Issue of the Week: War, Population, Human Rights, Hunger, Disease, Economic Opportunity

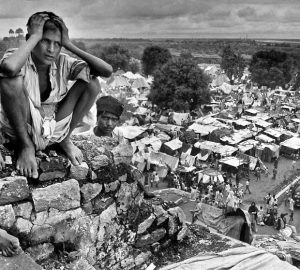

Partition of India and Pakistan, 1947, Maragaret Bourke-White

“That there hasn’t been a war between India and Pakistan involving nuclear weapons does not mean it cannot happen.”

–The Atlantic, February 27, 2019

As we’ve noted often, India will soon have the largest population in the world.

If it hadn’t been partitioned at independence from the British in 1947, there would be no Pakistan or Bangladesh and India would long ago have been by far the largest nation on earth.

Since partition, one of the most horrific and traumatic events in history, India and Pakistan have largely been at each other’s throats, with Bangladesh existing in no small part because of this.

(The photo above of the boy at the refugee camp in 1947 is one of many famous photos by the legendary photo-journalist Margaret Bourke-White. We highly recommend searching her incredible photos and life story.)

While the world has been focussed for a couple of days on the US-North Korea nuclear summit (and barely focused on this in the never-ending toxic blizzard of news in our times), the far more threatening possibility of nuclear war between India and Pakistan has been unfolding.

All the related historical, nationalist, religious, ideological and other issues are important to understand.

Most important are the usual underlying causes of instability.

India and Pakistan (and Bangladesh) have made progress in various ways and degrees in terms of the well being of their people. But not sustainable progress.

The World Food Programme reports that one quarter of all undernourished people on earth live in India.

And nearly half of the population of Pakistan is food insecure.

A couple of decades ago it was worse. But the measures of absolute poverty generally used are absurd in real life application, as we’ve pointed out before. And the genuine progress on related fronts is, as we noted above, unsustainable without enormous policy changes.

As always, we’ll return to these issues.

For now, we focus on the extraordinary danger in India and Pakistan, and the impact on the entire region and the world.

A favorite phrase lately–start at the start–pertains.

A year ago last August was the 70th anniversay of the partition.

We re-post below an excerpt and related article from our post then.

First we post an excellent and chilling article in The Atlantic today, The Nuclear Game Theory of the India-Pakistan Crisis.

Then a useful primer, also today, in The New York Times, Why Do India and Pakistan Keep Fighting Over Kashmir?

Lastly, our post from 8.15.17.

Here they are:

The Nuclear Game Theory of the India-Pakistan Crisis

Uri Friedman and Krishnadev Calamur, The Atalntic, February 27, 2019

As President Donald Trump meets with North Korea’s dictator, military escalation in South Asia offers lessons.

What was most revealing about the first day of President Donald Trump’s summit in Vietnam with Kim Jong Un wasn’t the president’s characterization of his private conversation with the North Korean dictator (“Boy, if you could have heard that dialogue, what you would pay for that dialogue”). It wasn’t his refusal to respond to shouted questions about the fact that, back in Washington, D.C., all eyes were on his former lawyer Michael Cohen, who was assailing the president’s character and conduct.

Instead it was what was left unsaid: As Trump sought to persuade Kim to give up his nuclear weapons, enticing his young “friend” with visions of a disarmed North Korea as an “Economic Powerhouse,” India and Pakistan were trading blows in a case study of what conflict looks like when countries successfully obtain nuclear weapons despite international opposition.

The two developments were particularly striking because, as former U.S. officials and experts who have negotiated with Pyongyang over the years have recounted, North Korean often cites India and Pakistan as models of what it ideally wants from the United States: an end to punishment and isolation for pursuing nuclear weapons, tacit recognition of its status as a nuclear-weapons state, and better relations with Washington. That rationale has a cold logic, but holds only as long as North Korea isn’t involved in the kind of back-and-forth that India and Pakistan find themselves in.

(More stories:

Disinformation Is Spreading on WhatsApp in India—And It’s Getting Dangerous

“They said it very clearly,” Joseph DeTrani, a former U.S. intelligence official who engaged in talks with North Korean officials as recently as 2017, told NK News. “Accept us as a nuclear-weapons state and we will be a good friend of the United States. You’ve done it with Pakistan.” The North Koreans wanted roughly the deal India got from the United States, George Perkovich of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace told The Atlantic in describing a 2007 meeting. “What North Korean officials said to me is ‘We’re going to keep our nuclear weapons, and you’re going to end the sanctions and normalize relations and make a peace treaty with us,’” he said in a 2017 interview.

