Issue of the Week: Human Rights, War, Disease, Hunger, Population

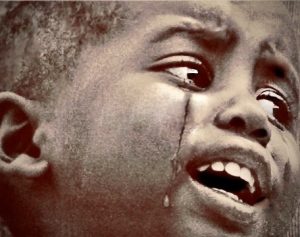

Aftermath of Rwandan genocide, Planet Earth Foundation (c) 1996-2019

After every genocide, Never Forget, or Never Again are heard and seen over and over.

Until they aren’t.

International Holocaust Remembrance Day was last Sunday, January 27.

You read all about it, you remembered, right?

We don’t think so. Even with decades of focus dedicated to never forgetting.

2019 is the 25th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, where about one million people were killed in one hundred days.

Everyone from the United Nations to the White House to every government on the planet in varying degrees of capacity and responsibility said, increasingly in the aftermath:

We should have done far more, intervened, stopped it–and could have–first before it started, but also after it did.

The origins of the genocide and the impact since, in Rwanda, in Africa, and globally in terms of the issues that cause such crimes and suffering are wrapped up in fear of who will survive and thrive and who will not, colonialism and its aftermath, the ongoing dynamics of power and inequality, lack of guarantees of basic needs and human rights for all.

We produced a public service campaign in part to support NGO work to provide aid in the aftermath of the genocide.

If there is a genocide still fresh and seared into our consciousness, this is it, right?

We’ll let you answer that for yourself.

Bosnia was happening at approximately the same time, over a longer period. The children there were wondering where the world was when they and the adults were dying there too. At least help finally came, stopped it, and averted a wider, longer conflagration.

Darfur has happened since, Iraq with different offenders over decades, and others, Myanmar in recent years, in and out of conscousness.

And Syria, the centrifugal force of Hell, for years and still, but the global silence is now nearly complete. And the global price continuing.

Rwanda, however, was stamped on public consciousness as a kind of archetypal genocidal rampage with so many slaughtered so viciously and quickly.

The story of the genocide, what preceded it, what has happened since, the applications from locally to globally for basic needs and rights being provided and the complexity and struggles around implementing international law in what has become one world whether we like it or not–we leave these issues to the reader to thoroughly explore.

Here, we’ll let a film series and articles do the initial educating.

A new series on Netflix in partnership with the BBC, Black Earth Rising, a fictional rendering of the events is not to be missed. It started on Netflix Friday.

It ranges from brilliant to flawed and it makes no difference–it takes you from then to now in numerous critical ways. Start watching or streaming as soon as you finish here.

There isn’t a major issue facing the planet, then and now, that wasn’t and isn’t part of this tragedy.

Following are two reviews of the film from NPR and IndieWire. Then an interview with lead Michaela Coel in ESPN W on being a survivor of sexual assault, the pressure not to speak out, her refusal to conform to (often sexist) fashion standards that stifle natural strength and beauty, and being the youngest person and first black woman to present the MacTaggart Lecture at the annual Edinburgh International Television Festival in its 43-year history.

Lastly, there is an informative and deeply moving article on survivor testimonies from the genocide in The Walrus Magazine.

Here they are:

Steve Green, IndieWire, Jan 26, 2019

Michaela Coel and John Goodman are riveting in this tale of a woman searching for answers about how she survived the Rwandan genocide.

Whether it’s a self-fulfilling storytelling prophecy or a dangerous by-product of the way geopolitical developments have been viewed for the last few centuries, stories told on an international scale often end up loaded with allusions to chess. Particularly in stories drenched in spy maneuvering and intelligence gathering, referring to a game of pawns and rulers and thinking a half-dozen moves ahead has become apt, if not obligatory.

For better or for worse, that’s how writer/director Hugo Blick frames much of the story of “Black Earth Rising.” (He also closed the credits sequence of his previous TV venture, the 2014 limited series “The Honourable Woman,” with a queen piece dropping in slow motion.) But for as much as “Black Earth Rising” charts the story of reconciling trauma as a tactical game, there’s an overarching condemnation of the ways that different forces on a global stage, from imperial powers to massive multinational corporations, treat widespread tragedy as a simple step in an unfolding narrative.

“Black Earth Rising” centers around the evolving experiences of Kate Ashby (Michaela Coel), a legal investigator drawn into an international diplomatic conflict by virtue of both her family and her past. Her adoptive mother Eve (Harriet Walter) takes the lead on an unfolding war crime prosecution, one inextricably linked to the Rwandan genocide that Kate survived as a small child. As the ripples begin to emanate out from this single case, an American expat barrister Michael Ennis (John Goodman), helps guide Kate through a murky sea of foreign policy calculations and dormant secrets.

In the process, “Black Earth Rising” interrogates the idea of collective memory and what gets preserved for future generations. As form matches subject, one tragedy built into the series’ framework is a changing perception of the truth. Decades’ worth of context changes with the arrival of a single photograph, and the violent silencing of one voice strips vital knowledge from everyone else’s understanding. The series gives Kate a delicate and precise task, asking her to balance the pursuit of information around a mass slaughter with the truth of her past and the stability of Rwanda’s future.

Blick counteracts the dense, meticulous nature of some of these legal proceedings and diplomatic procedures by bolstering the human part of the engine driving the story. Haunting animated sequences accompany memories from the genocide itself, paired with images of the aftermath to present an indelible window into the devastation of unspeakable crimes. Though some cracks in this mystery come in the form of physical objects, breakthroughs in Kate’s understanding of her own history come in the form of stories told by everyone’s remembrances of a time some would rather keep hidden.

