Battle of Salamis, 480 BC, BBC News, Long Read, 17 Feb 2020

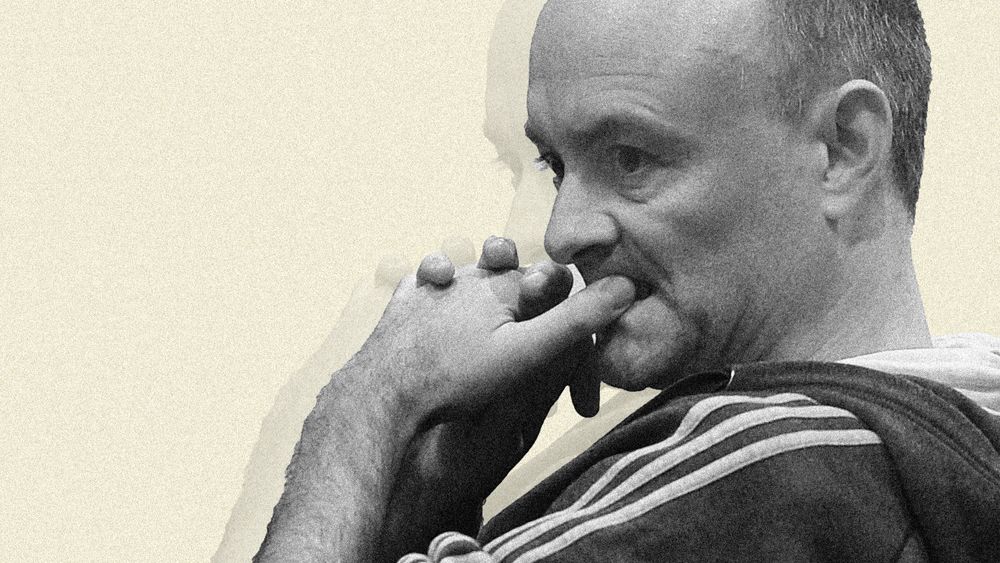

It may well be that one of least well-known names of a person who has had an enormous global impact in modern times is Dominic Cummings.

No Brexit without him.

And no Boris Johnson in a commanding position as prime minister of the UK to finish Brexit without him.

The impact on global politics and society is a bit difficult to overstate, as we’ve pointed out since the Leave vote won narrowly over the Remain vote over three and a half years ago.

The relationship between the horror in Syria (descending again to new lows as we write), the re-ordering of the global order as a result of the response of the US and others, the refugee crisis originating there and elsewhere, and the political impact of this, has been revisited often by us.

As has the relationship of all the above to inequality and lack of basic needs in a feedback loop from hell that has changed the political and social landscape from the UK to Europe to the US and around the world.

Brexit–the UK leaving the European Union with a bare majority approving a generally-worded referendum with no specifics in 2016–was in many ways the vanguard of a global reaction against a globalism that while inevitable, was and is unsustainable as long as it makes the rich richer and leaves the rest behind in varying degrees. The nationalistic retreat by the UK from the EU has been mimicked in the US and around the world, and while the tribalist reactions along the path to recognizing the one-world reality would always be predictable, the convulsions have been underpinned by the same thing throughout history, the gulf between haves and have-nots when it becomes wider rather than more equal.

Cummings hatched the strategy of finding the alienated economically dispossessed voters who were off the radar screen and targeting them with digital media in the Brexit vote. And he hatched the strategy of targeting them again in the UK election that for the first time delivered Labour strongholds to the Conservatives and Johnson.

A majority in the UK–small but more than had voted Leave in 2016–favored staying in the EU in recent polls, even though Johnson and the Conservatives then won a historic victory with the slogan “Get Brexit Done”. The slogan was Cummings’ idea.

The concept was simple–everyone was exhausted by the impasse and the seeming political impossibility of creating another referendum, and Labour under Corbyn on this issue was squishy and feckless at best (after making real advances against a seemingly even more feckless Teresa May at a different moment only two years before in a continuously shifting and polarized terrain). The system also divided the popular votes in ways that didn’t add up to a parliamentary majority for what the majority wanted on Brexit–but again, exhaustion and no effective political leadership.

In some ways the most shocking and telling result of the election was the degree to which the Conservatives took working class constituencies away from Labour. This was what Cummings sought. And he, and apparently Johnson plan to pour enormous resources into these constituencies–to in effect redistribute wealth to the have-nots. Time will tell if it actually happens.

But just as Johnson ran a campaign on the idea that he was the better choice to make sure the National Health Service–that most socialist of programs–was fully funded, he also stole the thunder of Labour on who would most help those left-behind by the elites.

All this remains (excuse the pun) to play out, but the points are that inequality creates the instability in which disruption, directed and misdirected, will occur, and that traditional left and right and the make-up of political parties can change enormously in addressing it. Right after Johnson’s historic conservative sweep in the UK, Sinn Féin, the party of the left in Ireland, had the best showing in popular vote–both in effect fueled by the same underlying issue of inequality.

