Issue of the Week: Disease

Prenatal alcohol abuse PSA (c) 1992-2019 Planet Earth Foundation

“We have to scream about this problem to the world.”

-Dr. Svetlana Popova, senior scientist, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health’s Institute for Mental Health Policy Research in Toronto

In 1992, and thereafter, a primary focus of our work was to enhance publicly funded programs proven to work efficiently to further the health and eliminate the damage to infants, children and their mothers. The focus on maternal child heath was well understood and proven to work. It was guided in the main, in our experience, by who it should be guided by–women of diverese backgrounds who were strong leaders in getting the job done.

What job? Making sure the common sense and science-based basics were provided to children and mothers from prenatal through the first years of life upon which the rest of development so depends.

So you start at the start. Prenatal care for those women who decided to carry their pregnances to term.

For those who chose this, one of the first and most critical choices was to forgo all substance use during pregnancy, or risk condemning their children after birth to enormous damage.

And this started with the most widely used legal drug–alcohol.

So common sense women, feminist women, liberal women, conservative women–in the main, created and required cultural consensus to follow science and common sense to create healthy mothers and healthy babies. We worked with these programs, from maternal and child health departments to Women, Infants and Children (WIC) programs around the US.

We created the first large scale prenatal care public service advertising campaign based on these principles to among other things, make clear to women that the risks in drinking while pregnent at all, ranged from damaging to lethal to the infants they were choosing to bring into the world and the children they were choosing to raise.

Our campaigns worked. All such campaigns worked as long as they were of the highest quality and the highest sensitivity for diverse groups. Its called good advertising, in this case, in the public interest.

But it has to continue, and be ever-present, the way the advertising industry is in selling consumer goods.

And it needs the resources to do not only this, but to counter the ad campaigns of the very interests which depend on say, alcohol abuse.

Not an easy task. We started the first part successfully, but the second part would have required a revolutionary moment of enlightened self-interest. The National Academy of Sciences asked us to try. The story of what unfolded, and lessons learned, is to come. Let’s just say for now that if you want to do good and not let money corrupt your values, you have to be willing to say no to millions, and to lose everything to do the right thing.

For now we start with prenatal care to prevent alcohol consumption by pregnant women, or for the sake of their own bodies in general and when they aren’t yet sure if they’ll have children or what they’ll do if they become pregnant. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the US suggesting the latter reminded of where we are as a culture. But more on that later.

For years, we conducted campaigns that were always present and convincing. It was a cultural given that you didn’t drink, smoke or drug while pregnant, just as it was a cultural norm that breastfeeding was best for mother and child. These messages never stopped coming–the necessary repetion of good advertising.

But then the messages didn’t keep coming on the same level, and the counter messages of the culture in an increasingly downward spiral, enhnaced by the constant marketing of the merchants of substance abuse, took their toll.

This is going to be a longer conversation, but let’s start here. If a gifted feminist doctor is compelled to explain on the pages of The New York Times that not drinking during pregnancy is not sexism (yes, you’re scratching your head understandably), then you will read the measure of how “do your own thing” is a strain of culture that has invaded everytihng and been elevated (in only a few places to be sure) to ideology. The thing is, when its used as ideology on the left and right, what you are really looking at is one excuse or another for just doing what ever you feel like and vacuously trying to elevate it to a system of values. The whole culture suffers from this dumbed-down narcissism, hence the times we live in.

But it’s useful here to start with an intelligent and scientifially-based effort to bring people to their senses. The Op-Ed yesterday in the New York Times refered to above notes, and leads to re-examing, one of the most important reports released in a long time, and paid scant attention to, one year ago exactly.

We may well have 10% of our children being seriously damaged by women drinking during pregnancy. Do you know how many children that is? And what this can do to them, and the rest of us, and the next generations, for the rest of their lives?

The numbers may be smaller–the median of the study is around 5%–but how does that work out? Besides, the very issues which led the researchers to different possibilities argue strongly for a higher figure than they’ve arrived at yet.

