Message of the Day: Human Rights

Ella C. Thompson, Alex Shields, Alice Paul, Wilma Keams, 1919, The New York Times, June 4, 2019

One hundred years ago today, the US Senate passed the 19th Amendment to make unconstitutional denying the vote on the basis of sex. This completed congressional approval, with ratification and the vote for women following in the next year.

We have commented much and often on this topic. So, today, on this momentous centennial, we go directly to a number of articles on the subject.

The Atlantic begins a series today on the battle for suffrage, starting with the rousing and instructive piece, The ‘Undesirable Militants’ Behind the Nineteenth Amendment, by executive editor Adrienne LaFrance.

The New York Times offers the excellent in-depth opinion piece today, The Crooked Path to Women’s Suffrage, by historian and author, Susan Schulten.

And lastly, from Northeastern University News yesterday, She told the forgotten story of the suffragist who outmaneuvered President Wilson, an interview by Ian Thomsen of Tina Cassidy, author of the new book, Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait? Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote.

Here they are.

“The ‘Undesirable Militants’ Behind the Nineteenth Amendment”

By Adrienne LaFrance, The Atlantic, Jun 4, 2019

A century after women won the right to vote, The Atlantic reflects on the grueling fight for suffrage—and what came after.

Editor’s Note: Read more stories in our series about women and political power.

Some mornings, President Woodrow Wilson would shut his eyes as he rode past the women who had assembled once again outside the White House. Occasionally he tipped his hat to them. He didn’t want a confrontation, but by the spring of 1917 it was clear that they weren’t going away. Wilson had claimed earlier in his presidency that he wasn’t aware women even wanted the vote. Plausible deniability was no longer an option.

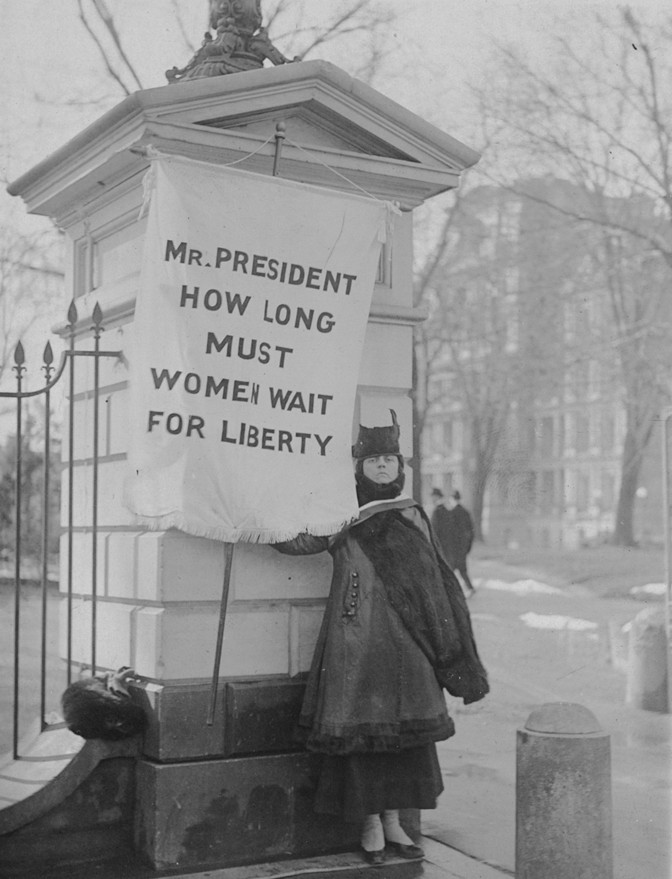

The women had first appeared in the chill of January, silently holding banners that said: “Mr. President, you say liberty is the fundamental demand of the human spirit,” and “Mr. President! How long must women wait for liberty?” Bouts of miserable weather and jeering passersby came and went. The protests continued.