Read: Trump thinks he’s the only one who can fix North Korea

Trump-administration officials insist that their ultimate objective continues to be the “full verified denuclearization” of North Korea, but ahead of the Vietnam summit, they’ve signaled that their near-term goals are far more modest. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has vowed to “reduce the threat from a nuclear-armed North Korea,” while Trump has noted that “as long as there’s no [nuclear and missile] testing, we’re happy.” If the outcome of the Vietnam summit is fundamentally about finding ways to minimize the danger to the United States and the world of living with a nuclear North Korea, the dispute between India and Pakistan is instructive of how geopolitics could change as a result.

Two weeks after a terrorist carried out a suicide attack on a convoy of Indian security forces, killing 40 soldiers, the two countries have taken progressively more aggressive action against each other. New Delhi, blaming Pakistan for the bombing, dispatched the Indian air force to strike what it said was a terrorist training camp in Pakistan. Soon after, Islamabad said it had shot down two Indian jets and captured a pilot.

India and Pakistan have fought multiple conflicts since the end of British colonial rule in 1947 resulted in the partition of the subcontinent. Pakistan’s prime minister and senior Indian officials have said they don’t want to see the situation deteriorate any further, but the risk of miscalculation remains high, amid fears that any misstep could trigger all-out war, the first between the two countries since they both developed nuclear weapons—in fact, the first between two nuclear-armed states, ever.

The situation illustrates the paradox a nuclear arsenal poses: Nonproliferation advocates would argue that the danger of escalation into apocalyptic war is why states should not possess such weapons. But it is precisely because of situations like these that countries such as India and Pakistan will never renounce them.

The ongoing hostility elicits questions, not to mention fears, about the point at which the two states are prepared to resort to using nuclear weapons. It brings to the fore the logic of possessing such weapons, whether states are taken seriously as great powers without them, and indeed whether possession of them limits a nation’s military options, especially when its public is baying for war.

Western nations and nonproliferation groups were aghast when India and Pakistan, in quick succession, declared themselves nuclear-weapons states in 1998 amid worsening relations. International sanctions quickly followed, but were mostly lifted in subsequent years amid tacit acknowledgment of the countries’ newfound military capabilities. Since then, the United States has actively encouraged India’s nuclear program and expressed disquiet about the security of Pakistan’s weapons.

Relations between the neighbors, never particularly good, have stayed tense, though until recently any difficulties were confined to political rhetoric and border skirmishes, with two significant exceptions. Nonproliferation activists point to those two incidents—the Kargil conflict of 1999 and a months-long military standoff along their de facto border following a militant attack on India’s Parliament in 2001—as examples of the perils of conflict between nuclear-armed states.

That there hasn’t been a war between India and Pakistan involving nuclear weapons does not mean it cannot happen. The vast majorities of their respective populations have little to no memory of any of the pre-Kargil conflicts (India has a median age of less than 27; Pakistan’s is less than 23). In India, the dominant media sentiment appears to be that Pakistan needs to be taught a lesson for its support of terrorist groups. The government in New Delhi, facing an anxious public and an upcoming election, could feel compelled to act.

Thus far, nuclear weapons are largely why those earlier clashes, and countless others, didn’t develop into full-scale war. On this and other occasions, the bellicose language from the public and media in the two countries hasn’t publicly been matched by their respective prime ministers—this despite the fact that each country has viewed the other as an existential threat since independence. New Delhi and Islamabad see the possession of nuclear weapons not only as cementing their rightful place in the world as powerful nations, but also as providing a credible deterrent against threats, real and perceived.

That, in effect, is the underlying reason few believe Kim will ever give up nuclear weapons. So while the military escalation in South Asia has sparked little public discussion in Hanoi, its implications have nevertheless been felt there.

. . .

Why Do India and Pakistan Keep Fighting Over Kashmir?

By Vindu Goel, The New York Times, February 27, 2019

Two nuclear-armed siblings with a long history of armed conflict. Two prime ministers facing public pressure for military action. And a snowy, mountainous region that both nations have coveted — and occupied with troops — for more than 70 years.

It was almost inevitable that fighting would break out again between India and Pakistan.

On Wednesday, Pakistani and Indian fighter jets engaged in a skirmish over Indian-controlled territory in the disputed border state of Jammu and Kashmir. At least one Indian jet was shot down, with Pakistan capturing its pilot.

