“The silent epidemic of America’s problem with guns”, BBC News

By Joel Gunter, Long Read, 6 February 2020

Mass shootings dominate the national conversation on gun control, but two thirds of gun deaths are suicides. How do you solve a problem hardly anyone talks about?

Image copyrightDON BARTLETTI/BBC

Image copyrightDON BARTLETTI/BBC

The night Brayden died was a cold, clear night in Helena, in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Montana. Snow had fallen lightly on the city and lay drifted around the houses. Brayden was in his bedroom with his mother Melissa, watching reruns of his favourite TV sketch show. Across town, Brayden’s best friend Kase was with his own mother at the home of a family friend.

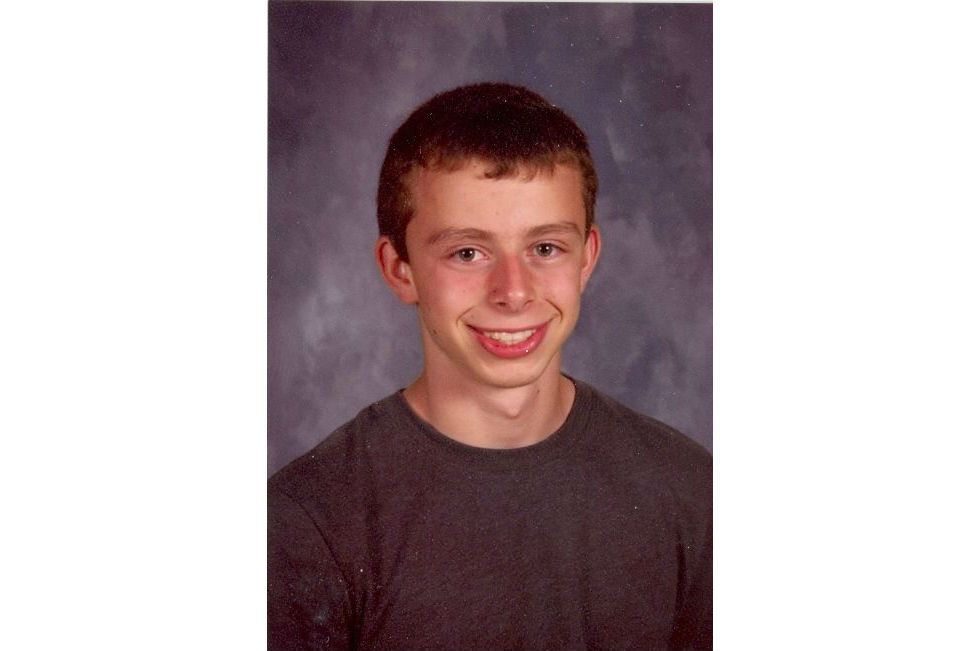

By that point, in early February 2016, Brayden Schaeffer and Kase Dietrich had been friends for nearly half their lives. They met aged nine, when Brayden joined late at the local high school in Helena and needed someone to show him around. Brayden was a bright-eyed boy with a wide, toothy smile and a fondness for practical jokes. Kase was a quiet boy with a shy manner. He was drawn to Brayden’s easy confidence.

The boys began hanging out every day, at school and after school, growing closer with time. Seven years went by like that, until, aged 16, Brayden and Kase were living a few miles apart in Helena, filling long summer days with each other’s company — playing basketball, swimming at the lake, or driving aimlessly in Brayden’s black ’91 Chevy pickup.

On a rare day they didn’t see each other they texted, exchanging hundreds of messages over the years. That night in February was no different. Kase texted to say he’d left a pair of jeans at Brayden’s house; Brayden replied saying he hadn’t finished his homework. Kase pulled his friend up on the homework.

“Dude, you need to do that,” he wrote. “Don’t fail school”.

“I won’t dude,” Brayden wrote back. “Okay, just making sure,” Kase replied.

