Issue of the Week: War, Human Rights, Disease, Hunger, Economic Opportunity, Population, Environment, Personal Growth

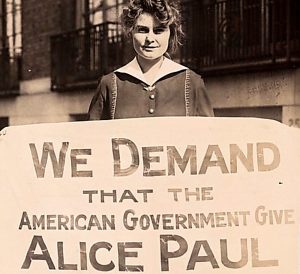

Lucy Branham protests Alice Paul imprisonment, The Great War, PBS 2018

Yesterday was the Veteran’s Day holiday in the US. The actual date of Veteran’s Day was the day before, Sunday, November 11. This was also Armistice Day and Remembrance Day in various nations worldwide.

It’s origins were the armistice day ending World War One.

Sunday, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the exact moment of the 100th anniversary of the end of World War One, known as The Great War, occurred.

The three-part six hour series, The Great War, from the American Experience franchise, premiered on PBS last year and was aired again on the eve of the 4th of July this year.

American Experience is another of the superb documentary series brought to us by PBS affiliate WGBH in Boston–the same outfit that has brought us Frontline.

It is impossible to overstate the significance of World War One on virtually every issue facing humanity. The war itself was by far the bloodiest in human history until it’s successor only two decades later, World War Two. The former formed the increasingly connected world we are in today as much as the latter.

The First World War is the most important event most people don’t know about. It’s a Pandora’s box. And we’re still ironing out everything that that war unleashed.

That’s one of the opening lines from The Great War.

The series is from an American perspective to be sure and is intended to be. The importance of this is obvious. America emerged from the war as the pre-eminent global power in many ways, cementing that role in World War Two.

We can’t cover everything here, so we cover this. However, we cannot overemphasize the importance of your own exploration of every aspect of this global conflict, its relationship to issues of equality and class, colonialism, sexism, racism, events since and to this moment all over the world–and to the usual underpinnings of basic needs and rights, deprived and achieved in the ongoing process we continuously focus on.

In the US, many of these issues are covered in The Great War. There are a number of excellent related articles and videos on the site the series can be streamed from.

We specifically bring to focus here the movement to bring women the vote, A Woman’s War, as a related article below describes it. As we’ve said before, it took until this moment, in the US and a number of other places, for half of the species to gain this basic right.

Just as we have noted before, it was the women who brought revolution to Russia and gained their right to vote in the doing. It was also a revolution made possible in many ways by World War One, and the calamity of the eastern front for Russia. It was also a revolution whose betrayal was made possible in many ways by the same thing. We’ve covered that at great length before.

The revolution by women in the US that led to their right to vote owes its success in the main to the singular will of Alice Paul and those who supported her strategy. (Paul and her close friend and ally, Lucy Burns, had learned at the side of Emmeline Pankhurst in the UK, where the first part of the women’s vote was gained in 1918.) Women were the first to protest at The White House, during wartime, decrying the hypocrisy of a war claiming to be for democracy that denied democracy to them, getting them imprisoned with their lives on the line, with Alice Paul on hunger-strike–until they won.

Last Tuesday, women led the way to Democrats retaking control of the House of Representatives in the US, with more than 100 women (votes are still being tabulated for the final count) in the new House–the most in US history.

Some of these women served in the US armed forces–an armed forces that finally, under President Obama, officially recognized the right of women to undergo the same training alongside men and fight equally in combat. Many have qualified, with many of their male comrades seeing them as equals and more (some have said some of the women have been so impressive that they would chose them first to fight alongside)–further putting the lie to the weaker sex mendacity forming part of the rotten core of sexism.

More than one hundred women elected to the US House, as reported by CBS on the Veteran’s Day Holiday in the US–exactly one hundred years after President Woodrow Wilson was forced by both parties and public opinion to cave in to Alice Paul and the radical suffragists of the National Women’s Party (NWP), reversing course and announcing support for a constitutional amendment giving women the vote, as a war measure in the waning days of the war. The more mainstream National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) that Paul had left to form NWP also had an impact, but the momentum on the issue had been stuck at only a few states adopting the vote for women until the activism of the NWP indisputably changed the dynamics. The first vote in 1918 passed with the needed two-thirds in the House by a vote, but failed by two votes in the Senate. It passed in 1919 and was ratified in 1920.

Related articles and links are posted after the transcripts of The Great War below

We provide the transcripts of this epic series and highly recommend reading them. It’s more than a long-read–it is the equivalent of reading a short book.

But this is a case where we emphatically say that viewing the series is the more necessary thing to do. The writing is meant to accompany the images. And they are images never seen or put together in such an extraordinary way before.

Here is The Great War.

Part 1

Narrator: In the summer of 1917, at docks up and down the eastern seaboard, thousands of American soldiers boarded ships bound for France. They were the vanguard of a new American army, about to enter the most destructive war the world had ever known.

Richard Slotkin, Historian: It’s a watershed in American history. The United States goes from being the country on the other side of the ocean to being the preeminent world power.

Narrator: For President Woodrow Wilson, the war was a crusade “to make the world safe for democracy,” a chance to transform the international order in America’s image.

David M. Kennedy, Historian: Woodrow Wilson himself said, “it was of this that we dreamed at our birth, for which we were destined.” leading the way for the world to a new order of peace.

Jennifer D. Keene, Historian: This is the birth of the on-going debate over how involved America should be in the world.

Narrator: The troops were drawn from every corner of the country, and reflected the teeming diversity of turn-of-the-century America.

Helen Zoe Veit, Historian: In many ways World War I forced Americans to ask what are we as a country? Who are we as a people?

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: I think it’s a war that Americans fought together which required them to meet one another, to confront one another and figure out what was holding their society together.

Narrator: All across the country, communities staged elaborate celebrations to send their men off to war. But underneath the calls for unity, Americans were deeply divided.

Adriane Lentz-Smith, Historian: World War I showed Americans the best and worst that the country is capable of. It lays bare questions the Americans continue to ask themselves for the rest of the 20th century.

A. Scott Berg, Writer: This was a period of deep paranoia in this country. It’s probably the greatest suppression of free speech the country has ever seen.

Narrator: Women who refused to set aside their campaign for suffrage because of the war were set upon by mobs and carted off to prison. African-American men joined in a war for freedom abroad, while being denied it at home.

Chad Williams, Historian: The war galvanizes African Americans, not just to fight for their country, but to fight for their rights as American citizens.

Narrator: When the ships let loose their lines and headed out to sea, the troops on board were entering a conflict of unprecedented bloodshed and suffering, one that had come to be known as The Great War.

Dan Carlin, Podcast Producer: The First World War is the most important event most people don’t know about. It’s a Pandora’s box. And we’re still ironing out everything that that war unleashed.

Outbreak

Narrator: In the summer of 1914, a new prospect named Babe Ruth began playing for the Boston Red Sox. Crowds were flocking to theaters to see the newest film by Charlie Chaplin. A loaf of bread cost six cents. Henry Ford’s Model T sold for $500 dollars. In 1914, the nation boasted a population of almost a hundred million people. A third of them were immigrants, or had parents who had been born abroad. And one out of three Americans lived on farms. Women could vote, but only in twelve states of the union. In the South, African Americans had virtually no political rights at all. In 1914, the United States Army ranked seventeenth in the world, behind Serbia’s. Europe was a one-week steamship voyage away. The British pound was the world’s reserve currency.

David M. Kennedy, Historian: In 1914 the United States was the largest producer of steel. It had the biggest transportation network. It had more energy resources. It had the second biggest population in the western world saving only Russia. But the American people as a whole were quite ambivalent about whether or not they actually wanted to become one of the great powers that arbitrated the destinies of the world at large.

Narrator: To mark the Fourth of July in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson delivered a speech from the steps of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. After paying tribute to what he called the “energy and variety and wealth” of America, he posed a question: “What are we going to do with the influence and power of this great Nation?”

