

Both Trotsky and Lenin had won fame by 1917. Lenin’s Bolshevik Party, which emerged from the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party in 1903, after splitting with the more moderate Mensheviks, kept its membership to a small group of dedicated followers. Lenin believed that the Bolsheviks must compromise with nobody. Since 1900, he had lived all over Europe, spending more time outside Russia than in it, and emphasized the international aspect of the proletariat revolution. Lenin wrote articles for Socialist journals and he published books; many devotees knew of him from his writings. Trotsky also wrote, but he was a flashier type and kept a higher public profile. Born Lev Davidovich Bronstein in the Ukraine, he had starred in the 1905 Revolution: At only 26 he organized a Soviet of Workers’ Deputies that lasted for 50 days before the government crushed it.

Lenin’s return to Russia required weeks of arrangements. Through German contacts he and a party of other exiled revolutionaries received permission to go by train via Germany, whose government encouraged the idea in the hope that Lenin and his colleagues would make a mess of Russia and thereby help Germany win the war. In pursuit of their political ends Lenin and the Bolsheviks acted as German agents and their policy of “revolutionary defeatism” strengthened the enemy. They went on to receive tens of millions of German marks in aid before the Kaiser’s government collapsed with the German defeat, although that collusion would not be confirmed until later.

The last leg of Lenin’s homeward journey led through Finland.

Finally, at just after 11 on the night of April 16, he arrived in Petrograd at the Finland Station. In all the iconography of Soviet Communism few events glow as brightly as this transfiguring arrival. Lenin and his fellows assumed they would be arrested upon stepping off the train. Instead, they were met by a band playing “The Marseillaise,” sailors standing in ranks at attention, floral garlands, a crowd of thousands and a searchlight sweeping its beam through the night. The president of the Petrograd Soviet, a Menshevik, welcomed Lenin with a condescending speech and reminded him that all Socialists now had to work together. Lenin listened abstractedly, looking around and toying with a bouquet of red roses someone had given him. When he responded, his words “cracked like a whip in the face of the ‘revolutionary democracy,’” according to one observer.

Turning to the crowd, Lenin said,

Dear Comrades, soldiers, sailors, and workers!

I am happy to greet in your persons the victorious Russian revolution, and to greet you as the vanguard of the worldwide proletarian army…the hour is not far distant when at the call of our comrade Karl Liebknecht, the people of Germany will turn their arms against their own capitalist exploiters…The worldwide Socialist revolution has already dawned…the Russian revolution accomplished by you has prepared the way and opened a new epoch. Long live the worldwide Socialist revolution!

A member of the Petrograd Soviet named Nikolai Sukhanov, who later wrote a seven-volume memoir of the revolution, heard Lenin’s speech and was staggered. Sukhanov compared it to a bright beacon that obliterated everything he and the other Petrograd Socialists had been doing. “It was very interesting!” he wrote, though he hardly agreed with it. I believe it affected him—and all of Russia, and the revolution, and a hundred years of subsequent history—because not since Peter the Great had anyone opened dark, remote, closed-in Russia so forcefully to the rest of the world. The country had long thought of itself as set apart, the “Third Rome,” where the Orthodox Faith retained its original and unsullied purity (the Second Rome having been Constantinople). But Russia had never spread that faith widely abroad.

Now Lenin informed his listeners that they had pioneered the international Socialist revolution, and would go forth into the world and proselytize the masses. It was an amazing vision, Marxist and deeply Russian simultaneously, and it helped sustain the despotic Bolsheviks, just as building St. Petersburg, no matter how brutal the cost, drove Peter the Great 200 years before. After Lenin, Russia would involve itself aggressively in the affairs of countries all over the world. That sense of global mission, soon corrupted to strategic meddling and plain troublemaking, is why America still worries about Russia today.

Making his ascension to the pantheon complete, Lenin then went out in front of the station and gave a speech from atop an armored car. It is this moment that the statue in the plaza refers to. Presumably, the searchlight illuminated him, film-noirishly.

As the armored car slowly drove him to Bolshevik headquarters he made more speeches standing on the vehicle’s hood. Items associated with this holy night have been preserved as relics.

The steam engine that pulled the train that Lenin arrived in resides in a glass enclosure next to the Finland Station’s Platform Number 9. And an armored car said to be the same one that he rode in and made the speeches from can be found in an unfrequented wing of the immense Artillery Museum, not far away.

Guards are seldom in evidence in the part of the museum where the historic bronevik sits permanently parked. Up close the armored car resembles a cartoon of a scary machine. It has two turrets, lots of rivets and hinges, flanges for the machine guns, solid rubber tires, and a long, porcine hood, completely flat and perfect for standing on. The vehicle is olive drab, made of sheet iron or steel, and it weighs about six tons. With no guard to stop me I rubbed its cold metal flanks. On its side, large, hand- painted red letters read: VRAG KAPITALA, or “Enemy of Capital.”

