“1968 – the year that haunts hundreds of women”, BBC News Long Read

By Ly Truong, London, 27 March 2020

When Tran Thi Ngai was raped, she did not get justice, or even sympathy. Instead she ended up in prison.

The man had come in to buy soy sauce. Tran Thi Ngai was working as a midwife and nurse, but that morning she was looking after her parents’ shop in southern Vietnam while they were out.

He had grenades hanging from his armour, guns on his belt. It was the summer of 1967, and the Vietnam War – pitting South Vietnamese forces, the US and its allies, against the North Vietnamese Communists – was escalating.

As he approached the counter, he held out the money. As Tran reached to take it, he grabbed her arm, then her hair, and dragged her into the back room of the shop. There he raped her.

“It felt as if my life was over,” Tran says. All she could do was channel her energies into working harder than ever.

When she noticed her stomach swelling she assumed she was just putting on weight. Then one day she felt a kick and realised she was pregnant.

Her parents were horrified that she was expecting a baby out of wedlock – a major taboo. The country’s social mores were heavily influenced by Confucianism, and women were expected to remain virgins until they were married.

“My parents called me ‘chửa hoang’ (pregnant out of wedlock) – they beat me up badly.

“I didn’t want to carry on living. I felt completely dead inside.”

She tried to kill herself several times but survived – “it felt as if the foetus was fighting for me”.

Her parents only stopped beating her once she gave birth – in February 1968. She was overwhelmed by how beautiful her baby girl was, but was soon overtaken by anxiety.

“I was worried about my child growing up, worried about money, worried about how I could get back to work to earn a living.”

She named the baby Oanh. But, hard as it is to comprehend, she wanted to recognise the baby’s father in some way. The middle name would be Kim. That was the soldier’s surname. Her rapist was neither Vietnamese nor American. He was South Korean.

Four years earlier his nation had joined the US in fighting the Communist Vietcong in South Vietnam.

Not long after giving birth, Tran woke one night to find that Kim had appeared again, looking for her.

“He didn’t say a word, stood there for one or two minutes, then left,” she says.

South Korean soldiers (“ROK Tigers”) in Qui Nhon, Vietnam

A few days later, another South Korean soldier arrived. He had been sent by Kim to take Tran and the baby to his base – that of the 28th regiment of the South Korean White Horse Division – in a remote mountainous area south of her home town.

Ashamed and isolated, she felt she had no other choice. She got into the car and spent the next two years with her rapist. She was terrified the entire time, fearing for her life and that of the child.

“It was coercion, rape, no love was there,” she says.

Tran had another baby girl with Kim, before being abandoned when he moved to another base.

