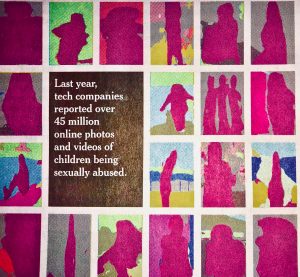

Pictures of child sexual abuse have long been produced and shared to satisfy twisted adult obsessions. But it has never been like this: Technology companies reported a record 45 million online photos and videos of the abuse last year.

More than a decade ago, when the reported number was less than a million, the proliferation of the explicit imagery had already reached a crisis point. Tech companies, law enforcement agencies and legislators in Washington responded, committing to new measures meant to rein in the scourge. Landmark legislation passed in 2008.

Yet the explosion in detected content kept growing — exponentially.

An investigation by The New York Times found an insatiable criminal underworld that had exploited the flawed and insufficient efforts to contain it. As with hate speech and terrorist propaganda, many tech companies failed to adequately police sexual abuse imagery on their platforms, or failed to cooperate sufficiently with the authorities when they found it.

Law enforcement agencies devoted to the problem were left understaffed and underfunded, even as they were asked to handle far larger caseloads.

The Justice Department, given a major role by Congress, neglected even to write mandatory monitoring reports, nor did it appoint a senior executive-level official to lead a crackdown. And the group tasked with serving as a federal clearinghouse for the imagery — the go-between for the tech companies and the authorities — was ill equipped for the expanding demands.

A paper recently published in conjunction with that group, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, described a system at “a breaking point,” with reports of abusive images “exceeding the capabilities of independent clearinghouses and law enforcement to take action.” It suggested that future advancements in machine learning might be the only way to catch up with the criminals.

In 1998, there were over 3,000 reports of child sexual abuse imagery.

Just over a decade later, yearly reports soared past 100,000.

In 2014, that number surpassed 1 million for the first time.

Last year, there were 18.4 million, more than one-third of the total ever reported.

Those reports included over 45 million images and videos flagged as child sexual abuse.

The Times reviewed over 10,000 pages of police and court documents; conducted software tests to assess the availability of the imagery through search engines; accompanied detectives on raids; and spoke with investigators, lawmakers, tech executives and government officials. The reporting included conversations with an admitted pedophile who concealed his identity using encryption software and who runs a site that has hosted as many as 17,000 such images.

In interviews, victims across the United States described in heart-wrenching detail how their lives had been upended by the abuse. Children, raped by relatives and strangers alike, being told it was normal. Adults, now years removed from their abuse, still living in fear of being recognized from photos and videos on the internet. And parents of the abused, struggling to cope with the guilt of not having prevented it and their powerlessness over stopping its online spread.

Many of the survivors and their families said their view of humanity had been inextricably changed by the crimes themselves and the online demand for images of them.

“I don’t really know how to deal with it,” said one woman who, at age 11, had been filmed being sexually assaulted by her father. “You’re just trying to feel O.K. and not let something like this define your whole life. But the thing with the pictures is — that’s the thing that keeps this alive.”

The Times’s reporting revealed a problem global in scope — most of the images found last year were traced to other countries — but one firmly rooted in the United States because of the central role Silicon Valley has played in facilitating the imagery’s spread and in reporting it to the authorities.

While the material, commonly known as child pornography, predates the digital era, smartphone cameras, social media and cloud storage have allowed the images to multiply at an alarming rate. Both recirculated and new images occupy all corners of the internet, including a range of platforms as diverse as Facebook Messenger, Microsoft’s Bing search engine and the storage service Dropbox.

An agent with a task force in Kansas reviewing messages a suspect sent to a child. An officer carrying away a hard drive from a home in Salt Lake City.

Kholood Eid for The New York Times

In a particularly disturbing trend, online groups are devoting themselves to sharing images of younger children and more extreme forms of abuse. The groups use encrypted technologies and the dark web, the vast underbelly of the internet, to teach pedophiles how to carry out the crimes and how to record and share images of the abuse worldwide. In some online forums, children are forced to hold up signs with the name of the group or other identifying information to prove the images are fresh.

