Issue of the Week: Human Rights

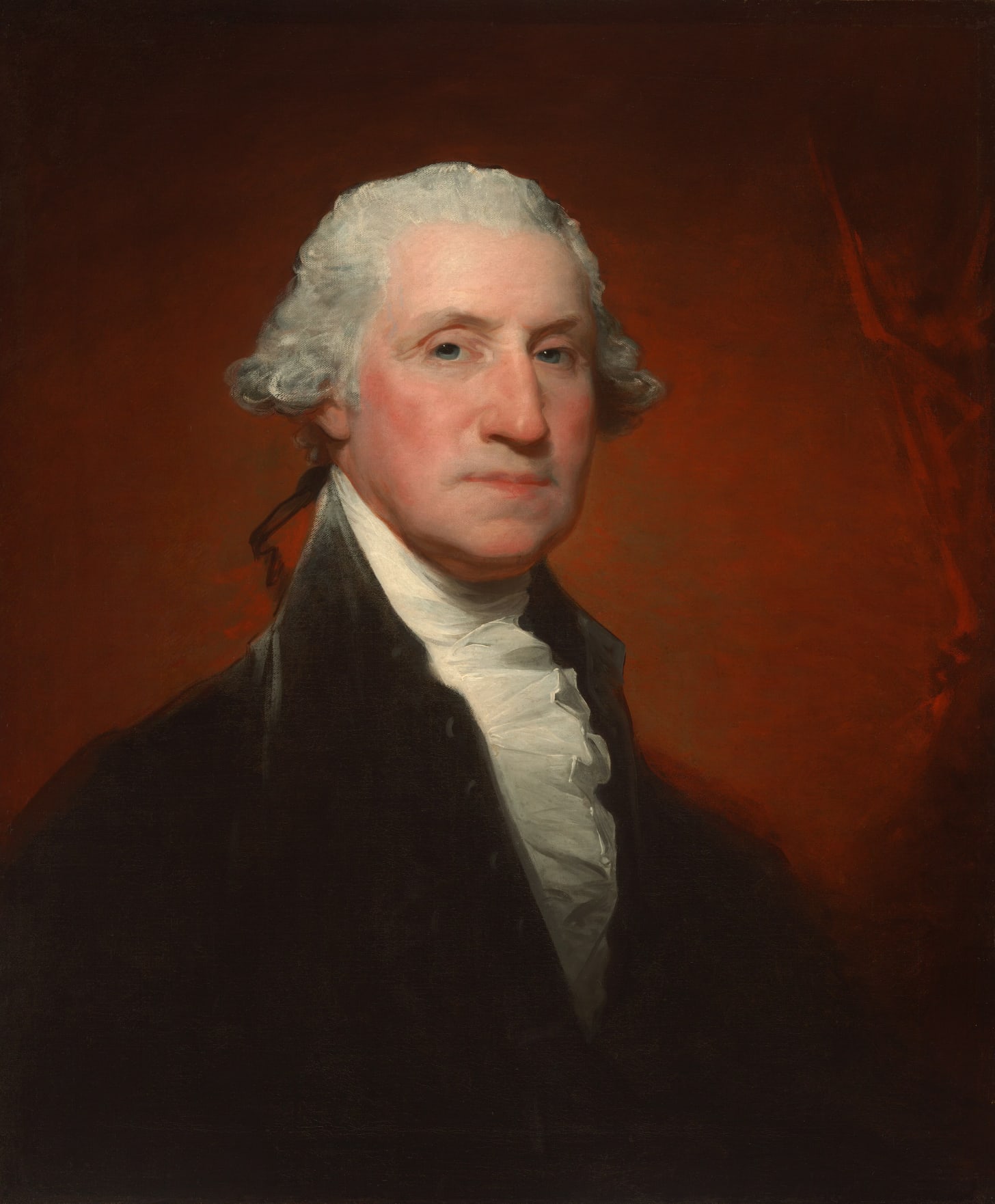

John Trumbull, General George Washington Resigning His Commission (1824) United States Capitol

The New York Times features an article today, on the President’s Day holiday in the U.S., about a new unique project, In Pursuit, to honor the 250th anniversary of American independence.