Cummings has changed so many things on so many levels, no one piece will cover it. But the long read on his influence in the BBC News last week by Newsnight’s political editor Nicholas Watt is a good start.

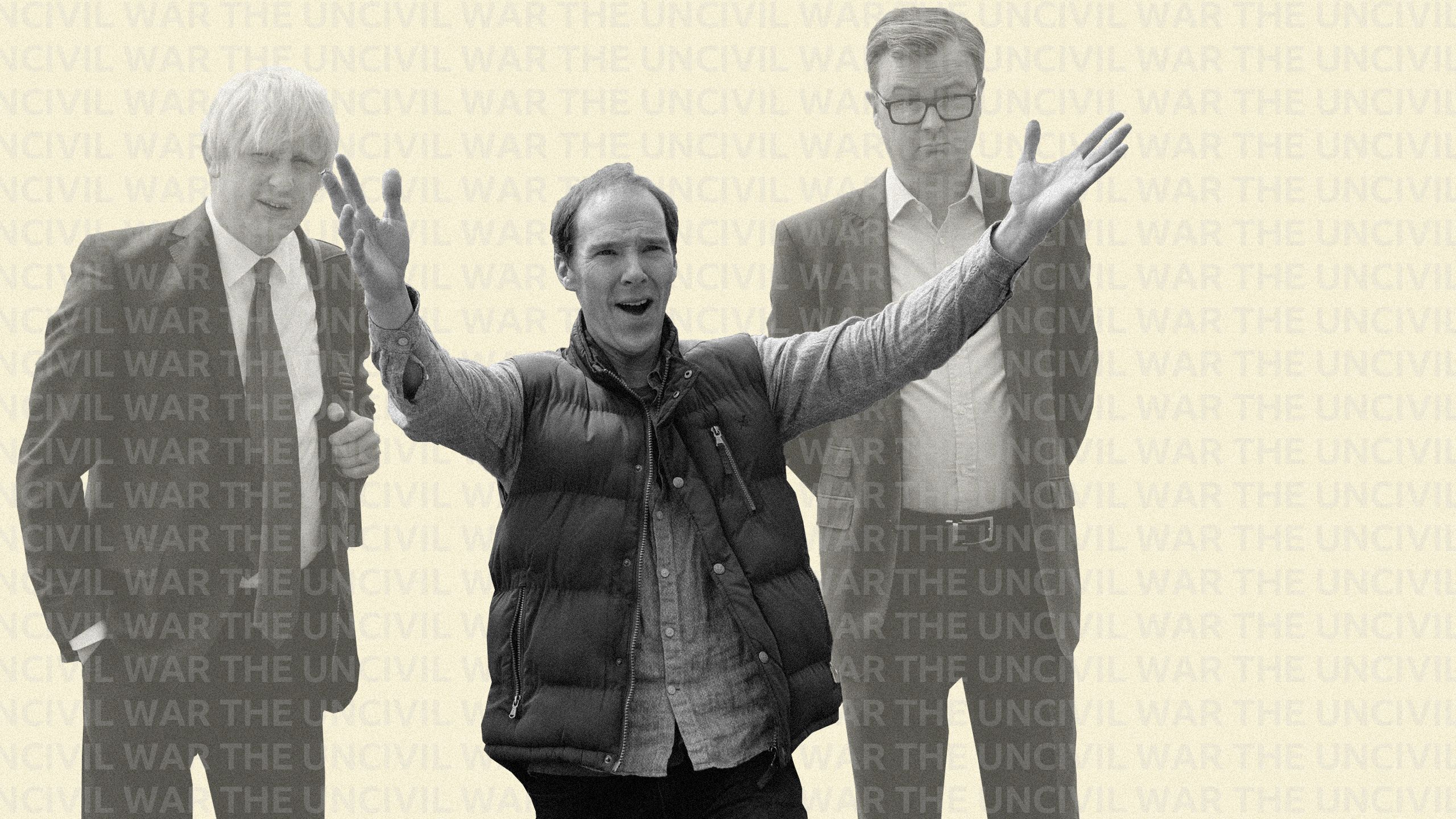

It also mentions the Channel Four drama, Brexit: The Uncivil War, which was shown on HBO in the US as Brexit.

Cummings was played by Benedict Cumberbatch, who was brilliant as usual, and particularly so in this part. We strongly recommend viewing it. Much of the focus was on the revolutionary manner in which digital media was used–the fallout from which in the US and around the world has been of great concern ever since. But the underlying reasons of social inequality that made this possible is also shown, which of course fed the capacity to pit have-not groups against each other, hence the anti-refugee sentiment to exploit, among other things.