The incursion came just one day after Indian aircraft flew into Pakistan and attacked near the town of Balakot. The Indian government claimed it was striking a training camp for Jaish-e-Mohammed, a terrorist group that was responsible for a Feb. 14 suicide bombing in southern Kashmir that killed at least 40 paramilitary forces. Pakistan has insisted it had no involvement in the suicide attack.

Now there are fears that hostilities could escalate between the two countries, which were created by the bloody partition of British India more than 70 years ago and have co-existed uneasily ever since.

What are the roots of the conflict?

When the British finally gave up their colony of India in August 1947, they agreed to divide it into two countries: Pakistan, with a Muslim majority, and India, with a Hindu majority. (Bangladesh was initially part of Pakistan but gained its own independence in 1971 after a short war between India and Pakistan.)

The sudden separation prompted millions of people to migrate between the two countries and led to religious violence that killed hundreds of thousands.

Left undecided was the status of Jammu and Kashmir, a Muslim-majority state in the Himalayas that had been ruled by a local prince. Fighting quickly broke out, and both countries eventually sent in troops, with Pakistan occupying one-third of the state and India two-thirds.

Although the prince signed an agreement for the territory to become part of India, the United Nations later recommended that an election be held to let the people decide.

That election never took place, and both countries continue to administer their portions of the former princely territory while hoping to get full control of it. Troops on both sides of the “line of control” regularly fire volleys at each other.

Muslim militants have frequently resorted to violence to expel the Indian troops from the territory. Pakistan has backed many of those militants, as well as terrorists who have struck deep inside India — most brutally in a four-day killing spree in Mumbai in 2008 that left more than 160 people dead.

Why did the situation erupt now?

The immediate cause was the Feb. 14 suicide bombing by a young Islamic militant, who blew up a convoy of trucks carrying paramilitary forces in Pulwama in southern Kashmir. It was the deadliest attack in the region in 30 years.

But there are also broader political forces at work. India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, is up for re-election in May, and he is eager to avenge a bombing that has stirred popular outrage.

Pakistan, for its part, has a new prime minister, Imran Khan, who was elected last year with the backing of his country’s powerful military. Mr. Khan wants to show that he can stand up to India, even as the country’s economy is so weak that he is seeking bailouts from Saudi Arabia and China.

Can the United States and other

global powers help calm the situation?

On Tuesday, the American secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, called on leaders in both countries to avoid escalating the situation. He also said that Pakistan must take “meaningful action against terrorist groups’ operating on its soil.”

Under President Trump, American foreign policy has shifted away from Pakistan, a longtime recipient of American aid, toward India, which the administration views as a bulwark against China’s rising influence in Asia.

China, meanwhile, has become a close ally and financial patron of Pakistan. The Chinese urged both countries to exercise restraint after India’s foray into Pakistani airspace.

Indo-Pakistan relations, however, have taken a back seat this week to another thorny foreign policy problem. President Trump is meeting with North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong-un, to discuss the possible dismantling of that country’s nuclear program and how to achieve lasting peace on the Korean Peninsula.

What is likely to happen next?

In a similar episode in 2016, after militants attacked an Indian Army base in Uri, Kashmir, Indian forces crossed the line of control and carried out what the government called a “surgical strike” on terrorist camps there. (The Pakistani government has denied that the attacks occurred.)

“The strike after Uri made sense,” said Myra MacDonald, a former journalist who has written two books on Indo-Pakistan relations. “The Indian government got sympathy from the Western world.”

But now, with India’s plane shot down and pilot captured, the situation could escalate quickly. “It is impossible to get out of such a situation without a retaliatory spiral,” she said.

Sreeram Chaulia, dean of the school of international affairs at O.P. Jindal Global University outside New Delhi, predicted that the military conflict would subside soon.

He worried instead that Pakistan-backed militants would carry out terrorist attacks in India. “The terrorist threat has not gone away,” he said.

Mr. Khan, the Pakistani prime minister, urged India to settle matters through talks. “All big wars have been due to miscalculation,” he said in a televised address. “My question to India is that given the weapons we have, can we afford miscalculation?”

World Campaign post, 8.15.17:

Today is the 70th anniversary of one of the most important events in history. Not just in modern history, but in history.

How well has it been covered? How much do you know about it?

The end of colonialism (in the main) began with the single biggest colony in history, India, the jewel in the crown of the British Empire, partitioned into two nations, India and Pakistan.

After decades of the struggle for independence from Britain led primarily by Gandhi and his non-violent campaign of civil disobedience, India became the largest democracy in the history of the world. It remains so today.