June brought chaos. After months of fragile peace, police started loading the women into paddy wagons. By autumn, hundreds of women had been arrested for obstructing the sidewalk outside the White House. Many of them were sent to prison. Newspapers reported that women were tortured at Occoquan, the Virginia workhouse where several prominent suffragists served time. The idea was “to break us down by inflicting extraordinary humiliation upon us,” Eunice Brannan told The New York Times after her release, in November. Brannan and others described being beaten repeatedly, dragged down stairs, thrown across rooms, kicked, manacled to prison-cell bars, denied toothbrushes, and forced to share a single bar of soap. Drinking water came from a dirty pail that sat in a common area. The guards, some of them marines from nearby Quantico, warned the women they’d be gagged and put in straitjackets if they spoke. Bedding was never washed, and the beans and cornmeal served to prisoners were crawling with maggots. “Sometimes the worms float on top of the soup,” one woman wrote in an affidavit. “Often they are found in the cornbread.” It wasn’t until the following spring that the D.C. Court of Appeals deemed the arrests unconstitutional.

By then 26 women had departed for a railroad tour of the United States, all the way wearing replicas of their prison garb—blue calico tunics with washrags pinned to belts. Their message was the same from Chattanooga to New Orleans; Denver to Milwaukee; San Francisco back to Hartford, Boston, and New York: We just want to vote. Please help us. How long must women wait for liberty?

MORE IN THIS SERIES

On June 4, 1919, these women and dozens of others poured into the U.S. Senate gallery to watch the final vote on the Nineteenth Amendment, which would guarantee them the right to vote. When it passed, they broke into a roaring applause. For two full minutes, senators made no attempt to quiet them. After that, they got back to work. At least 36 states had to ratify the amendment for it to be made official. This took 14 months, just in time for women to vote in the 1920 election.

Before women could win the right to vote, they had to convince people to take them seriously. In the discombobulated decades after the Civil War, American men occasionally found themselves making public arguments against suffrage—brushbacks that were issued casually, even lazily. Girls aren’t smart enough to make a big decision like this. All you’ll do is cancel out your husband’s vote. You’re too pure for politics. Most women don’t actually want this. I’ll buy you another new toy instead. It’s just too expensive to have this many voters. Um, we’re all out of voting machines. Or, as The New York Times declared in 1913, “all the rumpus about female suffrage is made by a very few of our disoriented sisters.”

Wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong, so wrong. But understandable. The powerful are often blind to the stakes and momentum of a political revolution until it’s too late.

When it became clear that suffragists wouldn’t back down, the arguments against them took on an apocalyptic hue. The men and women who opposed the movement issued grave warnings. Banner-making and clubhouse meetings upstate may have been tolerable, even cute, but earlier stirrings had given way to more radical behaviors. During the time women could be found picketing outside the White House, they were also lighting liberty bonfires, parading in the streets, and refusing to eat. By the eve of World War I, suffragists weren’t just a political nuisance that could be dismissed with a newspaper column. Instead, critics yowled that they were instigating a “petticoat coup,” destroying the family unit, and unraveling the very fabric of civil society. Newspapers described them as “undesirable militants,” “unwomanly,” “shameless,” “pathological,” and “dangerous.” Women’s political power—whether they have it, how they get it—has never been about elections alone.

The theologian Lyman Abbott, writing for The Atlantic in 1903, described women who would attempt “man’s function” as “monstrosities of nature,” doomed to inferiority anyway. Such arguments fueled women’s rage and firmed their resolve. “Of course, we enjoyed irritating them,” Doris Stevens wrote in her 1920 book, Jailed for Freedom. “Militancy is as much a state of mind, an approach to a task, as it is the commission of deeds of protest. It is the state of mind of those who in their fiery idealism do not lose sight of the real springs of human action.”