“Black Earth Rising” manages to show how the fate of entire groups of people are often determined by men sitting across an office table from each other, discussing abstract consequences with the same care as they would dissecting the efficacy of the Queen’s Gambit. Yet Blick isn’t blind to the inherent horror within that concentration of power and the sadness that the arc of justice can be determined by trading favors and settling personal scores.

Blick’s work follows in a literary tradition of interwoven narratives, playing out across decades and continents. While it’s fascinating to see those machinations work their way toward a conclusion, occasionally a few dashes of cleverness oversell his hand. (A few quips about famous poems and even a line from “West Side Story” wind their way in to spice up some interdepartmental dialogue.) But when “Black Earth Rising” cuts past its own occasional glaze, Blick arrives at some stark foundational truths about the way that individuals — and sometimes entire nations — process grief and guilt.

Through Kate and Michael’s various interactions with others involved in this search and prosecution effort, “Black Earth Rising” shows how raw emotions can mutate into unexpected feelings and actions. Coel plays Kate’s psychological journey with an impressive range, simmering when having to maintain composure in the face of an insulting barrage of questions, and allowing decades’ worth of pain to boil over when confronted with new information about what’s been locked away all that time.

As Michael becomes another conduit for what ties these at-times-disparate storylines together, Goodman injects a real sense of empathy to combat the encroaching brutality and cynicism. Where there’s humor to be found, Goodman brings it to the surface with unexpected, understated care and warmth. As the series progresses and the full extent of the weight both of these characters have carried comes into focus, it gives retroactive depth to interactions and comments that at first seemed far more simple.

For as much as a few of the series’ fictional news broadcast feel engineered to help the various characters in this story play catch-up, Blick shows an admirable restraint elsewhere. He has a knack of turning each audience member into something of a detective, introducing key details via misdirection, but with enough clarity for viewers to retroactively piece together the tiny clues laid out along the way.

“Black Earth Rising” confronts what humanity is capable of, in all its many forms. There are unspeakable atrocities, acts of perseverance, gestures of grace and understanding. That all extends to an impressive array of supporting players, spanning from Washington D.C. to the heart of the African continent. They all serve a function within the story, but the show avoids reducing them to that purpose. Even the most ruthless individuals have a weakness, and the most pure-intentioned can fall prey to an honest mistake.

Blick is in visual control of the story. When various characters cross a line, the camera makes that metaphorical act literal. The eight-part runtime gives him a chance to let some moments breathe longer than a normal story of this kind, as when a fleet of police cars slowly emerge from the distant reaches of a hedge-lined road, bringing with them a real sense of dread. But it’s the smallest running theme, insert shots of characters tapping their fingers, that builds on the series’ inherent sense of drama with a repeated, recognizable action. If games have a way of showing us how we’re different, maybe the answer is to emphasize the ways we aren’t.

. . .

‘Black Earth Rising’ Is A Fascinating, If Clunky, Take On The Rwandan Genocide

John Powers, Fresh Air, January 30, 2019

April will mark the 25th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, a 100-day period in which world leaders stood idly by as more than 800,000 people — Tutsi minorities and moderate Hutus — were murdered by the majority Hutus, who had been whipped into a homicidal frenzy by their leaders.

The fallout from this killing spree is the subject of a clunky but fascinating BBC drama, Black Earth Rising, just out on Netflix. It was made by Hugo Blick, whose award-winning 2014 series The Honourable Woman used a deliriously serpentine plot to explore the Israeli-Palestinian conundrum.

Blick’s up to the same tricks in this new eight-part series, which offers us the gaudy goodies of a thriller — murders, chases and shocking revelations — in order to interest us in a tragedy whose aftershocks are still rocking Africa today.

Rising British star Michaela Coel plays the role of Kate Ashby, a 30-ish Rwandan who, as a little girl, was rescued from the 1994 genocide by human rights lawyer Eve Ashby — that’s Harriet Walter — who adopted her and raised her in London.

Eve and her American boss Michael Ennis (played by John Goodman) are dedicated to prosecuting those who turned Central Africa into a killing field. All of which is fine until Eve goes after a Tutsi general who, after helping end the genocide, went on to commit war crimes in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo. Kate is outraged. How can her own mom go after a man who saved Tutsis like herself from slaughter?

This tricky question gets even trickier once Kate finds herself working with Michael on a second case, this time defending a Rwandan government minister from a war crimes charge brought by the French. As the two cases cross-pollinate, Black Earth Rising races from London mansions to Congolese mining camps, from Parisian police stations to the presidential offices in the Rwandan capital of Kigali. Meanwhile, Kate — whose childhood trauma keeps her inner life churning — burns with a righteous anger that blinds her to the past’s full complexity.

Now, Black Earth Rising is decidedly not one of those current-events potboilers like Bodyguard or Homeland. It cares less about ratcheting things up than reminding us that history is vast, messy and ever-changing. Kate’s exploration of her past helps us understand the Rwanda genocide and its violent aftermath. We get details of how Belgian and French policies helped fuel the killing, and how colonialism still works today. We see how the Tutsi leaders who currently run Rwanda have created an orderly but dictatorial state. And more abstractly, we see how hard it is to define justice in a world where onetime heroes start doing bad things and fate transforms villains into victims.

Of course, it would take a lifetime to capture the complexity of all these things, and Black Earth Rising is only an eight-hour TV series. Although Blick tries hard to do justice to his subject, his ambition has a cost: The dramatic side of the series can be wobbly. Some of the dialogue is thuddingly expository, some of the plot twists feel mechanical, some of the symbolism is overbearing. And our heroine, Kate, is less a three-dimensional character than a walking emblem of Central African trauma.