Tran Thi Ngai today

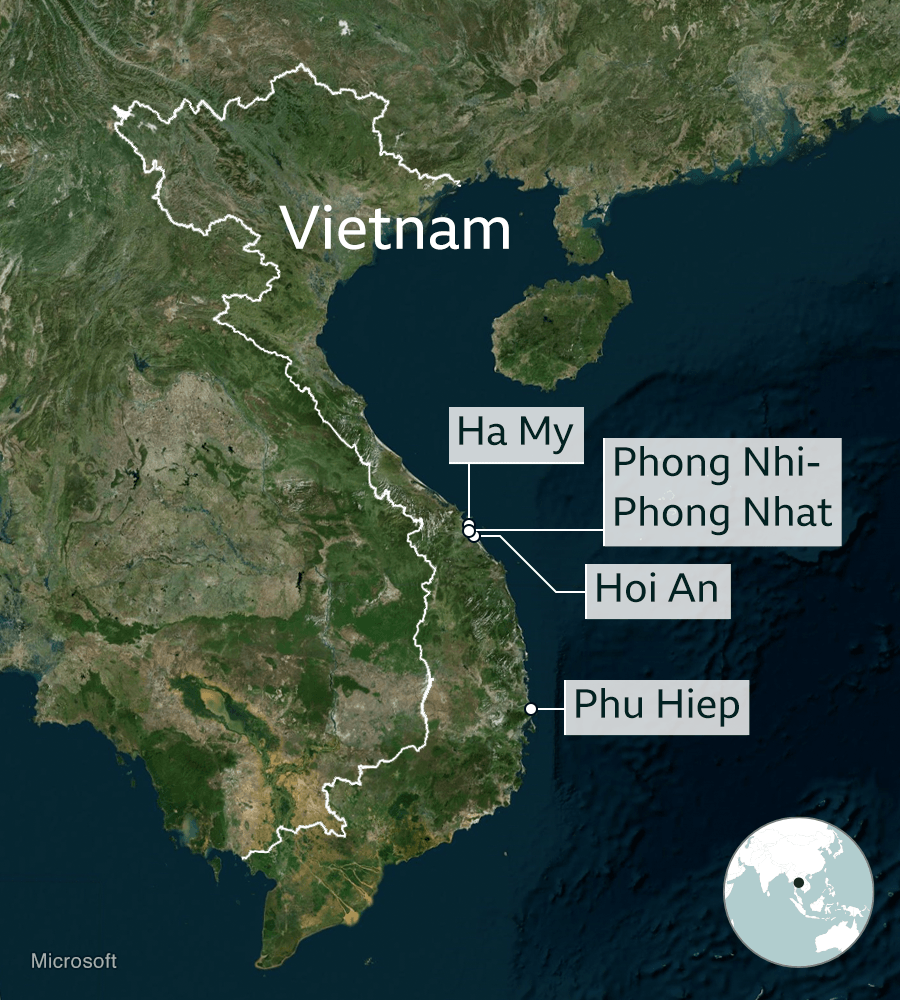

She found her way back to her parents in Phu Hiep, trying to work as many hours as possible to feed her children, until Kim once again sent a comrade to her. But this time the soldier – whose name she recalls was Park – was there, at least ostensibly, to help with the children.

“He carried them in his arms, fed them, cared for them while I was out working.”

And then one day, Park, too, assaulted her. Tran conceived another baby – a boy this time.

Her family’s social standing was now irrevocably damaged.

“It got to a point when living in the village became too difficult. Villagers shunned me, accused me of having a Korean husband, [luring the Koreans] here to kill the Vietnamese,” she says.

She and her parents fled to another part of the province, but her reputation followed her.

“If I introduced myself as ‘Ngai’, people would say ‘Oh yes, Ms Ngai. Beautiful, but she doesn’t have a husband.’”

They would ask her why she hadn’t aborted her children. She says that as a midwife she couldn’t entertain the idea.

“My job was to help other women give birth – I took care of their babies, I carried them, I embraced them, washed them, cut their cords. How could I even think of destroying my own baby?” says Tran, her voice breaking.

Shattered lives

In the same month Tran was giving birth to her first child, 11-year-old Nguyen Thi Thanh’s life was also changing forever.

On the morning of 25 February 1968 Nguyen heard screaming coming from the far side of her village of Ha My – not far from the now-popular tourist town of Hoi An – and saw smoke filling the sky. She ran down the lane to see what was happening. South Korean soldiers were pointing their guns at her.

She ran back to the house to tell her mother, Le Thi Tho, that the village was surrounded.

“As I finished my sentence they poured into our house.”

Later reports were to suggest the soldiers were members of the Blue Dragon Division, a notorious South Korean marine corps.

They ordered her entire family, along with another woman and her children, and a friend of her younger brother, into the underground shelter in their front yard.

They threw grenades in after them, killing Nguyen’s aunt and her infant cousin instantly.

She says her mother tried to shield her and her brother. “‘We are doomed, my baby,’ my mother cried out.

“My whole body was burning and then felt numb… I could see other people’s blood all over me,” Nguyen says.

Nguyen’s eight-year-old brother lost a leg and eventually died of his injuries in hospital. Only Nguyen and one of her cousins, both badly injured, survived, crawling to a neighbour’s for help.

She says that the soldiers then burned her house down.

“I could hear the popping and crackling sounds from burning bamboo. I smelt smoke, fire.”

