“The Theresa May story: The Tory leader brought down by Brexit”, BBC News

By Brian Wheeler and Gavin Stamp, London, 24 May 2019

Britain’s second female prime minister, like the first, has ultimately been brought down by Conservative in-fighting over Europe.

But Theresa May is unlikely to join Margaret Thatcher in the annals of leaders who left an indelible mark on their country. At least not in the way she might have wanted when she entered Downing Street in July 2016.

Whatever ambitions she had – to reach out to the forgotten parts of the nation, or correct the “burning injustices” in British society – were overshadowed by a single word: Brexit.

Her almost three years in office were entirely defined by Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, and her increasingly desperate efforts to deliver on the outcome of the referendum called by her predecessor David Cameron.

Even her sternest critics had to marvel at her ability to soak up the punishment that came, in wave after wave, from all sides.

Ministerial resignations and parliamentary rebellions that would have spelled the end for a prime minister in normal times seemed to bounce off her. She ploughed on, seemingly oblivious to the chaos around her, telling MPs “nothing has changed” and promising to deliver on the “will” of British people, even as her power over Parliament and control of her warring party drained away to nothing.

It might have been different had she managed to win the 2017 general election.

Image copyrightPA

Image copyrightPABut instead of returning to Downing Street with a huge mandate of her own, as she had expected, she lost her Commons majority and had to rely on the support of Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party.

She never really recovered from this self-inflicted wound, with a sense that many of her MPs were only keeping her in office until she had delivered Brexit before jettisoning her in favour of a more voter-friendly alternative.

At one point, she had to promise she would quit before the next scheduled election in 2022, as she battled to win a no-confidence vote organised by her own MPs.

And then, as the end neared – and she had alienated many MPs by blaming them for the deadlock over Brexit – she was forced, finally, to accept that the party, which had never elected her as leader, did not want her to serve any more.

She offered her own departure as the final sacrifice to her internal critics, telling them she would stand down if they voted for her EU withdrawal deal.

A venerable Tory colleague once described Theresa May as a “bloody difficult woman”.

She wore the label as a badge of honour.

She was said to have a dry wit in private, but her public persona, even when she was trying to lighten up, could be wooden and forced, and even close colleagues were said to have difficulty working out what she was really thinking.

Her single-minded, unshowy and diligent approach to politics enabled her to steadily navigate her way to the very top of a party that had traditionally favoured men from more privileged backgrounds than her own when she had first joined it in the late 1970s.

And despite what it must feel like right now, Brexit will not be her only political epitaph.

Who is Theresa May?

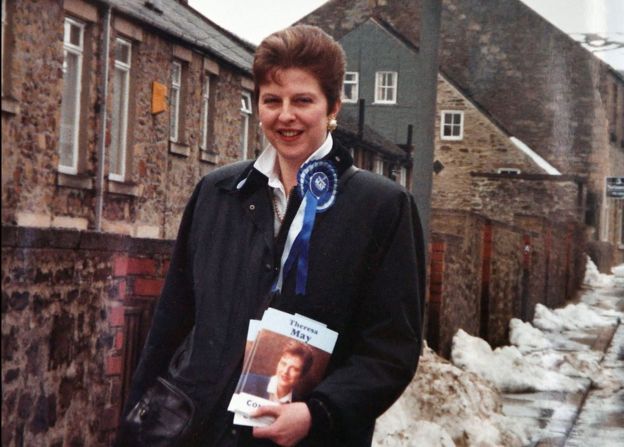

Image copyrightTHERESA MAY

Image copyrightTHERESA MAY- Date of birth: 1 October 1956 (aged 62)

- Jobs: MP for Maidenhead since 1997. Became prime minister in 2016 after serving as home secretary for six years.

- Education: Mainly state-educated at Wheatley Park Comprehensive School with a brief time at an independent school; St Hugh’s College, Oxford

- Family: Married to Philip May

- Hobbies: Cooking – she says she owns more than 150 recipe books. Mountain-walking holidays with her husband. On BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs in 2014, she chose Abba’s Dancing Queen and Walk Like A Man, from the musical Jersey Boys, among her picks, alongside Mozart and Elgar. She chose a subscription to Vogue as her luxury item, reflecting her lifelong love of high fashion.