Yet Coel plays Kate with such incandescent intensity that she keeps us riveted anyway. In fact, the whole series is superbly acted. There’s a winningly ambiguous turn by Lucian Msamati as the confidant of Rwanda’s president and a brilliant one by Goodman who, in Michael, aces a dream role — he gets to play smart, witty, soulful and, heck, even sexy.

In the show’s opening credits, we hear Leonard Cohen performing his song “You Want It Darker” in his incomparable hound-of-hell growl. Yet Black Earth Rising is actually about seeking the light. As Kate learns the buried truth about the past — her own and her home country’s — she begins to escape its clutches, transforming herself from an innocent victimized by history into a wised-up woman who’s trying to make it.

. . .

By Ericka N. Goodman-Hughey, ESPN W, Jan 25, 2019

Editor’s note: espnW celebrates the “Game Changers,” the empowering women who are breaking boundaries in sports and culture.

Michaela Coel sounded a bit muffled and slightly strained when she first popped onto the call. Promoting Netflix’s “Black Earth Rising,” which starts streaming on Friday, is part of the job. She is taking back-to-back phone interviews — fielding questions about the ethos of her character on the show, Kate Ashby. (“Black Earth Rising” initially aired on British television in late 2018.)

Life is a series of scripts for most actors. Coel, 31, has unapologetically decided to draft and control her narrative. “If I come onto any project — any film, any television program — I use my voice. I’m loud. I’m outspoken about the change I want to see.”

Kate is a legal investigator and survivor of the 1994 Rwandan genocide who was adopted by Eve Ashby (Harriet Walter), a British international criminal lawyer. The storyline references the Rwandan Civil War, also known as the genocide against the Tutsi people, which resulted in an estimated 500,000 to 1 million deaths. The eight-part fictional thriller, which also stars John Goodman as American lawyer Michael Ennis, is about the modern-day consequences of said genocide.

“We are all constantly figuring out our identities, each of us has many. We are constantly evolving, or at least we should be,” Coel said.

Kate is grappling with redefining herself and pursuing truth. Coel, who is of Ghanaian descent and was raised in the United Kingdom, is doing the same. She’s figuring out her next steps.

Coel catapulted into the spotlight in 2015, when “Chewing Gum” premiered (the show ended in 2017). Coel created, wrote and starred in the scripted TV comedy series as the protagonist, Tracey Gordon, a Beyoncé-obsessed 24-year-old Londoner who was continually battling the stronghold of religious-based guilt. Tracey was often awkward, unsure of her body as well as her purpose.

While discussing the show, Coel’s voice picked up in pitch, as if she’d shaken the exhaustion off her vocal cords. The conversation veered into her being sexually assaulted by strangers while working on scripts for “Chewing Gum.”

In August 2018, during her MacTaggart Lecture at the annual Edinburgh International Television Festival — where Coel was the youngest person and first black woman to present the lecture in its 43-year history — she publicly discussed her assault.

Coel said she had discussed the assault with the production staff of “Chewing Staff” years ago, right after it happened.

She noted during her lecture that their response was “teetering back and forth between the line of knowing what normal human empathy is and not knowing what empathy is at all. When there are police involved, and footage of people carrying your sleeping writer into dangerous places, when cuts are found, when there’s blood … what is your job?”

During the lecture, she also described being harassed by an unnamed television executive at an awards show after-party, who told her: “Do you know how much I want to f— you right now?”

There was some support in the aftermath of her lecture, like when Ian Katz, the director of programming at Channel 4, which originally aired “Chewing Gum,” noted that Coel’s speech was a “wake-up call.” However, there were also critics, who wanted to quiet her. “Some people said it wasn’t the right time or place to tell my story,” Coel said. “But, what’s the right time?

“My thing is, why silence myself? I am speaking up for those that couldn’t do so. I have to use my voice and opportunities to give light to those victims that didn’t have the opportunity.”

Finding her voice, being a leader and speaking out when she feels like it shouldn’t be seen as a rebellion, according to Coel. “I can’t allow anyone to silence me,” Coel said. “Even if I’m the loudest person and everyone is bothered by it, I am going to speak up for women, men and all non-binary people who have been assaulted.”

Coel’s current hairstyle was also seen as a rebellious act. “I cut my hair short several times, but I just wanted to shave it off. It felt right,” she said.

Coel had grown tired of being beholden to braids, pressed hair, weaves and wigs — at least exclusively. Her shaved head suited her and wearing it so closely cropped saved on grooming time. It was freeing.

“Who’s to say I can’t be me, can’t wear my hair as I please?” she said.

“It’s not me just being rebellious, this is me being me.”

. . .

Looking Back at the Rwandan Genocide

Five Survivors in Canada share their stories

By Kristine Magill, The Walrus Magazine, the Walrus Foundation, Toronto, Jan. 22, 2019

On april 6, 1994, a plane carrying Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana was shot down. Some details about the attack remain a mystery, but many believe that it was carried out by Hutu extremists angry at Habyarimana’s ongoing willingness to implement the 1993 Arusha accords. The agreement, sponsored by the United Nations, was designed to broker peace between the government and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (rpf), a rebel army made up of Tutsi who had fled the country to escape persecution. Rwanda had fractured on ethnic lines while a Belgian colony, and those divisions were aggravated after the Hutu revolution in 1959, which triggered the country’s 1962 independence. In a nation controlled by the Hutu majority, the Tutsi minority—often derogatorily called inyenzi (cockroaches)—suffered discrimination and violence.