Cummings wasn’t in agreement with the approach of some of his allies in the Leave campaign, and his fundamental positions or strategies have always been anti-elitist, disruptive and revolutionary. In an odd way, he reminds of the iconic Che Guevarra, who in his youth in The Motorcycle Diaries (a movie not to be missed), is an inspiring empathetic idealist who sees the status quo for the oppressor it is, then appears to eventually be driven mad by the inequities, to the point of being willing to light the match that obliterates the planet in the Cuban Missile Crisis. Cummings has not done anything comparable related to the latter, but the willingness to use tactics and be associated with what he has, has lit matches to processes that are yet to be fully measured in their impact.

The BBC piece notes:

In his blogs, Cummings cites Thucydides writing of the Battle of Salamis in 480BC: “A man harms his foes thus: those things they most dread he discovers, carefully investigates, then inflicts upon them.’ Cummings remembered this lesson in the Brexit referendum.”

…One admirer at the time said that…Cummings was heavily influenced by Lenin, who famously argued that “you cannot make a revolution in white gloves”.

“Dom is a much more successful Leninist than any of the Leninists around Corbyn,” the friend says.

Cummings rather enjoys being compared to the father of the Russian revolution. But when he heard that someone close to Cameron had compared him to Mao, he threw back a quote from the founder of the People’s Republic of China at the Downing Street dilettantes. “A revolution is not a dinner party, comrade,” he would say.

…But behind the part-gruff, part-mannered exterior lurks a rare beast in British politics: a thinker who has read widely, is frustrated with current government structures and who believes that it is only by lobbing proverbial hand grenades into established institutions that anyone can deliver lasting change.

As a public schoolboy who went to Oxford and tends to hang round in aristocratic circles, Dominic Cummings is an unlikely champion of the dispossessed.

But the defining mission of his career is to articulate and channel the frustration of voters who feel alienated by what has been described as the Westminster elite. Identifying the anger of these voters helped him deliver the three unequivocal successes of his career – winning a 2004 referendum, which killed off the then Labour government’s plans for a political assembly in the north-east of England; winning the 2016 Brexit referendum; and finally helping to mastermind last December’s election win as voters in Labour’s “Red Wall” in the north of England defected to the Tories.

Cummings believes the fate of Boris Johnson’s government will depend on whether it delivers for these “left behind” towns where voters feel little connection with the often more affluent cities.

Here’s the article:

“Dominic Cummings and the battle for Downing Street”

By Nicholas Watt, Long Read, BBC News, 17 Feb 2020

With some of the finest English sparkling wine in full flow, Boris Johnson placed his arms around Dominic Cummings.

In the shadow of the grand portraits that dominate the Downing Street State Room, the prime minister was showing his high regard for the man who had played an instrumental role in delivering Brexit.

Pausing for a moment at the Downing Street Brexit night party on 31 January, Johnson hailed Cummings as a “genius”.

“It was very, very clear that the only person who was singled out for praise and attention was Dom,” one participant recalls. “A couple of other people were mentioned but this was the genius guy who delivered everything. For now the person Boris will turn to more than anyone else is Dom.”

Cummings welled up, not because he was moved by the prime ministerial attention. The man whom many see as the dishevelled rule-breaker-in-chief is rarely left in awe by authority. He struggled for words – overcome with emotion that his Brexit dream was actually happening, nearly four years after he helped mastermind the successful Vote Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum.

The man who had helped deliver the vote had gone on, in the prime minister’s eyes, to save the project. It was Cummings who was invited to become Johnson’s chief strategist after his election as Conservative leader last July. “Get Brexit done” was the sound bite of the subsequent general election. Cummings was credited with it.

But within days of that prime ministerial hug, there were questions. Was Cummings losing influence? When Johnson backed HS2, the high-speed rail scheme which came with a significant dollop of Cummings scepticism, commentators suggested the strategic adviser had lost big. A significant re-organisation of the departments of government which Cummings backed also appeared to have been put not so much on the back burner as taken off the cooker altogether. Was Svengali becoming SAINO? Strategic Adviser in Name Only.

