Issue of the Week: Economic Opportunity

The Power of the Fed, Frontline, PBS, July 13, 2021

On Tuesday, July 13, our favorite ongoing US documentary series, Frontline on PBS, will air The Power of the Fed. The program covers perhaps the most important, powerful and least understood impact on the US, and therefore world, economies, the US Federal Reserve.

We are holding this spot in place for the airing and will post the transcript and links to the broadcast below as soon as it airs.

The policies of the Federal Reserve have been for some time, and are now more than ever, largely determining in the end the issues of inequality, economic security, who has basic needs met and who does not.

The impact of Fed policy took on a new dimension of determining the economic future after the great recession in 2008 and has taken on an even more historic impact since the Covid pandemic.

The “Fed” is not the sole determinor of these issues by any means, but its central role is impossible to overstate.

Here is the program. It is as much must viewing and reading as anything we’ve ever posted:

Frontline, PBS, July 13, 2021

TRANSCRIPT.

NEWSREADER:

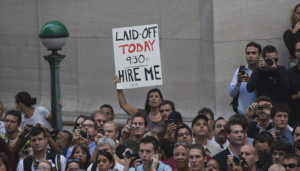

The coronavirus pandemic has left millions of Americans out of work—

FOOD PANTRY VOLUNTEER:

The people have gone now without four or five or six or seven paychecks, and it’s starting to catch up. They need food. It’s the most basic thing.

JAMES JACOBY, Correspondent:

Over the past year we’ve seen how many Americans are living on the edge.

REPORTER:

Have you got any income at the moment?

FEMALE SPEAKER:

No. No. And we have kids, too, so—

REPORTER:

So you’re not making any money at the moment.

FEMALE SPEAKER:

No.

JAMES JACOBY:

But while businesses were shuttered and millions were left unemployed, one place has been thriving like never before.

NEWSREADER:

Stocks surging even as America enters its darkest chapter yet of this pandemic.

JAMES JACOBY:

On Wall Street, it was a banner year.

NEWSREADER:

The market has been open for 30 minutes and we’ve gone straight up.

NEWSREADER:

—the Dow rising nearly 18%, its best performance since 1987.

JAMES JACOBY:

After a major dive, markets reached record highs. The pandemic would turn out to be a blip in the longest bull market ever. The price of stocks have skyrocketed, and so has the wealth of those who own them.

NEWSREADER:

Elon Musk has added over 10 billion to his wealth just this week!

JAMES JACOBY:

Some see signs of mania—

ROARING KITTY, Social media personality:

This GameStop situation, we will never encounter a setup like this again.

JAMES JACOBY:

—as more Americans try to get in on the party.

STANLEY DRUCKENMILLER, Investor:

Right now we’re in a raging mania.

JAMES JACOBY:

Some worry a crash is to come.

JEREMY GRANTHAM, Co-founder, GMO LLC:

It’s the burst of euphoria that typically brings these things to an end.

JAMES JACOBY:

As the financial world has been diverging from the real world, I’ve been trying to understand the many forces at play, and I found one institution has been at the center of it all: the Federal Reserve, the nation’s central bank.

DION RABOUIN, Markets editor, Axios, 2018-21:

It is the most powerful and least understood institution in the country. And it really is difficult to overstate how important this story is and how big this story is and how much it matters.

JAMES JACOBY:

I’ve been speaking to current and former Fed officials—

Is that really the first time you’re in a suit since COVID?

RICHARD W. FISHER, Pres. & CEO, Fed. Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2005-15:

From the waist down.

SHEILA BAIR, Chair, FDIC, 2006-11:

Can I take my mask off?

JAMES JACOBY:

—economists and titans of finance.

HOWARD MARKS, Co-chairman, Oaktree Capital Mgt.:

Nobody knows how this is going to turn out. This is an experiment.

JAMES JACOBY:

I’ve heard that over and over—that we’re living through an epic experiment run by the Fed.

ANDREW HUSZAR, Fmr. Federal Reserve Bank of NY:

I believe this is the economic story of our time.

JAMES JACOBY:

An experiment that has been dramatically changing the American economy.

NEWSREADER:

The Dow is expected to open down—

NEWSREADER:

Right now, breaking news here: Stocks all around the world are tanking because—

JAMES JACOBY, Correspondent:

If you want to understand how today’s financial world has grown so far removed from the real world and the role of the Federal Reserve, you need to go back to 2008, when investors, speculators and Wall Street bankers nearly brought down the global economy.

STOCK MARKET FLOOR TRADER:

Right? Get on the train, otherwise it’s going to leave the station without you.

NEWSREADER:

Wall Street shaken to its very foundation today.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA:

We will need to stabilize, repair and reform our banking system and get credit flowing again to families and businesses.

JAMES JACOBY:

The new president and Congress spent hundreds of billions of dollars to restart the economy, but at the center of the rescue effort was the Federal Reserve. Richard Fisher was the head of the Fed’s bank in Dallas at the time.

RICHARD W. FISHER, Pres. & CEO, Fed. Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2005-15:

What the Federal Reserve does is provide the blood supply for the body of our capitalist economy. And what happened in 2008 is all the veins and the capillaries and the arteries collapsed. So every financial function had failed. It had collapsed, and we had to restore them.

JAMES JACOBY:

That’s when the Fed stepped in. Its job is to promote employment and keep inflation in check, primarily by raising and lowering short-term interest rates. In 2008, Fed officials decided to do something they hadn’t done in half a century: They began dropping rates, eventually to almost zero.

FINANCIAL REPORTER:

Those massive rate cuts have not been stimulating the economy, so it’s the other things—

JAMES JACOBY:

With Americans still suffering and the banking system on the verge of collapse, Fed officials there at the time told me they felt compelled to go even further.

RICHARD W. FISHER:

And then the question was, “What else can we do?” And the committee came up with the idea of quantitative easing.

NEWSREADER:

Quantitative easing. What in the world is it that?

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR:

Quantitative easing. That’s just a Greek term to a lot of people.