It mattered to Kase that Brayden kept it together. Kase’s own future felt uncertain — his father was in prison and his mother had moved him from home to home, always fighting to make rent. He had dropped out of school the summer before, aged 15, and was working in a taco restaurant. Brayden was like a brother to him; the two boys looked out for one another.

Kase’s phone lit up with another text. “Yo dude,” it said. “You’re an awesome friend dude.”

Kase sensed a change in tone. “Thanks bud, what’s going on?” he replied.

“Dude I don’t feel it anymore,” Brayden wrote back. “I don’t feel like continuing.”

Kase had never suspected his friend was suicidal. “He was just this happy-go-lucky guy,” Kase told me. “He played sports, he helped his friends. He brought other people up when they were down. He was just a great guy.”

But sitting in his room that night in February, Kase began to worry. He texted back: “Do I have to come over there bro?”

At Brayden’s house, Melissa had grown tired and got up from the TV. She told Brayden she loved him and told him not to stay up late, then she went to bed. Alone in his room, Brayden sent Kase a string of increasingly hopeless messages. “Dude I’m just sitting with my dog now thinking,” he wrote. “Like, I have nothing with me now but I don’t know”.

Kase replied, “Do you need me bro?”

Then Brayden told his friend not to come to his house, “no matter what”.

“Don’t come over if I stop responding,” he wrote, “call the cops dude.”

Kase bounded out of his room and down the stairs and grabbed his mother’s car keys. “Brayden needs me now!” he shouted as he ran out the door.

At Brayden’s, Melissa heard her son get up. She called out to him from her room, and he said that he was just getting a movie, and he loved her and he would see her tomorrow.

As Kase raced the few miles across town, his phone flashed in his pocket with a final message, one that he wouldn’t see until after he reached the house, until it was too late.

“Yo dude, call me plz.”

He is still bewildered by the speed with which he lost his friend. “It was just an ordinary conversation on an ordinary night,” he said. “Suddenly it went from light to dark.”

Suicide rates in the US have risen dramatically over the past two decades, stubbornly defying prevention efforts and morphing into a nationwide public health crisis. Brayden was one of nearly 45,000 Americans who killed themselves in 2016. Even at a conservative estimate, that was twice the number of homicides that year. According to data published last week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the national suicide rate rose 35% between 1999 and 2018, increasing in all states. In Montana, where Brayden lived, it rose 38% in two decades and people killed themselves at a rate that surpassed any other state in America.

And the increases are most acute in America’s adolescent population, outstripping all other age groups. According to the CDC, the rate of teenagers and young adults taking their lives rose 47% in two decades.

The CDC points to a wide variety of driving forces behind suicide: social and geographical isolation, financial hardship, drug and alcohol dependency and mental health problems. But it also highlights a common factor in the majority of American suicides: a gun.

Most people who kill themselves in the US use a gun. Brayden used a gun. Suicide is the silent epidemic of America’s problem with firearms — it accounts for roughly two-thirds of all gun deaths, while the national conversation around gun control is dominated by mass shootings, which account for less than 1%. In 2018, on average, 67 people died by firearm suicide every day, a figure that has risen every single year since 2006.

Part of the problem with guns is that they are by far the most fatal means. There are three statistics which together paint a stark picture of the role of firearms in American suicides:about 85% of people who use a gun will die; about 95% of people who use another means will survive; and about 90% of those who survive will not go on to try again.

“Too many people think that if you want to take your own life you will, and the means don’t matter. But a gun in the home increases the chance of suicide probably threefold,” said David Hemenway, the director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center (HICRC) and one of the country’s leading suicide researchers.

“If you were to ask what’s the one thing we really know from suicide research in the US, that would be it,” he said.

Image copyrightLOUISE JOHNS/BBC

Image copyrightLOUISE JOHNS/BBC

Suicide prevention efforts have historically focused on what Hemenway called “the why” — social, financial, and mental health triggers. He and his fellow researchers at the HICRC in Boston would like to shift some of that focus to a more easily modifiable part of the phenomenon: the means people use, “the how”.