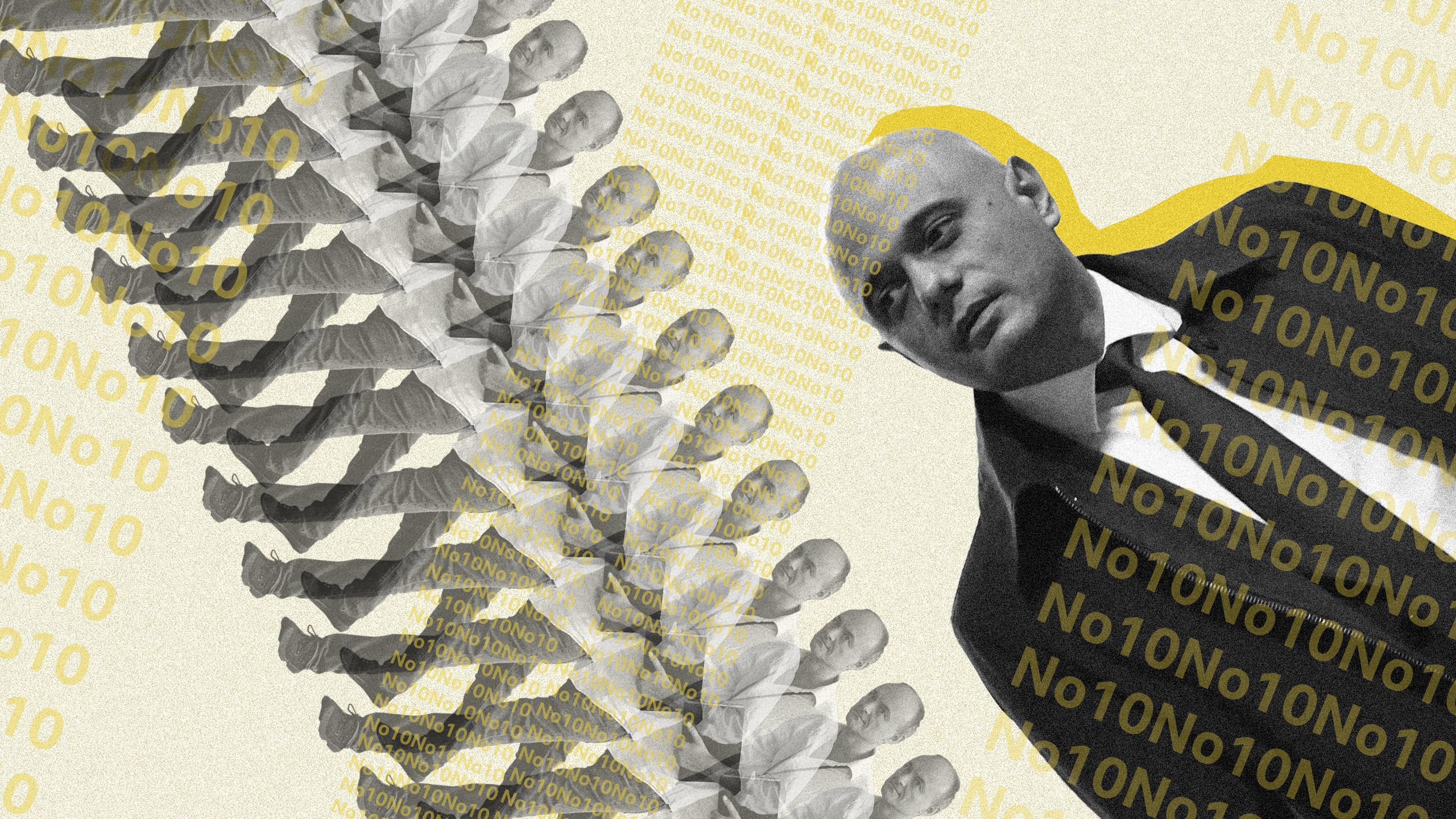

Not so fast, it seems. Cummings is now back with a vengeance after orchestrating a cabinet reshuffle which shook the Conservative Party. Sajid Javid decided to resign as chancellor rather than accept that all his special advisers would have to go, replaced by a joint No 10/Treasury team.

The PM told Javid that he was a valued member of the government. Javid said the ultimatum could not be accepted by any “self-respecting minister” and quit.

Cummings was not present at the No 10 meeting between the prime minister and chancellor, but his handiwork was detected in a brutal display of power to rein in a chancellor unafraid to speak his mind.

Downing Street feared that, as a fiscal hawk who believes in keeping a tight grip on public spending, Javid could undermine its plans for a dramatic increase in spending targeted at northern seats won by the Tories in December’s election.

Losing one battle one week and then triumphing against the mighty Treasury the next raises questions about where Cummings stands in the inevitable power struggles that beset any government. One friend says his influence is best understood by taking a long-term view.

“Dom sees that long game, so when everyone was writing him off last week he was probably thinking, ‘They don’t know what is coming’. And he doesn’t really care about the day-to-day stuff and he never corrects it.”

Cummings is increasingly garnering much attention. His idiosyncratic dress sense, as he walks up Downing Street in a bobble hat with a shirt hanging out of the back of his trousers, is a gift for photographers.

And then there is his carefully crafted mystique. As he faced questions recently about his influence, he resorted to cartoon references that were obscure, unless you happen to be a five-year-old child. Asked by a journalist on his doorstep about the decision of the prime minister to override his advice by pressing ahead with the HS2 rail project, Cummings said: “The night time is the right time to fight crime – I can’t think of a rhyme.”

The cryptic line comes from the theme tune for PJ Masks, a children’s cartoon, in which youngsters wear special outfits to fight dangerous foes in the dead of night.

Cummings had successfully kept himself in the public eye with a comic turn, while appearing to show indifference to the attention.