Adriane Lentz-Smith, Historian: I think that Wilson had, even in 1914 this vision of America as a moral beacon in the world, as a city upon a hill, this sense that Americans had something to give to the world.

Narrator: Europe, meanwhile, was a bastion of culture and enlightenment, but beset by ancient dynasties and autocratic rulers competing to control the world’s resources. Germany was led by a kaiser, Russia a tsar. An emperor lay claim to Austria Hungary while a sultan reigned over the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Great Britain and France, two democracies, jealously guarded far-flung colonial empires. Only a month after Wilson’s speech, Americans struggled to make sense of news coming from the other side of the Atlantic. The assassination of an obscure Austro-Hungarian aristocrat by a Serbian nationalist had provided a pretext to unleash imperial rivalries that were breaking the continent apart. Germany and its ally, Austria Hungary, declared war on Serbia and her ally, Russia. Germany then invaded France — through neutral Belgium — and Russia. Britain came to the aid of, the French and the Belgians and suddenly, millions of men were fighting a war whose very purpose seemed hard to comprehend.

Margaret MacMillan, Historian: What were they thinking? They had so much going for them. Europe was the most prosperous part of the world, the most powerful part of the world. It had had extraordinary progress. It had a century of almost unbroken peace, and suddenly they blundered into this war. And I think the reaction in the United States was “what on earth are they doing?” And thank goodness we’re 3,000 miles away.

Narrator: “The general conflagration has begun,” Wilson’s ambassador to England, Walter Page, observed. “Ours is the only great government in the world that is not in some way entangled.” The Atlantic Ocean provided the United States with protection against the European contagion. But Wilson also saw in America’s unique position a chance to influence the course of world events. On August 4th, he wrote to the leaders of the newly warring nations that he would “welcome an opportunity to act in the interest of European peace.”

A. Scott Berg, Writer: Almost from the outset of the war, Woodrow Wilson was trying to find diplomatic solutions. He believed if all the heads of state could sit at a table and confer, they could probably have ended this war. There didn’t have to be a war here.

Narrator: As he faced the greatest international crisis of his presidency, Woodrow Wilson was falling apart. In a small bedroom on the second floor of the White House, his wife Ellen lay dying. They had been married for 29 years, and she had borne him three daughters, standing by him during his dramatic rise to the White House. Now, she was gravely ill with Bright’s disease, a fatal inflammation of the kidneys. Two days after war broke out, at five in the afternoon, she died. “I never understood before what a broken heart meant and did for a man,” Wilson wrote to a friend. “It just means that he lives by the compulsion of necessity and duty only.”

A. Scott Berg, Writer: Here is the president of the United States who is so bereft he is actually contemplating giving up the office. He does not know how he can go on without this woman, who really sacrificed everything she could for him.

Narrator: “It is pathetic to see the President,” his son-in-law lamented “He hardly knows where to turn.” A devastated Wilson could barely manage Ellen’s funeral arrangements. He sat next to the casket during a sleepless train ride back to her family home in Georgia. For the first time in decades, Woodrow Wilson was facing the future alone. The son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister from Virginia, he was a bookish young man with a delicate constitution who became a successful lawyer and scholar of American government.

Richard Rubin, Writer: He was a former professor, a former college president and the governor of New Jersey. He had a meteoric rise in politics and in an age of oratory, he was a very fine speaker.

A. Scott Berg, Writer: Woodrow Wilson was the most religious president we ever had. Woodrow Wilson is a man who got on his knees twice a day and prayed. He read scripture every night. He said grace before every meal. His faith informed everything he ever said, everything he ever thought, everything he ever did.

Narrator: An idealistic Democratic crusader, Wilson had spent his first two years in office driving through Congress a historic set of progressive reforms. His penchant for soaring rhetoric masked a pragmatic, and often ruthless, politician. He was also the first Democrat from the South to be elected president since Reconstruction. One of Wilson’s first acts was to reintroduce segregation in federal agencies in Washington. Almost overnight, thousands of promising civil service jobs that had been a path of upward mobility for African Americans were now open to whites only.

Adriane Lentz-Smith, Historian: Wilson felt that forward thinking white people were really best positioned to see to the well being of African Americans. And I think he felt confident that at some point African Americans would be able to be incorporated into the larger civic and democratic body in some way. But they hadn’t reached the point in their evolution yet.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: He makes almost no effort to bring African Americans into any role in the government and in fact takes so many steps to alienate them that many African Americans who thought he would be a progressive on race become bitterly disappointed in him.

Narrator: His southern upbringing also profoundly shaped Wilson’s views about war and peace.

A. Scott Berg, Writer: Woodrow Wilson is the only United States president who was born in a country that had lost a war, the Confederate States of America. He remembered the…the devastation, the deprivation, the degradation that comes from losing a war. He carried that with him.

Margaret MacMillan, Historian: Woodrow Wilson doesn’t like war. He believes in democratic values, liberal values, he believes in peace. He doesn’t want to take the United States into war.

Narrator: On August 18th, Wilson emerged from his grieving long enough to issue a proclamation. “The United States must be neutral in fact, as well as in name,” he declared. “We must be impartial in thought, as well as action.” But in the same breath, the president acknowledged that the unity he was asking of his fellow citizens was a challenge given America’s diverse population. “The people of the United States are drawn from many nations, and chiefly the nations now at war,” he proclaimed “some will wish one nation, others another, to succeed in the momentous struggle.”

Richard Rubin, Writer: America is not a monolith. America is composed of a great many different communities. Take New York City. You had Irish who had no desire to go over and fight for the British king. You had Russian Jews who had no desire to go over and fight for the Tsar. You had German-American immigrants and Austrian-American immigrants who had no desire to go over and fight against their country.

Margaret MacMillan, Historian: In Woodrow Wilson’s day, the United States hadn’t become the world’s policeman. And I don’t think the United States felt an obligation to engage in the world and as far as Europe was concerned, I mean for a lot of Americans they looked across the Atlantic and said well, they’re idiots, they’re fools, they’re probably worse, let them do it. He didn’t want the United States to be involved.

Narrator: For now, Wilson believed, America must bide its time, and remain “a nation that . . . keeps herself fit and free to do what is honest and disinterested and truly serviceable for the peace of the world.” But he was also keenly aware that the right to influence the chaos unfolding in Europe might require an unprecedented projection of American power.

Adriane Lentz-Smith, Historian: Part of what’s driving him is a genuine commitment, trying to apply what he sees as American principles to the world for the betterment of the world. He thinks America has something to teach everyone. Part of it is ego. Wilson believes himself able to deliver these democratic practices to the global stage. He sees himself as well equipped to be this person.

Narrator: Ambassador Page saw little chance that America could stay detached from the great conflict that was shaking the world to its foundations. “We shall need somehow to wake up the American public to realize that our isolation is gone,” he wrote to the president, “There simply is no end to the changes that are coming.”

Atrocities

Narrator: The day war broke out, the impeccably tailored American war correspondent Richard Harding Davis settled into his first class cabin on board a ship bound for France, and enjoyed a cold glass of champagne. Davis was perhaps the most famous journalist of his day, and the war promised to be the biggest story of his already legendary career. He had made a name for himself reporting for the newspapers owned by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, filing dispatches from war zones around the world. His vivid reports of the exploits of the Rough Riders in Cuba had helped catapult the young Theodore Roosevelt to national renown. Now Americans were counting on Davis to bring them news of the shocking developments in Europe. While he was crossing the Atlantic in the first week of August, 1914, German troops continued their invasion of neutral Belgium, rushing to encircle Paris and defeat the French and the British before the huge Russian armies to the east could mobilize.