In the years when the peace treaty was being negotiated, Hutu extremists were readying a “final solution” against the Tutsi. A propaganda campaign of hate, disseminated via radio and newspaper, led Hutu to believe that a Tutsi conspiracy to attack and kill them was underway and that heinous crimes were being committed against Hutu women and children. This anti-Tutsi narrative was further propagated in schools and churches. A government-affiliated youth militia known as the Interahamwe—“those who attack together”—was being trained to carry out the ethnic cleansing. Habyarimana’s assassination was seen as a signal to let the killing begin.

Government troops and the Interahamwe set up roadblocks around the country, and the carnage spread from the capital, Kigali, to the countryside. In some churches where Tutsi had gathered seeking refuge, priests helped point out who to execute. Ordinary citizens joined the action, slaughtering their Tutsi neighbours and, in some cases of intermarriage, their own family members. Those who didn’t want to take part were often forced to do so, threatened with death. After ten Belgian peacekeepers were killed, the UN refused to send reinforcements, and member nations gradually removed their troops. The remaining peacekeeping force, led by Canadian general Roméo Dallaire, worked to protect as many people as they could while Interahamwe troops committed atrocities that included raping women, murdering babies, and burying people alive in mass graves. Machetes, a common farming tool, were turned into killing devices. On July 4, 1994, after eighty-nine days of slaughter, the rpf seized control of Kigali and began restoring order. By then, at least 800,000 Rwandans had been massacred.

When I started working on a project to interview survivors who had settled in Canada about the horrific events they experienced in Rwanda, my goal was to record their testimonies for future generations and to share the lessons conveyed by their accounts. These selections from five survivors—identified here by either first name or pseudonym to protect their privacy—highlight just how easily people can be manipulated into turning against one another and how differences can be used to divide a society and breed hatred. Just as political leaders, government officials, the army, and the police can become enemies driven and encouraged to kill, so can priests, teachers, friends, and neighbours.

Twenty-five years after the genocide, Rwanda is a starkly different place. Ethnic classifications are avoided. The country is focused on uniting Rwandans; reconciliation is a major theme. The following accounts show, however, that the scars are still very real. For the survivors, coping with the trauma and rebuilding their lives remains a struggle. Their stories have taught me about the resiliency of the human spirit, and they demonstrate why we must counter divisiveness in all its guises.

—Christine Magill

INNOCENT

I remember the night the president’s plane was shot down. I was at home with my family; I was only nine years old, and the mood was sombre. Different neighbours came by our house to talk. There was a strong feeling that this was not going to turn out right and a sense that everyone knew what would happen next.

That evening, my aunt came to our house. She wanted to take me with her to a place she felt was safer. I still didn’t know what was going on. I was old enough to know that people were worried, but I didn’t really understand the specifics of what was happening. Families that owned radios would have guests every evening to listen to the news together; it was our only source for news on what was happening in the country. Often when we were listening to the radio, I would hear words like inyenzi(cockroaches), Tutsi, and Hutu and songs that would praise some and undermine others.

I left with my aunt and her daughter—she was about three years old—not knowing where we were going; it was strange that we were going for a long walk so late at night. My aunt, her daughter, her maid, and I left on foot and walked on the main road, since there were no cars running that late at night. Very few people even owned cars in our community, and those who had vehicles did not want to use them to escape, as they would be too easily noticed. It was a very dark night, and being in a rural area, there were no streetlights, so it was possible to move without being seen.

The journey with my aunt was around eight kilometres; we walked until we arrived at Lake Mugesera. She had a friend who lived there and had a boat, and my aunt was positive we could get assistance in crossing the lake. However, when we arrived, the family—which was Hutu—had already left. We spent the night in their backyard. I was thinking about my family and wondering how my sister and my brothers were doing and where they were. I learned later that four of my brothers and my only sister were killed, as were my parents.

Early in the morning, when the sun began to rise, we went to hide ourselves in a patch of nearby sorghum bushes. After we had been hiding for many hours, people began to arrive in the area and search for Tutsi to kill. One man spotted us in the bushes and let out a shout. The baby in my aunt’s arms started to cry. I jumped up and ran to a nearby water dike that was covered by bushes and hid there.

The man that had spotted us called for the others to join him. My aunt’s maid was Hutu; she was recognized by these people and taken by them. My aunt and her daughter were both slaughtered by the men. I could hear the sounds of them being killed from where I was hiding. After the men finished the killing, they came looking for me. They wandered the area but couldn’t seem to find me or see me in the dike where I was hidden. That’s how I survived.

I stayed there for a long time, probably even longer than I had to, before I climbed out to see what was going on around me.

COCO

My mom woke my sister and me at 7 a.m., telling us that the president had been killed. I was eleven years old. I didn’t really understand the significance of what she was telling us and thought it was nothing. However, she insisted that it was really important and that we needed to get up immediately.

Once we were dressed, my parents tried their best to explain what was going on. My dad insisted that we must eat breakfast before going anywhere. His biggest concern was that we would suffer from hunger. He gave each of us money, so that no matter what happened to the others, we would each have a way to get food and water.

My mom wanted to divide us up so there would be a better chance of someone in our family surviving. I went with one brother and one sister to an aunt who lived a twenty-five-minute walk away. She had moved to the city recently and wasn’t well known in the neighbourhood, so my mom thought we would be safer there. My six-year-old brother stayed with my mom, and another brother escaped and hid with a Hutu family. My eldest brother had been away at school but was home for Easter holidays. He survived by hiding elsewhere and also because many people did not recognize him and thought he was Hutu.

Before we left, I asked my mom if we would come back that night. She said maybe but that we needed to just go and see what would happen. My dad did not want to leave, he was feeling ill, and despite our pleas for him to come with us, he refused. My mom insisted on staying with him. I still did not really understand what was going on.