More than 135 people in Ha My were killed that day, with just a dozen of the villagers surviving, she says.

Although she says South Korean soldiers had regularly visited Ha My before, looking for Vietcong, she has no idea why 25 February 1968 was different.

“We don’t know why they were so aggressive that day. They even killed three and four-month-old babies.”

Nguyen Thi Thanh, pictured at 16, five years after the massacre

What is known is that this period marked a turning point in the Vietnam War.

In late January of that year the North Vietnamese and Vietcong launched the infamous Tet Offensive – a bloody military campaign against the South Vietnamese, the US and their allies. The retaliations were vicious, the most notorious being the My Lai massacre – the gang rape and mass murder of Vietnamese civilians by US troops in March 1968.

Nguyen Thi Thanh today

Nguyen did not witness the immediate aftermath of the killings in Ha My – she was taken to hospital in Da Nang. But her older brother told her he watched as the soldiers returned the next day with tractors to flatten the village, destroying the bodies.

Korean soldiers bulldoze a Vietnamese village, north of Bong Sen

While there has not been an apology for the atrocities perpetrated by the US during the 20-year Vietnam war, there has been an acknowledgement in the form of reparations and a damning war crimes tribunal.

But South Korea’s government, which now has close economic ties with Vietnam, appears unwilling to engage in a review of its role in the war. Seoul sent approximately 320,000 troops in a move analysts say was rooted in a fear of a “domino effect” spread of Communism.

South Korea’s ministry of defence sent a letter to Nguyen and 102 other survivors last September saying it has no record of any civilian killings carried out by its military in Vietnam and there needs to be a joint investigation by both governments in tandem to check the facts, but that this is currently unachievable.

A group of South Korean soldiers with a blindfolded Vietcong suspect

Looking for answers

One woman who has made it her life’s mission to discover the truth is South Korean researcher Ku Su-jeong.

While doing a PhD in Vietnamese history in the 1990s, she was given a document by an official in Vietnam’s foreign ministry, describing atrocities carried out by the South Koreans.

She managed to finally secure an unauthorised copy from a Vietnamese government official for a fee, and has spent the past 20 years visiting Vietnamese villages and talking to survivors.

She believes about 9,000 South Vietnamese civilians were killed in about 80 massacres carried out by the South Koreans, although there is no way of independently verifying her research.

Ku believes there are still other deaths unaccounted for and often hears from people who want her to investigate alleged extra-judicial killings.

“I still receive calls from people who ask me to come to their village,” she says.

Her lifetime of research has come at a personal cost.