NEWSREADER:

A lot of people want to know what they’re going say about what we call quantitative easing. What are some of the nontraditional—

JAMES JACOBY:

Quantitative easing, or QE, was championed by Ben Bernanke, then the Fed chairman.

REPORTER:

Mr. Bernanke, what is the solution to the financial crisis?

BEN BERNANKE:

The Federal Reserve has been putting the pedal to the metal. So we’re doing everything we can to support the economy, and we hope that that’s going to get us going next year sometime.

JAMES JACOBY:

QE was an experimental way for the Fed to inject money into the financial system and lower long-term interest rates. The way they did it was to literally create new money and use it to buy huge amounts of things like mortgage-backed securities and government debt from banks and other institutions. Their hope was that the lower rates would spark more spending and borrowing throughout the economy.

RICHARD W. FISHER:

It’s almost like alchemy. You can create money out of thin air if you’re at the central bank. So creating more money puts more money in the banking system, put more money out there for the economy to take it and put it to work and to grow and to restore itself.

JAMES JACOBY:

As news of the Fed’s actions spread throughout the financial world, Andrew Huszar, a former Fed official who’d left to work on Wall Street, got the offer of a lifetime.

ANDREW HUSZAR, Fmr. Federal Reserve Bank of NY:

I was sitting in a cafeteria in Stamford, Connecticut, when I got the call. I was eating a sandwich—I almost choked on it at the time [laughs]. Basically, I realized very quickly what I was being asked. I was being asked if I would manage the largest financial markets intervention by a government in world history.

JAMES JACOBY:

The job was to join the Fed office in Manhattan and manage a massive expansion of its power in the financial markets under QE, buying more than a trillion dollars in mortgage bonds from the banks as quickly as possible.

ANDREW HUSZAR:

The idea was that the Fed was trying to get more credit and cheaper credit into the hands of the average American. There were millions of people losing their jobs, millions of people in mortgages that they couldn’t afford, and how could the Fed use its financial tools to actually help the average American?

JAMES JACOBY:

Is this something that had ever been attempted before?

ANDREW HUSZAR:

No. You have to realize we were on the midst of the next Great Depression. This was an incredible collapse of the fundamental structure of the U.S. economy in a very short period of time, and we were building the plane while we were flying it.

WILLIAM COHAN:

Everything in the markets is a confidence game. So the Fed exists to restore confidence when all confidence is lost.

JAMES JACOBY:

William Cohan is a writer and former banker who worked with us during our months reporting this story.

The idea of lowering interest rates and the idea of quantitative easing was basically pulling out all the stops to make it cheaper to borrow.

WILLIAM COHAN:

Basically, by making money so inexpensive, by suddenly it being abundant and cheap and easy to get, they just flooded the zone with capital.

JAMES JACOBY:

Easy money.

WILLIAM COHAN:

Easy money. Trillions of dollars of easy money. The greatest experiment in easy money in history.

JAMES JACOBY:

All that easy money sparked a rally in the stock market.

RICHARD W. FISHER:

We saw it take its effect almost immediately. The market reacted. I was a little bit surprised it took off that fast.

JAMES JACOBY:

How was that viewed inside of the boardroom? Was that seen as success?

RICHARD W. FISHER:

Yes. It validated what we thought would happen. That’s what we thought would happen. When you drive interest rates down all the way out, it forces investors into taking bigger steps on the risk spectrum. Cheap money is the fuel for a financial speculator and for a financial investor.

JAMES JACOBY:

What Fisher and other former Fed insiders told me is that the stock market rally was no accident. By design, the Fed’s QE program effectively lowered long-term interest rates, making safer investments like bonds less attractive and riskier assets like stocks more attractive. It was hard to argue with the results: Stock prices kept going up.

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR:

The old saying is “don’t fight the Fed.”

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR:

Don’t fight the Fed.

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR:

Don’t fight the Fed.

FINANCIAL REPORTER:

Rule number one as a young trader you’re taught is don’t fight the Fed.

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR:

I don’t know what the hangover’s going to look like down the road from all this extraordinary stimulus, but for now the markets love it. Don’t fight the Fed.

MALE SPEAKER:

A cam, roll one.

JAMES JACOBY:

You look at me. So we’re approximating an in-person interview. It’ll work, it’ll work.

Mohamed El-Erian remembers it well. He was running the largest bond fund in the world at the time and made a fortune for his firm following the Fed’s lead.

MOHAMED A. EL-ERIAN, Chief Economic Advisor, Allianz:

Don’t fight the Fed. The Fed is the one institution that has a printing press in the basement, and there’s no limits to how much it can use. That is what makes the Fed such an influential player in the marketplace.

Keep an eye on the Treasury market.

JAMES JACOBY:

El-Erian’s firm helped advise the Fed on its QE experiment. He told me the expectation was that the low interest rates and QE would have a strong knock-on effect on the wider economy.

MOHAMED A. EL-ERIAN:

That was the theory. In practice, the Fed was very successful in terms of moving asset prices. It was much less successful in moving the economy, and the result of that is we got the largest disconnect ever between Main Street and Wall Street—between the economy and finance.

FINANCIAL REPORTER:

The banks are sitting on their butts and they’re still not lending money, and until that happens—

JAMES JACOBY:

One of the problems was that the banks were holding on to a lot of the money instead of making it available to borrowers.

NEWSREADER:

The banking sector is broken.

JAMES JACOBY:

At the Fed, Andrew Huszar was disappointed by what he was seeing.

ANDREW HUSZAR:

I have great respect for the Fed. I never questioned, and to this day I will never question the intention. What I question, rather, is whether their tools are able to help the American people in the way that they believe.

I came out of QE1 100% believing that it was necessary, because we had actually helped to stabilize the economy, but wondering if there wasn’t a fundamental problem with the approach in that the tools of the Fed worked through the Wall Street banks and in so doing were disproportionately benefiting the wrong people—the people who didn’t really need the help.

JAMES JACOBY:

So basically what you’re saying is that you were seeing in practice something very different than what was supposed to happen theoretically.

