Issue of the Week: War

Nuclear Arms Control Era Comes to End Amid Global Rush for New Weapons, The New York Times, February 5-9, 2026

The End of Civilization As We Knew It, Part Thirty Four

Today, David E. Sanger and William J. Broad followed up their article last Thursday, which combined (below), should be the most terrifying things you’ve ever read.

Not long ago, millions were in the streets all the time, the headlines and TV news dominated by one issue–the looming obliteration of life on earth by nuclear war, humanity revolting against it, and real progress made to change it.

Now we sit on our asses and bemoan it for a moment along with everything else, in between the next entertainment distraction for those who could do something sane to help themselves and their children and their species survive, and those, the majority, struggling every second for a crumb to survive by.

You, who are in that small percentage among all of humanity who have security, are in backward time travel now, experiencing what it is to be alive on a living planet. Before long, this will all be darkness, physical and metaphysical, because of so many of you who chose it, who could be–would be if their was any natural impulse left to resist drowning in nihilsm and distraction and momentary self-gratification and delusion of whatever–rising up with the fortitude of a species that will not go quietly into the night.

We’ve addressed this issue for many years, underlined in our post on March 1, 2024, which pressaged what is happening now, and in our post on August 1, 2025, which did so further. Here are excerpts from those posts, followed by today’s and last thursday’s seminal articles in The New York Times:

Issue of the Week, March 1, 2024

From the moment that the atom bomb was dropped to end World War Two, through 45 years of the Cold War between the US and its allies and the Soviet Union and its allies, the omnipresent issue for everyone alive was that their lives and all life on earth could be obliterated in a second by nuclear war–and almost was.

Then, Cold War over. As we’ve written at length, for a moment, it appeared democracy and peace were breaking out all over.

Nuclear weapons?

Out of sight, out of mind.

Except they never went away. They just spread, under increasingly far more unstable circumstances than ever.

The New York Times has once again provided an historic service by reminding us that the number one threat of instant destruction of the planet and all life is nuclear war.

And that it just almost happened.

And that unless full public consciousness is focused again on the threat of nuclear weapons, we are all history.

We’ve done a lot of work on this issue over the years. We produced a unique documentary on the issue at the height of Cold War tensions just before it ended, aired on PBS stations nationwide. We will revisit this and present the film in a post in the future.

But the point here is that when we say that there is nothing more important or more powerfully presented than the opinion piece and launch of the Times series on nuclear war, we know what we’re talking about.

As we wrote in our first post of the year:

“The movie Oppenheimer is a great movie, not the greatest ever as a film, but perhaps the most important for many reasons. [And if it doesn’t win Best Picture and many other awards at the Oscars, what’s left of Hollywood should obliterate itself]. But one reason predominates: It is the story of the creation and first use of the atomic bomb. The ending is the most stunning and critical piece of film ever. The icon of physics, Albert Einstein, who urged FDR to build the atomic bomb to counter the Nazi program to do the same, who then urged that it not be used against the Japanese, had been seen in snippets during the film talking with J. Robert Oppenheimer, who ran the program to build the bomb, but the conversation is never heard. Then at the end, it is, as reported in Vulture:

As Einstein turns to leave, Oppenheimer reminds him of an earlier conversation they had before the testing of the first atom bomb, when the Manhattan Project physicists were worried that the chain reaction caused by the atomic bomb might never end — that it could proceed to ignite the Earth’s atmosphere and destroy the planet.

“When I came to you with those calculations,” Oppenheimer tells Einstein, “we thought we might start a chain reaction that might destroy the entire world.”

“What of it?” Einstein asks.

“I believe we did,” Oppenheimer says.

The point is clear. Nuclear war will annihilate life on earth at some point.”

Here is the launching piece of the series in the Times. For a graphic experience you will never forget, go to the piece through the links:

OPINION

AT THE BRINK

A SERIES ABOUT THE THREAT OF

NUCLEAR WEAPONS IN AN UNSTABLE WORLD

Introduction by Kathleen Kingsbury, Opinion Editor

THE THREAT OF nuclear war has dangled over humankind for much too long. We have survived so far through luck and brinkmanship. But the old, limited safeguards that kept the Cold War cold are long gone. Nuclear powers are getting more numerous and less cautious. We’ve condemned another generation to live on a planet that is one grave act of hubris or human error away from destruction without demanding any action from our leaders. That must change.

In New York Times Opinion’s latest series, At the Brink, we’re looking at the reality of nuclear weapons today. It’s the culmination of nearly a year of reporting and research. We plan to explore where the present dangers lie in the next arms race and what can be done to make the world safer again.

W.J. Hennigan, the project’s lead writer, begins that discussion today by laying out what’s at stake if a single nuclear weapon were used, as well as revealing for the first time details about how close U.S. officials thought the world came to breaking the decades-long nuclear taboo.

Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, threatened in his 2024 annual speech that more direct Western intervention in Ukraine could lead to nuclear conflict. Yet an American intelligence assessment suggests the world may have wandered far closer to the brink of a nuclear launch more than a year earlier, during the first year of Mr. Putin’s invasion.

This is the first telling of the Biden administration’s efforts to avoid that fate, and had they failed, how they hoped to contain the catastrophic aftermath. Mr. Hennigan explores what happened during that tense time, what officials were thinking, what they did and how they’re approaching a volatile future.

IN THE FIRST ESSAY OF THE SERIES, W.J. HENNIGAN LAYS OUT THE RISKS OF THE NEW NUCLEAR ERA AND HOW WE GOT HERE. YOU CAN LISTEN TO AN ADAPTATION OF THE PIECE HERE.

Within two years, the last major remaining arms treaty between the United States and Russia is to expire. Yet amid mounting global instability and shifting geopolitics, world leaders aren’t turning to diplomacy. Instead, they have responded by building more technologically advanced weapons. The recent intelligence on Russia’s development of a space-based nuclear weapon is the latest reminder of the enormous power these weapons continue to wield over our lives.

There is no precedent for the complexity of today’s nuclear era. The bipolarity of the Cold War has given way to a great-power competition with far more emerging players. With the possibility of Donald Trump returning as president, Iran advancing its nuclear development and China on track to stock its arsenal with 1,000 warheads by 2030, German and South Korean officials have wondered aloud if they should have their own nuclear weapons, as have important voices in Poland, Japan and Saudi Arabia.

The latest generation of nuclear technology can still inflict unspeakable devastation. Artificial intelligence could someday automate war without human intervention. No one can confidently predict how and if deterrence will work under these dynamics or even what strategic stability will look like. A new commitment to what could be years of diplomatic talks will be needed to establish new terms of engagement.

Over the past several months, I’ve been asked, including by colleagues, why I want to raise awareness on nuclear arms control when the world faces so many other challenges — climate change, rising authoritarianism and economic inequality, as well as the ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Part of the answer is that both of those active conflicts would be far more catastrophic if nuclear weapons were introduced into them. Consider Mr. Putin’s threat at the end of February: “We also have weapons that can strike targets on their territory,” the Russian leader said during his annual address. “Do they not understand this?”

The other answer lies in our recent history. When people around the world in the 1960s, ’70s, ’80s and early ’90s began to understand the nuclear peril of that era, a vocal constituency demanded — and achieved — change.

Fear of mutual annihilation last century spurred governments to work together to create a set of global agreements to lower the risk. Their efforts helped to end atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, which, in certain cases, had poisoned people and the environment. Adversarial nations started talking to each other and, by doing so, helped avoid accidental use. Stockpiles were reduced. A vast majority of nations agreed to never build these weapons in the first place if the nations that had them worked in good faith toward their abolishment. That promise was not kept.

In 1982 as many as a million people descended on Central Park calling for the elimination of nuclear arms in the world. More recently, some isolated voices have tried to raise the alarm — Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, said last year that “the most serious thing facing mankind is nuclear proliferation” — but mostly such activism is inconceivable now. The once again growing threat of nuclear weapons is simply not part of the public conversation. And the world is less secure.

Today the nuclear safety net is threadbare. The good news is that it can be restitched. American leadership requires that Washington marshal international support for this mission — but it also requires leading by example. There are several actions that the U.S. president could take without buy-in from a Congress unlikely to cooperate.

As a first step, the United States could push to reinvigorate and establish with Russia and China, respectively, joint information and crisis control centers to ensure that misunderstandings and escalation don’t spiral. Such hotlines have all but gone dormant. The United States could also renounce the strategy of launching its nuclear weapons based only on a warning of an adversary’s launch, reducing the chance America could begin a nuclear war because of an accident, a human or mechanical failure or a simple misunderstanding. The United States could insist on robust controls for artificial intelligence in the launch processes of nuclear weapons.

Democracy rarely prevents war, but it can eventually serve as a check on it. Nuclear use has always been the exception: No scenario offers enough time for voters to weigh in on whether to deploy a nuclear weapon. Citizens, therefore, need to exert their influence well before the country finds itself in such a situation.

We should not allow the next generation to inherit a world more dangerous than the one we were given.

This is the introduction to a new Opinion series about the modern nuclear threat. Read the first essay of the series, where W.J. Hennigan lays out the risks of the new nuclear era and how we got here.

. . .

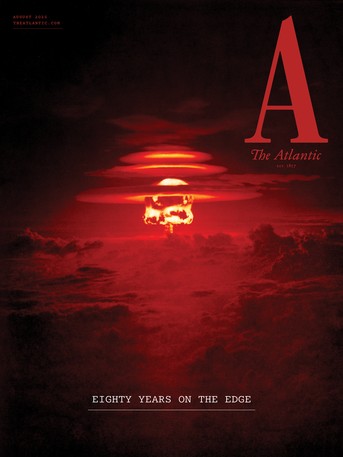

Issue of the Week, August 1, 2026

Eighty Years On The Edge, The Atlantic Magazine, August 2025

The End Of Civilization As We Knew It, Part Thirty

Often, for 26 years, our posts have covered or referenced the singular existential threat to all life on the planet Earth, and perhaps beyond, of nuclear weapons.