It was launched today.

To begin with, it will focus on essays on presidents of the U.S.

The first, released today, is by former President George W. Bush on George Washington.

“Few qualities have inspired me more than Washington’s humility,” former President George W. Bush writes in the essay, released as part of a new nonpartisan history project.

Its non-partisan range is impressive.

Starting with Bush is a masterstroke in some ways. Polarization around him went from heroic on 9/11 to foolish at best in Iraq–yet he looks the picture of moderation today. He had already been moving in that direction before Trump, with his deep friendship with Michelle Obama; Barack Obama, running against the war, ending up agreeing with Bush on the surge in Iraq in a 2008 debate (because it was working); reassesments since that the opinions and welfare of younger Iraqis about the war were more multi-dimensional than predicted and that measuring national security strictly in Machiavelian self-interest served neither morality nor self-interest. Many mistakes were made but the whole story is a much longer and still unfolding one. Events since have gobsmacked: Recently deceased former Vice President Dick Cheney, perhaps chief promoter of Iraq intervention, came out full-throated supporting Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris against Donald Trump because of his attempts to dismantle American democracy.

Most recently to the point, and most impactful in the legacy of Bush, were his and Obama’s joining USAID workers on the last day of the dismantling of the agency a few months ago, in tears, saying thank you.

The creation of PEPFAR (The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief is the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease) by Bush (kept in place by Obama, Trump’s 1st administration and Biden, until gutted by Trump’s hatchet man Musk last year to save a pittance while increasing tax cuts in the trillions for himelf and fellow billionaires), in case anyone needs reminding, saved milions of lives from AIDS mainly in Africa, set the course for eliminating this plague, lifted America’s credibility throughout the continent and the world, was mainly funded through USAID, was promised to be in the main left in place after Bush pleaded for this–and wasn’t in many respects. The BBC World Service just aired the most wrenching report yet on the results, babies with lesions and skin falling off and screaming while dying who a few months before would have been treated with anti-viral drugs and saved at clinics minutes away funded by PEPFAR. Meanwhile, infections are increasing again, and back to the global march of the plague we go.

Bush, winner of two consecutive terms of the presidency (the first contested, the second soundly) was a conservative Republican and still is, if becoming more moderate over time, who is one of many who the party of Ronald Reagan would no longer recognize, any more than Reagan would be by his own party.

The point here is not to evade the reality we are in and to set the stage for the man who released the first essay today in the In Pursuit series.

The series features commentators to the right and the left of Bush.

The New York Times reports:

In Pursuit will post new offerings weekly. They will include chronological essays on each American president up to Barack Obama (and some first ladies) by a bipartisan mix of prominent public figures and scholars, including three former presidents and seven Pulitzer-winning historians.

Future installments will include Mr. Obama on Abraham Lincoln, Bill Clinton on Theodore Roosevelt, the Fox News host Bret Baier on Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. on William Howard Taft, the only person to have served both as president and a Supreme Court justice.

Here’s the article, then the essay by former President George Bush on President George Washington.

From One President to Another, a Love Letter With an Edge

To open a series of essays about U.S. presidents, George W. Bush pays tribute to George Washington, who “ensured America wouldn’t become a monarchy, or worse.”

Listen to this article · 7:13 min Learn more

Feb. 16, 2026

For American politicians, there is nothing more uncontroversial than a Presidents’ Day tribute to George Washington, the upright Virginian who may (or may not) have chopped down that cherry tree but otherwise stands as the embodiment of leadership and virtue.

But in an essay published on Monday, a more recent George W. is putting a little 2026 edge on the subject.

“Few qualities have inspired me more than Washington’s humility,” former President George W. Bush writes in the essay, which was released as part of a new nonpartisan history project.

“Our first president could have remained all-powerful, but twice he chose not to,” Mr. Bush writes, referring to Washington’s decision to relinquish leadership of the Army after the American Revolution, and then to step down from the presidency after two terms.

By “relinquishing power rather than holding onto it,” Mr. Bush continues, “he ensured America wouldn’t become a monarchy, or worse.”