ANDREW HUSZAR:

Yeah. I saw that Wall Street is a private sector actor, and Wall Street has its own interests, and Wall Street can do what Wall Street wants. And the Fed was, on some level, at the mercy of Wall Street.

JAMES JACOBY:

Huszar and others inside the Fed had been counting on Congress to step in and help correct the imbalance—target more money to Main Street and the wider economy.

But then politics took a sharp turn.

SEN. RAND PAUL (R-KY):

We’ve come to take our government back!

JAMES JACOBY:

Tea Party supporters put Republicans in charge of the House—

SEN. RON JOHNSON (R-WI):

We need to restore fiscal sanity to this nation.

JAMES JACOBY:

—dimming prospects for Congress and the White House to work together to stimulate the economy.

The Fed was on its own.

Was it palpable that the Fed was sort of the only game in town here?

RICHARD W. FISHER:

Yes. The fact was we were carrying the load all by ourselves.

JAMES JACOBY:

The day after the midterm elections, the Fed announced it would do another round of quantitative easing—not just to stabilize the economy, but boost it.

Fed Chair Bernanke promoted the plan, writing that it would create a “virtuous circle,” with lower mortgage rates making housing more affordable and higher stock prices boosting consumer wealth.

He went on television to counter critics who were warning the decision risked causing inflation.

BEN BERNANKE:

What they’re doing is they’re looking at some of the risks and uncertainties associated with doing this policy action. What I think they’re not doing is looking at the risk of not acting.

JAMES JACOBY:

I wanted to talk to Bernanke, but he would not agree to an interview.

But I did speak to Sarah Bloom Raskin, who was on the board of governors at the time.

SARAH BLOOM RASKIN, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, 2010-14:

So, many of these tools had not been tried before. They were definitely “break the glass” kind of tools. “What are we going to do in order to restart the economy here?”

JAMES JACOBY:

You voted for Quantitative Easing 2. What was your thinking there?

SARAH BLOOM RASKIN:

Right. So my thinking was that we still had an economy that was far from its potential. As QE began, it showed great promise. We started to see that people’s sense of economic well-being was ticking up somewhat. People were finding jobs. People were finding homes. The foreclosure rate had slowed. So there was a sense that something was working. And for that reason it was, in my mind, worth supporting.

JAMES JACOBY:

But outside the Fed, some were saying that the costs of quantitative easing might already outweigh the benefits.

JOSEPH STIGLITZ:

A lot of talk about quantitative easing, QE2. The likelihood that that will have a significant effect is close to zero.

REPORTER:

But the markets love it.

JAMES JACOBY:

Joseph Stiglitz is one of the most well-known economists in America and a winner of the Nobel Prize.

JOSEPH STIGLITZ:

So you’re doing a documentary on the Fed and monetary policy?

JAMES JACOBY:

We are trying to.

JOSEPH STIGLITZ:

OK [laughs].

JAMES JACOBY:

Are we insane?

JOSEPH STIGLITZ:

No, no, no. I think it’s a great idea.

JAMES JACOBY:

Stiglitz told me that while the Fed was doing some good, he had greater concerns at the time.

JOSEPH STIGLITZ:

The main thing I was concerned about was that the way they were trying to revive the economy was a kind of trickle-down economics. The way quantitative easing works is that it’s a lowering of the interest rates. That leads stocks to go up. And so who owns the stocks? It’s the people in the top. Not just the top 10%, 1%, one-tenth of 1%. And so it increases enormously wealth inequality. We had had increasing inequality really since the late ’70s, and this was putting that on steroids. So the immediate objective of saving the banking system was achieved, but the broader objective, which was helping the economy recover quickly in a robust way, in a way with shared prosperity—total failure.

JAMES JACOBY:

What sort of response did you get from folks at the Fed to what you were saying at the time?

JOSEPH STIGLITZ:

“Our mandate is to do what we can to increase employment, to use the tools that we have, and that’s what we’re doing.”

JAMES JACOBY:

Was that even part of the discussion at the time in the boardroom, whether there was any risk of exacerbating wealth inequality?

SARAH BLOOM RASKIN:

There were strands of that, I recall. These kind of costs were considered speculative, because again, the tools hadn’t been used before, so there wasn’t a clear sense as to what the impact would be. There was some discussion of it, but nothing definitive.

JAMES JACOBY:

Some saw wealth inequality as a trade-off.

RICHARD W. FISHER:

There’s nothing that you could really do about it. But it was, in my mind, in my discussion of what I would present at the table, it would be one of the consequences that we just had to be mindful of. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have done what we did.

JAMES JACOBY:

For Andrew Huszar, it was time to walk away from the Fed.

ANDREW HUSZAR:

It was a while ago, but whenever I come back here, it’s a very special feeling.

JAMES JACOBY:

I bet.

You were still working in this building when the second round of quantitative easing happened. What was your reaction to it when that happened?

ANDREW HUSZAR:

I was not surprised by the announcement, but I was incredibly demoralized. What I was seeing outside of the Fed was rising demands from Wall Street that the Fed continue its stimulus—the idea that the sky was going to fall if the Fed didn’t continue to print money and give it to the Wall Street banks. And yet nobody was giving a coherent explanation as to how the Fed showering trillions of dollars onto Wall Street banks was actually directly benefiting the average American. And I’ll tell you why they weren’t talking about it: Because it doesn’t. We did not see the knock-on benefits that we had hoped for the average American, as much as we wanted to.

JAMES JACOBY:

Why is this kind of an emotional issue for you?

ANDREW HUSZAR:

Well, perhaps it’s because I was a true believer of the Fed, and I worried about what this meant in terms of the future, about how much more the Fed would double down, and how addicted Washington and the markets would become to this extraordinary stimulus.

JAMES JACOBY:

The Fed would keep the money flowing under successive rounds of quantitative easing, injecting more than $2 trillion into the financial system. And by 2013, unemployment was continuing to fall, and the Fed saw signs that its policies were having a positive impact on the economy.

Fed Chairman Bernanke signaled that the easy money might start to taper off.