Our work in our documentaries and public service ad campaigns has emphasized this since the beginning, 48 years ago at the official founding of Planet Earth Foundation, and for years before leading up to this.

The two most likely things to lead to nuclear war are:

1) All the regional, national and global instability caused by all the other issues we address–hunger, environment, economic opportunity, human rights, population, disease–in other words the inequality and lack of security related to basic human needs and rights not being met for a majority of the population of the world, from struggling to make it to extreme poverty.

and;

2) the very existance of nuclear weapons.

And more and more, a third issue. Other technologies taking over the mechanisms ranging from control to launch. Error has always been a threat, from human to technological. But in the age of AI no one knows what dark territory we may be entering into.

There is also the conundrum of the threat of the weapons themselves and the use of them to blackmail others into virtual slavery. Tricky as it gets. The simplistic notion that the weapons can never be used and all the notions that have and can flow from this are akin to a unique psychosis. Any nations with these weapons and many without but under the umbrella of those who do, are never going to surrender their freedom and become the equivalent of serfs by the threat of another nation to use them. The fact of the imperative of agency in the human marrow against the imperative of survival is a standoff that has worked, barely, for eighty years. A blink of the eye.

It will not keep working for much longer.

No weapon created that leaps past those of the past in any age has not been used. It is the very unique capacity of nuclear weapons to destroy everything that has deterred their use. Sometimes the threat to use them has deterred a larger conflagration. But the day is coming soon when all the forces that create all the instability in the world will overcome this, and armageddon will be unleashed. If we’re lucky, a limited use will shock everyone, led by the strongest powers, to their senses, the world will unite as if an alien invasion has occurred, and the underlying causes will finally be addressed.

If we’re lucky.

Creating a world of equality was the goal of the United Nations allies at the end of the World War Two, the war that saw the creation of nuclear weapons because Hitler was racing toward doing so.

The horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki eighty years ago was exhibit number one in holding everyone back from using these weapons again. Plus they became exponentially more powerful.

But as much progress toward equality–basic needs and rights for all–as was made, even when stymied by the Cold War, and when it seemed it was launched forward with irresistable force with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the monied interests, as Roosevelt called them, the richest interests in the world, became more rich and powerful than imaginable with economic inequality becoming more extreme by far than at any time in modern history. And this is in one completely inter-related world. As has been written here before, we are long past any attempts, such as those currently underway, to revert to nationalism as if the fact of globalism will go away. Everything everywhere affects everything. There is only one escape from doomsday, a world with global rules and governance to at least the extent needed for survival which has as its basis basic needs and rights met for everyone, in a sustainable way that protects the environment we all rely on, therefore protects all life on the planet.

A tall order. But it always has been, and the progress chart over the ages is astonishing. The problem is the downside of the race between blind corruption of greed and hubris of the powerful few and the well being of the great majority of people and the planet, and the outcome that leads to transformation or destruction.

The odds are getting far worse at the moment. The number of nations with nuclear weapons is probably about to double or worse, after being close to going in the other direction. The most dangerous wars and conflicts since World War Two are raging. Democracy versus dictatorship as the future of humanity in one world are at stake throughout as well.

This is not a spectator sport. The involvement of everyone, not as ideological sloganeers, but as people of multidimensional knowledge and values, will likely determine the outcome. Get to work.

All of our work and observations and that of others we have gathered over the decades is a resource for anyone who is serious as a person of values–a member of a species dedicated to the nurturing and survival of its children, therefore its species.

On this singular issue of the threat of nuclear weapons, Ross Anderson has written a masterful history and current analysis on where things stand as part of the August Atlantic Magazine’s cover story, Eighty years on the edge.

Here’s an excerpt:

Nuclear weapons can be thought of as a kind of cancer that started metastasizing through human civilization in 1945. A few times during the Cold War, this cancer threatened to kill off much of humanity, but a partial remission followed the fall of the Berlin Wall. The U.S. and the Soviet Union agreed on a limit of 6,000 deployed warheads each—still enough to destroy most of the world’s major cities many times over, but down from the tens of thousands that they’d previously stockpiled.

The high-water mark for the disarmament movement came in 2009, when President Obama called for a world without nuclear weapons. For this address, Obama chose Prague, the site of the Velvet Revolution. He cast his eyes over a crowd of thousands that morning, and then over the whole continent. Peace had come to Europe, he said. Now it was time to go further, and negotiate a new arms-control treaty with Russia. The very next year, the two countries committed to cap themselves at 1,550 deployed warheads. At the time, China still had fewer than 300. Disarmament wasn’t on the near horizon, but the trajectory was favorable.