But behind the part-gruff, part-mannered exterior lurks a rare beast in British politics: a thinker who has read widely, is frustrated with current government structures and who believes that it is only by lobbing proverbial hand grenades into established institutions that anyone can deliver lasting change.

As a public schoolboy who went to Oxford and tends to hang round in aristocratic circles, Dominic Cummings is an unlikely champion of the dispossessed.

But the defining mission of his career is to articulate and channel the frustration of voters who feel alienated by what has been described as the Westminster elite. Identifying the anger of these voters helped him deliver the three unequivocal successes of his career – winning a 2004 referendum, which killed off the then Labour government’s plans for a political assembly in the north-east of England; winning the 2016 Brexit referendum; and finally helping to mastermind last December’s election win as voters in Labour’s “Red Wall” in the north of England defected to the Tories.

Cummings believes the fate of Boris Johnson’s government will depend on whether it delivers for these “left behind” towns where voters feel little connection with the often more affluent cities. That explains his opposition to HS2, an elitist project in his view which links affluent cities and bypasses towns with greater needs.

As Javid found out this week, Cummings will not allow anyone or anything to get in the way of spending that must, in his view, be targeted at the Red Wall. For him it is about more than trying to keep newly acquired seats in the Tory fold. It is about showing that a whole generation of dispossessed voters can have a stake in society.

For now he is focused on major public spending to rebuild an infrastructure neglected during the years of austerity which he opposed. But Cummings believes that, in the longer term, the best hope for such communities lies in improving the state of schools.

His record on education is also an important way of assessing his likely success in Downing Street. It is the only area where he has previously worked in government.

In the final years of opposition before the Tories’ partial win in the 2010 general election, Michael Gove teamed up with Cummings to plan a schools revolution.

During the week, the pair would work on expanding Tony Blair’s academy schools and ushering in a new era of “free schools” that could be set up by parents and voluntary groups.

At the weekends Gove and wife Sarah Vine, a columnist for the Daily Mail, would join other members of the gilded Cameron circle.

Cummings, however, would tell friends of his disdain for “elites” and entertain journalists with regular attacks on the “entitled” Cameron in the run up to the 2010 general election.

When Gove entered the cabinet as education secretary, Cummings acted as an unofficial adviser after Andy Coulson, Cameron’s director of communications, blocked him from working in government. When the tabloid newspaper phone-hacking scandal ended Coulson’s career in politics in early 2011, Cummings finally formalised his role.

He and Gove turned their fire on the “blob”, the word they used for what they considered to be the education “establishment”, including parts of the department they ran, local authorities and teachers’ unions. This ill-defined group was supposedly trying to thwart their schools revolution.

One admirer at the time said that in delivering this vision Cummings was heavily influenced by Lenin, who famously argued that “you cannot make a revolution in white gloves”.

“Dom is a much more successful Leninist than any of the Leninists around Corbyn,” the friend says.

Cummings rather enjoys being compared to the father of the Russian revolution. But when he heard that someone close to Cameron had compared him to Mao, he threw back a quote from the founder of the People’s Republic of China at the Downing Street dilettantes. “A revolution is not a dinner party, comrade,” he would say.

Cummings worked with Gove for just under three years until Cummings resigned in early 2014 out of frustration when his plan to scrap GCSEs was vetoed. That experience shows what Cummings can do if he feels his advice is ignored – just walk out.

Ultimately, however, a cloud hangs over Cummings’s time in government after Cameron was forced to demote Gove in the summer of 2014 from the job he loved to an unlikely job as chief whip – the person charged with trying to enforce parliamentary discipline among MPs. Cameron acted after the party’s election and polling guru Lynton Crosby found that few people understood the schools reforms and teachers had been almost entirely alienated.

Schools reform, one of the coalition’s achievements hailed by Cameron’s Downing Street, had become so toxic that the prime minister felt obliged to demote his closest friend in cabinet after George Osborne.

The subtle and painstaking business of building alliances in government is a wholly different challenge to advocating one simple case in the binary choice offered in a referendum.

Sir Craig Oliver, Cameron’s director of communications who sparred with Cummings in government and then in the Brexit referendum campaign, believes his record in government should serve as a warning to Boris Johnson. “He’s brilliant at creating a kind of guerrilla warfare against the establishment, and he found the weak spots and probed them relentlessly,” Oliver says. “Identifying an enemy and vilifying them is extremely effective. But if you have to negotiate and live with people, for example teachers, it’s unsurprising they don’t like it if you do that. And it starts to work against you.”

Cummings is unlikely to care what the Cameron circle thinks about him. He scorns the former PM who hails, in his eyes, from the “moneyed classes”, those with an easy route from studying Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Oxford into the political world.

Cummings, of course, is no stranger himself to middle-class privilege. As the son of an oil rig construction manager and a special needs teacher, his background was solidly middle class in the north east of England. He attended the fee-paying Durham School and Exeter College, Oxford.