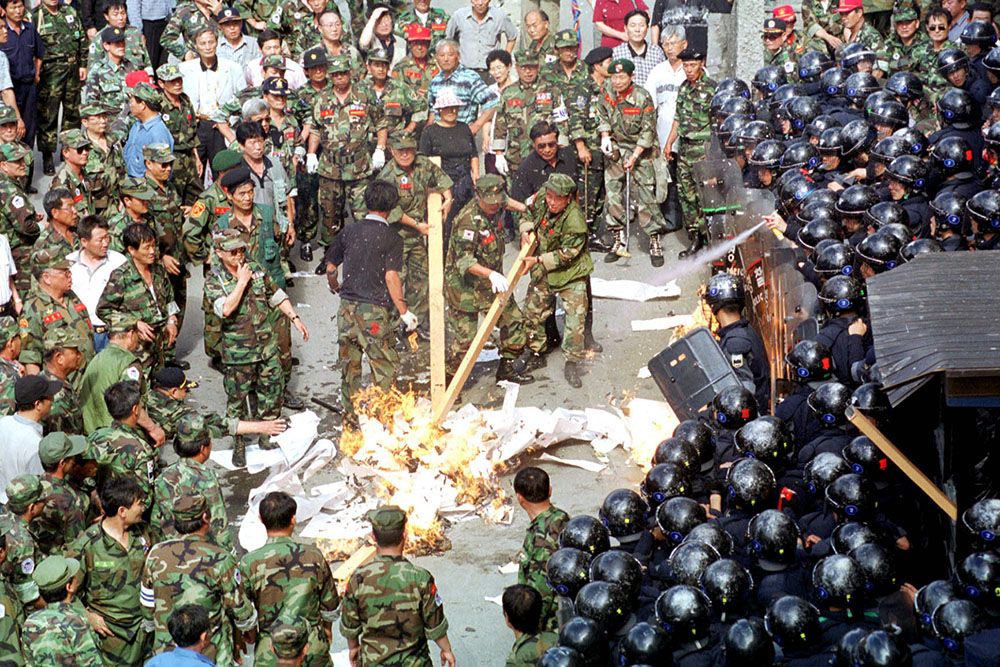

Two months after her findings were published in a South Korean newspaper article in April 1999, about 2,000 veterans in their 50s, all wearing army uniform, gathered in front of the paper’s headquarters in Seoul.

The men trashed the building and some also vandalised Ku’s home, she says. She and her mother had to move to a high security apartment.

The South Korea Veterans’ Association also attempted to sue her for defamation and fraud, although the case was dropped.

It is not possible to prove who was responsible for the massacre that killed Nguyen’s family in Ha My. But one South Korean veteran, Ryu Jin-sung, says his division was responsible for a similar massacre just two weeks before the Ha My killings.

Ryu’s company was on patrol when a bullet was fired at them from the direction of Phong Nhi and Phong Nhat, two villages a few miles from Ha My. Attacks began as retaliation – the company dividing into three units to attack the villages from three different directions.

Ryu Jin-sung

Ryu’s unit was the first to move out, after his comrade shot dead an unarmed elderly man. That evening he heard his comrades boasting about killing young children and women, and the next day he saw bodies of civilians laid out on the side of the road.

“There was a large crowd. When we got there, they yelled and screamed at us. It felt as if they were about to kill me, their eyes fixed on me.

“I used the barrel of my rifle to make my way through. I saw corpses, I saw bereaved families – their anger. Even today it’s still very vivid.”

Ryu says that those who deny a massacre took place in Phong Nhi and Phong Nhat are either misinformed or unwilling to admit the truth.

The BBC arranged a meeting between Ryu and Nguyen, now 63, in a restaurant in Seoul. Both say, like many Vietnamese traumatised by the war, that they are haunted by ghosts. Ryu by that of the old man he saw being shot in Phong Nhi and Phong Nhat; Nguyen by her younger brother.

Nguyen and Ryu meet

After swapping stories of the war, Ryu finally reads out a simple phrase he has prepared in advance in Vietnamese. “I am sorry,” he says. Nguyen simply nods in acknowledgement. He serves her some food, she smiles, and they continue with the meal.

As she leaves the restaurant, Nguyen says she feels a burden has been lifted, but is still holding out hope for an official apology from Seoul.

Asked for comment, the South Korean government told the BBC in a statement that since establishing formal diplomatic relations in 1992, the two countries “have made together continuous efforts to develop their bilateral relations in a future-oriented manner on the basis of the shared view that they should put their unfortunate past behind them and move forward to the future”.

South Korea is now one of Vietnam’s largest investors, with economic giants like Samsung and LG Electronics pouring billions of dollars into building factories there.

South Korean journalist Koh Kyoung-tae, who first published researcher Ku Su-jeong’s controversial findings, says the idea that South Korean soldiers may have carried out atrocities doesn’t fit with the nation’s sense of itself as a victim.

Koh Kyoung-tae

“We Koreans say that we have 5,000 years of history and we’ve always been the victim. We’ve been colonised by Japan, Mongolia, China… and we endured it. It’s kind of like we’re proud of our victim mindset.”

South Korea also spent decades lobbying Japan for a similar apology over the hundreds of thousands of South Korean women forced to work as World War Two sex slaves.

Nguyen, who is deaf in one ear and seriously scarred all over her body as a result of her injuries, blames her own country for ignoring the issue. The Vietnamese government turned down two BBC requests to film for an accompanying documentary.