BEN BERNANKE:

If we see continued improvement and we have confidence that that is going to be sustained then we could, in the next few meetings, we could take a step down in our pace of purchases.

MOHAMED A. EL-ERIAN:

I was on the trade floor. I remember Chairman Bernanke saying that he would taper. First we had to figure out “what does taper mean?” And the minute people realized what “taper” meant, which is that the Fed would step back from buying all these securities, and even though the Fed said it’s going to be gradual, it’s going to be measured, the markets had a massive tantrum.

NEWSREADER:

The market selling off after Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said that the central bank could start tapering its economic stimulus measures later this year.

RICHARD W. FISHER:

The markets went into a fit, became dysfunctional. It was known as the “taper tantrum.”

NEWSREADER:

Well, we all know it: When Ben Bernanke talks, and the Federal Reserve speaks, the markets listen. Taper tantrum!

MOHAMED A. EL-ERIAN:

Markets are like little kids. They want candy, and the minute you try to take the candy away, they have a tantrum.

SARAH BLOOM RASKIN:

You have big Wall Street reaction, right? You have extreme volatility where Wall Street says, “Whoa, whoa, no, no! No, unacceptable!” and values plunge. And of course the Fed doesn’t like that. Nobody likes that—that’s a precursor to instability, right? But it put the Fed in a real bind.

MOHAMED A. EL-ERIAN:

And Chairman Bernanke had to go in a conference in Boston and say, “No, no, no, we’re not tapering.”

BEN BERNANKE:

You can only conclude that highly accommodative monetary policy for the foreseeable future is what’s needed in the U.S. economy.

JAMES JACOBY:

Bernanke’s successor, Janet Yellen, had better luck the following year. She was able to pause quantitative easing without a tantrum, in part by promising to maintain the Fed’s massive balance sheet of assets it had bought and to keep short-term interest rates low.

JANET YELLEN:

The FOMC reaffirmed its view that the current zero to one-quarter percent target range for the federal funds rate remains appropriate.

JAMES JACOBY:

Low rates spurred companies and individuals to borrow, in record amounts. And the federal government took full advantage of the low interest rates as well, running the national debt up a trillion dollars a year, to new highs.

JEROME POWELL:

Good afternoon, everyone, and welcome.

JAMES JACOBY:

By 2018, the new Fed chair, Jerome Powell, was saying the economy was in a good place, citing historically low unemployment numbers and the fact that concerns about inflation hadn’t materialized.

JEROME POWELL:

The U.S. economy is in a good place, and we will continue to use our monetary policy tools to help keep it there.

JAMES JACOBY:

There was a growing debate about whether the Fed should raise interest rates and slow the flow of easy money.

For those who were saying, during that period of time, “You should’ve been concerned about other side-effects of keeping rates so low,” tell me what the downside of raising rates would’ve been.

NEEL KASHKARI, Pres. & CEO, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis:

The downside is keeping Americans on the sideline who want to work.

JAMES JACOBY:

I raised these issues with Neel Kashkari, president of the Minneapolis Fed. He’s been outspoken about how the Fed’s policies have helped lower unemployment and improved the economy overall.

NEEL KASHKARI:

The Fed has been on a mission—I’ve been on a mission—to put Americans back to work and help them get their wages up, especially for those lowest-income Americans. And if it has had some effect on Wall Street, to me, the trade-off is well worth it if we can put Americans back to work so that they can put food on the table, they can take care of themselves. That is profoundly beneficial to society.

JAMES JACOBY:

One of the things that we have seen in this country is a widening wealth gap. The question is what role, if any, the Fed has played in widening that wealth gap?

NEEL KASHKARI:

Well, this is a great point, and I’m glad you raised it. Most people who make this argument ignore the fact that for many Americans, they don’t own a house. They don’t own stocks. They don’t have a 401(k). The most valuable asset they have is their job. So by putting people back to work and helping to boost their wages, we are actually making their most valuable asset more valuable.

JAMES JACOBY:

But the critics I spoke to questioned the Fed’s success and pointed to other indicators.

KAREN PETROU, Author, Engine of Inequality:

Wealth was becoming increasingly unevenly shared. In that quote “good place,” the 1% held 32% of the nation’s wealth. And the majority of Americans said they were financially anxious. Forty percent of Americans didn’t have more than a $400 rainy-day fund. Most Americans were tremendously fragile, economically speaking.

JAMES JACOBY:

Karen Petrou is an unlikely critic of the central bank—she spent her career as an adviser to banks and large investors, analyzing how financial policy played out in the real world.

KAREN PETROU:

Despite the quote “record employment,” when you break those numbers down you can see that more people had jobs, and that’s great, but the wages and the growth in the economy remained very tepid and very unequal.

JAMES JACOBY:

When you speak to folks from the Fed about the idea of raising interest rates, they’ll say, “What was the alternative?” And you say what to that?

KAREN PETROU:

I say, “What you were doing wasn’t working.” We’ll never know whether raising rates would have dampened growth. We do know that keeping rates ultra-ultralow didn’t raise growth. It raised markets.

JAMES JACOBY:

Petrou and other critics were concerned that the Fed’s low rates and easy-money policies were fueling troubling trends on Wall Street and in corporate America. One in particular was the amount of corporate borrowing.

FINANCIAL CORRESPONDENT:

Valuations are generally elevated, especially corporate debt.

FINANCIAL CORRESPONDENT:

We have flagged the rise in corporate debt.

FINANCIAL CORRESPONDENT:

We have entirely too much corporate debt out there.

JAMES JACOBY:

Taking advantage of low interest rates, corporations were selling bonds to big investors. I saw numerous studies and reports detailing the extent of the debt and how even marquee companies were so leveraged their credit ratings plummeted.

The Fed had hoped that companies would put all that borrowed money to good use and invest in their workforce and their infrastructure. But in reality it was playing out differently.

NEWSREADER:

Buybacks.

NEWSREADER:

Buying back stock.

NEWSREADER:

Stock buybacks.

NEWSREADER:

Stock buybacks.

JAMES JACOBY:

Companies were often borrowing money to buy back their own stock, making the remaining shares more valuable and the prices higher.