A century later, Americans are only just beginning to reckon in earnest with the complexities of the suffrage movement’s victory. Many of the white women who are widely remembered as its heroines refused to fight for the black women who risked their lives for the cause. Some of those same white women had fought vocally against the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave black men the right to vote in 1870, saying that white women deserved to vote instead. Many of the white women held at Occoquan complained about the black women who slept in the cots beside them, citing integration as evidence of intolerable prison conditions. Suffragists in Washington, D.C., refused to let black women march alongside them in their parades. (In 1913, the journalist Ida B. Wells, who had recently co-founded the NAACP, famously marched with the white women from her state’s delegation anyway.) Women finally secured the right to vote nationwide in 1920, but black women were for decades after that routinely turned away from the ballot box. Only in 1965, with the Voting Rights Act, and with subsequent court decisions, were the tools of disenfranchisement that targeted people of color—including poll taxes and literacy tests—outlawed.

The centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment’s passage is an occasion for celebration, but it is also a cause for inquiry. Americans have again arrived at a political and cultural flash point in which women are playing a transformative role. More women than ever before ran for Congress and for governor last year. More women than ever before are now serving in the House and in the Senate. So far six women are running for president—the most for a major-party nomination in American history. (The previous record was two.) That’s why, to deepen The Atlantic’s coverage of the 2020 presidential election, we’re launching a series over the next several months that looks back on the battle for suffrage, to better understand how we reached this political moment, and where it may lead. Today you can read Emma Green’s story on the activists from either pole of the abortion debate who see themselves as the rightful inheritors of the early women’s movement. You can also read Annika Neklason’s exploration of The Atlantic’s archives to see how we covered the suffrage movement at the time. (Spoiler: Our record is not exactly great.) Look for voting-themed clues in our crossword puzzle all week. And in the days and months to come, we’ll publish many more stories in this series about the stakes of this political moment, and how women are defining it.

Fraud and intimidation still occur on Election Day. The social structures built on the assumption that women would be forever excluded from political and professional spheres remain rigidly in place. In this country and around the world, people refuse to acknowledge the forces and systems that work against women. People continue to fight over what it means for women to have political power, or whether they truly have it. The feminist movement is as fractured as ever, stunted by many of the same forces that complicated the fight for voting rights a century ago. No woman has been president of the United States. The pressing question isn’t just what all of this means for women, but what it means for everyone. Women have been allowed to vote for nearly 100 years now. The real work is just beginning.

Adrienne LaFrance is the executive editor of The Atlantic. She was previously a senior editor and staff writer at The Atlantic, and the editor of TheAtlantic.com.

. . .

“The Crooked Path to Women’s Suffrage”

By Susan Schulten, Opinion, The New York Times, June 4, 2019

The Senate ratified the 19th Amendment a century ago. What took so long?

Exactly a century ago on Tuesday, the Senate passed the 19th Amendment, which forbade states from denying the right to vote on the basis of sex. While ratification would require another year, female suffrage had won its greatest and most permanent victory. That final vote was all the more remarkable given that the Senate had recently rejected the amendment not just once, but twice. The shift of just a few senators on the third vote in early June forever transformed American electoral politics.

Some of those senators who changed their vote realized that recent suffrage victories at the state level brought more women into their constituencies. Others responded to pressure from President Woodrow Wilson, a late convert to the cause. In January 1918, he endorsed the amendment as a demonstration of America’s moral mission, but also something owed to women for shouldering the burdens of World War I at home. Just as African-American military service in the Civil War advanced black suffrage rights, women’s work in the Great War advanced their political rights.

The amendment’s passage capped a long struggle with striking geographical patterns, shown by a series of maps that marked the movement’s progress. In the 1840s, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott convened several hundred women in Seneca Falls, N.Y., to demand the vote as a human right. In the aftermath of the Civil War, suffragists linked their struggle to that of the Southern freedmen. But while Frederick Douglass proved a crucial ally at Seneca Falls, other men argued that woman’s suffrage detracted from the far more urgent quest to enfranchise former slaves. As the white abolitionist Wendell Phillips stated: “One question at a time. This hour belongs to the Negro.”