Dan Carlin, Podcast Producer: The German war plans called for them to defeat France first, within a short period of time, and then turn those armies on the Russians. The attitude was if they didn’t do it quickly enough the Russian steamroller would come tumbling into the eastern German territories on the way to Berlin.

Jay Winter, Historian: The German army was well aware that its task was to arrive in Paris 42 days…not 43 days…42 days exactly after the invasion of Belgium. And the population in Belgium and northern France was not going to stand in the way.

Narrator: By August 17th, as hundreds of thousands of Belgian refugees were streaming away from the advancing German army, Davis had commandeered a motorcar and was headed in the opposite direction. He managed to find his way to Brussels to witness German forces entering the Belgian capital.

Voice: Richard Harding Davis: The entrance of the German army into Brussels has lost all human quality. . . . No longer was it regiments of men marching but something uncanny, inhuman, a force of nature. . . This was a machine, endless, tireless, with the delicate organization of a watch and the brute power of a steam roller. . . For three days and three nights the column of gray, with 50,000 thousand bayonets and 50,000 lances, with gray transport wagons, … gray cannon, like a river of steel, cut Brussels in two.

Dan Carlin, Podcast Producer: He described the columns going on for days marching in perfect step with each other. And I think it was jaw-dropping. Many Americans are getting their first look at this through Richard Harding Davis’s writings.

Narrator: Davis arrived in the war zone mindful that his employers at the Wheeler News Syndicate expected him to hew closely to America’s strict policy of neutrality. But the news from Belgium turned more disturbing with each passing day. Racing to keep to their invasion timetable, the Germans ruthlessly put down any resistance. Civilians were mowed down with machine guns; 14,000 buildings were deliberately destroyed. Fifteen days into the invasion, German soldiers arrived at the Belgian city of Louvain, a center of culture for centuries. Then, they burned it to the ground.

Voice: Richard Harding Davis: At Louvain it was war upon the defenceless, war upon churches, colleges, shops of milliners and lace-makers: war brought to the bedside and the fireside; against women harvesting in the fields, against children in wooden shoes playing in the streets. At Louvain that night the Germans were like men after an orgy.

Narrator: Davis’ dispatches were hugely influential and they shocked Americans. They also crossed a line for his editors. “Wheeler cabled that the papers wanted me to be ‘neutral’ and not write against the Germans,” he wrote to his wife. “Fancy anyone being neutral in this war!”

Jay Winter, Historian: Six thousand Belgian civilians were killed. The Belgians would say murdered, in the course of the war, not one of them was a combatant. That was the price the German high command knew that they had to pay in order to get to Paris in forty-two days.

Narrator: In just a few short weeks, Richard Harding Davis had abandoned any pretense to neutrality. What his editors wouldn’t publish, he added to the preface of his book, which quickly became a best-seller.

Voice: Richard Harding Davis: Were the conflict in Europe a fair fight, the duty of every American would be to keep on the side-lines and preserve an open mind. But it is not a fair fight . . . [Germany] is defying the rules of war and the rules of humanity. . . . When a mad dog runs amuck in a village it is the duty of every farmer to get his gun and destroy it, not…lock himself indoors and toward the dog and the men who face him preserve a neutral mind. . . . A man who would now be neutral would be a coward.

Volunteers — Part One

Narrator: On August 25th, 1914, a hastily organized group of American volunteers set off through the streets of Paris for the train station. The men had just enlisted in the French army. Still wearing their rumpled street clothes, they hardly looked like soldiers. That didn’t bother the crowds whose cheers seemed to carry them along.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: There is a generation of Americans, particularly elite Americans who believed that with this elite status came the obligation to take risks for humanity. Now this was a totally romantic notion, but it inspired thousands of Americans to drop out of college, to quit their jobs. They felt a personal responsibility to address what was the largest human crisis of their times.

Narrator: Most of the well-heeled men were from elite colleges. Many of them had been drifting around Europe when the war broke out. There were painters and professors, medical students and mining engineers, a big-game hunter, a chef and a race-car driver.

Jennifer D. Keene, Historian: There are those Americans who believe that we should make an impact on the battlefield and with the government reluctant to do so, individuals decide to do so. We have a river of people crossing the Atlantic to join the allied army, to serve as ambulance drivers as aid workers, as nurses, as doctors.

Andrew Carroll, Writer: A lot of them truly loved France and they felt this was a war of civilization. They were after a kind of glory, even immortality. A real sense of wanting to sacrifice yourself for a greater cause.

Narrator: The French government was stunned by the wave of volunteers — more than 35,000, from 49 different nations. The newspaper Le Figaro called it “a moving homage, to which each people wish to contribute its part of courage and of blood.” Reinforcements were arriving in France just in time: the military situation was increasingly dire. The German army had swept through Belgium and was driving towards Paris. Every able-bodied man who could handle a rifle had been rushed to the front, including 5,000 French reservists who arrived in taxi cabs. The Americans’ parade was a response to France in her hour of need. At its head was a 26-year old Harvard graduate and aspiring poet named Alan Seeger, who had been living in Paris when war was declared.

Jay Winter, Historian: The notion of military service as a kind of a test of character, a test of…of courage…is a very deep American phenomenon, to test your mettle against the harshest steel in the world was something very hard to resist for people like Alan Seeger. And I think he was characteristic of a larger group of individuals who felt that this war was one that could lead them to experience things that other human beings won’t ever know.

Narrator: From their home in New York, Seeger’s parents did their best to reconcile themselves to the perilous path their son had chosen.

Voice: Alan Seeger: [Dear Mother:] I hope you see the thing as I do and think that I have done well . . . doing my share for the side that I think right . . . I am happy and full of excitement over the wonderful days that are ahead. It was such a comfort to receive your letter and know that you approved of my action. Be sure that I shall play the part well for I was never in better health nor felt my manhood more keenly. [Love to all, Alan.]

Narrator: Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion, a brigade famous for its ferocity and for taking in anyone willing to fight, and die, for France. In its ranks he met men like Victor Chapman, a fellow Harvard graduate who had given up his architectural studies in Paris to volunteer, and Eugene Bullard, who had escaped the brutal racism of Georgia by stowing away for Europe when he was seventeen. Once on the continent Bullard had worked as a panhandler, an actor in a traveling comedy troupe, and a boxer. The Legion put the Americans through a crash course in basic training, and they joined a war that now numbered millions of combatants on both sides. Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, who called themselves the Central Powers, were squared off against France, Britain and Russia, known as the Allies. Just as the American volunteers were learning how to be soldiers, the nature of the war shifted. After smashing their way through Belgium, the Germans were approaching the outskirts of Paris when their over-extended army gave out. Allied counter-attacks drove them back beyond the Marne river east of Paris. Both sides dug in for protection, and kept trying to outflank one another. Within weeks, an improvised network of trenches extended for more than 500 miles from the English Channel to the Swiss border. The war that all sides assumed would be over in a matter of weeks, now stretched on with no end in sight.

John Horne, Historian: The Germans realized that if they dig trenches and install their machine guns and artillery, the French and the British can’t get much further forward. [But] each side is trying to get the advantage. And in that process, which goes on for two months, what they’re really doing is learning that once they’ve dug trenches, once they’ve got defensive positions, they’ve invented a new industrialized form of siege warfare. And it’s stalemate.

Narrator: The “Western Front”, as it was called, consisted of deep gashes in the mud, dug in a zig-zag pattern to protect against enemy attacks. The lines were separated by a blasted landscape of shell holes, barbed wire, and decaying corpses known as No Man’s Land. The new fortifications provided protection from the murderous carnage of open warfare. But efforts to break out of the stand-off still sent hundreds of thousands of casualties flooding into hospitals just behind the lines. One of the nurses that struggled to cope with the onslaught was an American heiress from Chicago named Mary Borden.