The daughter of a Church of England vicar, Hubert, who died from injuries sustained in a car crash when she was 25, Mrs May said her father had taught her to “take people as you find them” and “treat everyone equally”.

Born in Eastbourne, East Sussex, but raised largely in Oxfordshire, she attended a state primary, an independent convent school and then a grammar school in the village of Wheatley, which became the Wheatley Park Comprehensive School during her time there.

The young Theresa Brasier, as she was then, threw herself into village life, taking part in a pantomime that was produced by her father and working in the bakery on Saturdays to earn pocket money.

Friends recall a tall, fashion-conscious young woman who, from an early age, spoke of her ambition to be the first woman prime minister.

In 1976, in her third year at Oxford University, she met her husband Philip, who was two years younger than her and president of the Oxford Union, a well-known breeding ground for future political leaders.

They were introduced at a Conservative Association disco by future Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto. Both claim it was “love at first sight”. They married in 1980.

Image copyrightTHERESA MAY

Image copyrightTHERESA MAYThere are no tales of drunken student revelry from Mrs May’s time at Oxford, but friends say she was not the austere figure she would later come to be seen as, suggesting she had a sense of fun and a full social life.

After graduating with a degree in geography, May went to work in the City, initially starting work at the Bank of England and later rising to become head of the European Affairs Unit of the Association for Payment Clearing Services.

Image copyrightTHERESA MAY

Image copyrightTHERESA MAYShe first dipped her toe in the political water in 1992, when she stood in the safe Labour seat of North West Durham, coming a distant second. Her fellow candidates in that contest also included a very youthful Tim Farron, who went on to become a Lib Dem leader.

Two years later, she stood in Barking, east London, in a by-election where – with the Conservative government at the height of its unpopularity – she got fewer than 2,000 votes and saw her vote share dip more than 20%. But her luck was about to change.

The Conservatives’ electoral fortunes may have hit a nadir in 1997, when Tony Blair came to power in a Labour landslide, but there was a silver lining for the party and for the aspiring politician when she won the seat of Maidenhead in Berkshire, having beaten her future chancellor Philip Hammond to be selected as the candidate. It’s a seat she has held ever since.

Image copyrightANDREW PARSONS/I-IMAGES

Image copyrightANDREW PARSONS/I-IMAGESAn early advocate of Conservative “modernisation” in the wilderness years that followed, Mrs May quickly joined the shadow cabinet in 1999, under William Hague, as shadow education secretary and in 2002 she became the party’s first female chairman under Iain Duncan Smith.

She launched a drive to get more women selected as Conservative candidates in winnable seats but antagonised the party’s grass roots by telling them in a conference speech that they were still seen by some as “the nasty party” and had to change their ways.

Some activists struggled to forgive her for that but it was an early sign of her willingness to deliver unpalatable home truths.

As home secretary, she was booed offstage by angry officers at the Police Federation annual conference, after she had told them they should welcome her reforms and “stop pretending” they were being “picked on” by the government.

After Iain Duncan Smith’s brief, chaotic reign as Tory leader, Mrs May held a range of senior posts under his successor Michael Howard.

But she was conspicuously not part of the “Notting Hill set” which grabbed control of the party after its third successive defeat in 2005 and laid David Cameron and George Osborne’s path to power.

She was initially appointed shadow leader of the House of Commons, but gradually raised her standing and by 2009 had become shadow work and pensions secretary.

Nevertheless, her promotion to the job of home secretary when the Conservatives joined with the Lib Dems to form the first coalition government in 70 years was still something of a surprise – given that Chris Grayling had been shadowing the brief in opposition.

The Home Office had proved to be the kiss of death for many a promising political career, but Mrs May refused to let this happen to her.

Image copyrightPA

Image copyrightPAShe became the longest-serving occupant of the office in recent history, staying in the post for six years, and developing a reputation as a tough operator who would always fight her corner.