Such a strategy made sense, for blacks faced existential threats of discrimination and violence after emancipation. This dire situation led congressional Republicans to draft the 14th and 15th Amendments, which enshrined rights for black men by defining them as citizens. Yet by granting citizenship to all men, the amendments marginalized women. White suffragists such as Stanton responded with outrage that black men — whom they considered racially inferior — were enfranchised before them.

Despite this rejection of female suffrage at the federal level after the Civil War, the movement claimed smaller victories in the sparsely settled West. Wyoming, Utah, Colorado and Idaho extended voting rights to women in the late 19th century, less out of an enlightened sense of equality than for partisan purposes: leaders in the Utah Territory initially granted women the vote in 1870 in the hopes of combating anti-Mormon measures, while in Colorado a political alliance extended suffrage rights in 1896 to strengthen the short-lived Populist movement.

By the turn of the century the movement had reached a crossroads. The two foremost organizations — the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association — merged as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, but its aging leadership counted few successes outside the West. And just as the issue of women’s suffrage stagnated at the turn of the century, black citizenship rights were being systematically dismantled: The former slave states disfranchised African-American men through terror but also through ostensibly legal measures such as poll taxes and literacy tests.

A new strategy to expand woman’s suffrage emerged in 1900 when the new organization elected Carrie Chapman Catt as its president. Catt avoided the rhetoric of gender equality, and instead tapped the more prosaic sentiment that women should be permitted to vote as mothers and as “municipal housekeepers.” This strategy helped at first — over the next few years women won the right in several states to vote on local and state ordinances regulating taxation, schooling and the sale of alcohol. Yet the close association of women with temperance may have been counterproductive, generating even more opposition to “the woman vote.” And though several states considered the issue between 1893 and 1910, not a single one extended full voting rights to women.

Given this resistance, the National American Woman Suffrage Association began to lobby state legislatures while also canvassing towns, wards and precincts. It abandoned its longstanding call for an education requirement for voting in order to broaden its reach beyond the middle class. Similarly, it forged alliances with trade unions, prompting Samuel Gompers, the conservative president of the American Federation of Labor, to support female suffrage.

But while expanding its networks, the association also argued that white women, armed with the franchise, would serve as a bulwark against black and immigrant votes. At the same time, though, Southern white opponents of women’s suffrage also made racial appeals by arguing that the movement would empower Southern black women, an absolutely unacceptable prospect at the height of Jim Crow.

Perhaps the most notable convert to woman’s suffrage was Theodore Roosevelt. In 1911, he wrote sympathetically to a leading opponent of suffrage that women “do not really need the suffrage although I do not think they would do any harm with it. Their needs are along entirely different lines, and their duties are along entirely different lines.” A year later, when Roosevelt sought to recapture the presidency on the new Progressive Party ticket, he reassured the social activist Jane Addams that he backed women’s suffrage “without qualification or equivocation.”

Equally important was the adoption of savvy techniques to advertise suffrage through billboards, newspapers, pamphlets, mass meetings and parades. By the early 1910s, America was awash in suffrage propaganda that kept the issue in the news. After a successful campaign in California in 1911, suffrage organizations flooded the public with maps in an effort to export the undeniable momentum in the West to rest of the country.

When The New York Times published one such suffrage map in 1913, a Massachusetts reader responded that “woman suffrage has been adopted only by the crude, raw, half-formed commonwealths of the sagebrush and the windy plains, whence have come in endless procession foolish and fanatical politics and policies for a generation or two.”

Given the intransigence in the South and East, the 1915 effort to grant women the right to vote in the nation’s largest state, New York, drew tremendous attention. The National American Woman Suffrage Association had even moved its headquarters from Ohio to New Yorkto symbolize its commitment to the “Empire State Campaign.” To fuel support, the artist Henry Mayer portrayed suffrage on an eastward march, upending assumptions about the westward progress of civilization.