DION RABOUIN, Markets editor, Axios, 2018-21:

As a corporation you realize all that matters is the stock price. So what do we have to do to increase the stock price? And more often that is buying back the stock.

JAMES JACOBY:

Financial reporter Dion Rabouin covered the growing trend.

DION RABOUIN:

So it used to be the Fed would lower interest rates, businesses would then take on more debt, they would use that debt to hire more workers, build more machines and more factories. Now what happens is the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates, businesses use that to go out and borrow more money, but they use that money to buy back stock and invest in technology that will eliminate workers and reduce employee headcounts. They use that money to give the CEO and other corporate officers big bonuses and then eventually issue more debt and buy back more stock. So it’s this endless cycle of things that are designed to increase the stock price rather than improve the actual company.

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR:

GE just authorized a $50 billion stock buyback.

JAMES JACOBY:

The numbers were astounding: more than $6 trillion in corporate buybacks in the decade after the financial crisis.

NEWSREADER 1:

Warren Buffett likes Apple’s buybacks.

NEWSREADER 2:

Well, why wouldn’t he? He’s a shareholder and they’re buying back $100 billion in stock.

SHEILA BAIR, Chair, FDIC, 2006-11:

Buybacks used to—it’s just another example of things that used to be viewed as kind of “ew” just going mainstream.

JAMES JACOBY:

Sheila Bair, a former top banking regulator, was issuing public warnings at the time that the Fed was incentivizing bad behavior on Wall Street despite its best intentions.

SHEILA BAIR:

I can’t fault the companies so much, because this interest rate environment creates very strong economic incentives to do exactly what they’re doing. It’s hard to create a new product. It’s hard to come up with a new idea for a service. It’s hard to build a plant and hire people and run the organization. It’s real easy to issue some debt and pay it out to your shareholders to goose your share price. That’s real easy to do, but it doesn’t create real wealth. It doesn’t create real opportunity. It doesn’t create jobs. It doesn’t improve the labor market. But it’s just another example of how these very low interest rates have really distorted economic activity and frankly been a drag on our economic growth, not a benefit.

JAMES JACOBY:

Corporate buybacks. The elevation of corporate debt. How was that viewed by you and others at the Fed?

NEEL KASHKARI:

Something we pay a lot of attention to. But when companies are buying back their stock, one of the things they’re telling us is, “We don’t have profitable places to invest, and it’s easier for us just to buy back our stock.” That’s concerning in terms of the future of our economy, but that’s not because of the Fed. So we pay attention to it, it really matters, but in my view, we don’t—it’s not something we control.

JAMES JACOBY:

In our conversation, Kashkari was quick to dispute the criticism that the Fed is really just boosting financial markets and helping Wall Street.

There is this idea on Wall Street that the Fed kind of has our back and that because you may have well-intentioned policies that are trying to get everybody to work, there is this side effect, this unintended side effect, of just kind of really helping the rich.

NEEL KASHKARI:

That argument ignores the benefit to the poor. And for sure, if you’re going to ignore the benefit to the poor, then we’re only helping the rich. But of course, that’s an incomplete analysis. When you actually sit down and say, “Well, let’s go through the trade-offs of the choices that the Fed has,” whether it’s interest rates or it’s quantitative easing, it’s not just about Wall Street. It’s not just about asset prices. It’s also about thinking about the men and women in America who are trying to find work and who want to have higher earnings and who deserve higher earnings. If we are benefiting them by helping them find work and helping them have higher wages, I will take that trade-off.

JAMES JACOBY:

There’s an ongoing disagreement among people I spoke to about how much the Fed has been helping Main Street. But what most do agree on is that it’s fueled the massive growth of the financial sector—a “Golden Age” for Wall Street, as some have called it.

Even some of the largest beneficiaries of this trend told me it made them uncomfortable, like legendary investor Jeremy Grantham.

JEREMY GRANTHAM, Co-founder, GMO LLC:

In my career in America, the percentage of GDP that goes to finance has gone from 3 1/2 to 8 1/2 [laughs]. We’re—in a way we’re like a giant bloodsucker and we have more than doubled in size and sucking more than twice the blood out of the rest of the economy. And we do not generate any widgets. We do not generate any real increase in income. We are just a cost.

JAMES JACOBY:

When you say “we,” you mean you and other members of the financial community have been this kind of bloodsucker on the economy? Is that what you’re saying?

JEREMY GRANTHAM:

Yes. Collectively we fulfill a completely necessary service, but what we have done is created layers upon layers of more and more convoluted, expensive financial instruments. And that’s what makes all the profits for the financial industry. It’s taken a lot of ingenuity and salesmanship to make this happen, and a lot of lobbying in Congress, et cetera, et cetera, and we have imposed on the rest of the economy the idea that banking and finance are utterly important at all times. If you do anything wrong to us, the entire economy will collapse in ragged disarray.

JAMES JACOBY:

As finance grew, so did the risks. One concern was what would happen to all those companies that had gone into debt if there was a downturn, and what would happen to the trillions of dollars in corporate bonds that had been sold to investors.

There were also increasing warnings about a key player in all the borrowing going on—little-known and unregulated financial companies that had been flourishing in the easy-money economy, known as shadow banks.

LEV MENAND, Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of NY, 2016-17:

Shadow banks are large financial institutions that don’t have bank charters, so they don’t have a special relationship to the government. They have other financial licenses to conduct other types of financial businesses.

JAMES JACOBY:

Lev Menand, who’d been an economic adviser at the Fed and Treasury Department, said the biggest source of worry about the shadow banks was their lack of a cushion in the event of a downturn.

LEV MENAND:

The core of the problem of the shadow banking system is that it’s extremely fragile. Anybody who is an investor in a shadow bank, who has their money in a shadow bank instead of a real bank, is going to have an incentive to withdraw in the face of any uncertainty. So little economic shocks that cause asset prices to fall have the potential to trigger runs and panics. And so what we’ve done is, by allowing this shadow banking system to develop, is we’ve inserted a source of instability in our entire economic system that doesn’t need to be there and that has the potential of throwing us all off course.