When Lenin mounted this metal beast, the symbolic connection to Peter the Great pulled tight. Falconet’s equestrian Peter that rears its front hooves over Senate Square—as it reared over the dead and wounded troops of the Decembrists in 1825—haunts the city forever. It’s the dread “Bronze Horseman” of the Pushkin poem. Gesturing dramatically from atop his armored beast-car, Lenin can be construed as re-enacting that statue, making it modernist, and configuring in his own image the recently deposed Russian autocracy.

Alone with the beast in the all-but-deserted Artillery Museum, I went over it again. At its back, on the lower corners on each side, two corkscrew-shaped iron appendages stuck out. I could not imagine what they were for. Maybe for attaching to something? But then why not use a simple metal hitch or loop? I still don’t know. And of course the appendages looked exactly like the tails of pigs. Russia is an animist country. In Russia all kinds of objects have spirits. Non-animal things are seen as animals, and often the works of men and women are seen as being identical with the men and women themselves. This native animism will take on special importance in the case of Lenin.

Bolshevik headquarters occupied one of the city’s fanciest mansions, which the revolutionaries had expropriated from its owner, a ballerina named Matilda Kshesinskaya. Malice aforethought may be assumed, because Kshesinskaya had a thing for Romanovs. After a performance when she was 17, she met Nicholas, the future czar, and they soon began an affair that lasted for a few years, until Alexander III died. Nicholas then ascended the throne and married the German princess Alix of Hesse (thenceforth to be known as Empress Alexandra Feodorovna). After Nicholas, the ballerina moved on to his father’s first cousin, Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich. During her affair with that grand duke, she met another one—Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich, Nicholas’ first cousin. They also began an affair. Such connections helped her to get good roles in the Imperial Ballet, although, in fairness, critics also regarded her as an outstanding dancer.

Whom she knew came in handy during the hard days of the war. In the previous winter the British ambassador, Sir George Buchanan, had been unable to find coal to heat his embassy. He even asked the head of the Russian Navy, who said there was none. While out on a walk with the French ambassador,

Buchanan happened to see four military lorries at Kshesinskaya’s house and a squad of soldiers unloading sacks of coal. “Well, if that isn’t a bit too thick!” Buchanan remarked. Good contacts kept her a step ahead of events in 1917. Warned, Kshesinskaya fled with her more portable valuables before the Bolsheviks arrived. Later she and her son and Grand Duke Andrei emigrated to Paris, where she ran a ballet school and lived to be almost 100 years old. A movie, Matilda, based on her affair with Nicholas, is due to be released in Russia on October 25, 2017. Admirers of Nicholas have sought to ban it, arguing that it violates his privacy.

The mansion, an example of the school known as Style Moderne, won a prize for the best building facade in St. Petersburg from the City Duma in 1910, the year after its construction. It sits on a corner near Trinity Square, and from a second-story French window a balcony with decorative wrought-iron grillwork extends above the street. In Soviet times the mansion became the Museum of the October Revolution, said to be confusing for its many omissions, such as not showing any pictures of Trotsky.

Today the building houses the Museum of Russian Political History, which tells the story of the revolution in clear and splendid detail, using text, photos, film, sounds and objects.

I have spent hours going through its displays, but my favorite part of the museum is the balcony. I stand and stare at it from the sidewalk. Upon his arrival from the Finland Station, Lenin made a speech from this balcony. By then he had grown hoarse. Sukhanov, who had followed the armored car’s procession, could not tear himself away. The crowd did not necessarily like what it heard, and a soldier near Sukhanov, interpreting Lenin’s internationalist sentiments as pro-German, said that he should be bayoneted—a reminder that although “Bolshevik” meant, roughly, “one of the majority,” not many ordinary Russians, or a majority of Socialists, or even all Bolsheviks, shared Lenin’s extreme views.

Lenin gave other speeches from the balcony during the three months more that the Bolsheviks used the mansion. Photographs show him speaking from it, and it appears in Socialist Realist paintings. A plaque notes the balcony’s revolutionary role, but both plaque and subject are above eye level, and no passersby stop to look. In fact, aside from the pope’s balcony in Rome, this may be the most consequential balcony in history. Today the ground where the listeners stood holds trolley-bus tracks, and cables supporting the overhead electric wires attach to bolts in the wall next to the balcony.

I can picture Lenin: hoarse, gesticulating, smashing the universe with his incisive, unstoppable words; below him, the sea of upturned faces. Today an audience would not have much room to gather here, with the trolley buses, and the fence enclosing a park just across the street. Like a formerly famous celebrity, this small piece of architecture has receded into daily life, and speeches made from balconies no longer rattle history’s windowpanes.