Voice: Mary Borden: . . . . the hospital looks like an American lumber town, a city of huts, and the guns beyond this hill sound like the waves of the sea, pounding — pounding — and the sky is a-whirr with aeroplanes, and, sometimes, we are bombarded, and all the time troops and troops and more troops stream past. All day and often all night I am at work over dying and mutilated men. There is such a tremendous inflow of wounded that I can’t often sit down from 7 a.m. to midnight. Impossible to tear one’s self away from the men who are crying for a drink, whose blood is dripping in pools on the floor

Narrator: Despite its horrors, Alan Seeger and his fellow volunteers could not get to the front fast enough.

Voice: Alan Seeger: Dear Mother: we are actually going at last to the firing line. By the time you receive this we shall already perhaps have had our baptism of fire . . . . How thrilling it will be tomorrow and the following days, marching toward the front with the noise of battle growing continually louder before us. . . . The whole regiment is going . . . about 4,000 men. You have no idea how beautiful it is to see the troops undulating along the road . . . as far as the eye can see.

Pacifism

Song:

I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier,

I brought him up to be my pride and joy.

Who dares to place a musket on his shoulder,

To shoot some other mother’s darling boy?

Narrator: The most popular song in America in the spring of 1915 was “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier.” 700,000 copies — on 78 r.p.m. records, and as sheet music — flew out of stores. It was sung in bars and dance-halls, in concerts, schools, and in homes all across the country.

Richard Rubin, Writer: This was a time remember when in a city like New York, there were a great many daily newspapers being published. But an awful lot of the population didn’t read or didn’t read English. And they got their news from songs. You would go to your local saloon after work and there’d be somebody there playing a piano, singing a song about something that had just happened in the news. Songwriters would pick up a few newspapers on their way into the office in the morning. They would read stories and they would sit down and write a couple of songs about them before lunch. They’d be published by the end of the day and for sale on the street.

Song: Ten million soldiers to the war have gone,

Who may never return again.

Ten million mothers’ hearts must break,

For the ones who died in vain.

Narrator: America’s songwriting Mecca was a short stretch of West 28th Street in Manhattan. Known as Tin Pan Alley, it was home to one of the biggest industries in the country. Sitting around their upright pianos, songwriting duos were acutely conscious of the national mood.

Richard Rubin, Writer: “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier” was a mother’s plea for neutrality, it wasn’t just a catchy tune, it was what people were feeling.

Song: There’d be no war today, if mothers all would say,

“I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier.”

Narrator: Tin Pan Alley’s love affair with anti-war songs reflected the growing force and popularity of the American peace movement. In August of 1914, thousands of women, both black and white, had gathered together and marched down Fifth Avenue in silence. The Evening World reported that: “Every woman in the slow-moving line wore some badge of mourning, either a . . . band around her sleeve or a bit of crepe fluttering at her breast,” “as a token of the black death which is hovering over the European battlefields.”

Michael Kazin, Historian: The march is very silent, very somber. It’s sort of like a funeral march because they are mourning the young men who are dying in increasing numbers, after less than a month of war. The women’s march in 1914 really is the outgrowth of a very large women’s movement in America. And this is really a sign that women are going to be in the forefront of opposition to the war.

Jay Winter, Historian: Pacifism on the part of men was harder because it suggested cowardice. So women could say things and act politically in a way that men couldn’t.

Nancy K. Bristow, Historian: We could be the arbiter of wars. We could be those that would stop the killing. We could be those that would help find the peace.

Narrator: Woodrow Wilson’s own Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, was a committed pacifist, as was Eugene Debs, the leader of the American socialist party, who maintained that “the war in Europe is a crime against civilization.” The industrialist Henry Ford argued that only “two classes benefit by war – the militarists and the money lenders.” Meanwhile, the struggle kept offering up an appalling testament to the peace movement’s mission. In the first five months of the war, more than 300,000 Frenchmen were killed, 30,000 British soldiers, almost 150,000 Germans. Horrified by what the war had become, in April of 1915, a group of delegates from the Woman’s Peace Party set off for the International Congress of Women, in The Hague. The WPP numbered more than 40,000 women nationwide, and their goal was the creation of an internationally sanctioned framework for an end to the war. The president was Jane Addams.

Helen Zoe Veit, Historian: Jane Addams was in some ways the preeminent progressive. She founded a settlement house in Chicago called Hull House that was a place where immigrants and poor people could go to get help, to get education. She toured the country as a lecturer, in the name of peace. She was one of the most visible women in America at this time.

Narrator: “We do not think that by raising our hands we can make the armies cease slaughter.” Addams admitted, “[But] we do think it is fitting that women should meet and take counsel to see what may be done.” One of the peace movement’s harshest critics, former president, Theodore Roosevelt, lashed out at Addams and her fellow pacifists. “It is base and evil to clamor for peace in the abstract,” he thundered, “when silence is kept about concrete and hideous wrongs done to humanity at this very moment.” The women were undeterred. Roosevelt was a “barbarian”, they responded, “out of his element” and “half a century out of date. More than a thousand women, from 12 different nations, attended the conference, including representatives from Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Kimberly Jensen, Historian: Addams and women from many nations gathered to say war must end, and we must not engage in this conflict. The world has come too far to allow a barbarous war like this to happen and to really destroy what we have built. She saw alliances among women across national boundaries to be a very important pathway to peace.

Michael Kazin, Historian: The reason why Jane Addams and other pacifist feminists go to The Hague is to put pressure on Wilson to get involved in really backing up with actions what he’s been saying all along which is that it is the role of the United States to help mediate the war. And so in a sense this is a citizen’s peace initiative which is trying to nudge Wilson to do the right thing.

Narrator: On her return to America, Jane Addams met with Wilson six times.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: He hears from her about what she’s seen in Europe. And I think it clearly influences him by making him think that his instinct that America should have a leadership role in settling the peace is a correct one.

Narrator: “The time has come for intervention, and it is only by intervention that the war will be ended,” Addams argued. “Left to themselves, the warring nations will fight on and on. . . . [and] every day that peace negotiations are delayed will make terms of peace just that much harder.”

Lusitania

Narrator: On the first of May, 1915, an advertisement in New York newspapers announced the sailing for Liverpool of the British Cunard Line’s celebrated steamship, the Lusitania. Directly below the ad was a notice placed by the German Embassy. “Vessels flying the flag of Great Britain” it read, “or . . . any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters [adjacent to the British Isles] . . . . Travellers sailing in the war zone do so at their own risk.” The recent sinking of both cargo and passenger ships bound for England was evidence of the deadly seriousness of the German warning. Still, American tourists, prominent aristocrats, and English and Irish maids on the Lusitania decided to set sail.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: They were getting on the grandest ship of its day. The cruise ship from the era of the Titanic. And they thought no civilized nation would attack such a ship.

Narrator: What no one on board realized was how enmeshed in the war the Lusitania really was. The Germans saw the ship as part of a critical supply line supporting the British war effort. Like most of the freighters steaming toward England, the Lusitania’s hold was filled to capacity with American goods and raw materials.

Richard Rubin, Writer: Part of American neutrality from the very beginning was that American companies were free to do business with any of the combatants, on paper. But Britain had the world’s strongest navy and they used it to tremendous effect against Germany, instituting a massive blockade, which meant that all American armaments that were sold overseas were sold to the allies.

Jay Winter, Historian: Neutrality is almost always a fiction. In this case, the fiction was that the United States was neutral in word and deed. Nonsense. The United States tilted towards the allies from the very beginning.

Narrator: When war broke out, the U.S. economy was in the midst of a recession and Americans lost no time selling everything they could to the Allies. A typical British division of 18,000 soldiers required a staggering nine million pounds of ammunition, fodder and food each month. There was a seemingly bottomless market for barrels of beef, tons of iron and steel, bushels of oats and wheat. American companies also sold Britain and France massive quantities of bullets, artillery shells, and high explosives. The Germans desperately wanted to sink ships transporting these supplies. But since their Navy was no match for the British on the high seas, their only solution was to attack from under the surface.