While growing up, it was hard for us to know about the terms Hutu and Tutsi. Our mom and dad wanted to shelter us from the ethnic tensions that existed in the country. They would tell us that if we were asked at school, we were Tutsi, but they didn’t explain what it meant. Sometimes in school we were required to stand at different times based on our designated ethnicity. Once, we asked our parents about it, and they explained that the terms were based on the number of cows or the size of a person’s nose. Still, we didn’t really understand what this meant. We had neighbours who were Hutu, and sometimes they would come over to our parties. Our friends at school were both Tutsi and Hutu, and our housemaid was Hutu.

My first experience with discrimination involved one of our neighbours who was Hutu. He didn’t want us to pass by his house to get to the main street and told us we had to find an alternate route. We asked him why, and he tried to intimidate us and said he didn’t want Tutsi near his house. My daddy was such a quiet, kind man—he didn’t want to cause any trouble—so he told us that anything someone asked of us, to just do it. He said that sometimes people are just rude and that we should just pass in a different way.

After leaving our home for our aunt’s, our location did not remain a secret for long. Our housekeeper told our neighbours where we had been sent. That evening, one of our neighbours came to my aunt’s house to tell us that he had killed my father and that we would be next. My daddy had been killed only hours after we left that morning. In the early stages of the genocide, the first priority was to kill the men and then kill the rest of the family later.

Despite these threats, we remained with my aunt. She was a member of the Presbyterian church, and she lived inside the church compound, which provided a greater level of protection. The pastor, who was a Hutu, tried to protect and hide those on the compound. We were moved to different rooms to keep us safe. Once, the killers came and found the room we were hiding in but were unable to get the door open. They told us that we must come out on the count of three or they would throw a grenade inside and kill us all. We knew that if we came out we would be killed by machete. My aunt told us not to be scared, as it would be better to be killed by a grenade than a machete.

Despite the efforts of the pastor, it eventually became too difficult to continue to protect us. The killers started to threaten his life, saying that if he continued to hide Tutsi, he would die. He warned us, coming to tell my aunt that he had received a letter from the killers stating that they were coming the next day and that nothing would stop them. My aunt decided that since my brother and I looked Hutu, we should leave and try to hide somewhere else.

I reached my uncle’s house with my brother and my cousin. My uncle, his wife, and their three youngest children were still alive. Their other three children had been away at school when the violence had broken out, so they did not know if those children were still alive.

My aunt stayed behind with four of her sons. Just after we left, they came and killed her. She was holding her youngest son in her arms as she was slaughtered. My sister, who was still at the compound, saw this happen. One of the Hutus among the killers knew my father and recognized my sister. He said that our father was a good man and offered to take her and help hide her. He told the others that she was a Hutu and had ended up there by mistake. She later escaped and joined us at my uncle’s house.

During the five days we spent at my uncle’s house, the killers would come and threaten us. My mom was still alive and had found out our location, so she would come and visit us in the evenings. She had my youngest brother, the six-year-old, still with her. When she visited, we would beg and cry to go with her, and she would explain to us that we couldn’t. She was hiding in the house of someone who used to work with my dad, but she was not allowed to bring anyone else with her because the family was scared of being discovered hiding Tutsi.

After the fifth day, the killers came at night and took my uncle and his wife. They told us that they were coming back to get us. We fled, taking my three young cousins with us, and tried to go to the place where my mom was in hiding. My mom was distraught; first her husband had been killed, and then her sister, and now her brother was dead as well. Every place she thought to be safe turned out not to be. She said that the killers should be called so that her children would not suffer any longer and we could at least all die together.

We were lucky to find out that my oldest brother, the one who had been away at school, was in the city and was still alive. He came to see our mother and found us there. He was twenty-two. He tried to find a way to hide us. Our house at that point was still intact and still had our stuff in it, so there was a potential that we could try and sell things and then pay someone to assist us. It is important to remember that, during the genocide, some of the Hutus in Rwanda tried to help the Tutsi. However, they were also traumatized and threatened. Many would eventually tell Tutsi to leave because their own life was being threatened for hiding us.

Eventually, my brother found a family that was willing to help us. The wife was a Tutsi and the husband a Hutu, and they had plans to escape to Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. When we got to Zaire, we met a Tutsi woman who had escaped and was helping survivors at the border. She must have known my mother, because when she saw me, she said my mother’s name, saying that I looked like her. I told her that yes, that was my mother, and she let us stay with her.

ANNICK

I grew up in a Christian family, the ninth born of ten kids, with four brothers and five sisters. My dad was a pastor with the Anglican church, and my mom stayed home and cared for us.

We lived in an area known as Nyamata, where there was a large population of Tutsi. My dad used to teach history, so between his knowledge and his own experiences while growing up, he knew a lot about Rwanda. From my father, I learned that Tutsi had been forced to move to the area and that this had been done intentionally to make it harder for them to survive.

When the genocide occurred, I was twelve years old. The night of the plane crash, I was at my cousin’s house for a sleepover. When I got home in the morning, my house was full of people—all my aunts, uncles, and their kids. Most Rwandans at this time had big families with anywhere from seven to twelve kids. I went to my mom to ask her what was going on and why all the people were there. She took me into the bedroom and told me to put on extra clothes in layers. When I asked her why, she replied that we had to flee from the house, that we were going to go to the church. That same day, my three brothers and my male cousins left the house to see what was going on in the neighbourhood. When my brothers arrived home, they told my dad that he needed to leave the house because he was on the list of people to be killed that day. My dad left to go hide with another Tutsi friend.