In the enormous three-ring shouting match and smoke-filled debating society that constituted revolutionary Petrograd during the months after the czar’s removal, nobody picked the

Bolsheviks to win. You had parties of every political ilk, from far left to far right, and schismatic groups within them, such as the Social-Democratic Labor Party’s less radical wing (the Mensheviks); another powerful party, the Socialist- Revolutionaries, had split contentiously into Left SR’s and Right SR’s. Added to these were many other parties, groups and factions—conservatives, populists, moderates, peasant delegations, workers’ committees, soldiers’ committees, Freemasons, radicalized sailors, Cossacks, constitutional monarchists, wavering Duma members. Who knew what would come out of all that?

Under Lenin’s direction the Bolsheviks advanced through the confusion by stealth, lies, coercion, subterfuge and finally violence. All they had was hard-fixed conviction and a leader who had never been elected or appointed to any public office. Officially, Lenin was just the chairman of the “Central Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party (Bolsheviks),” as their banner read.

The dominant figure of Alexander Kerensky, a popular young lawyer, bestrode these days like a man with one foot on a dock and the other on a leaky skiff. He came from the city of Simbirsk, where his family knew the Ulyanovs. His father had taught Lenin in high school. Kerensky had defended revolutionaries in court and sometimes moved crowds to frenzy with his speeches. As the vice chairman of the Petrograd Soviet and, simultaneously, the minister of war (among other offices) in the Provisional Government, he held unique importance. Dual government, that practical implausibility, embodied itself in him.

Some participants in the Russian Revolution could not get the fate of the French Revolution out of their heads, and Kerensky was among them. When spring moved toward summer, he ordered a new, make-or-break offensive in the war, and soon mass demonstrations for peace boiled over again in Petrograd. The Bolsheviks, seeing advantage, tried to seize power by force in April and again in early July, but Kerensky had enough troops to shut these tentative coup attempts down. Also, Lenin’s traitorous connection to the Germans had begun to receive public attention. Concerned about being arrested or lynched, he hurried back to Finland. But Kerensky felt only contempt for the Bolsheviks. Thinking of Napoleon’s rise, he mainly dreaded a counterrevolution from the right.

This predisposition caused him to panic in August while trying to keep the war going and supply himself with loyal troops in the capital. After giving ill-considered and contradictory orders that caused one general, fearing arrest, to shoot himself, Kerensky then accused the commanding general, Lavr Kornilov, of mutiny. Kornilov, who had not, in fact, mutinied, became enraged by the charge and decided to mutiny for real. He marched on Petrograd, where a new military force, the Red Guards, awaited him. This ad-hoc people’s militia of young workers and former Russian Army soldiers carried weapons liberated in the February mutinies. Rallied by the Bolsheviks, the Red Guards stopped Kornilov before he reached the capital. The Kornilov episode strengthened the Bolsheviks’ credibility and destroyed Kerensky’s support among the regular military. Now he would not have an army when he needed one.

With Lenin in hiding, Trotsky kept the Bolsheviks on message with their promise of “Bread, Peace, and Land.” The first two watchwords were self-explanatory, and the third went back to a hope the peasants had nourished since before emancipation in the 19th century. Their wish that all privately held lands would be distributed to the smaller farmers ran deep. The slogan’s simplicity had an appeal; none of the promises would be fulfilled, but at least the party knew what people wanted to hear. In September, for the first time, the Bolsheviks won a majority of seats in the Petrograd Soviet. Responding to perceived threats from “Kornilovites” and other enemies of the revolution, the Petrograd Soviet also established its Military Revolutionary Committee, or MRC. For the Bolsheviks, this put an armed body of men officially at their command.

Lenin sneaked back from Finland but remained out of sight. Kerensky now held the titles of both prime minister and commander in chief, but had lost most of his power. The country drifted, waiting for the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets that was set to meet in October, and beyond that, for the promised first gathering of the Constituent Assembly. Both these bodies would consider the question of how Russia was to be governed. Lenin knew that no better time for a takeover would ever present itself. He wanted to act quickly so as to hand the upcoming assemblies a fait accompli. Through the night of October 10, in the apartment of a supporter, Lenin argued with the other 11 members of the party’s Central Committee who were there. Relentlessly, he urged an immediate armed takeover. Several of the dissenters thought he was moving too fast.

By morning the committee voted in his favor, 10 to 2.