(To report online child sexual abuse, contact the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at 1-800-843-5678.)

With so many reports of the abuse coming their way, law enforcement agencies across the country said they were often besieged. Some have managed their online workload by focusing on imagery depicting the youngest victims.

“We go home and think, ‘Good grief, the fact that we have to prioritize by age is just really disturbing,’” said Detective Paula Meares, who has investigated child sex crimes for more than 10 years at the Los Angeles Police Department.

In some sense, increased detection of the spiraling problem is a sign of progress. Tech companies are legally required to report images of child abuse only when they discover them; they are not required to look for them.

After years of uneven monitoring of the material, several major tech companies, including Facebook and Google, stepped up surveillance of their platforms. In interviews, executives with some companies pointed to the voluntary monitoring and the spike in reports as indications of their commitment to addressing the problem.

But police records and emails, as well as interviews with nearly three dozen local, state and federal law enforcement officials, show that some tech companies still fall short. It can take weeks or months for them to respond to questions from the authorities, if they respond at all. Sometimes they respond only to say they have no records, even for reports they initiated.

And when tech companies cooperate fully, encryption and anonymization can create digital hiding places for perpetrators. Facebook announced in March plans to encrypt Messenger, which last year was responsible for nearly 12 million of the 18.4 million worldwide reports of child sexual abuse material, according to people familiar with the reports. Reports to the authorities typically contain more than one image, and last year encompassed the record 45 million photos and videos, according to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

All the while, criminals continue to trade and stockpile caches of the material.

The law Congress passed in 2008 foresaw many of today’s problems, but The Times found that the federal government had not fulfilled major aspects of the legislation.

The Justice Department has produced just two of six required reports that are meant to compile data about internet crimes against children and set goals to eliminate them, and there has been a constant churn of short-term appointees leading the department’s efforts. The first person to hold the position, Francey Hakes, said it was clear from the outset that no one “felt like the position was as important as it was written by Congress to be.”

The federal government has also not lived up to the law’s funding goals, severely crippling efforts to stamp out the activity.

Congress has regularly allocated about half of the $60 million in yearly funding for state and local law enforcement efforts. Separately, the Department of Homeland Security this year diverted nearly $6 million from its cybercrimes units to immigration enforcement — depleting 40 percent of the units’ discretionary budget until the final month of the fiscal year.

Alicia Kozakiewicz, who was abducted by a man she had met on the internet when she was 13, said the lack of follow-through was disheartening. Now an advocate for laws preventing crimes against children, she had testified in support of the 2008 legislation.

“I remember looking around the room, and there wasn’t a dry eye,” said Ms. Kozakiewicz, 31, who had told of being chained, raped and beaten while her kidnapper live-streamed the abuse on the internet. “The federal bill passed, but it wasn’t funded. So it didn’t mean anything.”

Further impairing the federal response are shortcomings at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which reviews reports it receives and then distributes them to federal, state and local law enforcement agencies, as well as international partners.

The nonprofit center has relied in large measure on 20-year-old technology, has difficulty keeping experienced engineers on staff and, by its own reckoning, regards stopping the online distribution of photos and videos secondary to rescuing children.

“To be honest, it’s a resource and volume issue,” said John Shehan, a vice president at the center, which was established 35 years ago to track missing children. “First priority is making sure we’re assessing the risk of the children. We’re getting this information into the hands of law enforcement.”

Representative Debbie Wasserman Schultz, a Democrat from Florida who was an author of the 2008 law, said in an interview that she was unaware of the extent of the federal government’s failures. After being briefed on The Times’s findings, she sent a letter to Attorney General William Barr requesting an accounting.

Stacie B. Harris, the Justice Department’s coordinator over the past year for combating child exploitation, said the problem was systemic, extending well beyond the department and her tenure there. “We are trying to play catch-up because we know that this is a huge, huge problem,” said Ms. Harris, an associate deputy attorney general.

The fallout for law enforcement, in some instances, has been crushing.