That night, we all slept outside in the bushes. My father joined us in our hiding place. I could hear people screaming on the other hills. The next morning, we returned to the house, leaving my father behind, hidden in the bushes. My dad said it was not safe for all of us to stay there and that the best plan was to try and go to the church or the commune office. My father was in his late fifties. He told my mom’s brother that he could not afford to run and be hunted by the people he knew. I think he wanted to maintain his dignity and did not want to spend the last bit of his life fleeing from those he used to employ and help provide for.

That was the last time I saw my dad. The image is imprinted in my mind. We had been hiding on a hill, and as we walked down, I looked back behind me, and I could see him standing there at the top.

We travelled down from the hills on our way toward the Nyamata church. We passed people who had been hacked by a machete and were not dead yet. Some were running and bleeding everywhere. When we got to Nyamata, we could see the bodies of people lying in the streets. We began running toward the church, and the closer we got, the more bodies there seemed to be. People were screaming and shouting and babies were crying. My mom told us to grab the hand of another person so that we would be in groups of two. The Interahamwe were getting close and started shooting at everyone who was running. My sister and I were holding hands, and we lost sight of the rest of our family. We spotted a house and ran inside.

Within fifteen minutes, the Interahamwe burst in and demanded that everyone come out of hiding and gather in the living room. I can’t explain how I felt at that moment. I was terrified, standing there in front of men holding machetes covered in blood. You know you are going to be killed. They are killing those around you, and you know you are next. Most of the people in the house were kids my age or my sister’s [sixteen]. One of the soldiers decided that they shouldn’t bother killing us at that moment.

Every time people ask me how I survived, I say it was a miracle. Every day was the day you were going to die. If you made it to the next day, it was only because of a miracle. There in the house was the first time I faced death up close. I could see the faces of those that didn’t look human. They were ugly, angry, and hungry to kill you.

We were sent to the area where others were gathered and being guarded by the Interahamwe. We saw my uncle and sat with him and some of his children. He told us our mom was there but that it would be impossible to reach her—by this point, so many people had been gathered in the area that it looked like a crowd in a stadium.

We had been there for less than twenty minutes when we saw buses pull up and park. After that, everything happened very, very quickly. Interahamwe piled out of the buses wielding machetes and other weapons and began attacking everyone that was gathered.

We stood up and started running.

Someone ran between my sister and me, forcing us apart. I could see her running; she yelled at me to keep going. After a few minutes, I lost sight of her in the crowd.

My dad’s words came back to me—he had told us to go to the church—so I kept running.

When I got to the church gate, someone grabbed me. It was a woman named Grace, the wife of one of my dad’s friends. She seized my hand and told me that I couldn’t enter the church. I tried to resist her, but she wouldn’t relent. I wanted to go in, as I was certain that was where I would find my family. She continued to tell me I couldn’t and asked that I follow her.

Grace’s four daughters were with her, and she took us to hide in a banana plantation. We stayed there for the night. I was restless and wanted to go back and search for my family. Grace kept reassuring me; she told me not to worry and that we would meet up with my family later. I think at this point in time, everyone still thought the events that were happening were temporary—that things would calm back down and the killings and violence would come to an end.

The next day, we continued to hide at the plantation. The Interahamwe were killing people in the area, and more Tutsi were arriving to hide. Grace’s daughters, who were older than me, would take me a short distance away to talk and distract me, while Grace asked the newcomers questions. She tried to find out where they were coming from and what was happening at the church. I wanted to know what was going on, but she did her best to shield me from any news.

Near Nyamata, there is a bridge that runs over the Nyabarongo River where they were throwing dead bodies as well as people who were still alive into the river. Near the banks of the river, there are very high grasses and a swampy area where no one goes because it is so dirty. We left the plantation and went to hide in these grasses. I think most of the Tutsi who survived the attacks in the Nyamata region did so by hiding there.

I eventually lost track of the days and what was happening. We would sleep at one place for two or three days and then move to the next spot. I no longer knew where we were, just that we were living in the bushes and had nothing to eat. Throughout this time, I continued to ask Grace, “Where is my family? When are we going to go back?”

She just kept telling me, “Don’t worry, we will go back,” or, “Everyone is coming, we are going to meet them,” in an effort to reassure me and keep me calm.

Despite frequently moving, we were still in the area near the river and eventually reached a point where it was necessary to cross the river to get to the province, Gitarama, on the other side. Grace thought it would be safer there and that the killings may not have started yet.

The Interahamwe were waiting in the area for people to come and try to cross the river so they could kill them. There were also Hutu with small boats offering transportation for those who could pay. At the time, we thought those Hutu were saving people’s lives. We found out later that they were really just using it as an opportunity to make money, while knowing that those they transported might just be killed on the other side.

Grace paid money for one of these boats for us to cross the river, thinking we would be safer. As we crossed the river, I remember watching people commit suicide by jumping in the water. They were intentionally drowning themselves so that they would not be killed by machete. One woman first threw each of her kids in the river and then jumped in herself to die.

Somehow, we survived the trip across the water and away from the river. We travelled to a nearby church and slept there for a few days, until people arrived to begin killing once again.

MARIE

My dad was a good man. He never wanted us to know if we were Tutsi or Hutu. He didn’t like that the terms divided people. He would say, “Just know that you are Rwandese, that’s it.” The rest of society did not think like that, though. Neighbours and other people around you would always know your ethnic identity. At the beginning of a school year, they would ask us to line up by ethnicity: “Tutsi should be here. Hutu should be over here.”

My father would always tell us, “You have to love people whether they’re rich, poor, Hutu, or Tutsi, or another ethnicity. It doesn’t matter. You can dislike the things others do, but you still have to love people and respect them.” Those lessons really helped me. I had such trust in my dad that I would always keep those messages in mind and think about what he would want me to do in any given situation. Some days, though, it was very hard to live up to his lessons, because how can you love somebody who doesn’t love you? Who hates you and wants to get rid of you? But I would still try.