“It is natural to focus on the why, to try and understand how someone got to that point,” said Catherine Barber, a colleague of Hemenway and associate director at the HICRC. “But at some point you have to stop and think about what’s a more actionable approach to saving lives,” she said, “and that’s the how.”

Guns — the most prevalent ‘how’ in American suicides — take away time. They are fast and lethally efficient and leave little room for a change of heart or a life-saving intervention. And yet study after study shows that suicide is a dramatically impulsive act.

In a 2009 study, 48% of people who made a near-lethal attempt on their life said they started thinking about suicide less than 10 minutes before the act. Another study from 2001 showed the same percentage deliberated for less than 20 minutes. Researchers say putting even a short amount of time, or a small obstacle, between people and the means to kill themselves can prevent a death.

“It’s actually pretty darn hard to take your own life, because your body rejects it or your mind struggles against it,” Barber said. “Most suicide methods give you that opportunity, because they take time. And sometimes just a small amount of time is enough.”

If you ask Brayden’s dad Steve, he’ll tell you his son only needed a minute.

“That’s what I always say, ‘He just needed a minute’. And the more you talk about this issue the more you find people who were going to do it and didn’t, because they got that minute.”

Steve Schaeffer still lives in Helena, where he has taken on an active role in raising awareness around suicide and mental health. One wall of his apartment is adorned with framed memories of his son — photographs, childhood drawings, a basketball jersey. Brayden’s name is embroidered on his motorbike vest, over his heart. The night Brayden died Steve was in Sacramento, fast asleep in a hotel room after a sales job that day. His phone — on silent but programmed to ring after repeated calls from the same number — eventually woke him, and he heard down the line from an old Helena High classmate-turned-police officer that his son was dead.

Steve still dwells on the final message his son sent to Kase that night.

“Yo dude, call me plz.”

It was Brayden looking for that minute, Steve said.

“There are lots of ways to kill yourself but a gun is the most instantaneous. It’s the easiest, it’s the quickest.

“I’m not saying get rid of guns, I’m not saying get rid of rights, but we have simply got to have better laws.”

History tells us that reducing access to certain means of suicide can have a dramatic effect on suicide rates. In the early 20th Century, the UK began heating domestic ovens with coal gas, which contained lethal levels of carbon monoxide. Suicide rates spiked, particularly among women, and by the 1950s more than half of all suicides in the UK — about the same proportion as firearm suicides in the US today — involved a coal gas oven. Then in 1958 the government began, incidentally, to replace coal gas with a cleaner natural gas which was virtually free of carbon monoxide, and by the early 1970s gas oven suicides fell to zero and the overall national suicide rate fell by a third. The so-called “coal gas story” became a touchstone for suicide prevention experts worldwide.

There are other examples. In the early 1990s, Sri Lanka had one of the highest suicide rates in the world, driven by the ready availability of toxic pesticides. Two laws passed in 1995 and 1998 restricted access to a deadly class of pesticides and by 2005 the suicide rate had fallen by half.

In Switzerland, army reforms in 2003 halved the number of soldiers and the knock-on reduction in the availability of firearms brought about a sharp reduction in suicides among men. Similarly in Israel, in 2006, the army prohibited younger soldiers from taking their service weapons home at the weekend and the measure led to 40% fall in suicides. And legislation passed in the UK in 1998 outlawed the sale of painkillers in bottles, meaning anyone wanting a large quantity had to push them out from blister packs one by one. That seemingly small obstacle had a significant effect — painkiller overdoses fell by 43% over the next decade and overdose-related liver transplants by 61%.

Similar reductions have been observed in the US after the installation of access barriers that prevent people jumping from bridges, and studies tend to show little or no “substitution” effect — ie increases in the number of suicides at nearby bridges. In San Francisco, where dozens of people die every year after jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge, a five-year, $76 million metal suicide barrier, paid for by the state, is scheduled for completion by 2023.