“Vietnam is afraid of anything that affects the relationship between the two countries so they don’t want to clarify it,” she says.

Back in Phu Hiep, Tran Thi Ngai, now 79, is also still wrestling with the fallout of the war.

She says her children have faced a lifetime of abuse and discrimination, mocked for being “lai dai han” (the Vietnamese term for the children of Vietnamese and Korean parents).

Her father was tortured and beaten to death under house arrest in 1977 as punishment for allowing his daughter to have relations with a South Korean. Tran herself was put in detention or prison three times between 1975 and 1978.

While it has not been possible to verify her specific case, the aftermath of the Vietnam War was an intense period of retribution, the country still riven with division.

“An apology might not be worth much, but it means a lot to us”

Vietnamese pressure group Justice for Lai Dai Han is simply pushing for an apology to the victims of rape by South Korean soldiers and those conceived as a result. There are estimated to be about 800 of the victims’ children still alive.

One prominent campaigner for the group is Tran Thi Ngai’s son, Tran Van Ty, who was beaten up regularly on his way to school for having a South Korean father.

Former UK Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, the international ambassador for the group, says there is no reason why an apology should adversely affect relations “if handled properly.

“Vietnam and South Korea have agreed, ‘Let’s go forward, let’s not look back,’ which I understand, but you’ve got to make exceptions to that sometimes.

“In some cases, in order to look forward you’ve got to settle things in the past.”

The group is pushing for an inquiry by the UN Human Rights Council.

Survivors of the massacres allegedly carried out by the South Korean military also filed a legal case against the South Korean government this month.

If the judge finds grounds to pursue it, the first hearing could be heard as early as this summer – though it is expected to take several years to reach a conclusion.

“An apology might not be worth much, but it means a lot to us,” says Nguyen Thi Thanh.

A bronze sculpture by British artist Rebecca Hawkins is meanwhile touring the UK, inspired by the story of Tran Thi Ngai and her son. “Mother and Child” shows two figures trapped by a strangler fig – a plant native to Vietnam which smothers the trees it wraps around.

“We need the South Koreans to acknowledge what happened,” Tran says. “They sent troops to Vietnam – it wasn’t us who went to their country.”

Left: Tran Thi Ngai with her son Tran Van Ty and the artist Rebecca Hawkins / Right: The sculpture “Mother and Child”

Credits

Author: Ly Truong

Illustration: Jilla Dastmalchi

Researcher: Hyung Eun Kim

Images: Derrick Evans, Getty Images, Alamy

Online Producer: James Percy

Editor: Sarah Buckley

Published: 27 March 2020

Asked for comment, the South Korean government told the BBC in a statement that since establishing formal diplomatic relations in 1992, the two countries “have made together continuous efforts to develop their bilateral relations in a future-oriented manner on the basis of the shared view that they should put their unfortunate past behind them and move forward to the future”.

South Korea is now one of Vietnam’s largest investors, with economic giants like Samsung and LG Electronics pouring billions of dollars into building factories there.

South Korean journalist Koh Kyoung-tae, who first published researcher Ku Su-jeong’s controversial findings, says the idea that South Korean soldiers may have carried out atrocities doesn’t fit with the nation’s sense of itself as a victim.

Koh Kyoung-tae

“We Koreans say that we have 5,000 years of history and we’ve always been the victim. We’ve been colonised by Japan, Mongolia, China… and we endured it. It’s kind of like we’re proud of our victim mindset.”

South Korea also spent decades lobbying Japan for a similar apology over the hundreds of thousands of South Korean women forced to work as World War Two sex slaves.

Nguyen, who is deaf in one ear and seriously scarred all over her body as a result of her injuries, blames her own country for ignoring the issue. The Vietnamese government turned down two BBC requests to film for an accompanying documentary.

“Vietnam is afraid of anything that affects the relationship between the two countries so they don’t want to clarify it,” she says.

Back in Phu Hiep, Tran Thi Ngai, now 79, is also still wrestling with the fallout of the war.

She says her children have faced a lifetime of abuse and discrimination, mocked for being “lai dai han” (the Vietnamese term for the children of Vietnamese and Korean parents).