But this was achieved at the price of partitioning parts of India into the nation of Pakistan. This may have reached a point of inevitability but was not inevitable from the outset. And the manner in which it happened was certainly not inevitable.

India was and is primarily Hindu. Pakistan was and is primarily Muslim. The partition led to a mass migration of Hindus and Muslims in both directions when both nations were declared independent on August 15, 1947.

Over a million people died, many more viciously injured and maimed, and millions became refugees. A number of observers who had seen the results of the Holocaust described the above as worse, with women having their breasts cut off, fetuses ripped from their stomachs and roasted on spits.

It was one of the worst spontaneous genocides and humanitarian disasters of all times. It was not worse than the Holocaust of course. But it had a similar impact on the psyche of the subcontinent, the home of the largest population on the planet.

And neither nation has ever recovered. They have been in various states of conflict ever since. Pakistan was torn in half in civil war in 1971 out of which a third nation, Bangladesh emerged, which had been initially part of Bengal before it was partitioned in 1947. The civil war included a mass genocide by the Pakistanis and the intervention of India in support of the new state of Bangladesh. The Kashmir region has been disputed between India and Pakistan since the partition, wars have been fought over it, India, Pakistan and China control parts of it, and it has had its own independence movement. Punjab has had a similar situation.

In India, there is still a large Muslim population among the Hindu majority. Periodically, there has been mass violence and murder. Yet, in some places, the Hindu and Muslim population (and other religious or ethnic groups) coexist peacefully–the places where the scourge of both nations, hunger and poverty and inequality, have been addressed by land reform and other reforms which have brought prosperity for all.

The usual lesson.

But in Pakistan, the disparity between the wealthy and vast majority of poor has remained nearly absolute. Democracy has not flourished; extremist violence has been the norm and international terror has been spawned.

And in India, which has been in the main a model of democracy, other corruption has been endemic, and the modernization of the economy has benefited some, but an enormous population remains poor and hungry. The largest single number of poor and hungry people in the world are in India. Even though in pockets, reforms enacted by democratically elected state governments have led to largely reducing hunger and poverty and increasing equality and stability.

But Hindu nationalism and anti-Muslim bias have been on the rise. Because, well, read the above again. As it always happens, everywhere.

Children are abused with impunity in India and Pakistan. The government of India’s own study has shown that half of all children are sexually abused. Women are less than second class citizens in many parts of both nations. Although India has made more progress, both have made progress with the brave efforts of women, men and famously even children.

And both nations have been led by democratically elected women.

Something the US can’t seem to pull off in its entire history so far.

Yet both women were assassinated, Indira Gandhi in office, Benazir Bhutto while running for it again, as were other heads of state, in office or formerly, because of the instability and extremism in both countries.

And then there’s the nuclear weapons. Lots of them. In India. And Pakistan. Pointed at each other.

Perhaps the most likely place for nuclear war, and spreading to world war, to break out.

With China neighboring on one side and Iran on the other.

And Afghanistan kept unstable by Pakistan in part as a perceived defensive buffer against India. Where the Soviets had invaded, the US had helped the Afghans defeat them, then left them to their miserable poverty, well-armed. Extremism morphed with Pakistanis help. And then 9/11, and the war in Afghanistan, with the Taliban defeated, women liberated, the possibility of development, then the distraction and disaster in Iraq, resurgence of the Taliban in Afghanistan, and so on. With the nukes in Pakistan at risk of falling into the hands of the extremists engendered by the Pakistanis themselves at various points.

And then the matter of nuclear proliferation. North Korea’s program was started with Pakistani help.

India is soon to be the largest nation on earth in population, and the next century will likely be that of India, not China. Or of both, and of the US and Europe, etc.

But India will be the largest country on earth, the largest country in world history.

And Pakistan is and will be huge in population as well, and perhaps the most unstable place on earth.

This is just a short primer. On why one needs to educate oneself as fully as possible about the history and current events regarding the above.

A start is the excellent article in The Observer in London, Why Pakistan and India remain in denial 70 years on from partition, by Yasmin Khan, associate professor of history at Oxford and author of The Great Partition: the making of India and Pakistan.

Linked to the article is another, Partition, 70 years on: Salman Rushdie, Kamila Shamsie and other writers reflect, a revelation in depth and breadth not to be missed.

Here is the article.