Richard Rubin, Writer: The submarine was really a novelty before World War I. And all of a sudden this war comes along and it’s more than just a novelty, it’s an essential weapon. Western navies were unprepared to deal with it. They had no idea how to counter submarine warfare. It was unknown, it was unseen. You never knew where an attack was going to come from. And it terrified people.

Narrator: German submarines were technological wonders that were transforming the nature of warfare. Three months before the Lusitania set sail, the German High Command had launched a full-scale attack on ships entering the war zone around Great Britain, beginning a campaign that would send hundreds of ships to the bottom, including vessels flying the American flag. The captain and crew of the Lusitania dismissed fears of submarines, and encouraged passengers to enjoy the elegant amenities on board the 787-foot luxury liner. Vacationing couples on the lower decks enjoyed shuffleboard, while the wealthy travelers in first class were served high tea in the Verandah Café. From intercepted communications, the British knew the German submarine U-20 was lurking in the path of the Lusitania. Yet they chose not to send destroyers out to meet the ship and escort it into Liverpool. Within the halls of the British Admiralty, some argued that if the Lusitania was lost, it might precipitate American entry into the war.

Edward A. Gutiérrez, Historian: The British are definitely trying to get America involved in this war. Right from the beginning there is a sense of, we need you here. Your shipping is [not] going to be enough, we are your brethren, you must support us.

Narrator: On Friday, May 7th, as passengers excitedly scanned the horizon for their first sight of land, a torpedo hit the ship’s side. The explosion ripped a huge gash in the Lusitania. It took only 18 minutes for the leviathan to slide beneath the waves. For months after the Lusitania went down, dead bodies washed ashore. Hundreds of others were pulled lifeless from the Irish Sea, their corpses stacked on the docks. Many of the casualties could not be identified, and were buried in mass graves. In all, 1,198 men, women, and children were lost. 128 of them were Americans. The New York Sun called the sinking “premeditated and dastardly” and the Herald denounced it as “wholesale murder . . . on the high seas.”

John M. Cooper, Historian: What the Lusitania did was to bring the war home to Americans. Up to that time it was this awful thing that was happening to other people far away. Now the war had reached out and touched us. But what it did really was I think redouble an awful lot of people’s determination to stay out of it. The American media had been covering the war for months and months now. We knew what it was like. Americans had been imagining their sons at the battlefront. We don’t want to buy into that. And here is this act of barbarism that’s threatening to bring us in.

A. Scott Berg, Wrtier: Much of America is now beginning to discuss what should America’s role be in this war, now that we are losing lives? How do we maintain a position of neutrality?

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: The Lusitania sinking creates a crisis within the Wilson administration, in part because it reveals that this public and official face of neutrality was actually no such thing.

Narrator: Germany argued that the speed with which the Lusitania was sent to the bottom was proof that it was loaded with tons of ammunition for the Allies.

Richard Rubin, Writer: It was suggested that the torpedo struck the boiler but a boiler wouldn’t blow up with that kind of force to sink a liner of that size in 18 minutes.

A. Scott Berg, Writer: The Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who was a great pacifist, he said the one thing I want to know is, were there in fact arms on that ship? And the truth of the matter is, there were arms on that ship.

Adriane Lentz-Smith, Historian: Actually from the German side, not an irrational or indefensible act. In some ways you have these two visions of what is a legitimate act of violence, just sort of colliding and not being able to reconcile themselves.

Jay Winter, Historian: How far can you tolerate the deaths of American citizens is a very legitimate question today, as it was a hundred years ago. And I think being the man who protects American lives on the one hand and on the other hand protecting American lives by not going into war, presented [Wilson] with a very difficult high wire act. And I think he understood that that meant the Lusitania wasn’t going to be the last.

Narrator: Wilson responded to Germany’s provocations with a series of diplomatic messages to Berlin, warning that if aggression continued, America would consider it an act of war. In protest, William Jennings Bryan resigned. But the president’s threats worked. The German government pledged to put limits on their submarine warfare.

Alan Axelrod, Writer: For those who were strong advocates of neutrality it was too stern and for others such as Teddy Roosevelt, it was an ignominious, cowardly kind of weasely way out of avoiding a fight.

Michael Neiberg, Historian: The Lusitania forces the American people to recognize that just having two oceans protecting you doesn’t mean you’re protected from danger. Doesn’t mean you can go on with business as usual. And the Lusitania opens up that debate. What should we do about this?

Narrator: Three days after the Lusitania was sunk, in front of a crowd of 15,000 people in Philadelphia, Woodrow Wilson tried to reaffirm America’s neutral role in the conflict. “The example of America must be the example not merely of peace because it will not fight, but of peace because peace is the healing and elevating influence of the world . . .” he declared. “There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right.”

Wharton

Voice: Edith Wharton: Since leaving Paris yesterday we have passed through streets and streets of such murdered houses, through town after town spread out in its last writhings . . . deliberately erased from the earth. At worst they are like stone-yards, at best like Pompeii. But Ypres has been bombarded to death, and the outer walls of its houses are still standing, so that it presents the distant semblance of a living city, while near by it seems to be a disemboweled corpse. Every window-pane is smashed, nearly every building unroofed, and some house-fronts are sliced clean off, with the different stories exposed, as if for the stage-setting of a farce . . . and with a little church so stripped and wounded and dishonoured that it lies there by the roadside like a human victim.

Narrator: In the spring of 1915, one of America’s most famous novelists embarked on a tour of the Western front. Edith Wharton had come on her own initiative to deliver medical supplies, take photographs and write letters and articles for publication back home about what she called the “dreadful realities of war.” For seven months, Wharton followed the track of the German invasion, describing the “huge tiger scratches that the [German] Beast flung over the land.” She stopped to visit French troops, who wrote “Vive L’Amérique!” in chalk on her car, and got close enough to the front lines to peer out at a dead German soldier sprawled across No Man’s Land. “I had the sense of an all-pervading, invisible power of evil,” she remembered, “a saturation of the whole landscape with some hidden vitriol of hate.”

Michael Neiberg, Historian: Edith Wharton is symbolic of a lot of Americans who are living in France, already had a deep passion and interest in France, a deep love of France. They’re able to make clear exactly what’s happening. And the important thing about this is it’s coming from an American voice.

Narrator: At the outset of the war, Wharton had organized a series of American hostels to shelter the wave of dislocated families pouring into Paris. In little more than a year, her relief organization had provided clothing and jobs for more than 9,000 refugees and served nearly a quarter of a million meals. She also begged Americans at home to help finance her efforts. “For heaven’s sake . . .” she wrote to a friend, “proclaim everywhere, and as publicly as possible . . .what it will mean to all that we Americans cherish if England and France go under.” In June, Wharton arrived in Dunkirk immediately after the town had been shelled by the Germans. The “freshness of the havoc seemed to accentuate its cruelty,” she wrote. The hospitals in Dunkirk were struggling to absorb the casualties from artillery, but they were also confronting the effects of a shocking new weapon that had just been introduced. A month before Wharton had arrived, not far from Dunkirk, French and Canadian troops had looked across No Man’s Land and seen a greenish haze drifting towards them. Soon the unsuspecting men were writhing in agony, choking to death as chlorine gas burned their throat and lungs. In a panic, the survivors abandoned their positions. More than a thousand soldiers were killed, most of them slowly drowning as their lungs filled with fluid.

Helen Zoe Veit, Historian: World War I used a combination of really traditional fighting techniques with all these brand new technologies that turned traditional battle into slaughter or things like poisonous gas which seemed like this insidious and unpredictable new weapon that just killed indiscriminately, that had nothing to do with individuals fighting each other and that was really just about mass death.