These days, as Americans debate the fractured state of our democracy — and the actions of the current occupant of the Oval Office — that simple statement might seem long on subtext, or even shade.

Mr. Bush is not giving interviews. And Colleen Shogan, the leader of In Pursuit, the new history project, said the essay speaks for itself. “His ideas are his ideas,” she said.

The goal of the essay series, Dr. Shogan said, is to make history “relevant” while not speaking narrowly to the specifics of the present.

“We are taking the long view of things,” she said. “The lesson of presidential humility transcends time.”

In Pursuit, created for this year’s 250th anniversary of American independence, will post new offerings weekly on Substack. They will include chronological essays on each American president up to Barack Obama (and some first ladies) by a bipartisan mix of prominent public figures and scholars, including three former presidents and seven Pulitzer-winning historians.

Future installments will include Mr. Obama on Abraham Lincoln, Bill Clinton on Theodore Roosevelt, the Fox News host Bret Baier on Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. on William Howard Taft, the only person to have served both as president and a Supreme Court justice.

For all of the project’s bipartisan bona fides, it is landing at a hyperpolarized moment when the already battered ideal of nonpartisan history is feeling additional strain.

Last fall, groups aligned with President Trump formed a new civics coalition to promote his Make America Great Again agenda, separate from the numerous cross-partisan efforts already out there. And for the 250th commemoration, Mr. Trump has created a new entity, Freedom 250, to organize efforts like a mobile “Freedom Truck” history exhibit that is touring the country and a planned U.F.C. fight on the White House lawn.

Doing nonpartisan history in today’s climate, Dr. Shogan acknowledged, “is not a walk in the park.” Last year, she was abruptly fired by Mr. Trump from her position as head of the National Archives.

There will not be essays about or contributions from Mr. Trump or Joseph R. Biden Jr., which avoids some minefields. But the roster does include two other cultural leaders who, like Dr. Shogan, have come under attack by the Trump administration: Lonnie G. Bunch III, the secretary of the Smithsonian, and Carla D. Hayden, the former librarian of Congress, who was fired last year because of her support for diversity initiatives.

Asked if she was concerned that In Pursuit would be dismissed as partisan, Dr. Shogan pointed to the fact that it is supported by More Perfect, a broad civics coalition including 43 presidential centers, from Washington’s Mount Vernon to the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago.

“But ultimately,” she said, “the project will have to stand on its own merits.”

Each contributor was given a tight 1,250 words (former presidents, Dr. Shogan quipped, “get an extra 100 words”) and one basic prompt: Create a “lesson” and then orient the essay around it. Mr. Bush’s is “For a leader, humility is the ultimate strength.”

Mr. Bush, who also recorded an audio version of his essay, does not shy away from the less attractive sides of his subject. He notes Washington’s limitations as a battlefield commander, and addresses Washington’s entanglements with slavery, a subject that the Trump administration has sought to suppress.

“He was — as were so many of his generation — a lifelong slave owner who never publicly condemned the institution,” Mr. Bush writes. Washington’s private views “evolved over time,” and in his will he did free the enslaved people he owned — the only major founder to do so.

“Still,” Mr. Bush writes, “slavery is a stain on an otherwise sterling private and public life.”

In Pursuit favors textured reflection over the hard math of presidential rankings. But the who’s up, who’s down approach remains a popular parlor game.

Last month, the conservative media platform PragerU unveiled its first presidential rankings, which it described as drawing on “voices and views that are often ignored.” (Among those polled were Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth; the media personalities Glenn Beck and Bill O’Reilly; and Newt Gingrich, the former speaker of the House.)

Washington (surprise!) is ranked first, followed by Lincoln, Ronald Reagan and Calvin Coolidge, a tariff-loving big-business conservative who is described as “the best president you don’t know.”

The PragerU rankings do not include President Trump, on the grounds that his presidency is not yet over. But Mr. Biden finishes dead last, behind Andrew Johnson and James Buchanan. Johnson and Buchanan finish at the bottom of most surveys. And In Pursuit, Dr. Shogan said, will deal frankly with their failures.

But the project’s early installments, which were shared with The New York Times, tend to focus on the ways the founding generation laid down precedents and norms as they figured out how the ideal of democratic self-government would actually work.