So consider this part one of a far larger topic.

Not that millions of damaged children every year isn’t a large enough topic.

So today, we start with the new Op-Ed in the New York Times, and conclude with the story in the Times exctly one year ago on the pandemic of devastatation caused by the prenatal use of alcohol. A very powerful drug as a reminder. Just happens to be legal and in the culture for a long time. Most people don’t drink or drink very little. And the answer is certainly not to revert to illegality. But there are solutions.

Drinking While Pregnant: An Inconvenient Truth

The Cycle, By Jen Gunter, Feb.5 .2019, The New York Times

Recommending that pregnant women not drink alcohol has been called old-fashioned and even patriarchal. So, as a feminist, my opinion may come as a surprise.

Pregnant women are given a long list of medical recommendations that can come across as patriarchal don’ts: Don’t eat raw fish. Don’t consume deli meats. Don’t do hot yoga! Don’t drink.

There’s scientific evidence that these activities can have negative impacts on the health of the fetus, but the one that seems to be the source of most debate is alcohol.

After all, the French do it, don’t they?

And many people born in the 1960s or earlier had mothers who drank. And we’re fine, right?

My mother had a fairly regular glass of rye and ginger ale when she was pregnant with me. And she smoked. And I graduated from medical school at the age of 23.

So my opinion, especially as someone who believes strongly in a woman’s right to make decisions about her own body, may come as a surprise: It’s medically best not to drink alcohol in pregnancy. Not even a little. The source of that viewpoint? My training and practice as an OB/GYN.

Some attribute this abstinence approach to the patriarchy: Clearly we doctors know that moderate alcohol is safe (we don’t!), and we just don’t trust women with that knowledge. According to this theory, we think a woman who hears that an occasional drink is O.K. will blithely go on a bender. (We don’t think that.)

Some also say that, in an effort to avoid frivolous lawsuits, doctors advise against alcohol while using a nudge-nudge-wink-wink to insinuate that a glass or two is fine.

But this isn’t about sexism (not this time) or dodging litigation. This is about facts. How women use those facts is, of course, their choice.

The truth is that fetal alcohol syndrome is far more common than people think, and we have no ability to say accurately what level of alcohol consumption is risk free.

There have been many twists and turns in how we, medically and societally, view drinking while pregnant.

There was a time when doctors recommended alcohol to pregnant women for relaxation and pain relief, or even prescribed it intravenously as a tocolytic — meaning it stopped premature labor. One doctor who trained me spoke of a 1960s prenatal ward full of intoxicated women “swearing like sailors.”

Things began to change in 1973, when fetal alcohol syndrome, or F.A.S., was formally recognized after a seminal article was published in The Lancet, a medical journal. F.A.S. is a constellation of findings that includes changes in growth, distinctive facial features and a negative impact on the developing brain. We now know that alcohol is a teratogen, meaning it can cause birth defects.

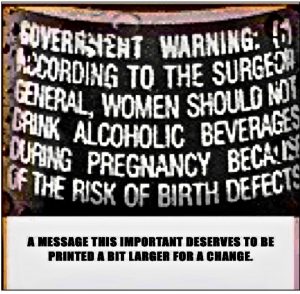

With that knowledge, the pendulum swung hard. In 1988, Congress passed the Alcoholic Beverage Labeling Act, which would add the well-known “women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects” label to alcoholic beverages for sale or distribution in the United States. (A warning about drinking and driving was also added.) Many people unfortunately took this as an opportunity to police pregnant women in public.

Then, over the last 10 years, women have become more vocal — and rightly so — about patriarchal messaging in medicine. Was no-drinking-while-pregnant just one more way to speak down to us and control our bodies?

No. But I can understand the confusion.

Part of the issue is that the science on alcohol and pregnancy is tricky: Giving pregnant women alcohol for medical testing is not likely to be accepted by ethics committees.