Her father was tortured and beaten to death under house arrest in 1977 as punishment for allowing his daughter to have relations with a South Korean. Tran herself was put in detention or prison three times between 1975 and 1978.

While it has not been possible to verify her specific case, the aftermath of the Vietnam War was an intense period of retribution, the country still riven with division.

Asked for comment, the South Korean government told the BBC in a statement that since establishing formal diplomatic relations in 1992, the two countries “have made together continuous efforts to develop their bilateral relations in a future-oriented manner on the basis of the shared view that they should put their unfortunate past behind them and move forward to the future”.

South Korea is now one of Vietnam’s largest investors, with economic giants like Samsung and LG Electronics pouring billions of dollars into building factories there.

South Korean journalist Koh Kyoung-tae, who first published researcher Ku Su-jeong’s controversial findings, says the idea that South Korean soldiers may have carried out atrocities doesn’t fit with the nation’s sense of itself as a victim.

Koh Kyoung-tae

“We Koreans say that we have 5,000 years of history and we’ve always been the victim. We’ve been colonised by Japan, Mongolia, China… and we endured it. It’s kind of like we’re proud of our victim mindset.”

South Korea also spent decades lobbying Japan for a similar apology over the hundreds of thousands of South Korean women forced to work as World War Two sex slaves.

Nguyen, who is deaf in one ear and seriously scarred all over her body as a result of her injuries, blames her own country for ignoring the issue. The Vietnamese government turned down two BBC requests to film for an accompanying documentary.

“Vietnam is afraid of anything that affects the relationship between the two countries so they don’t want to clarify it,” she says.

Back in Phu Hiep, Tran Thi Ngai, now 79, is also still wrestling with the fallout of the war.

She says her children have faced a lifetime of abuse and discrimination, mocked for being “lai dai han” (the Vietnamese term for the children of Vietnamese and Korean parents).

Her father was tortured and beaten to death under house arrest in 1977 as punishment for allowing his daughter to have relations with a South Korean. Tran herself was put in detention or prison three times between 1975 and 1978.

While it has not been possible to verify her specific case, the aftermath of the Vietnam War was an intense period of retribution, the country still riven with division.

“An apology might not be worth much, but it means a lot to us”

Vietnamese pressure group Justice for Lai Dai Han is simply pushing for an apology to the victims of rape by South Korean soldiers and those conceived as a result. There are estimated to be about 800 of the victims’ children still alive.

One prominent campaigner for the group is Tran Thi Ngai’s son, Tran Van Ty, who was beaten up regularly on his way to school for having a South Korean father.

Former UK Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, the international ambassador for the group, says there is no reason why an apology should adversely affect relations “if handled properly.

“Vietnam and South Korea have agreed, ‘Let’s go forward, let’s not look back,’ which I understand, but you’ve got to make exceptions to that sometimes.

“In some cases, in order to look forward you’ve got to settle things in the past.”

The group is pushing for an inquiry by the UN Human Rights Council.

Survivors of the massacres allegedly carried out by the South Korean military also filed a legal case against the South Korean government this month.

If the judge finds grounds to pursue it, the first hearing could be heard as early as this summer – though it is expected to take several years to reach a conclusion.

“An apology might not be worth much, but it means a lot to us,” says Nguyen Thi Thanh.

A bronze sculpture by British artist Rebecca Hawkins is meanwhile touring the UK, inspired by the story of Tran Thi Ngai and her son. “Mother and Child” shows two figures trapped by a strangler fig – a plant native to Vietnam which smothers the trees it wraps around.

“We need the South Koreans to acknowledge what happened,” Tran says. “They sent troops to Vietnam – it wasn’t us who went to their country.”