Writing about John Adams, the Harvard scholar Danielle Allen extols his willingness to elevate other leaders and defer to their expertise. (An 18th-century equivalent of the mantra “personnel is policy?”)

In an essay about Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Davenport, a historian who leads the research division at Monticello, highlights his “faith in the future,” which rested on his belief in the wisdom of an educated citizenry.

And the first ladies? Those essays, starting with a consideration of Martha Washington by the historian Karin Wulf, aim to transcend gowns and gossip and explore the ways these women did not just invent a role but shaped American political life.

It is easy to love Abigail Adams, who urged her husband to “remember the ladies,” and warned that women would “foment a rebellion” if he and other male founders did not. But the series, Dr. Shogan promised, will also include some sleepers.

Two words: Sarah Polk.

“I think that essay is really going to surprise people,” Dr. Shogan said.

Jennifer Schuessler is a reporter for the Culture section of The Times who covers intellectual life and the world of ideas.

. . .

In Pursuit

A national project to debrief the America experiment at 250 years. In Pursuit is a non-partisan, not-for-profit initiative of More Perfect.

George Washington by George W. Bush

For a Leader, Humility Is the Ultimate Strength

FEB 16, 2026

As America begins to celebrate our 250th anniversary, I’m pleased to have been asked to write about George Washington’s leadership. As president, I found great comfort and inspiration in reading about my predecessors and the qualities they embodied. Abraham Lincoln’s resolve, Harry Truman’s decisiveness, Ronald Reagan’s optimism, and others reminded me of the challenges America has faced – and of the values that have helped us overcome them.

Few qualities have inspired me more than Washington’s humility. I have studied the corrupting nature of power, and how retaining power for power’s sake has infected politics for generations. Our first president could have remained all-powerful, but twice he chose not to. In so doing, he set a standard for all presidents to live up to. His life, with all its flaws and achievements, should be studied by all who aspire to leadership. George Washington’s humility in giving up power willingly remains among the most consequential decisions and important examples in American politics.

After leading the United States to victory over Great Britain in the Revolutionary War, George Washington was at the height of his power. Some suggested that he should become king. Instead, General Washington resigned his military commission in 1783. When King George III of Great Britain learned of his vanquisher’s intentions, he reportedly said, “If He did, He will be the greatest man in the world.” What Washington did on that cold December afternoon in Annapolis shaped the foundation and future of American democracy. And he was just getting started.

Washington’s path to greatness wasn’t always easy. His father died when he was 11. Rather than receiving a classical education in London like his older half-brothers, young George had to help his mother on Ferry Farm, where he learned the value of hard work. His father’s death and his own lack of education bred an insecurity. That insecurity, in turn, led to an insatiable hunger for knowledge. Largely self-taught, he became a voracious reader.

As a boy, he schooled himself in the “gentlemanly arts” by copying the 110 maxims from Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation, which shaped his character for the rest of his life. Many of the qualities that came to be associated with Washington’s leadership, from self-control and courteousness to modesty and diplomacy, can be traced to that short book on manners.

When he was 20, Washington’s interests shifted from the field of surveying to the field of battle. He started his military career as a young officer in the Virginia militia. During a single battle in the French and Indian War, four musket balls ripped through his coat, and his horse was shot out from under him. He never received a commission in the British army.

As the American commander of the Continental Army for more than eight years, Washington’s humility led him to listen, a very different style from British leadership. As Washington wrote to Major General Stirling, “a people unused to restraint must be led, they will not be drove.” Washington listened and learned not just from top military brass but from his soldiers down the ranks, in one case asking their advice on where to advance next after crossing the Delaware River and taking Trenton, New Jersey.

Subsequent leaders learned from that lesson, including Abraham Lincoln, who made sure to listen to privates as much as generals. Despite commanding badly outmanned soldiers and losing more battles than he won, America under Washington’s leadership emerged victorious in a war that changed the trajectory of world history. With Washington, character was key – in this case his humility, perseverance despite difficult odds, indomitable will, and the loyalty he inspired in others.