And what about all those pregnant Frenchwomen who drink (while also apparently shedding their baby weight with ease and bringing up perfect bébés)? It turns out they aren’t, really. One study in Europe that surveyed pregnant women and new mothers during two months showed that only 11.5 percent of women reported consuming alcoholonce they knew they were pregnant. Of these women, most (72 percent) had a single five-ounce glass of wine or less the entire pregnancy.

We now have new data in the United States telling us that rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (F.A.S.D.) are higher than we knew. In 2018, a paper on F.A.S.D. was published in the medical journal JAMA. Researchers trained in identifying the distinctive physical characteristics of F.A.S.D. evaluated over 3,000 children in four communities across the United States.

The findings were staggering. The way we are consuming alcohol in pregnancy is resulting in a conservative estimate of 1.1 to 5 percent of children — up to 1 in 20 — with F.A.S.D. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are more prevalent than autism.

And yet at least 10 percent of pregnant women still drink during pregnancy.

The best analogy for the risk associated with alcohol consumption in pregnancy is driving with your newborn unbuckled in the back seat. Maybe you’ll get into a car accident and maybe you won’t. And if you do, maybe it will be a fender bender or maybe it will be catastrophic.

Driving is also not the only factor at play, in the same way that differences in body chemistry can play a role in who develops F.A.S.D. There is also the ability of your newborn to withstand an impact, the weather, the number of cars and the state of mind of other drivers on the road.

While the chances of getting in a car accident while driving home from the hospital with your newborn are very small, most parents will recall how much they stressed over installing the car seat correctly. (I released a lot of pent-up rage in the hour it took me to get the car seats buckled the first time.)

And yet, even with such limited risk, I doubt a single pediatrician would say: “Sure, drive unbuckled just this once. It’s a celebration.”

Guidance to not drink while pregnant is not sexist. I’m all for smashing the patriarchy at each and every opportunity. And it’s true that medicine has been hopelessly patriarchal since, well, medicine started. But providing people with accurate information so they can make informed choices about their bodies is the antithesis of the patriarchy. It is power.

Dr. Jen Gunter is an obstetrician and gynecologist practicing in California. The Cycle, a column on women’s reproductive health, appears regularly in Styles.

. . .

Far More U.S. Children Than Previously Thought May Have Fetal Alcohol Disorders

By Pam Belluck, Feb.6. 2019, Health, The New York Times

More American children than previously thought may be suffering from neurological damage because their mothers drank alcohol during pregnancy, according to a new study.

The study, published Tuesday in the journal JAMA, estimates that fetal alcohol syndrome and other alcohol-related disorders among American children are at least as common as autism. The disorders can cause cognitive, behavioral and physical problems that hurt children’s development and learning ability.

The researchers evaluated about 3,000 children in schools in four communities across the United States and interviewed many of their mothers. Based on their findings, they estimated conservatively that fetal alcohol spectrum disorders affect 1.1 to 5 percent of children in the country, up to five times previous estimates. About 1.5 percent of children are currently diagnosed with autism.

“This is an equally common, or more common, disorder and one that’s completely preventable and one that we are missing,” said Christina Chambers, one of the study authors and a professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “If it truly is affecting a substantial proportion of the population, then we can do something about it. We can provide better services for those kids, and we can do a better job of preventing the disorders to begin with.”

The range of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (also called FASDs) can cause cognitive, behavioral and physical difficulties. The most severe is fetal alcohol syndrome, in which children have smaller-than-typical heads and bodies, as well as eyes unusually short in width, thin upper lips, and smoother-than-usual skin between the nose and mouth, Dr. Chambers said. A moderate form is partial fetal alcohol syndrome. Less severe is alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder, in which children have neurological but not physical characteristics and it is known that their mothers drank during pregnancy.

Dr. Chambers said the researchers were in the process of analyzing the mothers’ answers to questions to see if they can identify relationships between the timing and amount of drinking during pregnancy and the type and severity of children’s impairment.