When reviewing tips from the national center, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has narrowed its focus to images of infants and toddlers. And about one of every 10 agents in Homeland Security’s investigative section — which deals with all kinds of threats, including terrorism — is now assigned to child sexual exploitation cases.

“We could double our numbers and still be getting crushed,” said Jonathan Hendrix, a Homeland Security agent who investigates cases in Nashville.

The Cutting Edge

The videos found on the computer of an Ohio man were described by investigators as among “the most gruesome and violent images of child pornography.”

One showed a woman orally forcing herself on a girl who was then held upside down by the ankles in a bathroom while “another child urinates” on her face, according to court documents.

Another showed a woman “inserting an ice cube into the vagina” of a young girl, the documents said, before tying her ankles together, taping her mouth shut and suspending her upside down. As the video continued, the girl was beaten, slapped and burned with a match or candle.

“The predominant sound is the child screaming and crying,” according to a federal agent quoted in the documents.

The videos were stored in a hidden computer file and had also been encrypted, one common way abusive imagery has been able to race across the internet with impunity.

Restraints prepared for a suspect in Wichita, Kan. An officer’s view into the interrogation room.

Kholood Eid for The New York Times

Increasingly, criminals are using advanced technologies like encryption to stay ahead of the police. In this case, the Ohio man, who helped run a website on the dark web known as the Love Zone, had over 3 million photos and videos on his computers.

The site, now shuttered, had nearly 30,000 members and required them to share images of abuse to maintain good standing, according to the court documents. A private section of the forum was available only to members who shared imagery of children they abused themselves. They were known as “producers.”

Multiple police investigations over the past few years have broken up enormous dark web forums, including one known as Child’s Play that was reported to have had over a million user accounts.

The highly skilled perpetrators often taunt the authorities with their technical skills, acting boldly because they feel protected by the cover of darkness.

“People who traffic in child exploitation materials are on the cutting edge of technology,” said Susan Hennessey, a former lawyer at the National Security Agency who researches cybersecurity at the Brookings Institution.

Offenders can cover their tracks by connecting to virtual private networks, which mask their locations; deploying encryption techniques, which can hide their messages and make their hard drives impenetrable; and posting on the dark web, which is inaccessible to conventional browsers.

The anonymity offered by the sites emboldens members to post images of very young children being sexually abused, and in increasingly extreme and violent forms.

“Historically, you would never have gone to a black market shop and asked, ‘I want real hard-core with 3-year-olds,’” said Yolanda Lippert, a prosecutor in Cook County, Ill., who leads a team investigating online child abuse. “But now you can sit seemingly secure on your device searching for this stuff, trading for it.”

Exhibits in the case of the Love Zone, sealed by the court but released by a judge after a request by The Times, include screenshots showing the forum had dedicated areas where users discussed ways to remain “safe” while posting and downloading the imagery. Tips included tutorials on how to encrypt and share material without being detected by the authorities.

The offender in Ohio, a site administrator named Jason Gmoser, “went to great lengths to hide” his conduct, according to the documents. Testimony in his criminal case revealed that it would have taken the authorities “trillions of years” to crack the 41-character password he had used to encrypt the site. He eventually turned it over to investigators, and was sentenced to life in prison in 2016.

The site was run by a number of men, including Brian Davis, a worker at a child day care center in Illinois who admitted to documenting abuse of his own godson and more than a dozen other children — aged 3 months to 8 years — and sharing images of the assaults with other members. Mr. Davis made over 400 posts on the site. One image showed him orally raping a 2-year-old; another depicted a man raping an infant’s anus.

Mr. Davis, who was sentenced to 30 years in prison in 2016, said that “capturing the abuse on video was part of the excitement,” according to court records.

Some of his victims attended the court proceedings and submitted statements about their continuing struggles with the abuse.

‘Truly Terrible Things’

The surge in criminal activity on the dark web accounted for only a fraction of the 18.4 million reports of abuse last year. That number originates almost entirely with tech companies based in the United States.

The companies have known for years that their platforms were being co-opted by predators, but many of them essentially looked the other way, according to interviews and emails detailing the companies’ activities. And while many companies have made recent progress in identifying the material, they were slow to respond.