In Tory circles there is a weary raising of the eyebrow at this champion of the dispossessed. Cummings is no stranger to grand – and at times aristocratic – social circles. His father- in-law, Sir Edward Humphry Tyrrell Wakefield, is a former Christie’s expert on antiques and owner of the medieval Chillingham Castle in Northumberland.

For Cummings it appears to be a case of weekends with the aristocracy and weekdays as an outsider in London.

De Beauvoir Deli is something of a haven in Hackney for the well-heeled, both young and old, who graze on roast beetroot and dukkah.

When out of the Westminster fray, Cummings often whiles away hours there, reading the likes of Anna Karenina or composing one of his lengthy blogs.

The blogs serve as a personal manifesto and show his likes and dislikes. He is generally scornful of arts graduates – he is one – and more respectful of maths and science graduates. He is largely self-taught in maths, saying he has been able to yank himself up to postgraduate level.

In a 237-page manifesto, published in 2013, he outlined his core philosophy on education. Cummings borrowed a phrase from the physicist, Murray Gell-Mann, about fostering an “Odyssean education” which encompasses maths and the natural sciences, the social sciences and the humanities and arts. This approach takes its name from the tortuous 10-year journey home of Odysseus after the fall of Troy.

For British readers of an older generation this had echoes of CP Snow, the polymath writer and physical chemist, whose landmark 1959 lecture The Two Cultures bemoaned the gulf between scientists and writers.

In a nod to Snow, Cummings wrote: “Who knows what would happen to a political culture if a party embraced education and science as its defining mission and therefore changed the nature of the people running it and the way they make decisions and priorities.”

Cummings, who studied ancient and modern history at Oxford, provides an insight into his own political tactics by citing at length two giant influences from the ancient and modern worlds. Thucydides, the Athenian general who chronicled the war between Athens and Sparta, and Otto von Bismarck, the “Iron chancellor” who was instrumental in the unification of Germany in 1871.

In his blogs, Cummings cites Thucydides writing of the Battle of Salamis in 480BC: “A man harms his foes thus: those things they most dread he discovers, carefully investigates, then inflicts upon them.” Cummings remembered this lesson in the Brexit referendum.

He is also fond of quoting Bismarck.

“Politics… is the capacity to choose in each fleeting moment of the situation that which is least harmful or most opportune… With a gentleman I am always a gentleman and a half, and with a pirate I try to be a pirate and a half.”

Eyebrows have been raised at Cummings’s interest in such a militaristic figure. But one friend says: “Dominic doesn’t think Bismarck was right to go to war. He may not have approved of the methods and the motive but actually when the task was there he did it.”

Some close to Cummings have advised him in recent years to steer clear of the most contentious element of the “Odyssean education” blog – his interest in genetics. Cummings cited research which claimed that the variation in children’s performance at school is explained in large part by genes. In one example, geneticist Robert Plomin showed that 70% of the variation in scores in phonics tests is down to “heritability” genes, according to Cummings.

In the most controversial section of the manifesto, he wrote that discovering “genes responsible for general cognitive ability and specific abilities and disabilities” would “enable truly personalised education including early intervention for specific learning difficulties”. Cummings added: “When forced to confront such scientific developments, the education world and politicians are likely to handle them badly partly because there is such strong resistance across the political spectrum to accepting scientific evidence on genetics.”

Discussions about the role of genetics in education can be highly controversial – they are way outside the political mainstream. That no doubt fuels Cummings’s interest, though he insists his findings are always based on reading serious academic research.

One former colleague believes Cummings would be well advised to employ an editor to vet his blogs. “Dom doesn’t do the kind of epitome of languid ease with which Brits have officially conducted intellectual life,” the friend says. “But Christ, he needs an editor.”

The blogs shine a light into the soul of this iconoclast who delighted in chucking bricks at the establishment from the day he set foot in the political world. At the turn of the millennium he was an instrumental figure in the Business for Sterling and Europe Yes/Euro No campaign which helped force Tony Blair to abandon his dream of joining the euro. Key themes which helped him win the Brexit referendum nearly 20 years later could be detected. One of its slogans was Keep the Pound, Keep Control.

Cummings first crossed paths at this stage with Matthew Elliott, a veteran Eurosceptic campaigner who would later recruit him to the Vote Leave campaign. When Cummings eventually accepted Elliott’s offer they dispensed traditional Eurosceptic messages about the sovereignty of Parliament and the simple message of taking back control.

As the insurgent, Cummings spearheaded a highly controversial campaign which claimed Britain could not stop Turkey joining the EU (untrue) and made great play of the £350m-a-week the UK sent to the EU. That was a gross figure (deemed “potentially misleading” by the UK Statistics Authority) that failed to account for Britain’s rebate, as well as EU spending in the UK.

Cummings relished the rows with his opponents and at one point sent an internal email saying: “We do all our best work in the gutter.”