JEROME POWELL:

Let me start by saying that my colleagues and I strongly—

JAMES JACOBY:

That potential instability posed by the shadow banking system was on the Fed’s radar.

REP. JIM HIMES (D-CT):

How are you thinking about potential risk bubbling up in the broader shadow banking system?

JEROME POWELL:

This is a project that the Financial Stability Oversight Council is working on now. And also, the Financial Stability Board globally is looking carefully at leveraged lending. And we think it’s something that requires serious monitoring.

JAMES JACOBY:

Despite those concerns, little action was taken by the Fed, other regulators or Congress and the system remained vulnerable to a shock. It would arrive in early 2020.

NEWSREADER:

A preliminary investigation into a mysterious pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan, China, has identified a previously unknown coronavirus—

NEEL KASHKARI:

When the pandemic hit, it was so unlike anything any of us have experienced in our lifetimes. We’d been paying attention to what was happening in China for a few months. I was calling my contacts, global businesses that had big operations in China, to understand what their employees and staffs were seeing. And we were all trying to learn as much as we can about pandemics and what it’s likely going to mean.

NEWSREADER:

Major sell-off across Europe this morning.

NEEL KASHKARI:

I think we all figured out very quickly the pandemic and the virus would drive the economy.

NEWSREADER:

Investors are spooked by the growing number of infections outside China.

NEEL KASHKARI:

But how fast would it hit us? How widespread? What would the health care response be? It was maximum uncertainty. And you were seeing that uncertainty manifest in financial markets.

NEWSREADER:

What you have here are concerns, fears, worries and deep uncertainties about what’s likely to happen next.

NEEL KASHKARI:

People were scared. Investors were scared. Individuals were scared. And they said, “You know what? I just want cash.”

NEWSREADER:

Markets giving us the worst two-day point drop ever in history.

NEEL KASHKARI:

“I don’t even want Treasury bonds. I don’t even want corporate bonds. I don’t want stocks. I just want cash.” And when everybody in the economy says “I want cash” at the same time, that leads to potentially a collapse of financial markets.

STOCK MARKET FLOOR TRADER:

On the bell, on the bell!

FINANCIAL REPORTER 1:

The first circuit breaker has been triggered.

FINANCIAL REPORTER 2:

For whom the bell tolls.

MOHAMED A. EL-ERIAN:

Market functioning was starting to cascade into failure.

NEWSREADER:

The Dow plunging again today. The 11-year bull market has ended.

DION RABOUIN:

Stocks were just on a downward free fall. You had credit markets seizing up. People were selling anything that wasn’t nailed down.

NEWSREADER:

Investors are really growing incredibly pessimistic.

NEWSREADER:

The U.S. economy, the biggest economy in the world, is in free fall.

MOHAMED A. EL-ERIAN:

Then comes the realization that we have to lock down.

NEWSREADER:

The list of closings and activities being suspended is growing from coast to coast.

JAMES JACOBY:

COVID had hit the global economy hard and fast, but it wasn’t just the pandemic that was causing a financial crisis. It was the vulnerabilities of a now highly leveraged financial system. Attention focused on the shadow banks.

LEV MENAND:

What we saw in March of last year was a full-blown panic in the shadow banking system. It wasn’t something that you have when you have a pandemic, you have a bank panic. It was you have a bank panic because you had some exogenous shock in the economy and you have these underlying vulnerabilities in your monetary system that you haven’t resolved.

JAMES JACOBY:

The Fed sprang into action. They turned back to quantitative easing, buying hundreds of billions in debt from financial institutions. By mid-March they made more than a trillion dollars available to the shadow banks and they cut interest rates back down to near zero.

NEWSREADER:

The Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near zero—

FINANCIAL REPORTER:

What that tells all of us is that the economic impact of the coronavirus is going to be crippling.

LEV MENAND:

The Federal Reserve lent half a trillion dollars to securities dealers, half a trillion dollars to foreign central banks, bought $2 trillion of Treasury securities, another trillion dollars of mortgage-backed securities. It flooded the zone with new government cash to stabilize this system.

JAMES JACOBY:

But it wasn’t enough to stop the panic.

NEWSREADER:

—as the emergency rate cut failed to calm investors. In fact, it did the opposite. Futures—

JAMES JACOBY:

The corporate debt market had frozen up and companies were unable to finance themselves, putting the wider financial system at risk.

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR:

There’s just this corporate debt picture out there, and we’re just beginning to see how those dominoes are going to fall.

JAMES JACOBY:

So on March 23, the Fed took its economic experimentation to a whole new level. With Congress’ backing, Fed Chair Powell announced a range of new loan programs. He said the Fed for the first time would be willing to buy up corporate debt.

NEWSREADER:

We often talk about the Federal Reserve using a bazooka to tackle markets and the economy. This is bazooka, cannons and tanks all at once.

DION RABOUIN:

So this was huge. This was the Fed stepping in on an unprecedented scale and saying to the market, “We will do whatever it takes.”

REP. ANTHONY BROWN (D-MD):

The motion is adopted.

JAMES JACOBY:

By the end of March, Congress would also act, passing the largest economic stimulus bill ever: the $2.2 trillion CARES Act.

NEWSREADER:

The bill rushed to the president after clearing the House in a voice vote.

JAMES JACOBY:

It provided support for individuals and small businesses.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP:

Good. I wanted that to be a nice signature.

JAMES JACOBY:

A big portion of the bill—nearly half a trillion dollars—was earmarked to support the Fed’s lending programs.

I don’t think most people are aware that we came this close to a bona fide financial crisis.

LEV MENAND:

Yeah. I think a lot of it is missed for two reasons. One, there was a lot of other stuff going on in the news at the time. The other is the Federal Reserve did an amazingly good job at putting out the flames of this panic. And even though the panic in March 2020 was more severe along many metrics than anything we saw in 2008, the government’s response was more powerful in certain respects. And we’re lucky that the government was successful or we could be living through a true depression.