But access barriers to guns are a different story. The National Rifle Association (NRA), the nation’s leading gun lobby group, exerts an enduring hold on the Republican Party and fiercely resists nearly all legislation that infringes on ready access to firearms. It denies that stricter gun laws correlate with lower suicide rates — its news arm said recently that including suicides in the annual gun death toll amounted to “fake news”. The NRA did not respond to a request to comment for this story.

“Anything that puts a barrier between a potential customer and a gun gets resistance from the industry,” said Paul Nestadt, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the John Hopkins School of Medicine. “And yet study after study shows that any regulation that limits access to firearms decreases suicide rates.”

Image copyrightLOUISE JOHNS/BBC

Image copyrightLOUISE JOHNS/BBC

The simplest barrier to a gun is a lock. The gun Brayden used to kill himself was behind a lock, in a wooden cabinet, but Brayden knew where to find the key and the ammunition was stored with the gun. Many guns are even less safe than that. According to a 2015 national study, about two in 10 gun-owning households with children store at least one weapon in the least safe manner – loaded and unlocked. That means that about 7% of US children — roughly 4.6 million — live within reach of a loaded gun.

There are no federal laws and few state laws requiring safe storage of guns, and no federal standards for firearm locks. Only seven of the 50 states have laws requiring the safe storage of guns in the home, and they are nearly impossible to enforce without going door-to-door with a warrant, which is, as Nestadt pointed out, “frankly, un-American”.

There are other options. In the wake of two mass shootings in Texas and Ohio in August, which killed 29 people in 24 hours and briefly shook the nation from a business-as-usual approach to gun violence, so-called “red-flag” laws emerged as a rare point of agreement across the political aisle.

Red flag laws — properly known as extreme risk protection orders, or ERPOs — allow family members to petition a court to temporarily remove a person’s access to firearms if they pose a threat to themselves or others. It is telling that it took two mass shootings, and not decades of rising firearm suicide rates, to bring ERPOs into the public consciousness, but the evidence suggests they are as effective a suicide prevention tool as the US can realistically hope for. ERPOs were associated with a 7.5% reduction in firearm suicides in Indiana and a 14% reduction in Connecticut, where the proportion of gun-removal subjects receiving outpatient mental health treatment doubled within a year of the law being introduced.

Related stories

- ‘I accidentally shot dead my little sister’

- I was shot. Now I owe tens of thousands

- Coping with our daughter’s new face

A small wave of states adopted ERPO laws in the wake of the school shooting in Parkland, Florida in February 2018, but there are still only 17 states with some form of the regulation on the books. And only two states, Maryland and Hawaii, plus the District of Columbia, allow doctors — often the first to spot signs of mental health crisis in children and adolescents — to petition for one.

Public health researchers can reel off a list of similar laws and protections which they say would help reduce gun suicides without significantly infringing the rights of gun owners:mandatory waiting periods; universal background checks; safe storage; and closing loopholes like the one in Maryland that allows anyone to buy a rifle or shotgun from a private seller without a background check, and exempts those so-called ‘long guns’ from the minimum age requirements of handguns (nearly half of the teenagers who killed themselves in Maryland between 2003 and 2018 used a long gun).

Among the most effective might be permit-to-purchase laws, which exist in some form in about 13 states and require prospective gun purchasers to apply for a permit, in person, at a law enforcement office. Anyone granted a permit can then purchase guns for the following five years without undergoing repeated background checks, as they would have to otherwise. But for those buying a gun impulsively, they create a temporary barrier. Researchers at John Hopkins estimated that Connecticut’s permit-to-purchase law, introduced in 1995, was associated with a 15.4% reduction in firearm suicides, while Missouri’s removal of its permit-to-purchase law in 2007 was associated with a 16.1% increase in firearm suicides.