Some of his tactics proved too much for Eurosceptic grandees who tried to downgrade Cummings’s position, a “coup” that failed when his senior staff threatened to walk out of the campaign. Relations with Elliott never recovered when he tried to act as a go-between amid the warring factions.

One senior Tory was so alarmed he raised Cummings’s behaviour with Michael Gove. “What you’ve got to understand is, he’s a Leninist,” Gove replied.

“You mean the ends justify the means?” the Tory grandee lamented as the consequences sunk in of having a latter-day revolutionary among their ranks.

There is much to be learnt about the man at the heart of Number 10 from an analysis of the Brexit referendum and Cummings’s role in it. There were moments when emotions spilled out – such as when Cummings punched a hole in the ceiling during the night of celebration following victory.

There were also allegations after the campaign.

In July 2018 the Vote Leave campaign was fined £61,000 by the Electoral Commission for channelling hundreds of thousands of pounds to the Brexit youth group BeLeave allegedly to avoid breaching Vote Leave’s legal £7m spending limit.

The BeLeave group paid just over £675,000 to the Canadian data analytics company, Aggregate IQ. The commission said that BeLeave’s spending was “incurred under a common plan with Vote Leave”. Vote Leave rejected the commission’s findings.

The use of data was one of the most controversial aspects of the Vote Leave campaign which spent more than a third of its £7m budget on services provided by Aggregate IQ, according to the Commons Digital Select Committee. The company targets ads on social media platforms such as Facebook, with those from the BeLeave group being seen five million times on the social media platform.

James Graham, who wrote the screenplay for the Channel Four drama, Brexit: The Uncivil War, said that the intense focus on the use of data during the campaign was a highly sensitive matter for Cummings, whom he first met over a rather drunken pizza session with the other members of the Vote Leave team.

A second meeting, with Benedict Cumberbatch – who played Cummings – in attendance, was held over a dinner of vegan pie at Cummings’s north London house. Graham arrived before Cumberbatch, giving Cummings a chance to raise his concerns about how the drama might deal with the data row.

“Dominic imagined that [the data storyline] was going to be misrepresented as some kind of malign magic potion set free on our country like a chemical gas,” says Graham. “He just wanted to explain exactly what the intention behind that was and how it was used. He wanted to impress upon me they didn’t data mine Britain and it wasn’t so much about targeting. His belief, and of course he might be overselling the other side of this, was that you can obsess too much on the Andy Warhol thing, the medium and the message, you can obsess too much about the delivery mechanism. But it was the message that won.”

After the victory most of the campaign personnel, from Michael Gove down, rowed in behind Boris Johnson in his first effort to become Tory leader.

Cummings supported Johnson but decided he wanted a break. “I’m not going to be around for the leadership campaign, I promised Mary [his wife, the journalist Mary Wakefield] that I wouldn’t,” he told colleagues who went off to work on the Johnson campaign. “I’ll come back if we win.”

Johnson didn’t and Theresa May became prime minister, leaving Cummings with time on his hands. He turned his mind to saving Brexit on the grounds that what he regarded as the timid approach of the new prime minister risked the entire project.

In a prophetic move, he also thought about how Whitehall should be reconfigured in the spirit of his “Odyssean education” approach. By the end of June last year, with May in crisis and Johnson heading for Number 10, Cummings set out his thinking in another lengthy blog.

Cummings focused in particular on two figures – the “brilliant” physicist, Michael Nielsen, and the “genuine visionary” in the computing world, Bret Victor.

For those who find the Cummings blogs a tad impenetrable, this one is illustrated with numerous pictures of low tech cabinet rooms and government emergency centres next to the high tech Nasa control room. Cummings used the photos to show – in his opinion – how ill-prepared government is to deal with unpredictable crises and to harness technology to evolve day-to-day policy.

Cummings believes Victor has the answer with his ideas on work settings as “seeing rooms” which are totally repurposed. Individual computer screens are discarded so that technology uses the whole room as a work space.

Victor’s Dynamic Land building in Berkeley California inspired Cummings with ideas for government.

In his blog, Cummings explains: “It is a large connected set of rooms that have computing embedded in surfaces. For example, you can scribble equations on a bit of paper, cameras in the ceiling read your scribbles automatically, turn them into code, and execute them – for example, by producing graphics… This is all hard to explain/understand because you haven’t seen anything like it even in sci-fi films (it’s telling the media still uses the 15 year-old Minority Report as its sci-fi illustration for such things).”

All food for thought for a strategist with aspirations to change Whitehall, if not the world.

For someone who regards himself as a disruptive outsider, Dominic Cummings has never felt the need to please anyone. And so Boris Johnson had his work cut out when he asked Cummings to join him in Downing Street last July. The new prime minister described it as a “hairy” mission.

One friend recalls: “Boris was really turning the thumbscrews on Dom saying, ‘You’ve got to come in, you’ve got to come in.’”

Cummings tabled what he called a series of “terrorist demands” to the incoming prime minister after judging, according to one friend, that his team had monumentally failed to draw up a coherent plan.