NEWSREADER:

And there’s the opening bell. Looks like markets are set to rally. Part of the reason—

JAMES JACOBY:

But in trying to keep workers employed and companies afloat, the Fed had also used its power to rescue some of the riskiest parts of the financial system, like the junk bond market.

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR 1:

Is this just like a high-yield junk bond bailout? I mean, I don’t get—

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR 2:

Yeah, we’ve got to live with it now, Tom.

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR 1:

—why this is an emergency.

FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR 2:

We’ve got to live with it.

JAMES JACOBY:

To the critics, the Fed was sending the wrong message, rewarding the wrong people.

JEREMY GRANTHAM:

Over the years, we’ve been trained to believe that the Fed is on our side. What the Fed has trained us to believe is that if we make a bet in the market and we win, we’re on our own. We get to keep the profits. If we lose, they will bend every effort and every dollar they can get their hands on, one way or another, to bail us out. This is asymmetry of the most splendid kind.

MALE VOICE:

A speeds. Go ahead and clap it off, please.

JAMES JACOBY:

Billionaire bond investor Howard Marks called the Fed out at the time, saying it was undercutting the way the free market is supposed to work.

HOWARD MARKS, Co-chairman, Oaktree Capital Mgt.:

There are negative ramifications to this. One called moral hazard, which means conditioning people to believe that if there’s a problem the government will bail you out. And if people really believe that, then there’s no downside to risky behavior, because if there’s a problem, it won’t fall on you. You’ll get bailed out. If you play it aggressively and succeed, you make money. If you play it aggressively and fail, you’ll get bailed out.

JAMES JACOBY:

So has moral hazard gotten worse as a result of this bailout?

HOWARD MARKS:

There’s no barometer of moral hazard, so I can’t give you a reading. All I can say is that for the last year or so, risk-taking has been rewarded, and that tends to bring on more risk-taking.

JAMES JACOBY:

Do you see moral hazard in what has just happened?

SHEILA BAIR:

Oh, absolutely. I think now the entire business community has had a taste of bailouts [laughs]. And boy, doesn’t it work really, really nicely. So I fear that now, the Fed stepping in, not just to bail out Wall Street, but the entire corporate America, is starting to be embedded into people’s thinking.

People talk about the survival of capitalism, but this is the biggest threat to capitalism. In good times, when anybody can make money, you reap those profits. In bad times, the Fed just keeps stepping in. You have this never-ending ratchet up. The markets never correct.

JAMES JACOBY:

It’s like a no-lose casino.

SHEILA BAIR:

It is. It is a no-lose casino. That’s exactly right.

JAMES JACOBY:

This is the second time in 12 years that you and your institution have had to funnel into the financial system trillions of dollars, and there is this sense that the financial markets have an iron-clad backstop from the Fed.

NEEL KASHKARI:

Well, I completely agree that it is unacceptable that 12 years after 2008, we had to do this again. I am proud that we did what we did. It was the right thing to do. It was necessary. But it is unacceptable as an American citizen that we have a financial system that is this risky and this vulnerable.

JAMES JACOBY:

But what, if any, responsibility or accountability does the Fed have for the financial system having been so risky and so vulnerable to a shock?

NEEL KASHKARI:

Well, I think all financial regulators that have a seat at the table have responsibility for what was left incomplete after 2008 and where we go from here. We need to use this crisis to finish the work that we did not finish after ’08.

JAMES JACOBY:

With all due respect, I wonder if you could be a little bit more explicit with me. What will the Fed own when it comes to the vulnerability of the system?

NEEL KASHKARI:

Well, I reject the thesis. I actually don’t think it’s been the Fed’s monetary policy that has led to these vulnerabilities. I think it’s been incomplete regulatory policy that has led to these vulnerabilities.

JAMES JACOBY:

That’s an idea Kashkari expressed repeatedly to me: that there are other actors responsible and larger economic forces at play beyond the Fed’s decisions.

NEWSREADER:

The shadow of the pandemic is going to be extremely long. People who lost their jobs—

JAMES JACOBY:

With unemployment still high, the Fed and Congress have continued to pump money into the economy—

UNEMPLOYMENT VOLUNTEER:

Let’s keep ’em coming this way.

JAMES JACOBY:

—trillions to struggling individuals and small businesses. And once again, quantitative easing to keep interest rates low and the cost of borrowing down.

PETER R. FISHER, Federal Reserve Bank of NY, 1985-2001:

Last March, the Fed announced that they’ve just decided it’s gong to be the right thing to do to drive a hundred miles an hour. OK, your judgment call. A year later, they’re still driving a hundred miles an hour. And you ask them, “Why exactly are you driving a hundred miles an hour now?” “Well, it was a good idea last March, and we don’t want to change things too quickly, and so, yeah, we just think it’s a really good idea.”

JAMES JACOBY:

Peter Fisher spent years at the New York Federal Reserve and at BlackRock, the largest asset management firm in the world.

PETER R. FISHER:

It’s pretty basic in medicine that our doctor may give us a drug which in a small, punchy dose, for a brief period of time, might help us recover from whatever ails us, but that the same medicine, the same drug, taken in massive doses over long periods of time might kill us or make us ill or have perverse side effects.

JAMES JACOBY:

Corporate America has taken on even more debt, and investors are gobbling it up. The housing market and the millions of people who own some stocks and bonds are seeing a boom.

NEWSREADER:

Elon Musk has added over 10 billion to his wealth just this week!

JAMES JACOBY:

And for the richest Americans, it’s been a bonanza.

DION RABOUIN:

Just the billionaires in the United States, from March 2020 to February 2021, have grown their wealth by $1.3 trillion. One point three trillion dollars.

FINANCIAL CORRESPONDENT:

Billionaires now hold two-thirds more in wealth than the bottom half of the U.S. population.

DION RABOUIN:

The thing about wealth is, what creates wealth is wealth. When you have a hundred million dollars to invest, it’s much more easy to become a billionaire than when you have a hundred dollars to invest.

ROBINHOOD COMMERCIAL:

You ever think about trading stocks?