How long ago that moment now seems. The world’s great-power rivalries have once again become fully inflamed. A year after invading Ukraine in 2022, Putin suspended his participation in the capping agreement with the United States. He has begun to make explicit nuclear threats, breaking a long-standing taboo. Meanwhile, the Chinese have slotted more than 100 ICBMs in deep desert silos near Mongolia. The military believes that the U.S. has to target these silos, and Russia’s silos, to deter both countries, and doing so eats up “a big chunk of our capped force,” the former senior official at the Pentagon told me. Nuclear strategists in both of America’s major parties are now pushing for a larger arsenal that could survive a simultaneous attack from Russia and China. Those two countries will likely respond by building still more weapons, and on the cycle goes.

. . .

Now back to today, only a few months since the Atlantic piece, Eighty Years on the Edge, and three years since The New York Times in-depth series “The Brink”.

Now, here we are:

Newly Unbound, Trump Weighs More Nuclear Arms and Underground Tests

It remains to be seen whether the three big nuclear powers are headed into a new arms race, or whether President Trump is trying to spur negotiations on a new accord now that a last Cold War treaty has expired.

Listen to this article · 8:37 min Learn more

By David E. Sanger and William J. Broad

Feb. 9, 2026

In the five days since the last remaining nuclear treaty between the United States and Russia expired, statements by administration officials have made two things clear: Washington is actively weighing the deployment of more nuclear weapons, and it is also likely to conduct a nuclear test of some kind.

Both steps would reverse nearly 40 years of stricter nuclear control by the United States, which has reduced or kept steady the number of weapons it has loaded into silos, bombers and submarines. President Trump would be the first president since Ronald Reagan to increase them again, if he chose to do so. And the last time the United States conducted a nuclear test was 1992, though Mr. Trump said last year that he wanted to resume the detonations “on an equal basis” with China and Russia.

So far, the statements from the Trump administration have been vague. It has said that it is looking at a variety of scenarios that might bolster the arsenal by reusing nuclear arms now in storage, and that Mr. Trump has instructed his aides to resume testing. But no one has specified how many weapons may be deployed or what kind of tests could be conducted. The details matter, and may determine whether the three big nuclear powers are headed to a new arms race, or whether Mr. Trump is trying to force the other powers into a three-way negotiation on a new treaty.

“It’s all a bit mysterious,’’ said Jill Hruby, a longtime nuclear expert who, until last year, ran the National Nuclear Security Agency, a part of the Energy Department that designs, tests and manufactures American nuclear weapons. “It is very confusing what they are doing.”

The indications started within hours of the expiration on Thursday of New START, which limited the number of weapons that the United States and Russia could deploy to roughly 1,550 each. Mr. Trump turned down an offer from President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia for an informal extension of the 15-year treaty — which would not be legally binding — while both countries considered negotiating a successor treaty.

That same day, the State Department sent its under secretary for arms control and international security, Thomas G. DiNanno, to Geneva to address the Conference on Disarmament. The treaty, he complained in a speech, “placed unilateral constraints on the United States that were unacceptable.” And he noted that in Mr. Trump’s first term the president had pulled out of two previous treaties with Russia — the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty and the Open Skies Treaty — because of Russian violations.

He repeated a familiar case, which many Democrats in the national security world have also voiced, that the New START treaty failed to cover whole new classes of nuclear weapons that Russia and China are developing, and that any new treaty would have to place limits on Beijing, which has the fastest-growing nuclear force on the globe.

Then he noted that the United States was now free “to strengthen deterrence on behalf of the American people.” The United States will “complete our ongoing nuclear modernization programs,” he said — a reference to hundreds of billions of dollars being spent on new silos, new submarines and new bombers — and noted that Washington “retains nondeployed nuclear capability that can be used to address the emerging security environment, if directed by the president.”

One option, he noted, is “expanding current forces” and “developing and fielding new theater-range nuclear forces,” the shorter-range nuclear weapons that Russia has deployed in abundance. (New START covered only “strategic” weapons that can be launched halfway around the world.)

One imminent surge centers on the nation’s Ohio-class submarines. Each of the 14 underwater craft have 24 tubes that can launch nuclear-tipped missiles. To comply with the New START limits, the Navy disabled four tubes on each sub. Now, relieved of those restrictions, plans are moving ahead to reopen the tubes — allowing the loading of four more missiles onto each sub. In all, that move alone will add up to hundreds of more warheads that can threaten the nation’s adversaries.

It is possible, of course, that such deployments are intended only to push other nuclear powers into negotiations, a familiar form of nuclear poker during the Cold War. But it is also possible that Russia and China decide they would rather expand their forces.

China has, until now, shown little interest in arms control, at least until its forces approximate the size of Washington’s and Moscow’s. As Franklin Miller and Eric Edelman, two nuclear strategists who served in past Republican administrations, noted in Foreign Affairs last year, China “regards any willingness to engage in arms control as a sign of weakness, and it views the transparency and verification process that would presumably undergird such an accord as intrusive and akin to espionage.”