Pro-suffrage groups were not the only ones using maps to promote their cause. The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage reminded readers that the true test of support for woman’s suffrage was population, not geographical area. Measured by population, the occasional Western victories were vastly outweighed by the states that had defeated suffrage, especially New York. By labeling this a movement of “double suffrage,” the organization implied that women’s votes were redundant, pointlessly enlarging the electorate by replicating the male vote. To anti-suffragists, women did not need the vote because they were politically represented through their husbands, sons and fathers.

The initial failure of suffrage in New York highlighted the limits of the state level campaigns and revived the quest for a federal amendment. Leading this drive was Alice Paul, who parted with the National American Woman Suffrage Association to adopt a more forceful approach. In the 1916 election, she urged voting women in the West to hold the Democratic Party accountable for the lack of progress on a suffrage amendment. By defeating Wilson and congressional Democrats, she argued, women would flex their political muscle, demonstrating but also amplifying their power.

Though Wilson was re-elected, the anticipation of female voting power did change behavior. In 1917 women won the vote in North Dakota and Nebraska, but also in Eastern states (Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana) and the Southern state of Arkansas. The solidly anti-suffrage East and South had been broken. Then, in the fall of 1917, New York again considered a referendum to grant women full voting rights. While the powerful Tammany Hall political machine had ensured the measure’s defeat in 1915, a wellspring of support among New York City Democrats secured its passage. That support grew partly from a grass-roots campaign across the five boroughs, as shown in this postcard sent to a male voter.

New York proved a turning point, for it marked the largest victory in the state-level campaigns. Within a few months, Wilson had come around to supporting the federal amendment. But his decision was also influenced by his relationship to the suffrage movement during the Great War. In 1917, Catt, the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, abandoned her prior pacifism so that her group would not be considered unpatriotic in a war that brutally suppressed dissent.

Alice Paul rejected Catt’s wartime strategy. She not only opposed the war, but openly picketed “Kaiser Wilson” in one of the first White House protests and an early example of nonviolent resistance. Paul and her National Woman’s Party paid dearly for their actions, enduring attacks and jail sentences to publicize the hypocrisy of a nation fighting to extend democracy abroad while denying those same rights to women at home.

Scholars debate whether Catt’s accommodation or Paul’s resistance influenced President Wilson. In fact, it was the combination of the two that forced Wilson to recognize woman’s suffrage as a moral right that would also advance his reform agenda. Though previously noncommittal — even resistant — by January 1918 Wilson vigorously supported the amendment, which was then under debate in the House of Representatives.

The subsequent vote tells us much about the path of political change. The amendment had failed in the House in 1915, but now reached the necessary two-thirds majority. More specifically, 56 of the congressmen who changed their vote from no to yes represented states that had enfranchised women in 1917. Their seats — and their political futures — were now determined by a transformed electorate.

Yet congressmen in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio and across the South remained staunchly opposed to the amendment. Overall, congressional Democrats were evenly split while Republicans supported it by a wide majority. And while suffragists continued to make state-level gains, during the war voting rights for women were actually vetoed or overturned in Ohio, Vermont and Indiana.

With victory in the House secured, attention turned to the Senate. In September, the president traveled to Capitol Hill with almost every member of his cabinet to demonstrate support for the amendment. The Senate was unmoved, and defeated the measure. That November, three more states joined the suffrage column, which brought the total number of electoral votes in states with equal voting rights to 237. Two anti-suffrage senators were defeated in that election, yet when the Senate reconvened in early 1919 the amendment was yet again rejected.

Opponents reiterated that a federal amendment violated state rights, and that enfranchising black women would threaten the white power structure of the South. This stalwart Southern and Eastern opposition might have buried the amendment entirely. But in those last few months, more states granted women limited voting rights, which in turn forced a realignment in the Senate. Though highly distracted by the peace negotiations in Paris, President Wilson managed to wrangle the last vote needed to reach a two-thirds majority on June 4, 1919.

If the woman’s suffrage movement challenged certain power structures, it benefited from and reaffirmed others. It was not above exploiting class and racial divisions to advance its agenda. Once ratified, the 19th Amendment offered little hope to African-American women in the South, who remained marginalized and disfranchised. Yet the movement transformed American democracy by vastly enlarging the electorate and forcing a fundamental recognition of women as political actors.