It has been unclear how common these disorders are because the facial features are subtle, and some effects, like problems paying attention or recognizing the consequences of behavior, can apply to other diagnoses. Also, the degree and area of a child’s brain damage appears to vary depending on when and how much during pregnancy the mother drank, as well as genetics, so symptoms can vary, too.

Then there is the stigma that often makes mothers reluctant to acknowledge alcohol consumption.

“When you identify a kid with FASD, you’ve just identified a mom who drank during pregnancy and harmed her child,” said Susan Astley, director of the Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Diagnostic and Prevention Network at the University of Washington, who was not involved in the study.

While Dr. Astley, a longtime expert in the field, said she admired the researchers’ hard work, she said the reliability of the study’s numbers was hampered by several factors. For example, only 60 percent of eligible families in the schools allowed their children to be evaluated and more than a third of those children’s mothers declined to answer questions about drinking during pregnancy.

“If we could generate accurate estimates of FASD, we’d all benefit,” Dr. Astley said. “But the major limitations in the study design render the results, for the most part, uninterpretable.”

The authors of the study, which was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, acknowledged the study’s limitations and tried to partly compensate by providing a conservative estimate (of 1.1 percent to 5 percent) that is likely low and another estimate (of 3.1 percent to 9.9 percent) that is likely high. Dr. Chambers also said the results might not generalize across the country because although the four communities were diverse, they did not include a large, high-poverty urban area or certain rural or indigenous communities that struggle with high rates of alcoholism.

The locations, which are not named in the publication, include small-to-midsize cities in the Midwest and Rocky Mountains, a Southeast county and a Pacific Coast city the authors identified in interviews as San Diego. Participating first graders were given neurodevelopmental evaluations and most also had their facial features evaluated by dysmorphologists. About 62 percent of the first graders’ mothers were interviewed.

Of 2,962 children evaluated, the researchers identified 222 with a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Dr. Chambers said. All but two of them had not been previously diagnosed, although the authors said many parents had been aware their children had learning and behavioral difficulties.

“It’s kind of like the hidden problem,” said Dr. Howard Taras, a study author and professor at the University of California, San Diego, who is the physician for the San Diego Unified School District, which participated in the study. “If not in one classroom, certainly in another, there’s going to be one or two kids with these problems, but they’re not identified as such.”

Identifying children with alcohol-related impairments can help teachers and psychologists work with them more effectively, experts said.

Even if educational approaches might resemble those for other special needs children, the diagnosis tells teachers behavior problems are “not because this child is disobedient, it’s because of some neurological disorder,” said Dr. Svetlana Popova, a senior scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health’s Institute for Mental Health Policy Research in Toronto, who was a co-author of an editorial about the new study.

Dr. Astley said a diagnosis might inform medical treatment, as well, because some medications, like Ritalin, might work for inherited attention deficit disorder, but not attention deficit symptoms caused by alcohol.

Recently health authorities in the United States have sharpened warnings about alcohol in pregnancy. A 2015 American Academy of Pediatrics report said “no amount of alcohol intake should be considered safe” during any trimester. In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, noting that half of American pregnancies are unplanned, recommended that sexually active women who are not using birth control “not drink alcohol at all.”

To the astonishment of people working with alcohol-damaged children, the C.D.C. report unleashed a swirl of pushback from those who considered the advice insulting, shaming or over-the-top.

“People say, ‘Don’t be ridiculous, I went to a wine tasting and my kid came out fine,’” Dr. Taras said. “But the C.D.C. is saying, ‘We don’t know. Maybe you just won the lottery.’”

Experts say there is evidence that more drinking causes more damage, but much remains to be learned, and in some women even a small amount of alcohol can seriously affect a baby, Dr. Astley said. She added, “There’s probably no two women on the planet who drank the same amount on the same day of pregnancy. And alcohol doesn’t impact every fetus in the same way.”

Dr. Popova said she hoped the new study would make people pay attention.

“Alcohol can damage every system of the body,” she said. “We have to scream about this problem to the world.”

. . .