In his speech in Geneva, Mr. DiNanno also gave the first detailed explanation by a Trump administration official for what the president meant last year when he ordered a restart of nuclear arms testing. Mr. Trump made his carefully worded “on an equal basis” statement just before his October meeting with President Xi Jinping of China. In an interview last month with The New York Times, Mr. Trump said he had spoken at length with Mr. Xi on nuclear issues. But he gave no details.

Initially, some American nuclear experts outside the government saw Mr. Trump’s remarks as meaning that the United States planned the kind of powerful underground nuclear tests that were frequent symbols of the tit-for-tat Cold War competition a half century ago. The tests were detonated underground, sending shock waves radiating into the earth’s crust and from there ricocheting around the globe. The blasts were easy to detect.

And while the United States, Russia and China have suspended those kinds of tests — observing the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty even though the U.S. Senate has never ratified it — North Korea ignored it. Between 2006 and 2017 it conducted six underground tests, shattering the hopes for a global moratorium.

The testing ban, which took effect in 1996, forbids tests that produce any explosive force whatsoever, no matter how minuscule. It is called a “zero-yield” treaty.

But some experts have long had a different view of Mr. Trump’s remarks, interpreting them as calling for relatively small tests that would release no detectable shock waves. The absence of earthshaking explosions make these tests nearly impossible to detect.

In his Geneva talk, Mr. DiNanno made clear that the Trump administration believed that Russia and China had already conducted such tests, and he suggested that the president’s call for testing “on an equal basis” might allow the United States to do the same.

Mr. DiNanno said the U.S. government knew that China had conducted “nuclear explosive tests” it sought to conceal. He specifically pointed to one on June 22, 2020, toward the end of Mr. Trump’s first term.

The main global network that seeks to monitor adherence to the test ban said in a recent statement that it had detected no test explosion on that date. And American officials say that over the past five years, American intelligence experts have debated whether or not the Chinese government actually conducted the test. But Mr. DiNanno expressed no doubt.

“DiNanno’s comments surprised me,” said Terry C. Wallace, a former director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory who long studied China’s program of nuclear experimentation. “They had no caveats” rooted in the field’s uncertainties, he said.

In his talk, Mr. DiNanno said Beijing used “decoupling” to hide its testing. He was referring to a technique that bomb designers use to separate the shock waves of a nuclear detonation so that they make no impact on the earth’s crust. The means include bottling up a small explosion in a container behind superstrong walls of steel.

The United States knows the process well: From 1958 to 1961, long before the global test ban, American nuclear weapons designers conducted more than 40 such tests, even though there was a U.S.-Soviet test moratorium.

In his talk, Mr. DiNanno did not detail the implications of his claims. But he repeated the “on an equal basis” wording, suggesting that the United States was headed in that direction, too. There was some ambiguity, however. He said that the United States was eager to “restore responsible behavior when it comes to nuclear testing” but gave no indication of what he meant by “responsible.”

David E. Sanger covers the Trump administration and a range of national security issues. He has been a Times journalist for more than four decades and has written four books on foreign policy and national security challenges.

William J. Broad has reported on science at The Times since 1983. He is based in New York.

. . .

Nuclear Arms Control Era Comes to End Amid Global Rush for New Weapons

Beijing, Moscow and shaken American allies are seeking new warheads as President Trump ends more than a half century of nuclear arms control with Russia.

Listen to this article · 18:47 min Learn more

By David E. Sanger and William J. Broad

David E. Sanger and William J. Broad have covered nuclear proliferation and arms control for The Times for more than four decades.

- Published Feb. 5, 2026Updated Feb. 6, 2026

The deadline has been looming over Washington and Moscow for years.

On Thursday, the last nuclear arms control treaty between the United States and Russia expired. For the first time since 1972, it leaves both superpowers with no limits on the size or structure of their arsenals, at the very moment both are planning new generations of nuclear weapons and newly evasive means of delivering the deadly warheads.

Despite a new era of superpower confrontation, talks over a new treaty — or even an informal extension of the current one — never got off the ground, frozen by the war in Ukraine. When President Trump was asked in January why he had not taken up President Vladimir V. Putin’s offer for a one-year informal extension, he shrugged.

“If it expires, it expires,” he told The New York Times in an interview. “We’ll do a better agreement” after the expiration, he insisted, adding that China, which has the world’s fastest-growing nuclear arsenal, and “other parties” should be part of any future accord. The Chinese have made clear they are not interested.

On Thursday afternoon, after the New START treaty’s expiration, Mr. Trump reiterated his call for a new accord, denouncing the previous one as “a badly negotiated deal” and declaring on social media that “we should have our nuclear experts work on a new, improved, and modernized treaty that can last long into the future.” But he said nothing about agreeing with Mr. Putin to freeze American and Russian arsenals at current levels, leaving open the possibility of a renewed arms race.