In 1994, I was thirteen years old and was in grade seven, my last year of primary school. When the genocide began, it wasn’t a surprise to anyone: the country was controlled by Hutu extremists and preparations were out in the open. Militias were being trained. It was clear that the government was organizing something.

After the plane crash, it took a few days before anything happened in our area. Everything was shut down, and no one was able to go to work. We stayed in our home, waiting to see what was going to happen. A few days later, my cousin, who lived up the street, was killed. We knew then that we would be next.

That evening, we went to our neighbour’s home. He was Hutu, and we thought that if we hid there, we would be safe. He had a big tree with branches that extended across to our side, so we climbed onto the wall that surrounded our home and then onto the tree. Nobody knew how we escaped. The cars were still parked in front of our house, all the doors were locked from the inside, and it looked like we were still at home.

When the killers arrived the next day, they brought a machine to force open the doors. When they got inside and couldn’t find us, they became extremely angry. Then some of them came over to the house where we were hiding. The neighbour had barricaded us in a room without a window so that we wouldn’t be spotted. The men smashed the windows in his home and looked inside, but they couldn’t see anybody. Next, they tried to open the door to the room where we were hidden, but for some reason, it wouldn’t open. God must have been protecting us. They decided they would come back later and remove the door.

That night, the neighbour dug a hole into the wall of the room for us to climb out of. He had to do it very quietly so that no one would hear what was going on. Sometime around 2 a.m., we were finally able to climb out of the room.

We were close to the hospital, so one of my brothers told us he would go ahead to see if it was safe and that if we heard him screaming, we would know not to come that way. We tried to argue with him; we wanted to stay together. But he insisted and went on ahead of us. After a minute, we could hear his cries as he was killed.

Out of fear, we kept moving. We tried several other places, including a convent and a church, but neither one was accessible. Finally, we went to the high school and found people gathered there. They had opened the gates to the school, and the buildings were full of Tutsi. We spent what remained of the night there. Around 10 a.m., the Interahamwe and local killers arrived. I was with my younger sister when the killing began, and we became separated from the rest of the family. I found out later that one of my other sisters also survived as one of the Interahamwe soldiers recognized her. She was able to bribe him by giving him her jewellery and her glasses.

The killing in the school was done exclusively by the men. There were women as well, but they held the responsibility of walking through the bodies of the victims to retrieve any jewellery, money, extra clothing, or valuable items that had been brought by those fleeing. They ordered everyone to lie down on the floor. Then they began killing. I am haunted by the sounds of those dying and by the noises the weapons made as they hacked people to death and beat us with clubs. For some reason, despite being chopped and cut with machetes, my sister and I didn’t die. We were very injured, but we were still alive.

Several of the women I used to see at the market came, and they were looking through the bodies for items when they recognized me. Despite my disfiguring injuries, the women recognized me. I was still conscious, and I could hear what they were saying; “Oh! That’s her! She used to be so kind to us. Why would they kill her?” They realized that I was still alive, and they quickly grabbed me and moved me to the side. They told me, “We’re so sorry,” and then among themselves they began discussing what they should do. “We have to do something about her! If we don’t do something, she will be gone completely.” The killers had plans to return the next day to burn all the bodies. There were so many corpses that they didn’t want the work of trying to move and bury them. It would also kill anyone who was still alive.

I knew my sister was also still alive, as she had been lying next to me. I told the women, “She is the only one that I have alive. You have to do something about her too. If you don’t, let us die together because what’s the point of surviving without her?” They replied, “Your sister didn’t treat us the same way you treated us.” They said they weren’t willing to save her.

“Leave us alone then,” I said. My sister couldn’t stand the women, as they were not very nice people; she had never made an effort to be nice to them. Despite how they acted, I had always tried to show them kindness and respect. I wanted to obey my dad, to do the best to follow what he had told me. In return, they had also treated me better. I told the women again, “Okay. Just leave us alone.”

In the end, they decided to help both of us. They said, “Your sister probably won’t last long anyways.” They were not able to take us anywhere that night, but they moved us to a different area and returned to get us early the next morning before the killers arrived to dispose of the bodies.

For a short amount of time, we were cared for by these same women. Soon after rescuing us, they helped us move to the home of two of our Hutu friends. By the end of the week, the rpf was advancing and was close to reaching the area; we could hear the guns and fighting going on nearby. There were discussions among the killers about finishing off any Tutsi that were still alive so that there wouldn’t be any survivors or witnesses. We were certain the killers were going to come before the rpfreached us. However, for some reason—maybe how quick the rpfapproach was—they ended up leaving us inside the home and fleeing the area.

BERTIN

My passion as a child was soccer. I had a couple of cousins in my neighbourhood close by, so we would get together to play: my brothers, cousins, and friends. My family was not poor, but we also were not rich. We were able to afford a normal soccer ball, but many of our friends could not, and we wanted to use the same kind of ball they used, the kind you make yourself. So I made soccer balls using plastics and rope. As a young child, the experience of making something of your own was the best. Not only would you end up feeling happy that you had made it but you would also feel proud and your friends would admire it.

When I was growing up, my parents didn’t talk to us at all about the differences or the hate between ethnicities in Rwanda. They avoided the topic, and we weren’t permitted to discuss it. We would hear comments about it from other people who were speaking about what was going on, but because we didn’t have any background knowledge, we didn’t understand what was being said. If we were playing together every day, to me we were the same. If I was playing with my neighbour who was from the other ethnicity, he was my friend. If my teacher asked him to stand up, I would stand up as well. I couldn’t really make out a difference because I couldn’t understand it. What was hard was the way people looked at you if you were Tutsi, even children, as if you were a stranger in your own country. Others would look at you like you were an animal, and you couldn’t help but wonder what you had done to be viewed that way.