Hemanshu Nigam, a former federal prosecutor in cybercrime and child exploitation cases, said it was clear more than two decades ago that new technologies had created the biggest boon for pedophiles since the Polaroid camera.

The recent surge by tech companies in filing reports of online abuse “wouldn’t exist if they did their job then,” said Mr. Nigam, who now runs a cybersecurity consulting firm and previously held top security roles at Microsoft, Myspace and News Corporation.

Hany Farid, who worked with Microsoft to develop technology in 2009 for detecting child sexual abuse material, said tech companies had been reluctant for years to dig too deeply.

“The companies knew the house was full of roaches, and they were scared to turn the lights on,” he said. “And then when they did turn the lights on, it was worse than they thought.”

Federal law requires companies to preserve material about their reports of abuse imagery for 90 days. But given the overwhelming number of reports, it is not uncommon for requests from the authorities to reach companies too late.

“That’s a huge issue for us,” said Capt. Mike Edwards, a Seattle police commander who oversees a cybercrimes unit for the State of Washington. “You’ve got a short period of time to be able to get the data if it was preserved.”

Most tech companies have been quick to respond to urgent inquiries, but responses in other cases vary significantly. In interviews, law enforcement officials pointed to Tumblr, a blogging and social networking site with 470 million users, as one of the most problematic companies.

Capt. Mike Edwards, a police commander who oversees a cybercrime unit for the State of Washington. An agent combing a Seattle home for evidence. A digital triage area that was set up in the suspect’s kitchen.

Kholood Eid for The New York Times

Police officers in Missouri, New Jersey, Texas and Wisconsin lamented Tumblr’s poor response to requests, with one officer describing the issues as “long-term and ongoing” in an internal document.

A recent investigation in Polk County, Wis., that included an image of a man orally raping a young child stalled for over a year. The investigator retired before Tumblr responded to numerous emails requesting information.

In a 2016 Wisconsin case, Tumblr alerted a person who had uploaded explicit images that the account had been referred to the authorities, a practice that a former employee told The Times had been common for years. The tip allowed the man to destroy evidence on his electronic devices, the police said.

A spokeswoman for Verizon said that Tumblr prioritized time-sensitive cases, which delayed other responses. Since Verizon acquired the company in 2017, the spokeswoman said, its practice was not to alert users of police requests for data. Verizon recently sold Tumblr to the web development company Automattic.

The law enforcement officials also pointed to problems with Microsoft’s Bing search engine, and Snap, the parent company of the social network Snapchat.

Bing was said to regularly submit reports that lacked essential information, making investigations difficult, if not impossible. Snapchat, a platform especially popular with young people, is engineered to delete most of its content within a short period of time. According to law enforcement, when requests are made to the company, Snap often replies that it has no additional information.

A Microsoft spokesman said that the company had only limited information about offenders using the search engine, and that it was cooperating as best as it could. A Snap spokesman said the company preserved data in compliance with the law.

Data obtained through a public records request suggests Facebook’s plans to encrypt Messenger in the coming years will lead to vast numbers of images of child abuse going undetected. The data shows that WhatsApp, the company’s encrypted messaging app, submits only a small fraction of the reports Messenger does.

Facebook has long known about abusive images on its platforms, including a video of a man sexually assaulting a 6-year-old that went viral last year on Messenger. When Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, announced in March that Messenger would move to encryption, he acknowledged the risk it presented for “truly terrible things like child exploitation.”

“Encryption is a powerful tool for privacy,” he said, “but that includes the privacy of people doing bad things.”

‘Vastly Inadequate’

“In a recent case, an offender filmed himself drugging the juice boxes of neighborhood children before tricking them into drinking the mix,” said Special Agent Flint Waters, a criminal investigator for the State of Wyoming. “He then filmed himself as he sexually abused unconscious children.”

Mr. Waters, appearing before Congress in Washington, was describing what he said “we see every day.”

He went on to present a map of the United States covered with red dots, each representing a computer used to share images of child sex abuse. Fewer than two percent of the crimes would be investigated, he predicted. “We are overwhelmed, we are underfunded and we are drowning in the tidal wave of tragedy,” he said.