In fact, the United States has been preparing for that possibility, and the Navy is already preparing to deploy more nuclear warheads on its biggest submarines. Meanwhile, Russia and China are now testing new types and configurations of nuclear weapons that few envisioned when the Senate, by a narrow margin, ratified New START in 2010.

Arms control was not supposed to end this way.

When President Richard M. Nixon signed the first arms limitation treaty with the Soviet Union, the banner headlines signaled a new era in which even the most hostile of Cold War rivals saw the danger of letting the arms race spin out of control.

Those early efforts had so many loopholes that the Soviet and American arsenals grew fast, peaking at roughly 62,000 nuclear arms in the late 1980s. But then the numbers fell, treaty by treaty. By 2009, President Barack Obama, speaking to thunderous applause in Prague, vowed to pursue “a world without nuclear weapons,” though he conceded the abolition might not come in his lifetime.

Few post-Cold War predictions have collapsed as dramatically as that one. As Vipin Narang and Pranay Vaddi, two of the nation’s leading nuclear strategists, who both served in the Biden administration, wrote recently: “Nuclear weapons are back with a vengeance.”

While the U.S. and Russia have cut down their stockpiles …

… other countries are building up their nuclear arsenals.

Source: Federation of American Scientists

Ashley Cai/The New York Times

The evidence is everywhere, from Mr. Putin’s plans for undersea and space-based nuclear arms to Xi Jinping’s decision to abandon China’s “minimum deterrent” and build an arsenal clearly designed to rival those of Washington and Moscow.

Mr. Trump’s first-term vow to disarm North Korea pushed the reclusive nation in the other direction, and his second-term confrontations with Europe have led its leaders to wonder if they can count on America’s “nuclear umbrella” — the promise that Washington would come to the defense of nonnuclear allies if they ever came under nuclear attack.

Not surprisingly, they’re now talking about establishing nuclear forces independent of Washington’s.

Mr. Trump’s National Security Strategy, issued in December, barely touches on these new dynamics. Only the Pentagon’s annual report on Chinese military power cites its massive buildup — 600 weapons, on the way to more than 1,000 by 2030, according to U.S. intelligence estimates — and it skirts a more immediate danger: Mr. Putin’s repeated, barely veiled threats to use nuclear weaponson the battlefield in Ukraine.

Mr. Trump is hardly the only one arguing that China needs to be part of any new arms control effort. As Beijing and Moscow maneuver in an uneasy cooperative effort to challenge the United States, a growing number of experts argue that the two nuclear superpowers could coordinate their nuclear strategy — ultimately prompting Washington to deploy hundreds of additional weapons.

Earlier this week, Mr. Obama, who pushed through New START, warned that the United States was about to “pointlessly wipe out decades of diplomacy, and could spark another arms race.”

Yet what stands out in Thursday’s expiration of the New START treaty is the lack of public discussion on the best way forward for American strategy, in contrast to how it once dominated presidential debates, policy arguments, newspaper headlines and Hollywood films.

From the 1950s to the early 1990s, every serious politician on the national stage was expected to be conversant in the subject. Henry Kissinger’s “Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy” was a best seller. “Dr. Strangelove” captured the nation’s deep anxieties.

While there are glimpses today of renewed concerns, there is little public discussion about whether the Trump administration is countering the reinvigorated nuclear threat or fueling it.

Still, in the arms control world, many agree with elements of Mr. Trump’s argument that New START aged poorly and that a new treaty needs added participants.

“You wouldn’t negotiate the same treaty again,” Rafael Grossi, the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, the United Nations’ nuclear inspection body, said in an interview in the agency’s Vienna headquarters. “There are new technologies that are not covered by the treaty — hypersonic missiles, undersea nuclear weapons, space weapons. And there are many other countries that, for one reason or another, feel now as if they may need a nuclear arsenal of their own.”

Mr. Grossi, who is running for secretary general of the United Nations, was too diplomatic to name those nations. But Japan, South Korea, Turkey and Poland are among the nonnuclear weapon states now discussing whether they need to change course.

And the United States itself is doubling down. Washington is spending $87 billion this year on nuclear weapons, including a modernization of its warheads and a hugely expensive replacing of aging missiles and bombers. When Mr. Trump announced a new kind of warship known as the “Trump class,” he quickly added that the vessels would be armed with nuclear-capable cruise missiles, similar to some of the weapons China and Russia are now developing.

“We’re seeing the end to an era of arms control,” said Erin D. Dumbacher, a senior security fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. Washington, she added, seems to have little interest in negotiating “something as big as a follow-on to New START.”

The Umbrella: How Washington Sparked an Age of Nuclear Restraint

In late 1945, just months after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, J. Robert Oppenheimer issued a warning about a lesson he had learned in devising those atomic bombs for the Manhattan Project.

“They’re not too hard to make,” the suddenly famous physicist told his colleagues at Los Alamos, the lab in New Mexico that made the novel weapons. “They’ll be universal if people wish to make them universal.”