“When these kinds of policies are put into place in a thoughtful way, they work,” said Nestadt. “The problem is we’re not putting nearly enough of them into place and when we do they often end up weakened. The opposition is very, very powerful.”

With little chance of significant legislative changes, some public health officials now see the best hope for reducing gun suicides not in Washington DC, or in wood-panelled courtrooms or state legislatures, but in an altogether less likely place: gun shops.

In a few states, unlikely coalitions of public health researchers and gun enthusiasts have formed with the shared goal of raising awareness. The first such coalition was born nearly a decade ago when Ralph Demicco, the owner of a large gun shop in the small town of Hooksett, New Hampshire, got a call from a local public health researcher after the local coroner saw that three people had killed themselves in the space of six days shortly after buying a gun from his store. “I was dumbfounded,” Demicco told me. “I couldn’t believe it.”

Demicco watched and re-watched CCTV tapes of the sales. He had believed he was running a socially responsible gun shop, one that even boasted of an unofficial motto, “firearms for the responsible”, where staff applied due diligence to every sale and were able to identify vulnerable people or people in a crisis. But when he watched the tapes he saw three normal looking sales. “I saw nothing out of the ordinary,” he said, “nothing.”

He agreed to join forces with the researcher who’d called him, Dr Elaine Frank, and together they created the Gun Shop Project. With no state backing and barely any money, they produced display posters and cards with safe gun storage advice and contact details for support groups, and posted them to about 70 gun shops in New Hampshire, where more than 85% of gun deaths are suicides.

Between the project and its goal lay years of deep-seated mistrust. Some shop owners said it was just another way to demonise guns. Others said it would be bad for business. But six months after their mailout, Frank and Demicco personally visited every shop on the list, unannounced, and found their booklets and posters displayed in about half.

“We considered that a pretty big success, getting some of the gun store owners to trust the public health people,” Demicco said. “I had never seen that before.”

Word of the project spread to other states. In Colorado, the state’s small suicide prevention team was looking for a way to reduce a high rate of firearm suicides in a state heavily resistant to gun laws. Jarrod Hindman, who had directed Colorado’s suicide prevention efforts for a decade, put together a pitch for funding to replicate the Gun Shop Project. A pilot was approved, then put on hold by higher powers for fear it might turn off voters ahead of a gubernatorial election, then eventually given the go-ahead again after a high-profile school shooting turned suicide.

Image copyrightANADOLU

Image copyrightANADOLU

Concerned that a state-backed initiative might rile people in the gun community — which has traditionally overlapped with those wary of interventions by state and federal government — Hindman and his team disguised their hand in the project.

“We were very deliberate to not make it a state initiative, we didn’t put any state logos on any of the messaging,” he said. “We distributed all the materials through local partners at county level and encouraged them to put their logos on it, so it looked to local people like a local initiative.”

The project was rolled out to five mostly rural counties on the Western Slope of the Rocky Mountains — about 50 gun shops in all. The kinds of people approached to help roll it out were those who could walk into a gun shop without seeming out of place. In Montrose, on the Western Slope, the choice was the local police commander, Keith Caddy, who was born in the town, raised on a ranch and became an NRA member and a firm believer in the right to bear arms.

“I knew all the gun store owners personally,” Caddy told me. “These are people I can sit down and talk to one on one, comfortably, instead of them just listening to a spiel from a state or federal agency.”

And it most cases it worked, he said. Gun shop and range owners in rural western Colorado engaged with a public health initiative that might otherwise have met with resistance.

“I’ve known Keith for ever,” said Steve Smith, the owner of Gun Depot in Montrose, where suicide prevention advice can now be found on the store’s countertops. “When you get someone like Keith coming in and talking to me, heck, I’m going to listen because, well hell we went to high school together.”