Mr. Waters’s testimony was delivered 12 years ago — in 2007.

The following year, Congress passed legislation that acknowledged the severity of the crisis. But then the federal government largely moved on. Some of the strongest provisions of the law were not fulfilled, and many problems went unfixed, according to interviews and government documents.

Today, Mr. Waters’s testimony offers a haunting reminder of time lost.

Annual funding for state and regional investigations was authorized at $60 million, but only about half of that is regularly approved. It has increased only slightly from 10 years ago when accounting for inflation. Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat of Connecticut who was a sponsor of the law’s reauthorization, said there was “no adequate or logical explanation and no excuse” for why more money was not allocated. Even $60 million a year, he said, would now be “vastly inadequate.”

Another cornerstone of the law, the biennial strategy reports by the Justice Department, was mostly ignored. Even the most recent of the two reports that were published, in 2010 and 2016, did not include data about some of the most pressing concerns, such as the trade in illicit imagery.

The Justice Department’s coordinator for child exploitation prevention, Ms. Harris, said she could not explain the poor record. A spokeswoman for the department, citing limited resources, said the reports would now be written every four years beginning in 2020.

When the law was reauthorized in 2012, the coordinator role was supposed to be elevated to a senior executive position with broad authority. That has not happened. “This is supposed to be the quarterback,” said Ms. Wasserman Schultz, one of the provision’s authors.

Even when the Justice Department has been publicly called out for ignoring provisions of the law, there has been little change.

In 2011, the Government Accountability Office reported that no steps had been taken to research which online offenders posed a high risk to children, and that the Justice Department had not submitted a progress assessment to Congress, both requirements of the law.

At the time, the department said it did not have enough funding to undertake the research and had no “time frame” for submitting a report. Today, the provisions remain largely unfulfilled.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which testified in favor of the 2008 law, has also struggled with demands to contain the spread of the imagery.

Founded in 1984 after the well-publicized kidnapping and murder of a 6-year-old Florida boy, Adam Walsh, the center has been closely affiliated with the federal government since the Reagan administration.

Yiota Souras and John Shehan, executives at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Milk carton ads and a photo of John and Revé Walsh, who founded the center in 1984 after their 6-year-old son was murdered.

Kholood Eid for The New York Times

But as child exploitation has grown on the internet, the center has not kept up. The technology it uses for receiving and reviewing reports of the material was created in 1998, nearly a decade before the first iPhone was released. To perform key upgrades and help modernize the system, the group has relied on donations from tech companies like Palantir and Google.

The center has said it intends to make significant improvements to its technology starting in 2020, but the problems don’t stop there. The police complain that the most urgent reports are not prioritized, or are sent to the wrong department completely.

“We’re spending a tremendous amount of time having to go through those and reanalyze them ourselves,” said Captain Edwards, the Seattle police official.

In a statement, the national center said it did its best to route reports to the correct jurisdiction.

Despite its mandate by Congress, the center is not subject to public records laws and operates with little transparency. It repeatedly denied requests from The Times for quarterly and annual reports submitted to the Justice Department, as well as for tallies of imagery reports submitted by individual tech companies.

A phone seized by a task force in Seattle. Sketches found during the raid. Agents lifting the suspect’s mattress in search of illicit material.

Kholood Eid for The New York Times

Mr. Shehan, the vice president, said such disclosures might discourage tech companies from cooperating with the center. He said the numbers could be misinterpreted.

The Times found that there was a close relationship between the center and Silicon Valley that raised questions about good governance practices. For example, the center receives both money and in-kind donations from tech companies, while employees of the same companies are sometimes members of its board. Google alone has donated nearly $4 million in the past decade, according to public testimony.

A spokeswoman for the center said it was common to expect corporations to provide financial assistance to charities. But the practice, others working in the area of child protection say, could elevate the interests of the tech companies above the children’s.

“There’s an inherent conflict in accepting money from these companies when they also sit on your board,” said Signy Arnason, who is a top executive at the equivalent organization in Canada, known as the Canadian Center for Child Protection.