Despite her liberal instincts in some policy areas, such as stop and search powers for the police, she frequently clashed with the then deputy prime minister and Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg, particularly over her plan to increase internet surveillance to combat terrorism, dubbed the “snooper’s charter” by the Lib Dems.

After one “difficult” meeting with Mr Clegg, he reportedly told Lib Dem minister David Laws: “You know, I’ve grown to rather like Theresa May… She’s a bit of an ice maiden and has no small talk whatsoever – none. I have quite difficult meetings with her. Cameron once said, ‘She’s exactly like that with me too!'”

Crime levels fell and she successfully deported radical cleric Abu Qatada – something she listed as one of her proudest achievements, along with preventing the extradition to America of computer hacker Gary McKinnon.

There was a bitter public row with cabinet colleague Michael Gove in June 2014 over the best way to combat Islamist extremism, which ended with Mr Gove having to apologise to the prime minister and Mrs May having to sack a long-serving special adviser.

Mrs May faced constant criticism over the government’s failure to meet its promise to get net migration down to below 100,000 a year, She persisted with this target when she entered Downing Street, even though she had never come close to meeting it and had faced repeated calls from Tory colleagues to drop it.

Her decision to make life more difficult for illegal immigrants by restricting access to the NHS and accommodation – and vowing to “deport first and hear appeals later” – would also come back to haunt her when she became prime minister.

The Windrush scandal – which saw Commonwealth citizens who had lived in the UK legally for decades being harassed and even deported because they did not have the correct paperwork – led to the resignation of Home Secretary Amber Rudd, although the minister would later return to the cabinet after an inquiry blamed officials for the Windrush fiasco.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESShe became Conservative leader and prime minister in July 2016 without a general election, following the resignation of David Cameron.

Like Mr Cameron, she had been against Brexit but she cleverly managed to keep the Eurosceptics in her party on side during the referendum campaign by keeping a low profile.

She reaped her reward by emerging as the unchallenged successor to Mr Cameron, as other potential rivals fell by the wayside – portraying herself as a steady pair of hands who would deliver the will of the people and take Britain out of the EU in as orderly a fashion as possible.

At 59, she was the oldest leader to enter Downing Street since James Callaghan in 1976 and was the first prime minister since Ted Heath not to have children.

Mrs May has rarely opened up about her private life although she revealed in 2013 that she had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and would require insulin injections twice a day for the rest of her life – something she said she had come to terms with and which would not affect her career.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESShortly before becoming prime minister, in July 2016, she spoke to the Mail on Sunday about the impact that being told they could not have children had had on the couple’s marriage.

One of her first acts, on entering Downing Street, was to sack Chancellor George Osborne, which seemed to signal a clean break with the past. He would go on to get his revenge in his new, post-politics job as Evening Standard editor with a string of hostile front pages.

To the surprise of many, she also rescued Boris Johnson’s career by appointing him foreign secretary, a decision she may have come to regret when he quit the cabinet two years later in protest at her Brexit plans.

She announced that her government would focus on the more neglected parts of Britain and try to help people on modest incomes who were “just about managing” – seen by some as a grab for traditional Labour territory.

She had always insisted it was not in the national interest to seek a mandate of her own in a general election.

Westminster was stunned, then, when on a quiet Tuesday morning in April a lectern was set up in Downing Street for a prime ministerial announcement.

She would be holding a snap election after all, because, she said, the country needed certainty, stability and “strong leadership” following the EU referendum.

Her change of heart had, apparently, come on a walking holiday in Wales, with husband Philip.

With a commanding 20-point lead over Labour in the opinion polls, she saw an opportunity to “strengthen her hand” in the upcoming Brexit negotiations with Brussels.

Despite her evident discomfort with personality politics, she was placed front and centre as the campaign headed out across the country.

Image copyrightPA

Image copyrightPAThere was an early mis-step as she was forced to do a U-turn on one of her key manifesto pledges – social care charges for the elderly in England.

She had to cap the amount of money one individual could be asked to pay, following claims people would have to sell their homes. At a testy press conference she insisted “nothing had changed”.

The Conservatives had underestimated Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, who came across on television as a more genial figure than the dangerous extremist that he had been painted by Tory MPs and their supporters in the press.