Why Pakistan and India remain in denial 70 years on from partition:

The division of British India was poorly planned and brutally carried out, as fear and revenge attacks led to a bloody sectarian ‘cleansing’

“On 3 June 1947, only six weeks before British India was carved up, a group of eight men sat around a table in New Delhi and agreed to partition the south Asian subcontinent.

Photographs taken at that moment reveal the haunted and nervous faces of Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian National Congress leader soon to become independent India’s first prime minister, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, head of the Muslim League and Pakistan’s first governor-general and Louis Mountbatten,the last British viceroy.

Yet the public also greeted this agreement with some cautious hope. Nobody who agreed to the plan realised that partition was unleashing one of the worst calamities of the 20th century. Only weeks later, the full scale of the tragedy was apparent.

The north-eastern and north-western flanks of the country, made up of Muslim majorities, became Pakistan on 14 August 1947. The rest of the country, predominantly Hindu, but also with large religious minorities peppered throughout, became India. Sandwiched between these areas stood the provinces of Bengal (in the east) and Punjab (in the north-west), densely populated agricultural regions where Muslims, Hindus and Punjabi Sikhs had cultivated the land side by side for generations. The thought of segregating these two regions was so preposterous that few had ever contemplated it, so no preparations had been made for a population exchange.

“Do you foresee any mass transfer of population?” one journalist asked Mountbatten at a press conference in Delhi, after the plan was announced. “Personally, I don’t see it,” he replied. “There are many physical and practical difficulties involved. Some measure of transfer will come about in a natural way … perhaps governments will transfer populations. Once more, this is a matter not so much for the main parties as for the local authorities living in the border areas to decide.”

However, people took fright and, in the face of mounting violence, took matters into their own hands. Many did not want “minorities” in their new countries. Others did not want to become “minorities” with all the attendant horrors this now implied. Refugees started to cross over from one side to the other in anticipation of partition. The borderlines, announced on 17 August – two days after independence – cut right through these two provinces and caused unforeseen turmoil. Perhaps a million people died, from ethnic violence and also from diseases rife in makeshift refugee camps.

The epicentre was Punjab, yet many other places were affected, especially Bengal (often overlooked in the commemorations), Sindh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Kashmir and beyond. Lahore – heir to the architecture of Mughal, Sikh and British rule, and famed for its poets, universities and bookshops – was reduced in large quarters to rubble. In Amritsar, home of the Golden Temple, and also known for its carpet and silk weavers, it took more than five years to clear the wreckage. There were more than 600 refugee camps all over the subcontinent, 70,000 women had suffered sexual violence and the issue of the princely states, especially Kashmir, remained unresolved. Many hopes had been cruelly dashed. The act of partition set off a spiral of events unforeseen and unintended by anyone, and the dramatic upheavals changed the terms of the whole settlement.

The stories make us flinch. Bloated and distorted bodies surfacing in canals months after a riot, young pregnant women left dismembered by roadsides. One newspaper report tells of an unnamed man from a village “whose family had been wiped out”, who on meeting Jinnah as he toured the Pakistani camps in 1947, “sobbed uncontrollably”. Up to 15 million people left their homes to begin a new life in India or Pakistan, and by September 1947 the formal exchange of population across the Punjab borderlines had become government policy.

Conscious of the fact that time is running out to record eye- witness testimony from the survivors of 1947, many people have collected memories and oral histories in the past decades. These can be downloaded at the click of a button, and have been collected by volunteers, family members and historians. Partition history used to be all about the high politics and the relative responsibilities of Mountbatten, Jinnah, Gandhi and Nehru – these four men have always towered over the story, and ultimately their animosities and the reasons they failed to agree on a constitutional settlement make them the leading actors of an enduring and gripping drama – but today many historians are far more interested in the fate of refugees in the camps, the ways in which villagers experienced the uprooting of 1947, or how they rebuilt their lives in the aftermath.

There is still a mystery at the dark heart of partition. Ultimately, it remains a history layered with absence and silences, even while many mourn and talk about their own trauma. Nearly every Punjabi family – Indian and Pakistani – can tell a tale about a relative uprooted in the night, the old friends and servants left behind, the nostalgia for a cherished house now fallen into new hands. Far fewer are willing to discuss the role of their own locality in contributing to the violence. Rarely, oral histories tell of culpability and betrayal; more often, guilt and silences stalk the archive.

Who were the killers? Why did they kill? Much evidence points not to the crazy and inexplicable actions of mad, uneducated peasants with sticks and stones, but to well-organised and well- motivated groups of young men, who went out – particularly in Punjab – to carry out ethnic cleansing. These men, often recently demobilised from the second world war, had been trained in gangs and militias, were in the pay of shopkeepers and landlords, and had often been well drilled and well equipped. They took on the police and even armed soldiers on some occasions.