Some of those Caddy approached responded with their own personal experiences. Keith Carey, a softly-spoken gunsmith who repairs rifles, handguns and horns — the musical type — from a small one-man workshop next to his Montrose home, had lost his daughter to an intentional overdose in 2009.

“With my daughter, it brought it extremely close at hand,” Carey said. “Suicide, by any means, is a truly horrible and debilitating thing for family members and friends. But guns, particularly in the west, are very prevalent. We’re very pro-gun, pro-second amendment, pro-USA. And guns are the most expedient ways of taking one’s life.”

Carey now displays the suicide prevention pamphlets Caddy gave him prominently in his small shop. “Some people take the information,” he said. “The majority will look at it and not take it. I keep it on the counter, it’s there every day. Every new customer sees it. I feel I have an obligation to do that.”

Any suicide prevention initiative would have his support, he said, short of putting any new gun laws in place.

Image copyrightAP

Image copyrightAP

According to Hindman, the state suicide prevention coordinator, the initial Colorado pilot saw about the same success rate as one in New Hampshire — a little over 50% of the shops agreed to display the materials. With a small amount of renewed funding, they spread the project out from the Western Slope to other parts of the state.

Jacquelyn Clark, the owner of Bristlecone Shooting in the capital Denver, not only took on the project’s display materials she added her own innovations. She changed the rules at Bristlecone to prevent new customers renting a firearm to shoot on the shop’s range if they arrived alone. (A number of people in the US have killed themselves at gun ranges with rented guns. “It happens more often than people talk about,” Clark said.)

She introduced suicide awareness and safe storage advice to her monthly ladies night, and she began offering — for the price of a background check — to hold on to guns for anyone concerned about a family member or themselves. It is now the “11th Commandment” of the shop’s printed gun safety guidelines: “Consider temporary off-site storage if a family member may be suicidal.”

Every once in a while Clark’s staff got a negative reaction to the new range policy or the posters, she said, but more often they heard a personal story about suicide. “Sure, we might lose a little bit of business, but we’d rather lose one or two customers than have a tragedy,” she said.

In Brayden’s home state of Montana, which has the highest suicide rate in the nation and the sixth highest rate of firearms ownership, the Gun Shop Project is yet to make any inroads. “We have a little bit of a different attitude in Montana around firearms,” said Karl Rosston, the state’s suicide prevention co-ordinator. “And that’s an understatement.”

Rosston and his team produced a TV ad to promote suicide awareness around guns, but they were fighting against a “cowboy up mentality”, he said, “where you keep to your own and no-one tells you what to do.”

“That mentality creates a stigma, and stigma is what stops people from safely storing firearms, from locking up medications, from seeking mental health services. It’s incredibly strong, it’s culturally ingrained, and it’s been this way for more than a hundred years,” he said.

Whether the Gun Shop Project will have a statistical effect on gun suicides is impossible to determine at this stage, there isn’t enough money behind the project in any state to do the kind of analysis necessary. And data collection would be tough, said Mike Anestis, a leading suicide researcher. “You would have to track who was coming in and out of gun stores and there’s a huge barrier there. Paranoia isn’t the right word, but there’s a concern about outsiders creating a registry of gun owners. The data you would need to evaluate these approaches is real hard to get at.”

Ralph Demicco, the gun shop owner who took the call that gave life to the original project, admitted he had “serious questions as to how effective the whole programme was going to be”. But he is spending his retirement years trying to roll it out to other states. “I am hopeful,” he said.

Riley’s, his New Hampshire gun store, closed in November, but the small town of Hooksett has four other gun stores, and provided you can pass an instant background check you can still walk into one and walk out minutes later with a gun.

Firearms are not the only factor in American suicides; far from it, suicide is complex and varied and has — in the language of public health — many risk factors. A gun is one. But guns are a “modifiable risk factor”. Like coal gas, paracetamol packaging, and pesticides, guns can be removed from the equation.