Sources: Eleanor Flexner and Ellen Fitzpatrick, “Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States”; Paula Baker, ed., “Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited”; David Blight, “Frederick Douglass”; Margaret Finnegan, “Selling Suffrage: Consumer Culture and Votes for Women”; Christine Dando, “Women and Cartography in the Progressive Era”; John Milton Cooper Jr., “Woodrow Wilson”; Woodrow Wilson, Address to the Senate, Sept. 30, 1918.

Susan Schulten is a historian at the University of Denver and the author, most recently, of “A History of America in 100 Maps.”

. . .

“She told the forgotten story of the suffragist who outmaneuvered President Wilson”

By Ian Thomsen, Northeastern University News, June 3, 2019

Tina Cassidy is author of the new book, Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait? Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote

On June 4, 1919, the United States Senate passed and sent onto the states for ratification a law to grant voting rights to women. The 19th Amendment, which would be made official the following year, was pushed through by President Woodrow Wilson, who called a special congressional session.

Alice Paul, a Quaker from New Jersey, was the unlikely leader of the women’s suffrage movement. The Boston Globe via Northeastern University archives.

But Wilson’s support came reluctantly. He capitulated after years of protests engineered by 34-year-old Alice Paul, the unlikely leader of the suffrage movement. Paul and her followers endured imprisonment, hunger strikes, and beatings before creating the public outcry that forced Wilson to see it their way.

Journalist Tina Cassidy, a Northeastern graduate and author of the new book, Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait? Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote, says that the nonviolent strategy of women’s suffrage served as an example for future political causes.

“Gandhi witnessed one of the nonviolent protests that Alice Paul was involved with in England, and he was certainly inspired by these women,” Cassidy says. “Nonviolent protest was also foundational to the civil rights movement in America. Their principles show us that you can affect change without hurting other people.”

Cassidy shared her insights on the 100th anniversary of the congressional action that enabled women to vote.

Who was Alice Paul, and how did she become a suffragist?

Alice Paul was brought up in New Jersey on Quaker values, which are based on equality, racial and gender equality. As a young woman, she went to England to study social justice. It was there that she ran into the Pankhursts (Emmeline and Christabel), who were leading the movement in the United Kingdom to win voting rights for women.

Women staged protests throughout the United States with the goal of pressuring Woodrow Wilson. The Boston Globe via Northeastern University archives.

She was so horrified by the way they were treated by the audience, with people shouting, and singing over them, and throwing things—she’d never seen people treated that way. She was so captivated by this moment that it totally changed her life. She decided to join the Pankhursts’ movement in the U.K. for the vote, and she learned everything that she possibly could from their social change movement, and then brought it back to America.

She realized that being polite and asking sweetly for the right to vote was not getting women anywhere, and that radical tactics were necessary. For a woman that might mean standing on a street corner holding a sign, or speaking out from a stage—these were considered radical acts.

While in prison in the U.K., she learned that hunger strikes were an effective way to get attention and to bring sympathy to the cause. But I think she also became hardened, and really understood that she would have to develop a protective shell to get through the work, and that it was going to involve a great deal of resilience, and determination, and persistence.

Alice Paul went on hunger strikes while in prison, which led to numerous force feedings. How were these feedings administered a century ago?

It was terrible. It was horrific. The prison wardens would strap her hands down, and they would put a towel or sheet over her head and neck to pin them back. And then they would take a tube and put it up her nose; and with a funnel at the top of it, they would slide milk and eggs down the tube. This did not work smoothly. It was often a glass tube, and she suffered abrasions. She would vomit up the food. She also fought at having the the tube inserted and was wounded by that.

It was torture, and it brought sympathy to the movement. It really backfired on officials who insisted on the forced feedings.