JAMES JACOBY:

But that hasn’t stopped many hundred-dollar investors from trying to get a piece of the action.

ROBINHOOD COMMERCIAL:

People like us can trade just like the big guys. With Robinhood.

DION RABOUIN:

All these brokerage platforms saw the largest growth of new users they’d ever seen because people said, “Now is my opportunity. I’m going to invest my money in the stock market. I may not understand what the Fed’s doing or how it works or what exactly is going on—”

NEWSREADER:

—the Dow rising nearly 18%, its best performance since 1987.

DION RABOUIN:

“—but I understand the Fed takes action, stock prices go up, these people get rich.” And it became a very clear mandate for people: “If I want to get in on this economic recovery we’re having, I’ve got to buy stocks.”

YOUTUBE VIDEO:

I’m going to take my stimulus check and I’m going to put it in the stock market.

DION RABOUIN:

So they’re online, they’re trading stocks, they’re buying and selling and putting money into these stock accounts. They started creating their own community.

ROARING KITTY, Social media personality:

Welcome, Declan, Michael Lee—ah, so many people. Bob Smith—

JAMES JACOBY:

Jerome Powell has become a kind of cult figure, master of the money printer—

REDDIT MEME VIDEO:

Money printer go BRRR.

TIKTOK VIDEO:

Invest in these four tickers. I’ll put them right above.

JAMES JACOBY:

Billions have been piling into so-called meme stocks—

ROARING KITTY:

This GameStop situation, we will never encounter a setup like this again.

JAMES JACOBY:

—new financial assets like NFTs—nonfungible tokens—

NEWSREADER:

From art to music to sports, it’s a new phenomenon that is moving quickly and with big numbers.

JAMES JACOBY:

—and cryptocurrencies.

NEWSREADER:

Bitcoin has been on a wild ride during the past few months.

DION RABOUIN:

It doesn’t really matter if something is a good buy or if it’s fundamentally sound.

MIKE WINKELMANN, Digital artist Beeple:

The money is crazy and awesome and I think it’s—

DION RABOUIN:

There’s been so much money injected into the economy that people just need things to buy.

JAMES JACOBY:

I mean, what you’re describing is mania.

DION RABOUIN:

[laughs] Yeah, you could call it mania. Certainly we are in a mania because, again, the Fed has put a floor underneath asset prices. There’s only one direction that things can go, and that’s up. Otherwise, the Fed will step in and act. So if things can only go up, why wouldn’t you just buy?

PETER R. FISHER:

When I look out at what’s been going on the last six months, I see financial mania. I don’t know what the right value of some companies is. But when they change by 50% in six months, I think we should all recognize, boy, that’s hard to estimate the value of that. If it’s 50% higher now than it was six months ago, I guess we were pretty bad on estimating its value six months ago.

JAMES JACOBY:

I assume you’re somebody who has assets, who’s invested, and that this has been a good period for someone like you, in part because you own assets.

PETER R. FISHER:

The Fed, having pumped asset prices to historically high levels, doesn’t make me feel comfortable. I’ll be—I feel as anxious today as I’ve ever felt about the financial world because of my belief that the Fed has been pumping up asset prices in a way that is creating a bit of an illusion. I think the odds are now sort of one in three—very high—that we will look at this as an epic mistake and one of the great financial calamities of all time.

JEREMY GRANTHAM:

They have the housing market, the stock market and the bond market all overpriced at the same time, and they will not be able to prevent, sooner or later, the asset prices coming back down. So we are playing with fire because we have the three great asset classes moving into bubble territory simultaneously.

JAMES JACOBY:

There’s a growing conversation right now about the Fed’s role, about whether it’s driving wealth inequality, whether it’s driving asset prices into dangerous territory that could pop right in our faces and whether the financial system can withstand that. There are these seemingly legitimate questions about being in what seems to be uncharted territory.

NEEL KASHKARI:

These questions come from people who are keen Wall Street observers or Wall Street. I never have once heard this line of questioning from a member of Congress that represents a low-income or minority district. Never once. They come to us and they say, “Why can’t you do more?” They never say, “Oh, my gosh, you’re just benefiting Wall Street. Raise interest rates, because I want to keep Wall Street in check.” They say, “Help my constituents find work.”

So that’s why I find these questions amusing, because I hear them all the time from Wall Street. And these are folks who don’t care about what’s actually happening on Main Street. I don’t hear it from Main Street. I certainly don’t hear it from low-income communities. And I’ve heard all of these questions before.

REPORTER:

The price of virtually everything seems to be going up.

NEWSREADER:

—from used cars to plane tickets to furniture.

REP. KEVIN McCARTHY, House Minority Leader (R-CA):

If you go to get in your car and drive to work, your gas costs more.

JAMES JACOBY:

There are now signs of inflation percolating through the economy.

NEWSREADER:

Annual inflation is expected to top 3 1/2% in the fourth quarter, so now there’s speculation the Fed may speed up its interest rate plans.

JAMES JACOBY:

The Fed insists it’s temporary but has signaled it may taper quantitative easing and raise interest rates as early as 2023.

NEWSREADER:

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said while the economy has rebounded, the job market is still hurting.

NEWSREADER:

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell announced that tweaks to monetary policy may still be needed.

RICHARD W. FISHER:

It is an awfully daunting task. I pray for Jay Powell, and I pray for the committee. Doing this successfully will be a heck of a hat trick.

SARAH BLOOM RASKIN:

I would imagine people at the Fed are scratching their heads about how they are going to be able to get that faucet calibrated to a lower level when necessary.

JAMES JACOBY:

And the risk of them turning off the valve right now is what?

SARAH BLOOM RASKIN:

The risk of turning the valve off is economic collapse, right? You would see asset values actually drop through the floor and a complete lack of confidence. The Fed, by the way, would not, I can’t imagine, turn it off in one move. But when the Fed does move, it’s going to want to do it probably quite gradually, and the question is, will they be able to do it in such a way that doesn’t create this massive economic dislocation?

JAMES JACOBY:

Whatever the Fed does next, the consequences will affect us all.