The night Brayden died, his mother Melissa gave the shotgun he used to the police and told them not to bring it back. Later, she wished someone had warned her about storing a firearm in her home. She wished she could go home and separate the bullets from the gun or hide the key that opened the wooden cabinet.

“I’ve heard since Brayden died that if you have a gun in the house you should keep the bullets separately. I wish sometimes someone had told me that before,” she said. “But you know, even if someone had reached out to me before, I might have thought I didn’t need to do it. Because my son would never do that.”

She remembered waiting for Brayden’s toxicology report. She had hated discovering, in the months before he died, that he was smoking cannabis, but after his death she found herself hoping the report would show he was high when he died. When it came back negative, she hoped she would find out he had fallen into debt. She craved something that would make sense of what happened, that would explain to her why her son would kill himself moments after he told her he loved her.

Image copyrightLOUISE JOHNS/BBC

Image copyrightLOUISE JOHNS/BBC

A little while later, Melissa put her house on the market and left the old neighbourhood for good. She hasn’t picked up a gun since, breaking an old target shooting hobby. But it wasn’t until Mother’s Day two years after Brayden died that she could bear the pain of visiting his grave, a short drive from her new house in Helena. “Brayden was a lovely soul,” she told me afterwards. “He and I were just really good friends.”

Neither Melissa, Steve, nor Kase believe in banning guns, but like six in 10 Americans they believe in the need for some stricter gun laws.

“This is where gun people go sideways — they say everyone’s coming to take all the guns away,” said Steve. “But it’s not about that, it’s about safety, it’s about keeping your guns and your bullets separate. Because it only takes one time, and you’ll be sorry you didn’t.”

Steve now works with the East Helena Suicide Prevention and Awareness Coalition, a group founded by Brayden’s cousin Tova in the wake of Brayden’s death. In April, Tova will oversee the fourth annual Out of Darkness awareness walk as chair of the group. Organisers will hand out beads in nine different colours to signify different personal connections to suicide and mental illness: red for the loss of a spouse; gold for a parent; white for a child. Tova will wear a purple bead for the loss of her cousin, Steve white for the loss of his son. He hopes the walks will encourage people to overcome the stigma around mental health and talk about their problems before it’s too late. But the organisers also hand out free trigger locks, to encourage people to secure their guns. “What else are we supposed to do?” he said.

Kase dealt with Brayden’s death in part by signing up to join the Marines and leaving Montana for a military base 1,200 miles away in Oceanside, California. He left behind Brayden’s truck — a black ’91 Chevy pickup that Steve had given him after Brayden died — and the truck stayed in Helena with a broken transmission, gathering dust. After a couple of years in California, Kase sent some money up to a repair shop in Helena to have the truck fixed up, and two weeks later he made his first trip back home since Brayden died, to collect it. In the Chevy’s cab, Brayden’s old air freshener cards hung from the mirror alongside Kase’s high school graduation tassel.

“Having the truck again, it was like having a piece of him back,” Kase said. “Sitting in it was like hanging out with him again.”

Image copyrightDON BARTLETTI/BBC

Image copyrightDON BARTLETTI/BBC

On his second to last day in Helena, Kase drove the Chevy up to the Resurrection Cemetery to visit Brayden’s grave for the first time. The headstone he found was a tall, curved slab of gray marble with an engraved photograph of Brayden and an inscription that read, “Promise me you’ll think of me every time you look up in the sky and see a star.” Brayden smiled brightly in the photograph — a school picture taken not long before he died. Kase sat silently in front of the stone for half an hour, wondering what he was supposed to feel. Then he drove home to pack up his things.

Early the next morning, he climbed into the driver’s seat of Brayden’s truck, turned the key in the ignition, and pulled on to the road for the 17-hour drive back to California. And all the way, on and off, he thought about his friend.

If you want to talk to someone about the issues raised in this piece, you can call the USNational Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

You can call the UK Samaritans Helpline on 116 123 or visit samaritans.org.