Oppenheimer’s worst fears did not materialize, nor did President John F. Kennedy’s grim prediction that by 1975 there could be up to 20 nuclear-armed states.

There are several reasons their predictions proved too pessimistic, but a central factor was the U.S. “nuclear umbrella.” While the United States helped two close allies — Britain and France — make small nuclear arsenals, the strategy of “extended deterrence” kept most American allies from building their own.

After the Soviet Union broke up, more than a dozen Central and Eastern European states joined the NATO alliance, and thus gained the protection of the American nuclear umbrella. All told, on and off, it covered nearly 40 nations.

To the surprise of doom-mongers, the policy helped keep the peace. Graham Allison, a Harvard political scientist who wrote the first major book about the Cuban missile crisis, the closest the Soviet Union and the United States came to a nuclear exchange, noted that “if you told anyone in 1945 that we’re going to see 80 years without another use of nuclear weapons in war, people would have said you’re out of your mind.”

Equally miraculous, he said, is that the world today has only nine nuclear-weapon states — the result of not only the umbrella but of a global nonproliferation system, overseen by Mr. Grossi of the atomic agency, that lets states develop peaceful nuclear power as long they agreed to never make atomic weapons.

Of those nine, four have refused to sign or have renounced the nonproliferation treaty so that they could build their own arsenals: India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea. (The other five were the “original” nuclear-weapon states: the United States, Russia, China, Britain and France.)

Each of the nine adds, in different ways, to the global challenge of safely navigating the nuclear age. Even so, the numbers, and associated risks, are much smaller than what Oppenheimer and Kennedy foresaw.

The Disarray: How Trump Shook the Global Nuclear Order

In 1987, a New York real estate mogul by the name of Donald J. Trump decided to attack a central tenet of American foreign policy.

Our allies, he wrote in full-page ads taken out in The New York Times and other newspapers, should “pay for the protection we extend.” The financial result, he added, would end deficits, cut taxes and “let America’s economy grow unencumbered” by the need to defend rich foreigners.

Now, four decades later, his nationalist views appear to have hardened. And while Mr. Trump often speaks about the fearsome power of nuclear weapons, he has presided over the disassembly of some of the main nuclear restraints that have largely worked — with some near-misses — for eight decades.

As he did in those ads, Mr. Trump still portrays allies as freeloaders and has made clear that in an America First world, American safety and prosperity rank above defending foreigners. His National Security Strategy put it bluntly: “The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over.”

Mr. Trump has repeatedly cast doubt on whether he would use nuclear weapons to protect allies, although he has not formally renounced the American nuclear umbrella.

Just days after Mr. Trump’s famous televised argument with President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine in the Oval Office last February, President Emmanuel Macron of France warned that Europe needed to prepare for America’s retreat from its traditional defense commitments and rethink how it would face a belligerent Russia. Mr. Macron said he was willing to discuss extending the protection of France’s nuclear arsenal to its European allies, and Germany’s new chancellor, Friedrich Merz, welcomed the possibility.

Poland’s prime minister, Donald Tusk, held similar talks and saidhis nation had to drastically build up its military and even “reach for opportunities related to nuclear weapons.” And Mr. Zelensky has said it was a mistake to give up the weapons it held after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Early last month, as Mr. Trump’s threats to take over Greenland grew louder, Stockholm’s leading newspaper called for a joint Nordic nuclear arsenal independent of the United States.

“No one wants to discuss Swedish nuclear weapons,” it declared, “but we must.”

It is hard to know how serious the behind-the-scenes discussions are, and how much is mere talk, driven by nationalist politics or anger at Mr. Trump. But experts say as many as 40 nations have the technical skill, and in some cases the needed material, to build a bomb.

The question is whether they have the political will. Gideon Rose, a foreign policy expert at Columbia University and the Council on Foreign Relations, recently noted that the psychological barriers that bar proliferation “may already have fallen away.”

The Buildup: How Trump Bolsters the U.S. Nuclear Arsenal

Already, there are signs that the Trump administration is planning to break out of the numeric limits of the New START treaty — not dramatically, but in ways that could easily trigger a new arms race. Along the way, they will make the most deadly element of the American arsenal even more deadly.

That increase centers on the nation’s Ohio-class submarines. The undersea craft, 14 in all, are the largest in the American fleet. Each one is 560 feet long — longer than the Washington Monument is high.

Each submarine is built with 24 tubes that can launch missiles, and each missile carries up to eight nuclear warheads. They include some that are 30 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima.

To comply with the limits of New START, the Navy disabled four tubes on each sub. Now, relieved of those restrictions, plans are moving ahead to reopen the tubes — allowing the loading of four more missiles onto each sub.

For the Ohio fleet overall, that’s 56 more missiles and possibly hundreds more warheads, each of which can be aimed at a different target.