In early 1783, that loyalty would be tested. His men were tired, homesick, and angry about unpaid wages. Their frustration with the Continental Congress was boiling over, and there was talk of mutiny among the officers. On March 15, in a speech to the troops, Washington spoke about their common cause, their duty to each other, and the righteousness of their mission. He also stressed his personal bond with them, refusing to elevate himself above his men.

Before he made history, Washington had studied it. He was especially drawn to Roman leaders and generals wary of power. So like Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, who retired to his farm after saving Rome in battle, Washington returned to Mount Vernon after winning the war. It was the place that centered him, provided him with happiness, and enabled him to spend time with his beloved wife, Martha. But before long, duty once again summoned him.

The young republic was in crisis. The Articles of Confederation were failing, with the federal government virtually powerless. In 1787 Washington was called back to public life, where he presided over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. He was asked to serve because he was a national hero and a unifying figure, trusted by all, and unmatched in his ability to forge consensus. He could be given power because of his character; because everyone knew he would not abuse power.

Out of the Convention emerged a new Constitution and a new office, the presidency. Washington was the obvious choice and twice was unanimously elected – the only president so elected in American history. He accepted the presidency because the office needed him, not because he needed the office.

Our first president stabilized the economy and the nation’s finances, asserted the authority of the federal government, and secured passage of the Bill of Rights. He kept America out of the French Revolutionary wars, successfully put down an insurrection in western Pennsylvania, and assembled and skillfully managed a cabinet of brilliant but contentious individuals. He delivered a foundational message on religious tolerance to the Touro Synagogue in Rhode Island. He signed legislation to create the nation’s court system and first executive departments.

The question we must all ask is, how did he accomplish these things? By most historian accounts, one of the reasons Washington achieved all of this was by admitting he might not be up to the task. He summoned experts and let debates play out in front of him. For me, that lesson meant recognizing what I didn’t know as President, surrounding myself with advisors who did know what I didn’t know, and listening to them.

Like all presidents, Washington had his faults. He made tactical errors, especially early in his military career. He could be prickly and “naturally irritable,” in the words of Thomas Jefferson. But worst of all, he was – as were so many of his generation – a lifelong slave owner who never publicly condemned the institution. His views evolved over time, expressing private misgivings about slavery later in his life. It’s been said he “made his most public antislavery statement after his death” by freeing the slaves he owned in his will, which is more than most people of his generation did. Still, slavery is a stain on an otherwise sterling private and public life.

But Washington, like all of us, should be taken in the totality of his acts and of his life in his times. By that standard, his life was exceptional. The founding generation considered Washington to be the “indispensable” man. Without him, there would be no America; and without America, the world would be a very different and much darker place.

As Doug Bradburn, President and CEO of George Washington’s Mount Vernon, put it, “His perseverance, steadfast optimism, and ultimately his wisdom drew upon a deep integrity and humility, which over many trials created in him the character of the greatest political leader of the revolutionary age.”

As America’s first president, Washington knew “the first of everything in our situationwill serve to establish a precedent.” So after two terms in office, with a distrust of long-seated rulers still fresh on America’s soul, Washington chose not to run again for president. And by once again relinquishing power rather than holding on to it, he ensured America wouldn’t become a monarchy, or worse.

Our first leader helped define not only the character of the presidency but the character of the country. Washington modeled what it means to put the good of the nation over self-interest and selfish ambition. He embodied integrity and modeled why it’s worth aspiring to. And he carried himself with dignity and self-restraint, honoring the office without allowing it to become invested with near-mythical powers.

I often say that the office of the president is more important than the occupant; that the institution of the presidency gives ballast to our ship of state. For that stability we are indebted to the wisdom of our founding fathers’ governing charter and the humility of our nation’s first president. It has guided us for 250 years, and it will strengthen us for our next 250 years.

George W. Bush founded the George W. Bush Presidential Center and served as the 43rd President of the United States.

In Pursuit is a landmark initiative of More Perfect, a bipartisan alliance of 43 Presidential Centers, National Archives Foundation, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Karsh Institute for Democracy at the University of Virginia, and more than 100 organizations working together to protect and renew our democracy as we approach the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and beyond.

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017