This close relationship with tech companies may ultimately be in jeopardy. In 2016, a federal court held that the national center, though private, qualified legally as a government entity because it performed a number of essential government functions.

If that view gains traction, Fourth Amendment challenges about searches and seizures by the government could change how the center operates and how tech companies find and remove illegal imagery on their platforms. Under those circumstances, if they were to collaborate too closely with the center, the companies fear, they could also be viewed as government actors, not private entities, subjecting them to new legal requirements and court challenges when they police their own sites.

An Ugly Mirror

It was a sunny afternoon in July, and an unmarked police van in Salt Lake City was parked outside a pink stucco house. Garden gnomes and a heart-shaped “Welcome Friends” sign decorated the front yard.

At the back of the van, a man who lived in the house was seated in a cramped interrogation area, while officers cataloged hard drives and sifted through web histories from his computers.

The man had shared sexually explicit videos online, the police said, including one of a 10-year-old boy being “orally sodomized” by a man, and another of a man forcing two young boys to engage in anal intercourse.

“The sad thing is that’s pretty tame compared to what we’ve seen,” said Chief Jessica Farnsworth, an official with the Utah attorney general’s office who led a raid of the house. The victims have not been identified or rescued.

Investigators in Salt Lake City searching a home for abuse content. Confiscated electronic material in a mobile forensics lab. Jessica Farnsworth, an official with the Utah attorney general’s office who oversaw the operation.

Kholood Eid for The New York Times

The year was barely half over, and Chief Farnsworth’s team had already conducted about 150 such raids across Utah. The specially trained group, one of 61 nationwide, coordinates state and regional responses to internet crimes against children.

The Utah group expects to arrest nearly twice as many people this year as last year for crimes related to child sexual abuse material, but federal funding has not kept pace with the surge. Funding for the 61 task forces from 2010 to 2018 remained relatively flat, federal data shows, while the number of leads referred to them increased by more than 400 percent.

Much of the federal money goes toward training new staff members because the cases take a heavy emotional and psychological toll on investigators, resulting in constant turnover.

“I thought that I was in the underbelly of society — until I came here,” said Ms. Lippert, the prosecutor with the task force in Illinois, who had worked for years at a busy Chicago courthouse.

While any child at imminent risk remains a priority, the volume of work has also forced the task forces to make difficult choices. Some have focused on the youngest and most vulnerable victims, while others have cut back on undercover operations, including infiltrating chat rooms and online forums.

“I think some of the bigger fish who are out there are staying out there,” Ms. Lippert said.

The internet is well known as a haven for hate speech, terrorism-related content and criminal activity, all of which have raised alarms and spurred public debate and action.

But the problem of child sexual abuse imagery faces a particular hurdle: It gets scant attention because few people want to confront the enormity and horror of the content, or they wrongly dismiss it as primarily teenagers sending inappropriate selfies.

Some state lawmakers, judges and members of Congress have refused to discuss the problem in detail, or have avoided attending meetings and hearings when it was on the agenda, according to interviews with law enforcement officials and victims.

Steven J. Grocki, who leads a group of policy experts and lawyers at the child exploitation section of the Justice Department, said the reluctance to address the issue went beyond elected officials and was a societal problem. “They turn away from it because it’s too ugly of a mirror,” he said.

Yet the material is everywhere, and ever more available.

“I think that people were always there, but the access is so easy,” said Lt. John Pizzuro, a task force commander in New Jersey. “You got nine million people in the state of New Jersey. Based upon statistics, we can probably arrest 400,000 people.”

Common language about the abuse can also minimize the harm in people’s minds. While the imagery is often defined as “child pornography” in state and federal laws, experts prefer terms like child sexual abuse imagery or child exploitation material to underscore the seriousness of the crimes and to avoid conflating it with adult pornography, which is legal for people over 18.

“Each and every image is a depiction of a crime in progress,” said Sgt. Jeff Swanson, a task force commander in Kansas. “The violence inflicted on these kids is unimaginable.”