After high school, it wasn’t possible to go to university or continue with any type of schooling. Finding work could be really difficult, as there were not enough jobs available for Tutsi. Hutus were given preference for many positions, and finding work was also very much based on who you knew, not your qualifications. I was lucky and managed to get hired by a friend of my parents for a job only a short bus ride from home. In high school, I had received training for working with electricity and was hired as an electrician for the hydroelectricity company. I worked there for three years, until the war started in 1990.

Two weeks after the rpf invaded Rwanda, I was arrested and thrown in jail. The specific accusation was that I was working with the rpf and that, because I worked in hydroelectricity, I had plans to shut off the electricity and lights for the entire town. I was in disbelief. I had no access to the department to do this. At first, I thought it was a joke.

I stayed in jail for six months. When I was finally released, I discovered that there were no more buses, no more taxis—there was nothing, and everything was quiet. When I tried to return to my old job, I found out I was fired. They told me the official reason was that I had disappeared from the office without a reasonable explanation. I decided I needed to start a new life. There was no way I could continue to depend on my mom, but at the same time, there was nothing I could really do where I was. I needed to leave. I started looking for a way to leave the country. That is how I ended up coming to Canada.

While i was in jail, I had registered with the International Committee of the Red Cross as a political detainee. I came to Canada as a refugee. I arrived in Montreal during June 1993. I had culture shock when I first arrived. You leave the airport and find yourself in a big city. In Rwanda, you are familiar with everyone and greet one another on the street. Here, I would see everyone walking around without talking to each other. It was a huge shock. But it was summer, the weather was perfect, and the city was beautiful. People were outside, laughing, enjoying life. If anything, I found the temperature too hot, as we do not have much humidity in Rwanda. Even with the culture shock, I found that, compared to the life I had left behind, everything was a piece of cake.

Then winter came. People had tried to warn me, but it was a huge shock. I couldn’t believe how cold it was. I had no frame of reference for this type of weather, and even if someone had tried to explain the temperature, I wouldn’t have understood. I had been hearing about it on the news, in school, but I really didn’t know how to prepare. My first winter, I got burned from the cold. I had to go to the doctor. He explained that I had frostbite and asked how long I had been in the country. I told him six months, and he explained that I needed to cover myself up, that it was too cold for what I was wearing.

When I came to Canada, the nation was in a recession; I remember it very well. The prime minister until the month of my arrival was Brian Mulroney, and he was followed by Kim Campbell. I liked following the news on TV, and they kept talking about this term recession. It was the first time I had heard of the concept, and I had to ask someone to explain it to me. They told me that there were no jobs. I discovered this myself when I tried to find work.

I was unable to find any work until January 1994. I finally got a job working for Zellers in its warehouse. It was very hard physical work and not like anything I had done before. However, it was what I needed to do to survive, so I did it. It was such a change being alone now and not with my family; everything was now by myself.

Iwas twenty-six when the genocide began. I had been preparing to go to British Columbia—I heard there were more jobs available. Everything had been paid for and planned. Within a week or two, all the phones were cut off in Rwanda, and I lost all communication with my family. I found myself faced with a big decision. Do I go to BC or do I stay here in Montreal? I realized that even if I stayed in Montreal, there was nothing I could do. There was no communication, and it didn’t matter where I was—it wouldn’t change that situation.

I ended up in Prince George, BC, and started working for a tree-planting company. When you are working in tree planting, they give you a piece of field to work on, a square piece of land that they call a “block.” What was funny was that because of the language barrier and difference in accents I kept hearing the word black. So people would continuously be saying “block,” and I heard “black.” I kept getting so mad, because I thought everyone was talking about me behind my back, and I didn’t know what they were saying. I would hear phrases like “this black here” and wonder, “What are they saying about me? What did I do to them? I’m trying to be as straight as possible. I don’t want to create any problems, yet they keep talking about me. What did I do?” It took me from April until July to finally understand what was happening. I saw the word written on a piece of paper; it was a block.

As time passed, I continued to have no news about my family. Before this, I had always been in communication with my mom, brothers, and sisters. We had no email back then, but we would send each other letters. I still have them today. Unfortunately, before the genocide, my family believed that everything was becoming better in Rwanda because of the arrival of the UN peacekeepers. When you have been in a situation for a long time, it seems like it is normal, and you get used to it. You don’t see the danger around you; your eyes are closed because you are so used to it.

After the tree-planting season finished, I returned to Montreal. Two days later—it was October by then—I received a call from my sister-in-law. She said hello and then told me she didn’t have much time and asked if I could just listen.

“Your brother is still alive. Me and my two kids. That’s it.” She then began listing names from my family, then my best friend, then everyone I knew.

“All those people?” I asked.

“Yes. They are dead.”

That was a turning point in my life. Yes, I had lived through challenges, been to jail, and had a difficult life. But what was I doing here? Why am I still alive and my family is dead? I was questioning myself, questioning everything. I spent two days in bed, just sick—sick from rage, anger, everything.

Life changed for me. The way I saw life, the way I saw people, the way I now understood how things worked. I became another person—in terms of sensitivity, in terms of my emotions. You ask yourself, “Why am I alive?” You suffer from survivor’s guilt. I would think back to my journey and how I ended up in Canada and wonder, “Why me?”

Adapted with permission from The Hope That Remains: Canadian Survivors of the Rwandan Genocide. Copyright © 2019 Véhicule Press.