Mr. Trump has never discussed that plan, or given a speech on his nuclear strategy, although he signed an executive order to create a “Golden Dome” defense system meant to intercept rockets and missiles.

When he speaks on the subject of nuclear weapons, he talks about his determination that the United States remain dominant. As his security strategy put it, the nation must have “the world’s most robust, credible, and modern nuclear deterrent.”

The “One Big Beautiful Bill” — Mr. Trump’s signature domestic legislation — includes the schedule for the Ohio submarine nuclear upgrades, saying the obligated funds should not be spent before March 1 — that is, a little more than three weeks after New START expires.

To Trump administration officials, this planned increase in deployed weapons puts foes on notice that, if they attempt a nuclear strike, the retaliation could be larger than at any time in years. But there’s a counterargument: America’s deployment of new weapons, and the Golden Dome if it ever gets off the drawing board, could fuel an arms race in which spirals of moves and countermoves raise the global risk of nuclear miscalculation and war.

Monica Duffy Toft, director of the Center for Strategic Studies at Tufts University, noted recently that when one state tries to increase its security, “others often feel less secure and respond in ways that leave everyone worse off.” Arms control agreements, she added, “emerged precisely to dampen this dynamic.”

The Response: How U.S. Rivals Seek to Counter Washington

When New START was negotiated, it covered only traditional “strategic” weapons, which can be delivered to targets on the other side of the world by bombers, submarines and ground-launched missiles. And it had only two signatories, the United States and Russia. China was considered such a small player, with less than 200 weapons, that it was barely discussed as the treaty was debated in the Senate.

Today, the world looks very different. Russia is experimenting — and claims to be preparing to deploy — what experts call new kinds of “superweapons” that Mr. Putin began to announce in 2018, during Mr. Trump’s first term.

In October, he announced a successful test of the Poseidon, an underwater drone meant to cross an ocean, detonate a thermonuclear warhead and raise a radioactive tsunami powerful enough to shatter a coastal city.

“There is nothing like this in the world,” Mr. Putin said, adding that no interception was possible. Pentagon analysts say Poseidon’s small nuclear reactor gives it a range of 6,000 miles and a speed of more than 60 miles per hour — much faster than any submarine.

For years, many experts dismissed Mr. Putin’s boasts about the Poseidon as bluster. But now the weapon appears to be real — as do his test launches to prepare for placing a nuclear weapon in space, a plan the Biden administration quietly warned Congress about two years ago. Both weapons could serve the same purpose: to defeat Mr. Trump’s Golden Dome.

Other concerns about Russia center on Mr. Putin’s repeated threats to use nuclear arms in Ukraine, eroding the taboo against wielding a nuclear weapon in a nonnuclear conflict. The most urgent fears arose in October 2022, when the Biden administration picked up intelligence that preparations for such a strike were underway. Emerging accounts of those events suggest it was a much closer call than officials acknowledged at the time.

China is also developing novel arms. In 2021, it fired a hypersonic missile into orbit that circled the globe — and flew over the continental United States — before deploying a maneuverable glide vehicle that could deliver a nuclear weapon anywhere on earth. Gen. Mark A. Milley, then the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called the test “very close” to a “Sputnik moment” for the United States.

But for the time being it is the speed with which China’s conventional nuclear forces are growing that has seized the attention of Washington. A December report by the Pentagon stressed not only the increase in long-range weapons that could reach the United States but “highly precise theater weapons” that might be employed in a conflict over Taiwan — largely to keep the United States away.

Every effort by the Trump administration to engage China in some kind of discussion of its nuclear capabilities has been shut down by the Chinese, much as they refused to discuss the topic with Biden administration officials.

That leaves the United States with a choice: It can push ahead with larger arsenals and new, specialized weapons to keep pace with Beijing and Moscow, or negotiate a broader deal of the kind Mr. Trump talked about last month.

To give such talks a chance, “Trump should agree with Putin on a ‘strategic pause’ — and possibly extend it to two or three years,” Matthew Bunn of Harvard’s Belfer Center wrote recently. “He should also push Putin to include inspections.”

There is no evidence that will happen. Instead, strategists see a looming surge in moves and countermoves around the globe that could spark a crisis.

Richard L. Garwin, a nuclear expert who advised 13 presidents, concisely described the danger shortly before he died last year at age 97.

“It’s the number of nuclear weapons,” he said in an interview. “The threat is when you have so many.”

David E. Sanger covers the Trump administration and a range of national security issues. He has been a Times journalist for more than four decades and has written four books on foreign policy and national security challenges.

William J. Broad has reported on science at The Times since 1983. He is based in New York.

- Issue of the Week: War

- “Yoshua Bengio, Turing Award winner: ‘There is empirical evidence of AI acting against our instructions’”, El Pais

- Issue of the Week: Human Rights

- “Landmark moment as Dame Sarah Mullally to become first female Archbishop of Canterbury”, The Independent

- “Believe Your Eyes”, The Atlantic

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017