Left: Tran Thi Ngai with her son Tran Van Ty and the artist Rebecca Hawkins / Right: The sculpture “Mother and Child”

This story is part of the Crossing Divides season, bringing people together in a fragmented world

Credits

Author: Ly Truong

Illustration: Jilla Dastmalchi

Researcher: Hyung Eun Kim

Images: Derrick Evans, Getty Images, Alamy

Online Producer: James Percy

Editor: Sarah Buckley

Published: 27 March 2020

Asked for comment, the South Korean government told the BBC in a statement that since establishing formal diplomatic relations in 1992, the two countries “have made together continuous efforts to develop their bilateral relations in a future-oriented manner on the basis of the shared view that they should put their unfortunate past behind them and move forward to the future”.

South Korea is now one of Vietnam’s largest investors, with economic giants like Samsung and LG Electronics pouring billions of dollars into building factories there.

South Korean journalist Koh Kyoung-tae, who first published researcher Ku Su-jeong’s controversial findings, says the idea that South Korean soldiers may have carried out atrocities doesn’t fit with the nation’s sense of itself as a victim.

Koh Kyoung-tae

“We Koreans say that we have 5,000 years of history and we’ve always been the victim. We’ve been colonised by Japan, Mongolia, China… and we endured it. It’s kind of like we’re proud of our victim mindset.”

South Korea also spent decades lobbying Japan for a similar apology over the hundreds of thousands of South Korean women forced to work as World War Two sex slaves.

Nguyen, who is deaf in one ear and seriously scarred all over her body as a result of her injuries, blames her own country for ignoring the issue. The Vietnamese government turned down two BBC requests to film for an accompanying documentary.

“Vietnam is afraid of anything that affects the relationship between the two countries so they don’t want to clarify it,” she says.

Back in Phu Hiep, Tran Thi Ngai, now 79, is also still wrestling with the fallout of the war.

She says her children have faced a lifetime of abuse and discrimination, mocked for being “lai dai han” (the Vietnamese term for the children of Vietnamese and Korean parents).

Her father was tortured and beaten to death under house arrest in 1977 as punishment for allowing his daughter to have relations with a South Korean. Tran herself was put in detention or prison three times between 1975 and 1978.

While it has not been possible to verify her specific case, the aftermath of the Vietnam War was an intense period of retribution, the country still riven with division.

“An apology might not be worth much, but it means a lot to us”

Vietnamese pressure group Justice for Lai Dai Han is simply pushing for an apology to the victims of rape by South Korean soldiers and those conceived as a result. There are estimated to be about 800 of the victims’ children still alive.

One prominent campaigner for the group is Tran Thi Ngai’s son, Tran Van Ty, who was beaten up regularly on his way to school for having a South Korean father.

Former UK Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, the international ambassador for the group, says there is no reason why an apology should adversely affect relations “if handled properly.

“Vietnam and South Korea have agreed, ‘Let’s go forward, let’s not look back,’ which I understand, but you’ve got to make exceptions to that sometimes.

“In some cases, in order to look forward you’ve got to settle things in the past.”

The group is pushing for an inquiry by the UN Human Rights Council.

Survivors of the massacres allegedly carried out by the South Korean military also filed a legal case against the South Korean government this month.

If the judge finds grounds to pursue it, the first hearing could be heard as early as this summer – though it is expected to take several years to reach a conclusion.

“An apology might not be worth much, but it means a lot to us,” says Nguyen Thi Thanh.

A bronze sculpture by British artist Rebecca Hawkins is meanwhile touring the UK, inspired by the story of Tran Thi Ngai and her son. “Mother and Child” shows two figures trapped by a strangler fig – a plant native to Vietnam which smothers the trees it wraps around.

“We need the South Koreans to acknowledge what happened,” Tran says. “They sent troops to Vietnam – it wasn’t us who went to their country.”

Left: Tran Thi Ngai with her son Tran Van Ty and the artist Rebecca Hawkins / Right: The sculpture “Mother and Child”

This story is part of the Crossing Divides season, bringing people together in a fragmented world

Credits

Author: Ly Truong

Illustration: Jilla Dastmalchi

Researcher: Hyung Eun Kim

Images: Derrick Evans, Getty Images, Alamy

Online Producer: James Percy

Editor: Sarah Buckley

Published: 27 March 2020