Mrs May refused to take part in televised debates with him, and her attempts to project a more human side in interviews sometimes fell flat. She was mercilessly mocked on social media when she told an ITV interviewer the naughtiest thing she had done as a child was to “run through fields of wheat”.

Nevertheless, no-one seriously expected her to lose the election.

The shock at Tory HQ, when the exit poll was announced, pointing towards a hung Parliament, with the Conservatives as the largest party but without an overall majority, rapidly turned to disbelief. But it turned out to be broadly accurate, unlike the opinion polls in the run up to election day.

Mrs May had won the biggest share of the vote for the Conservative Party since Margaret Thatcher’s 1983 post-Falklands election victory.

But Labour had seen the biggest percentage increase in their vote since 1945, drawing in millions of anti-Tory voters from smaller parties, in a surprise return to two-party politics.

Image copyrightPA

Image copyrightPASo instead of returning to Downing Street in triumph, Mrs May was forced to strike a deal with the Democratic Unionist Party, whose 10 MPs agreed to support her in key Commons votes, sweetened by a £1bn public spending boost for Northern Ireland.

The DUP was staunchly Brexit-supporting and it would go on to play a pivotal role in the Brexit dramas she would face as she tried to get her withdrawal deal through Parliament.

Mrs May had backed Remain in the 2016 EU referendum, although she was barely visible during the campaign. Downing Street aides had reportedly nicknamed her “submarine May” for her alleged habit of going missing when Mr Cameron wanted her public backing for the Remain campaign.

Nevertheless, many Leave-voting Tory MPs suspected she did not believe in Brexit, and viewed it as a “damage-limitation” exercise at best.

She did her best to dispel these doubts with her constant mantra “Brexit means Brexit” and her vow to deliver on the “will” of the people as expressed in the referendum.

To the delight of Brexiteer colleagues, and the dismay of pro-Europeans, she set out a harder-than-expected vision for Brexit in a speech at Lancaster House in January 2017.

Three months later she triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, starting the formal two-year process to take Britain out of the 28-nation bloc.

She stressed that Britain would be leaving the EU single market and customs union – and repeatedly declared that Britain would be prepared to walk away from talks with the EU without a deal.

“No deal is better than a bad deal,” joined her list of favourite Brexit phrases, repeated ad infinitum.

But negotiations in Brussels, led by Brexit Secretary David Davis, ran into the sand over the issue of how to prevent the return of a hard border in Northern Ireland.

Hopes of striking a trade deal by Brexit day had also evaporated and there was now talk of a 21-month transition period, to allow more time for negotiations.

Image copyrightEU COUNCIL

Image copyrightEU COUNCILThings came to a head in July 2018 when the Cabinet met at her country retreat, Chequers, to hammer out a joint position on Brexit that would see the UK establish a “common rulebook” with the EU after Brexit.

Within a few days of Mrs May announcing that she had full cabinet backing, Boris Johnson and David Davis had both quit saying this was not the Brexit they had been promised in her Lancaster House speech.

She also had to endure the humiliation of seeing her Chequers deal publicly rejected – and mocked – by EU leaders at a summit in Salzburg, Austria.

There was a brief respite from the grim Brexit grind in the autumn, when she shimmied on stage at the Conservative Party conference to the strains of Abba’s Dancing Queen.

It helped to dispel the memory of the previous year’s conference speech, which had been one of the most disastrous on record, with letters falling off the slogan behind her, an interruption from a comedian and a hacking cough that threatened to derail it altogether.

By now, Brexit had largely pushed all her other domestic priorities to one side, although the prime minister did agree a £20bn long-term funding settlement for the NHS.

In November 2018, she unveiled a draft EU withdrawal agreement, announcing, after a marathon cabinet meeting, that she had the backing of her top team, only to be faced with a string of resignations hours later.

The withdrawal agreement, with an accompanying statement on future relations, was the best and only deal available, she said.

And it would take the UK out of the EU in an “orderly fashion”, with the minimum of disruption for businesses and citizens of EU countries in the EU as well as British expats in EU countries.