3

One can read about these events in Sukhanov’s The Russian Revolution 1917: A Personal Record (a good abridgment came out in 1984); or in Richard Pipes’ classic, The Russian Revolution; or in Edmund Wilson’s fascinating intellectual history, To the Finland Station; or in Trotsky’s extensive writings on the subject; or in many other books. For the coup itself I rely on my hero, John Reed.

I first became swept up in the story of the Russian Revolution when I read Reed’s landmark eyewitness account, Ten Days That Shook the World. Reed went to Harvard, class of 1910, and joined the humor magazine, the Lampoon. He had the college- boy hair of that era, the kind that went up and back, in waves— Mickey Rooney hair. None of the fancier clubs asked him to join, and I wouldn’t wonder if the pain of that, for a young man whose family had some standing in far-off Portland, Oregon, didn’t help make him a revolutionary. When I joined the Lampoon, 59 years later, a member pointed out to me the building’s stained-glass window in memory of Reed. It shows a silver hammer and sickle above Reed’s name and year, on a Communist-red background. Supposedly the window had been a gift from the Soviet Union. The strangeness of it gave me shivers. At that stage of the Cold War, Russian missiles were shooting down American jets in Vietnam. How had this man come to be revered by the other side?

Reed dwelt in romance. Everything he did had style. In college he cut a wide swath, leading the cheers at football games, writing plays, publishing poetry and tossing off grand gestures, like hopping a ship for Bermuda during spring break and returning to campus late and getting in trouble with the dean. Three years after graduation he was riding with Poncho Villa’s rebels in Mexico. Insurgent Mexico, the book he wrote about the experience, made him famous at 27. When the First World War started he decamped to Europe. On a tour of the front lines he somehow managed to cross over to the entrenchments of the Germans, where, at the invitation of a German officer, he fired a couple of shots in the direction of the French. When he returned to New York, news of this exploit got out, and afterward the French quite understandably refused to let him back into France.

So he made his next trip to the Eastern Front instead. The journey brought him to Russia, and to a passion for the country that would determine the rest of his life. In his 1916 book The War in Eastern Europe, Reed wrote:

[Russia is] an original civilization that spreads by its own power…And it takes hold of the minds of men because it is the most comfortable, the most liberal way of life. Russian ideas are the most exhilarating, Russian thought the freest, Russian art the most exuberant; Russian food and drink are to me the best, and Russians themselves are, perhaps, the most interesting human beings that exist.

Yikes! As an intermittent sufferer of this happy delusion myself, I only note that it may lead a person astray. In 1917, paying close attention to events, Reed knew he had to return to Russia. He arrived in Petrograd in September, not long after the Kornilov mutiny. (With him was his wife, the writer Louise Bryant.) What he saw around him thrilled him. He had participated in strikes and protests in the U.S., gone to jail, and shared in the hope of an international socialist revolution. “In the struggle my sympathies were not neutral,” he wrote in the preface to Ten Days. With the unsleeping strength of youth he went everywhere in Petrograd and saw all he could. By limiting a vast historical movement to what he experienced over just a short period (in fact, a span somewhat longer than ten days), he allowed his focus to get up-close and granular.

St. Petersburg has not changed much from when it was revolutionary Petrograd. The Bolsheviks’ move of the government to Moscow in 1918 exempted the former capital from a lot of tearing-down and rebuilding; becoming a backwater had its advantages. In places where Reed stood you can still picture how it looked to him. He wrote:

What a marvelous sight to see Putilovsky Zavod [the Putilov Factory] pour out its forty thousand to listen to Social Democrats, Socialist Revolutionaries, anarchists, anybody, whatever they had to say, as long as they would talk!

Today that factory is called Kirovsky Zavod and it has its own metro station of that name, on the red line, southeast of the city center. Photographs from 1917 show the factory with a high wall along it and big crowds of people on the street in front. Now the

wall and the factory’s main gate are almost the same as then. Next to the gate a big display highlights some of what is built here—earthmovers, military vehicles, atomic reactor parts. The factory wall, perhaps 15 feet high, runs for half a mile or more next to the avenue that adjoins it. Traffic speeds close by; no large crowds of workers could listen to speakers here. Like many of the public spaces important in the revolution this one now belongs to vehicles.

At a key moment in the Bolsheviks’ takeover, Reed watched the army’s armored-car drivers vote on whether to support them. The meeting took place in the Mikhailovsky Riding School, also called the Manège, a huge indoor space where “some two thousand dun-colored soldiers” listened as speakers took turns arguing from atop an armored car and the soldiers’ sympathies swung back and forth. Reed observes the listeners:

Never have I seen men trying so hard to understand, to decide. They never moved, stood staring with a sort of terrible intentness at the speaker, their brows wrinkled with the effort of thought, sweat standing out on their foreheads; great giants of men with the innocent clear eyes of children and the faces of epic warriors.