Dan Carlin, Podcast Producer: Gas was something that was a new horror. And for people that already thought that the Germans were evil personified, it just played in to those sorts of attitudes.

Richard Rubin, Writer: Gas in a way was as terrifying to people as the submarine. Gas could blind you, very quickly. It could make you cough up blood very quickly. It could break down your lungs very quickly.

Dan Carlin, Podcast Producer: Eventually both sides would use gas. It would just be part of something that was a descent into 20th Century warfare. And so gruesome. And truthfully to take things to a level that had never been seen before.

Narrator: Edith Wharton wasn’t shy about telling the world what she thought of the German army’s tactics. “The ‘atrocities’ one hears of are true,” she wrote in a letter “I know of many, alas, too well authenticated. . . . It should be known that it is to America’s interest to help stem this hideous flood of savagery by opinion if it may not be by action. No civilized race can remain neutral in feeling now.”

Andrew Carroll, Writer: Edith Wharton really wanted to create kind of a sympathetic character in the French people and in France itself and she was even accused by some of her fellow authors of being a propagandist. But she was writing in a way that I think she knew would have as powerful an effect as possible. I think she was changing the tide of how people viewed the war and whether America should at long last get involved.

Dan Carlin, Podcast Producer: The way that German atrocities were played up in the media helped create a good guy-bad guy scenario. This is the idea of the Germans as Huns, as destroyers, as barbarians.

Jay Winter, Historian: The moral depravity of German soldiers suggested a moral cause. It made it about the sons of light against the sons of darkness. It became a sacred bill of indictment against them for behavior of a kind that no one could justify.

The Poison of Disloyalty

Narrator: On the morning of July 3rd, 1915, an intruder holding two pistols barged into the Long Island mansion of America’s most powerful banker, J.P. Morgan, Jr. In the ensuing struggle, the attacker was subdued, but not until he wounded Morgan twice in the thigh. The gunman turned out to be a former German teacher at Harvard, who had set off a bomb at the U.S. Capitol the day before. Although no direct link to the German government was proven, the attack on Morgan appeared to be part of a larger effort by Germany to stop American support for the allies.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: If you sympathized with Germany then Morgan was your ultimate enemy. And because he was so powerful as an individual, it was actually possible to believe that assassinating him could actually stop the war.

Narrator: As the conflict dragged on, the French and British had required larger and larger loans to keep themselves afloat. Morgan, a committed Anglophile, had been more than happy to oblige. He also served as a purchasing agent, helping to procure the millions of pounds of food and armaments the Allies required every month. President Wilson turned a blind eye to this financial lifeline to the Allies. Morgan would eventually secure a $500 million dollar line of credit for the French and British — the biggest foreign loan in Wall Street history.

Jay Winter, Historian: The war turned the United States into a creditor power, not a debtor power, for the first time in its history. That’s a big argument. We’re in the war and we have an economic interest to make sure that the allies win it.

Dan Carlin, Podcast Producer: It’s not just the fact that the U.S. is loaning money to the allies, but that they’re spending it in the U.S. for stuff so all of a sudden hiring picks up, manufacturing picks up. Americans were working again, and nobody wanted to cut that off.

Richard Rubin, Writer: Our economic support for the allies started out at the very beginning of the war and quickly became a vicious cycle. Because we could only sell to the allies, they became our main market. Because the allies could only buy from us, they quickly became indebted to us. And so it was in our best interest to send them more armaments so that they could win the war. Great Britain during the war spent fully half of its war budget in the United States of America.

Narrator: The attack on J.P. Morgan drew attention to the nation’s largest ethnic group, German Americans.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: German cultural life was everywhere. There were German churches, German language newspapers. German was the most commonly studied foreign language in American high schools. What we now call classical music was German music, Bach, Beethoven and Brahms played by symphonies, sung by ordinary people in choirs and in churches. They were particularly visible in certain parts of the country, particularly the Midwest, [and] they wielded enormous political power in some cities like St. Louis, Cincinnati, Milwaukee.

Narrator: In response to what they saw as a hypocritical and blatantly one-sided neutrality policy, the National German-American Alliance — which boasted more than 2 million members and chapters in 44 states — held mass demonstrations calling for an arms embargo. Former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan was their featured speaker. The American Women’s League for Strict Neutrality collected over one million signatures — written on a scroll more than 15 miles long — endorsing an “embargo on the things which kill.” While many of the nation’s leading magazines and newspapers clearly sided with the Allied cause, the German-American magazine The Fatherland promoted what it called “fair play for Germany and Austria-Hungary.” But the paper was fighting an uphill battle. In the first days of the war, the British had cut the transatlantic cables connecting America to the European continent. The only remaining cable was from London.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: Now this may not sound like much, but what it means is that all the news that Americans get about the European war is coming through Britain over British cables which means from the very beginning they’re getting one side of the story and so if there is one single event that the British do to guarantee that the Americans will not be really neutral, it’s that action.

Narrator: Increasingly frustrated by the one-sidedness of American neutrality, the German government began to fight back. Only a month after Morgan’s close call, in New York, a German diplomat’s briefcase fell into the hands of American officials. They were shocked at what they found inside. The Germans were secretly supporting newspapers sympathetic to their side, paying corrupt union leaders to stage strikes, and setting up shadow companies to disrupt the munitions trade. They had even planned a coup in Mexico that would bring a pro-German strong-man to power. The raft of incriminating evidence revealed that Germany was willing to risk almost anything to undermine America’s support for the Allies. Sensational exposés in the American press fanned hysteria about German subversives. Soon, almost any accident or strange occurrence was attributed to Berlin. The mounting paranoia began to implicate German-Americans as well. Even the president took up the theme. In a speech to Congress in December 1915, Wilson warned that, “There are citizens of the United States . . . born under other flags . . . who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life. . . . Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out. . . . They are infinitely malignant, and the hand of our power should close over them at once.”

Michael Neiberg, Historian: What Wilson is really trying to do is say, look, if you’re German, if you stand with us, you’re okay. But if your loyalties are on the side of the Europeans, then we have a problem.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: This is a criticism of political radicals, anarchists and others. But he frames it not as a political opposition, but an ethnic one, that these are ethnic outsiders, they’re immigrants, they’re not Americans. And by doing this he’s making it possible for Americans to see their immigrant neighbors as threats to national security.

Narrator: Eight months after Wilson’s speech, two fires broke out on the small island of Black Tom in New York Harbor. The island was a railroad yard and munitions depot where two million pounds of armaments, bound for the Allies, were being stored. The detonation shattered windows in downtown Manhattan, lodged shrapnel in the Statue of Liberty, and was heard as far away as Philadelphia. If it had been an earthquake, the blast would have measured 5.5 on the Richter scale. “I am sure . . . the country is honeycombed with German intrigue and infested with German spies,” Wilson wrote to one of his advisors, “the evidence of these things [is] multiplying every day.”

Volunteers — Part Two: Lafayette

Voice: Victor Chapman: Dear Uncle: The state of filth I live in here is unbelievable, and the barest necessities are luxuries. I get down to the depot and kitchen about every two days for a face wash. Our heads get crusted with mud, — eyes and hair literally gluey with it.