But one clause, known as the Irish “backstop”, was proving too much for the increasingly vocal and angry Brexiteer wing of her party, who feared the Remain-voting prime minister was betraying the 17.4 million who had voted to leave the EU.

The backstop was meant to prevent the return of a “hard border” on the island of Ireland if no trade deal had been agreed by the end of the transition period but there was no time-limit on it and no way for the UK to halt it without the EU’s say-so.

Opposition to the backstop was led by the DUP and a previously obscure group of Tory backbenchers, the European Research Group, headed by Jacob Rees-Mogg.

Mrs May had to get her deal through Parliament but her plans for a vote on 10 December were pulled at the last minute, when it became clear she would have suffered a heavy defeat.

Image copyrightPA

Image copyrightPATwo days later, she faced an attempt to remove her as Conservative leader, and prime minister, in a no-confidence vote orchestrated by the ERG.

She survived by 200 votes to 117.

But it was just the beginning of a seemingly never-ending cycle of political torture she would go on to suffer at the hands of her mutinous MPs.

When she did eventually put her deal to a vote in the Commons, it was rejected by 230 votes – the biggest defeat for a government in parliamentary history.

A total of 118 Tory MPs defied orders and voted against the deal but all of them voted to keep her in No 10 24 hours later, when Labour tabled a vote of no confidence in her government.

The Conservatives in Westminster had now splintered into a bewildering array of factions, from those who wanted to stop Brexit, via another EU referendum, to those who wanted a softer Brexit, to those who wanted the UK to leave without a deal at the earliest opportunity.

The one thing that united them was dislike of Theresa May’s deal.

When she returned to the Commons with a slightly tweaked version of it, MPs rejected it again, by a reduced but still hefty margin of 149.

Power was now visibly ebbing away from her, as her divided cabinet openly discussed alternatives to her deal and junior ministers resigned with such regularity that they barely made the news.

Parliament was also flexing its muscles – MPs voted to reject a no-deal Brexit, something Mrs May had always insisted must stay on the table in negotiations with Brussels.

She had to hold a Commons vote on delaying Brexit, something she had repeatedly insisted she would never do.

And she had to rely on the votes of Labour MPs to get it through, after most of the Conservative contingent defied the whip.

She then had to go to Brussels to ask for a delay to Brexit – another thing she had said she would never do – as MPs rejected her deal for a third time.

Britain’s departure date from the EU was written into UK law as 29 March – and Mrs May had insisted, more than 100 times according to some, that it would not change.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPShe laid the blame for the delay squarely at the door of MPs, in a late evening speech from Downing Street, in which she tried to position herself as being on the side of the public who, she said, were “tired of infighting and political games” over Brexit.

It proved to be another misjudgement, antagonising many of the MPs she was trying to persuade to back her deal and leading to accusations she was behaving like a demagogue.

She had to climb down the following day, offering something close to an apology, as she announced the new timetable for Brexit that had been imposed on her by Brussels.

In an attempt to negotiate a Brexit compromise that could pass muster in the Commons, she also reached out to Jeremy Corbyn.

But six weeks of talks with Labour ended without an agreement, an outcome many Tory MPs said was depressingly predictable.

A further humiliation followed when she had to agree to the UK participating in European Parliament elections – something she had previously said would be unacceptable.

The Conservatives barely mounted a campaign to speak of, in contrast to Nigel Farage’s boisterous new Brexit Party.

With the party’s European poll ratings dropping into single figures and would-be successors openly touting their leadership credentials, she made one final attempt to get MPs on side.

She promised them they would get a binding vote on whether to hold another referendum during the passage of the Withdrawal Agreement Bill and would also get to decide on different options for the UK’s future customs arrangements with the EU.

Brexit could be lost if her deal was rejected, she added.

But by now many MPs had given up listening, having reached the conclusion that she was an impediment to the kind of Brexit they craved – or any kind of Brexit.

Well and truly cornered, Mrs May finally had to accept she could not continue “in the job she loved” and her time in Downing Street – barring a brief transition period – was now over.

“I have done my best,” she said, as she announced the resignation from behind a podium outside Number 10.