The boldest demand, which was at the centre of the eventual showdown with Sajid Javid, was to be given control of the network of special advisers, the political appointees who work for cabinet ministers. By controlling the special advisers Cummings would gain significant leverage over cabinet ministers.

To his surprise, the new prime minister said yes to his demands. Cummings therefore entered Downing Street with one immediate plan – to sort out the “mess” of Brexit – and a longer vision to transform the workings of government.

“We are going to bulldoze our way to make sure Brexit happens,” was the Cummings view at the time. “It has to happen.”

In a fraught autumn for the Tory party, which saw the evisceration of the pro-European wing of the party, Cummings deployed his own powers, sometimes without mercy.

Relations started to sour with Javid when his special adviser Sonia Khan was unceremoniously and highly controversially marched out of No 10 last August after falling out with Cummings. The sacking of Khan – who was escorted out of Downing Street by an armed police officer – chilled the atmosphere in Whitehall. Javid was not even aware it was happening.

Cummings is not the loner he is sometimes portrayed as, and knows power when he sees it. On the day Johnson became prime minister, a scruffy-looking Cummings made sure to frame himself in the corner of a photo taken as the cabinet secretary and the man in charge of the civil service, Sir Mark Sedwill, welcomed the new PM to No 10. Sedwill could well be seen as the epitome of the sort of generalist – a career flitting between the Foreign Office and the Home Office – scorned by Cummings.

But Gisela Stuart, the former Labour minister who chaired the Vote Leave campaign, who knows both men well, says: “I remember looking at that picture and I thought Sedwill and Dom have a lot in common. Both of them are big picture people, both of them are deeply strategic, both of them are terribly focused. I think they want the same thing.”

With the fate of Brexit unknown in a hung parliament, Cummings advised Johnson to take a risky gamble by going for an early general election.

Cummings is widely praised for pushing for it but was blunt about the dangers at the time. “This election is very risky, very risky for us,” he was heard to say. “Anyone who says they know what is going to happen or thinks we will walk it is an idiot.”

The electoral gamble paid off. But Cummings was unhappy – feeling that his control of special advisers had failed to impose enough discipline. He was highly suspicious of the team working for Javid. Cummings had technically taken control of the network of special advisers but they were still in effect answerable to their cabinet minister and not to him.

Also, Cummings wanted to inject new characters into the machinery of government. He used a blog on 2 January to call on “weirdos and misfits with odd skills” to join him in delivering the large changes in policy and decision-making he said were required by Brexit.

Cummings indicated that 35,000 people had answered his call. They must have been attracted by the job specification in which he wrote: “I don’t want confident public school bluffers. I want people who are much brighter than me who can work in an extreme environment. If you play office politics, you will be discovered and immediately binned.”

But Cummings faced a rebuke from a writer cited in one of his blogs. William Gibson mocked Cummings for appearing to liken himself to the “quasi evil genius” Hubertus Bigend in his novel Pattern Recognition. “The idea of people like that being made bureaucrats is quite unnerving,” Gibson told the BBC.

A former cabinet minister accuses Cummings of ruthless tactics which have involved injecting populism into the political discourse and undermining the constitution when parliament was suspended last year. David Gauke, who stood unsuccessfully as an independent candidate in the election after he was deprived of the Tory whip, says: “You can admire the ruthless determination to pursue a strategy which very few people would do in as determined a manner as he has done. But it is a strategy which is reckless and damaging for the country in the undermining of institutions.”

But the former MP Sir Nicholas Soames, who lost the Tory whip at the same time as Gauke, admires Cummings. Soames, who eventually had the whip restored, says: “Dominic Cummings is an exceptionally gifted and clever man. Every government needs a disruptor. Governments that don’t have disruptors become complacent and run out of steam. The predictable pretend loathing of Cummings is totally pathetic.”

But Cummings has made enemies in a potentially significant camp – friends of Sajid Javid. “The handling of Sajid was gratuitous,” one said. “Is it really wise to create a prince across the water so early on?”

Friends of Cummings are divided on what the future holds for him as he lives with the inevitable compromises of government. One says he is a pragmatist.

But another says that Cummings’s irritation with David Cameron’s vetoing of his plan to scrap GCSEs shows he is prepared to walk. “Dom is not there to please. He’s there to get stuff done. If the principal, Boris, doesn’t follow that plan he will say: ‘You’re not interested in taking my advice, I’m out of here.’”

A divisive polemicist, both charming and abrasive, Dominic Cummings is wielding immense power in the name of a prime minister with an historic mandate. It is a natural meeting of minds between two idiosyncratic political beasts with eclectic interests in the classical world and beyond.

Johnson summoned Cummings in his first hour of need when Brexit and the future of the Conservative party were in jeopardy. Cummings was the right fit for the first phase of Boris Johnson in No 10. It will be a cliffhanger to see how long the match lasts.

. . .