Narrator: After enlisting in the Foreign Legion, Victor Chapman had spent twelve months at the front. It was a long way from architecture school in Paris. Sanitation in the trenches was crude or non-existent. When it rained, the trenches became rivers of mud. Soldiers were tormented by lice, which the British called “Cooties,” and an infection known as “trench foot.” To escape the rain of high-explosive shells, soldiers constructed dugouts as far underground as possible. The men yearned to test themselves in open battle — anything to interrupt the tedium, and the random visitation of death. All up and down the lines in the spring of 1916, the great struggle that soldiers talked about was at Verdun. At that ancient fortress town the French had made a stand against a massive German offensive. The contest had descended into a sickening battle of attrition, grinding on, month after month, with no end in sight. “I hope you got my letters . . . about my not being at Verdun,” Alan Seeger wrote home, “This ought to have been a comfort to you. Of course, to me it is a matter of great regret and I take it as a piece of hard luck.” Meanwhile, Eugene Bullard longed to be anywhere but Verdun. Bullard had been transferred to a new French unit that had seen heavy fighting, but he had never experienced anything like this.

Voice: Eugene Bullard: Neither side knew where the lines were and there were no more trenches and everything was guesswork. In those hours every man at Verdun either got one more hole in him than he was born with or, if he was lucky, he ducked into a series of shallow shell holes as I did.

Narrator: Bullard was manning a post with a machine gun as a mass of Germans came on.

Voice: Eugene Bullard: It was like mowing grass . . . only the grass grew up as fast as you mowed it . . . You’d mow them down, and four more would be in their places. . . . you could see ’em wriggling like worms in the bait box. . . . Every time the sergeant yelled, fire! I got sicker and sicker. They had wives and children, hadn’t they?

Andrew Carroll, Writer: So this young boy from Georgia, ends up in what is the most horrific battle of World War I. And Bullard made a comment. He said he wasn’t surprised by how many people were killed at Verdun. He was surprised that anybody got out of it alive at all.

Narrator: Bullard was wounded twice at Verdun. He would become one of the first Americans to receive the French military honor for exceptional bravery — the Croix De Guerre.

Voice: Victor Chapman: Dear Papa: This flying is much too romantic to be real modern war with all its horrors. There is something so unreal and fairy like about it, which ought to be told and described by Poets.

Narrator: High above the blackened battlefield, Victor Chapman had escaped the trenches and found himself engaged in a new kind of war, one that had never been waged before.

Andrew Carroll, Writer: It’s really I think difficult to understand today how exhilarating flight was back a century ago. The planes were made of practically nothing. They would fall apart just almost you know at a whisper. But there was something very visceral about it, because you were in total control. You didn’t even have the windscreen in front of you. I mean you’re feeling the blast of air. You’re dodging through clouds. You’re looking at the sun. You see the curve of the earth. You know humans had gone up in balloons before, but that was the extent of flight. This was really flying.

Richard Rubin, Writer: If you see these airplanes today, you wonder how anyone in their right mind went up in them. They were essentially bicycles with wings. Very, very frail. And this was very dangerous work.

Narrator: From the outset of the war, both sides raced to turn the airplane to their advantage. Pilots began as observers, and took thousands of photographs of enemy positions. They tried mounting machine guns on the wings, but had to fly with one hand while shooting with the other. Eventually machine guns were synchronized so they could fire through the propeller, and pilots engaged in vicious duels, known as dogfights. With each innovation, the death toll kept rising. Chapman joined a small group of American volunteers flying for France. They called themselves the Lafayette Escadrille, and they were the first all-American unit to fight for the Allies.

Richard Rubin, Writer: The Lafayette Escadrille wasn’t a cross-section of American society. They were very well educated young men who wanted to fly for France. And so they just went over and did so. Even though this officially violated American neutrality in that war there was sort of a winking arrangement with that. You know, don’t ask, don’t tell.

Narrator: The danger of their new occupation helped cultivate an air of reckless bravado among the pilots of the Escadrille. “If I should be killed in this war,” one of Chapman’s fellow pilots wrote home, “I will at least die as a man should.”

Michael Neiberg, Historian: They throw outlandish parties. They have two lion cubs, Whiskey and Soda, as their mascots. Celebrities from all over Europe want to have dinner with them, want to see them. So they have this devil-may-care attitude. They don’t really need the French army’s discipline. The French army needs them more than they need the French army. They fly in their bathrobes. They do more or less whatever they want.

Narrator: The Lafayette Escadrille made headlines in the United States and an American film crew arrived in France to chronicle the exploits of Victor Chapman and his fellow aviators.

Voice: Victor Chapman: Dear Father, [We] roared and buzzed . . . past the camera man, up into the air. Then one at a time we rushed by him. I must say that he had nerve. . . You will see it all, I expect, sometime this summer; for it is to be given to some American cinema company in Paris

Andrew Carroll, Writer: They’re very popular and regardless of what Americans felt about the war itself, these guys were in a way heroes. They were kind of like the early astronauts.

Narrator: For all their fame, and often reckless bravery, the pilots of the Lafayette Escadrille understood that the odds against their survival were daunting. On June 23rd, Victor Chapman dove into a dogfight, trying to rescue some of his comrades. He shot down three German planes, before being overwhelmed, his plane riddled with bullets. He became the first American flier to give his life for France. A French friend of the Chapman’s wrote to Victor’s father shortly after his death. “I have just left the Church . . . after attending the service in honor of your son… The self sacrifice of this one who comes to us, and places himself at our side, for no other reason than to make right triumph over wrong, is worthy of . . . honor. America has sent us this sublime youth, and our gratitude for him is such that it flows back upon his country.”

Richard Rubin, Writer: They were handsome, well-bred young men who went off to do what they thought was right, even though the United States didn’t want to get involved in the fight at that point. And they were flying airplanes which captured the imagination of the entire world. To this day, the image that we think of often when we think of World War I is an aviator with his goggles and his leather cap and his long silk scarf. They were a very tiny minority of any fighting force. But they were, in essence, the face that all the armies wanted to show the enemy and the world.

Preparedness

Narrator: As American volunteers were fighting and dying in France, some of their countrymen at home were arguing that the United States must be ready for war. Championed by people like Theodore Roosevelt and the former chief of staff of the army, what was known as the Preparedness movement, had come into its own in the small town of Plattsburgh, New York in the summer of 1916. For five weeks, more than 1,300 young men played at being in the army. New York City’s mayor and commissioner of police took part, as did the coach of the Harvard football team.

Richard Slotkin, Historian: They were living in barracks, they were living in tents, they were doing physical training. They did a lot of work on the rifle range because Roosevelt believed that marksmanship was the key to everything. His idea of an officer was someone who combined the skills of a hunter and a scout with the skills of a commander.

Dan Carlin, Podcast Producer: These camps were almost like Boy Scout camps in a sense. I mean you got your friends and your football team. And this idea that we’re going to go and prepare ourselves for war is both naïve when you think about the difference between what these camps must have been like compared to what troops facing gas on the Western Front were dealing with. And yet at the same time, there was something very American about the whole idea too.

Michael Kazin, Historian: The main supporters of preparedness believed the United States had to be prepared to fight against Germany. Also they believed that a strong nation had to have a strong military. And young Americans had to have a military mindset. So training, knowing how to use a gun, knowing how to conduct oneself in combat, these were important skills for any advanced, powerful nation to have.