There are evident parallels with Rwanda and Bosnia, in the collapse of old communities and the simplification of complex identities. Militant leaders tried to make facts on the ground by carving out more land for their own ethnic group. They used modern tactics of propaganda and bloodshed that are familiar today. Many newspapers had caricatured the “other” community for decades. Compared with the way Germans look with clear eyes at their past, south Asia is still mired in denial.

Volunteers could be seen marching along the major roads on their way to join the battle in the summer of 1947. Some wore uniforms, were armed with swords, spears and muzzle-loading guns. One gang intercepted on their return from fighting even had an armoured elephant. The militias also worked hand in glove with the local leaders of princely states who channelled funds and arms. They answered to local power brokers and sometimes to the prompts of politicians. This helps explain the scale of the violence.

In other places, it was a case of neighbour turning against neighbour, often in a deluded form of “self-defence” or revenge, sometimes as a cover for resolving old family feuds, for getting back at a mercenary landlord or as a chance to loot. In the main, people were whipped up by demonisation of the other, encouraged by the rhetoric of politicians and a feverish media.

The British government had repeatedly delayed granting freedom in the 1930s, when it might have been more amicably achieved. After waiting decades for freedom, this was a moment of intense anxiety and fear. Propaganda had built up during the preceding war years, especially while Gandhi and the Indian National Congress leaders were shut in prison in the 1940s; Jinnah saw the second world war as a blessing in disguise for this very reason. Ultimately, 1947 became a perfect storm as many contingencies collided.

On the British side, the planning was shoddy and the date was rushed forward by a whole year; the original plan was for a British departure in mid-1948. Mountbatten prioritised European lives and made sure he didn’t get British troops entangled in a guerilla war. And the British bungled the details: there was a sweeping idea behind partition but almost nothing in place to deal with how this unparalleled division would be achieved on the ground. The limited military force put in place in July, the Punjab Boundary Force, was understaffed and spread over a vast distance. This was a textbook case of a power vacuum.

Where did the power lie as the British left and the new states formed? The British come out of the story looking ill-prepared, naive and even callous.

But could the British have settled the competing nationalist visions in south Asia in the 1940s, and could they have created a constitution to please everybody? This is the great hypothetical question. Endless rounds of previous negotiations had ended in disappointment and overlaying new nation states over the grid of messy, large, complex empires was a challenge all over the world.

Many Muslim Leaguers would have accepted power within a federal, decentralised and unified India in 1946, while many members of the Indian National Congress resisted power- sharing schemes. But, ultimately, we just do not know how the alternatives would have worked. In the event, Jinnah pushed for Pakistan, and the final compromise was to create two states by drawing borders across Punjab and Bengal. All the key leaders – including Jinnah, Nehru and Mountbatten – agreed to this plan, and with some relief: they hoped it might actually bring an end to violence and herald a new beginning.

The tragedy of partition is that the stories of extreme violence in 1947 have provided fodder to opposing perspectives ever since, and myths have crystallised around the origins of India and Pakistan. As Gandhi put it in the summer of 1947, “Today, religion has become fossilised.” Many backdated histories have been written after the event, and are present in school textbooks and the national media in Asia. This sweeps aside any appreciation of the hybrid, Indo-Islamic world that flourished before the British began their conquest in the 18th century. The land in which vernacular Sanskrit-based languages were cross- pollinated with Turkish, Persian, and Arabic, in which Rajput princesses married Mughal rulers, and musical and artistic styles had thrived on the fusion of influences from central Asia and local courtly cultures.

This world of more fluid identities and cultures was gradually dismantled throughout the 19th century under British rule and then smashed by partition. It becomes ever harder, today, to imagine the pre-partitioned Indian subcontinent.

In the south Asian case, the historical conflict is now acted out on a different, international stage. India and Pakistan stand frozen in a cold war, with nuclear missiles pointed at each other. At least one billion people living in the region today were not even born when partition took place and south Asia has many more immediate and far more pressing problems: water supply, environmental crisis and adaptation to climate change.

Nonetheless, a sense of shared history, and a more multidimensional understanding of what happened in 1947 is also vital for the future of the region. After 70 years, this anniversary is a valuable moment for reflection and provides an opportunity to commemorate the dead. It may also provide a chance to ask questions, to disrupt some of the cliches, and to think once again about how we tell this history.”