She suffered her whole life from the after-effects. It seems as if her sense of taste and smell were damaged. If you can’t smell food, it’s not always appetizing. So she was always frail and never really ate enough, and she also had some digestive troubles that could have been related.

What role did Woodrow Wilson play in the struggle, and what did it reveal about him and his presidency?

President Woodrow Wilson was opposed to equal voting rights for women—until the suffragists boxed him in politically. The Boston Globe via Northeastern University archives.

As a professor at Bryn Mawr College, he thought it was ridiculous to have to teach women, he thought it was beneath him. He also believed that suffrage was the root of all evil.

Woodrow Wilson considered himself a moral president, and yet he did not believe that women should vote. He called himself a moral president, and yet he segregated the civil service in one of his first acts as President.

He created [modern American] segregation. He said that African-Americans and white Americans could not eat at the same table in a federal building; that black customers at the post office would have to go to a special window and be served by black employees; that if you wanted a government job, you had to submit a photograph with your application so that the government could know if you were black or white. That is a legacy that has greatly damaged the nation.

He was so focused on foreign affairs and the Great War that he did not pay enough attention to the needs at home; many of those needs were about inequality in America. He turned his back on that and actually inflamed it in many ways.

Did Alice Paul and her group engage personally with Wilson?

It is a very odd thing to consider that back then, in the early 19-teens, you can literally walk in the door of the White House and ask to meet with the president. And this was in part Woodrow Wilson’s doing: He wanted a transparent government.

The Boston Globe via Northeastern University archives

So these women had many, many meetings with him, especially during the first four years of his presidency.

Unfortunately, as great as that might be that they had access to the President, meeting with him so many times had no effect.

His answer was always the same. I’m too busy. This is unimportant. Giving women the vote is at the bottom of the list of things that I need to focus on. He had his own agenda, and he was sticking to it. And he was really unwilling to change in some ways. He was also affronted by the fact that these women had the audacity to ask for voting rights.

Wilson’s stubbornness was supported by his wife.

The second First Lady, Edith Wilson, shared his view, even though she was a successful and independent businesswoman in Washington before he met her. I just think it was a major change for people to get their head around, that women should be allowed to vote.

How did World War I influence the voting rights movement?

World War I absolutely changed how lots of people viewed the women’s movement. Initially, people who considered themselves patriotic thought it was deplorable that women would protest outside the White House during the war. But as the war went on, people began to understand that we couldn’t set ourselves up as a beacon of democracy when we did not have true democracy in America.

I think Americans really understood the hypocrisy, that so much was being asked of women, they were sacrificing their own sons and husbands on the battlefield, and it wasn’t right that they didn’t have a say in any of it at the ballot box. So the war loomed over the entire movement.

Eventually public opinion came around, and more people agreed with the idea that women should vote. Wilson was a lame-duck president, he was boxed into a corner, and he believed that his Democratic Party would lose if they opposed women’s suffrage. It was a political decision on his part; it was not a moral epiphany. He just said, fine, there’s enough support, let’s go ahead and allow Congress to pass it and the states to ratify the amendments.

Alice Paul [1885-1977] lived to the age of 92. What became of her after her big victory?

What’s amazing is that after the 19th amendment was ratified, Alice Paul could have hung up her hat, put her feet up, and had what we might consider a normal life. Instead, she went to law school, and just three years later she wrote the Equal Rights Amendment. She dedicated the rest of her life to legislation that would promote equality. It’s astonishing to think that giving women the vote was not enough for her.

Alice Paul was a very slight, quiet, reserved woman, and the fact that she could transform herself from that humble beginning to become the leader of a movement that would enfranchise half of the American population is profound. There are lessons in there for all of us.

- “UN inquiry finds Russia’s deportations of 20,000 Ukrainian children amounts to crimes against humanity “, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Reuters

- “Brooks and Capehart on Trump’s decision to launch strikes on Iran”, PBS NewsHour

- Issue of the Week: War

- “The Original”, The New Yorker

- “Big Change Seems Certain in Iran. What Kind Is the Question”, The New York Times

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017