Narrator: The Plattsburg Ivy Leaguers weren’t the only ones who saw the value of military service. The African-American community had long argued for all-black National Guard units that they felt would prove their patriotism and advance their political power. As the Preparedness movement gained momentum, black leaders in Harlem at last succeeded in commissioning their own regiment, and began to recruit men from New York city to bring it up to full strength. On May 13th, some 150,000 supporters of preparedness turned out to walk up Fifth Avenue. They passed under the largest flag in the country, strung between the St. Regis and Gotham hotels. There were grocers and lumbermen, corset-makers and firemen, the American Woman’s League for Self Defense, and the Lower Wall Street Business Men’s Association. African-American groups petitioned to be included in the procession, but were turned down. Twelve thousand marchers passed the grandstand every hour. Lasting almost the entire day it was the biggest parade in American history. Across from the reviewing stand was a storefront with a sign that read “War Against War.” It was the work of Jane Addams and her Woman’s Peace Party, representing an “Anti-Preparedness” movement that numbered up to 80,000 members nationwide. Their star attraction was a fifteen-foot model of “Jingo the Dinosaur,” mounted on a truck, with a sign that declared: “This animal believed in huge armament. He is now extinct!” Despite the use of political theater by the Women’s Peace Party, by the summer of 1916 the Preparedness movement was gaining such notice that major magazines began to endorse it. Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper decided to feature it on its cover, with the headline “What Are You Doing for Preparedness?” They asked the illustrator James Montgomery Flagg to come up with an image for the new issue.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: He was a very prolific artist, but he was also a bit of a procrastinator. And he was on a very tight deadline. And so he had no model to use. He had seen some other posters that had been published in Britain and Uncle Sam as an image had existed throughout the 19th Century, dates back even to the revolution by some measures, so [Flagg] had a mirror and his own reflection that he used to develop a new image. He added some whiskers, some gray hair. Added a top hat and with that the iconic image for Uncle Sam was born.

Election of 1916

Song:

I think we’ve got another Washington

Someone who’s just as good as he can be

He’s called the man of peace

No matter where he goes

He’s just the one for me

It takes a little time for him to make up his mind

But he gets there just the same

I think we’ve got another Washington

And Wilson is his name.

Narrator: Looking ahead to the presidential election in the fall of 1916, Woodrow Wilson confronted the fact that his prospects were far from favorable. For more than two years he had kept America out of the Great War. Now, the national mood was restless. German spies seemed to be everywhere, and U-boats still prowled the Atlantic. The war continued to be big business, and the economy was booming. But millions of German-Americans actively campaigned against the President, arguing that neutrality was a sham, and that America was blatantly supporting the Allies. What support Wilson did have was drawn from people’s sense that he had done everything he could to keep them safe from the European bloodbath.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: Wilson is riding along a sort of knife edge and the war becomes one of if not the central issue in the presidential contest. And this yields the, the slogan, “He kept us out of war.”

Narrator: The slogan seemed to be working, but it worried the President. “Any little German lieutenant can push us into war at any time by some calculated outrage,” he told his Secretary of the Navy. Wilson’s Republican opponent in November was a popular Supreme Court Justice, Charles Evans Hughes, whose position on the issues was often overshadowed by the former Republican president, Theodore Roosevelt. Wilson displayed “culpable weakness and timidity,” thundered Roosevelt, “It is our purpose this fall to elect an American president, and not a viceroy of the German emperor.”

Michael Kazin, Historian: Teddy Roosevelt’s been attacking Woodrow Wilson nonstop for over a year. So even though Hughes says he wants the U.S. to stay neutral, a lot of Americans don’t quite believe it. And so the peace movement, which has been ambivalent about Wilson up to now, jumps in and says, we have to support Wilson now, he’s our best bet to keep the nation at peace.

Narrator: Anxious to cultivate the influence of the peace movement, Wilson sent Jane Addams five dozen long stem roses, and asked for her endorsement.

Michael Kazin, Historian: Addams is a life-long Republican. And so it’s a big step for her to support Wilson. But she believes that Wilson is certainly a peacemaker. He wants to be a peacemaker she believes. She wants to give him a chance to be a peacemaker, where she has no trust whatsoever in the current leadership of the Republican Party.

Narrator: As the campaign picked up speed in the fall of 1916, Wilson often appeared with his most fervent supporter by his side: his new wife, Edith Bolling Galt. They had met the previous spring, only two months before the crisis over the sinking of the Lusitania.

A. Scott Berg, Writer: He was driving the streets with his doctor and closest friend at that time, who waved hello to this woman on the street. And Wilson suddenly turned and said, who is that beautiful woman?

Narrator: Edith Galt was a vivacious, well-to-do Washington widow. Wilson would spend the next six months trying to win her affection.

A. Scott Berg, Writer: It took up a lot of his time, maybe it took up too much of his time. . . . He was bewitched. There were days he was writing three or four love letters to her.

Narrator: “You have invited me to make myself the master of your life and heart,” the President wrote, “the rest is now as certain as that God made us.” “This is my pledge, Dearest One,” she replied. “No matter whether the wine be bitter or sweet we will share it together and find happiness in the comradeship.”

A. Scott Berg, Writer: Edith Galt had this incredibly tonic effect on the president. He came to life again. And it allowed him really to focus on his work with so much more ease. And he had somebody to share all this with. She knew part of the job of being Woodrow Wilson’s wife was to be a great promoter, was to be out there rooting for him and, and supporting him.

Narrator: With the nation so deeply divided, the presidential race remained close. In the end Wilson barely won a second term.

Christopher Capozzola, Historian: It’s a razor thin margin. Wilson really wins with a squeaking victory through a couple of western states, where if the vote had gone just slightly in the other direction, Charles Evans Hughes would have been president.

Jay Winter, Historian: The election of 1916 was in good part a referendum on the war and the Wilson balancing act of what I would call neutrality with a tilt. The idea that the country was not going to [make it its mission to end the war] was attractive. On the other hand, the notion that the United States had many interests in common with the allies, that makes sense.

Narrator: For the moment, Woodrow Wilson had held together the slender consensus that he was the best man to guide America through a dangerous world. Still, he sensed that his nation might not be able to remain on the sidelines forever. “We live in a world which we did not make, which we cannot alter, which we cannot think into a different condition from that which actually exists,” the president declared “It would be a hopeless piece of provincialism to suppose that, because we think differently from the rest of the world, we are at liberty to assume that the rest of the world will permit us to enjoy that thought without disturbance.”

Volunteers — Part Three: Seeger

Narrator: As the bloody year 1916 drew to a close, Americans were transfixed by the scale of the suffering that had been unleashed on the European continent. Two epic battles, at Verdun and along the river Somme, had raged on and on. When they were over, the strategic balance of the war remained virtually unchanged.

Jay Winter, Historian: The battle of the Somme, [was] Britain’s attempt to break through the German lines in the north of France by sheer industrial power. It’s the first battle in history with one million casualties. But I do believe that the two battles changed the meaning of the word battle. They were so big that they crossed the threshold of suffering.

Alan Axelrod, Writer: The war became a war of attrition such as the world has never seen. It became a war of two powers annihilating one another. How do you understand that? How do you write about that? How do you explain that? How do you do anything but recoil in horror from that because it makes no sense? As one young French lieutenant said at the battle of Verdun, humanity must be mad to do what it’s doing. And it’s true, what other answer was there?

Narrator: At a hospital near the Somme battlefield, the American nurse Mary Borden often met the procession of ambulances and their cargo of grievously wounded soldiers.

Voice: Mary Borden: There are no men here, so why should I be a woman? There are chests with holes as big as your fist, and pulpy thighs, shapeless; and stumps where legs once were fastened. There are eyes — eyes of sick dogs, sick cats, blind eyes, eyes of delirium; and mouths that cannot articulate; and parts of faces — the nose gone, or the jaw. There are these things, but no men; so how could I be a woman here and not die of it? Sometimes, suddenly, all in an instant, a man looks up at me from the shambles, a man’s eyes signal or a voice calls “Sister! Sister!” Sometimes suddenly a smile flickers on a pillow, white, blinding, burning, and I die of it. I feel myself dying again. It is impossible to be a woman here. One must be dead.

Narrator: One of the millions of men caught up in the fighting at the Somme was Alan Seeger. In late June, he and the rest of his division from the French Foreign Legion were moved into position outside the heavily defended village of Belloy-en-Santerre.

Voice: Alan Seeger: June 28th 1916: We go up to the attack tomorrow. This will probably be the biggest thing yet. We are to have the honor of marching in the first wave. I will write you soon if I get through all right. . . . I am glad to be going. If you are in this thing at all it is best to be in to the limit. And this is the supreme experience.